Protecting Innovation: Key Intellectual Property Strategies for Startups in Japan

TL;DR

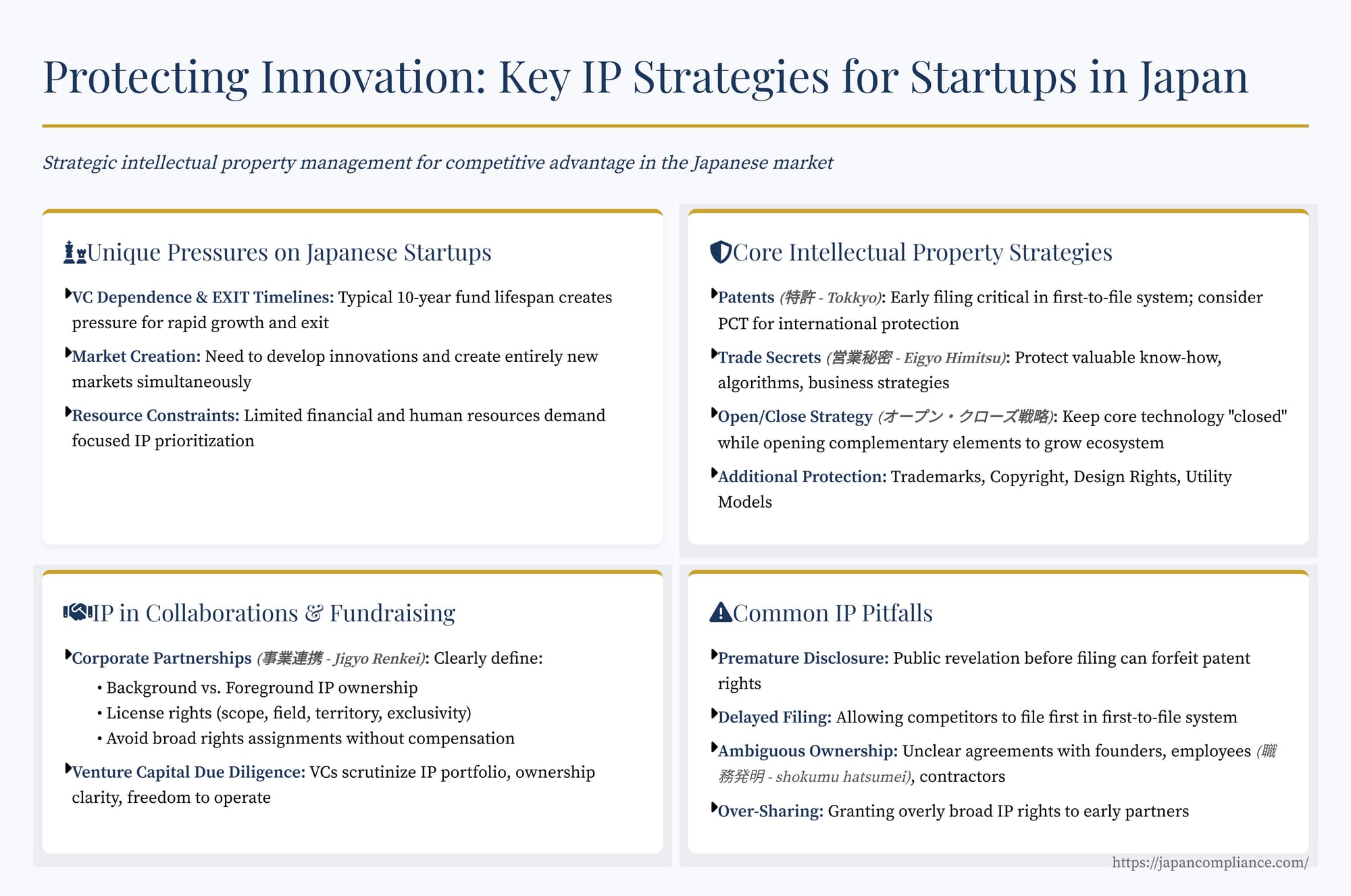

In Japan’s VC-driven startup scene, IP is a core asset. File patents early, manage trade secrets, run freedom-to-operate checks, and use an “open/close” strategy—keep breakthrough tech closed while opening interfaces to build an ecosystem. Negotiate collaboration IP terms carefully and ensure clean ownership for due-diligence. Avoid pitfalls such as premature disclosure or ambiguous inventor assignments.

Table of Contents

- The Unique Pressures Shaping Startup IP Strategy in Japan

- Core Intellectual Property Strategies

- IP in Collaborations and Fundraising

- Common IP Pitfalls for Japanese Startups

- Conclusion

Japan's startup ecosystem is vibrant and increasingly attracting attention from global investors and corporate partners. For many of these emerging companies, particularly those in technology-driven sectors, intellectual property (IP) is far more than a legal checkbox; it's a foundational strategic asset. A well-managed IP portfolio is crucial for securing funding, establishing market differentiation, deterring competitors, enabling collaborations, and ultimately achieving a successful exit (like an IPO or M&A). Understanding the specific nuances of IP strategy within the Japanese startup context is therefore vital for both the startups themselves and the international entities looking to invest in or partner with them.

The Unique Pressures Shaping Startup IP Strategy in Japan

Startups operate under conditions distinct from established corporations, and these factors significantly influence their approach to IP:

- Venture Capital Dependence and EXIT Timelines: Many Japanese startups rely heavily on Venture Capital (VC) funding, often secured through multiple rounds (Series A, B, etc.). VC funds typically have a limited lifespan, often around 10 years in Japan . This creates intense pressure on startups to demonstrate rapid growth and achieve a high-value exit within that timeframe, allowing VCs to return capital to their investors. Strong, defensible IP is a key factor VCs scrutinize during due diligence, as it underpins valuation and future market potential.

- The Need for Rapid Growth and Market Creation: To justify VC investment and reach exit velocity, startups often need to not only develop innovative products or services but also rapidly scale their business and sometimes even create entirely new markets . This dual challenge, undertaken with limited resources compared to incumbents, makes strategic IP management essential for both protecting core innovations and facilitating market growth through partnerships or ecosystem building.

- Resource Constraints: Early-stage startups typically operate with limited financial and human resources. This necessitates a focused and cost-effective IP strategy, prioritizing the protection of genuinely differentiating assets and making smart choices about what to protect, how, and where.

These pressures mean that IP cannot be an afterthought. It must be integrated into the core business strategy from the outset.

Core Intellectual Property Strategies

A robust IP strategy for a Japanese startup typically involves several key components:

1. Identifying and Protecting Core Assets:

The first step is identifying the "crown jewels" – the innovations that provide a sustainable competitive advantage. Protection mechanisms include:

- Patents (特許 - Tokkyo): Essential for protecting technological inventions. Given Japan's first-to-file system, early filing is critical to prevent competitors from patenting similar inventions first. Startups should consider:

- Domestic Filing: Securing rights in Japan.

- International Filing (PCT): Preserving the option for protection in key overseas markets.

- Utility Models (実用新案 - Jitsuyo Shin'an): A potentially faster and less expensive option for protecting simpler inventions or improvements with a shorter protection term (10 years).

- Trade Secrets (営業秘密 - Eigyo Himitsu): Protecting valuable confidential information like know-how, manufacturing processes, algorithms, customer lists, or business strategies that aren't patented. Protection under Japan's Unfair Competition Prevention Act (不正競争防止法 - Fusei Kyoso Boshi Ho) requires demonstrating that the information is kept secret (access controls, NDAs), is useful for business, and is not publicly known. This demands active management and internal controls.

- Trademarks (商標 - Shohyo): Protecting brand names, logos, and service marks is crucial for building brand identity and preventing consumer confusion. Early registration in Japan (and key potential markets) is vital.

- Copyright (著作権 - Chosakuken): Protects original works of authorship, including software code, website content, manuals, marketing materials, and artistic designs. While protection arises automatically upon creation in Japan (as a Berne Convention member), registration with the Agency for Cultural Affairs can offer advantages in enforcement, such as statutory presumptions regarding authorship and date of creation.

- Design Rights (意匠権 - Ishoken): Protects the aesthetic appearance (shape, pattern, color) of a product. Increasingly important for products where visual appeal is a key differentiator.

2. Freedom to Operate (FTO) Analysis:

Before launching a product or making significant investments, startups must assess whether their intended activities might infringe on existing third-party IP rights. Conducting Freedom to Operate (FTO) searches and analysis helps identify potential blocking patents or other rights, allowing the startup to design around them, seek licenses, or challenge the validity of problematic rights. Ignoring FTO can lead to costly litigation, injunctions, and potentially derail the business.

3. Open/Close Strategy (オープン・クローズ戦略):

For startups aiming to build an ecosystem or platform around their technology, a sophisticated "Open/Close Strategy" can be highly effective . This involves:

- Closing Core Technology: Identifying the startup's truly unique and valuable core technology and keeping it "closed" – protected via strong patents and/or rigorous trade secret management. This preserves the core competitive advantage and potential licensing revenue streams.

- Opening Complementary Elements: Strategically making other parts of the technology, such as APIs, interfaces, or certain applications, "open." This can involve publishing specifications, offering royalty-free or RAND (Reasonable and Non-Discriminatory) licenses, or contributing to industry standards .

- Benefits: The "open" elements encourage wider adoption, attract developers and partners, grow the overall market for the core technology, and can create network effects. The "closed" core ensures the startup retains control and a primary monetization path. This strategy requires careful planning to define the boundaries between open and closed elements and ensure the open elements drive value back to the closed core . For example, a successful university spin-out in the advanced materials sector reportedly keeps its core material manufacturing processes secret (closed) while actively patenting and licensing applications and secondary materials derived from it (open) to build an industry ecosystem .

4. Establishing an IP Management System:

Even lean startups need basic internal processes for IP management. This includes:

- Identifying potentially patentable inventions from R&D activities.

- Ensuring clear IP ownership through well-drafted employment agreements (addressing employee inventions) and contracts with external developers or consultants.

- Implementing procedures for handling confidential information to maintain trade secret status.

- Tracking filing deadlines and maintenance fees for registered IP.

- Appointing someone responsible for overseeing IP matters.

IP in Collaborations and Fundraising

IP plays a pivotal role in two critical activities for startups: partnering with established companies and securing investment.

1. Collaborating with Large Corporations (事業連携 - Jigyo Renkei):

Open innovation through partnerships with larger corporations can provide startups with resources, market access, and credibility. However, IP ownership and usage rights are frequent points of friction.

- Negotiating IP Clauses: Joint Development Agreements (共同研究開発契約 - Kyodo Kenkyu Kaihatsu Keiyaku), pilot agreements, and other collaboration contracts must clearly define:

- Ownership of Background IP (existing IP brought by each party).

- Ownership of Foreground IP (IP developed jointly during the collaboration).

- License rights granted between the parties for both background and foreground IP (scope, field of use, territory, duration, exclusivity, sublicensing rights).

- Ownership Models: While joint ownership of patents might seem equitable, it can be cumbersome under Japanese law, as licensing or assignment typically requires the consent of all co-owners . Often, a more practical model is for the startup to retain sole ownership of the foreground IP (especially if it relates to its core technology) and grant the corporate partner appropriate licenses tailored to the collaboration's purpose . This preserves the startup's flexibility for future development and partnerships.

- Fairness and Guidelines: Startups should be wary of corporate partners demanding overly broad rights or outright assignment of foreground IP without fair compensation or clear strategic rationale. Guidelines issued by Japanese government bodies (like METI and the JFTC) emphasize the need for fair negotiations and warn against larger companies leveraging their bargaining power to impose unreasonable IP terms on startups . These guidelines advocate for IP arrangements that maximize the overall value generated by the collaboration. Model contracts provided by agencies like the Japan Patent Office can offer useful starting points .

2. Attracting Venture Capital:

VCs view IP as a critical indicator of a startup's defensibility, scalability, and value. During due diligence, they will scrutinize:

- IP Portfolio: What patents, trademarks, etc., does the startup own or have licensed in? Are they relevant to the core business? Are they geographically appropriate?

- Ownership: Is ownership clearly established? Are there proper assignment agreements from founders, employees, and contractors? Are there any third-party claims or encumbrances?

- Freedom to Operate: Has the startup assessed the risk of infringing third-party IP? Are there known blocking patents?

- Trade Secret Management: Are robust measures in place to protect key confidential information?

- IP Strategy: Does the startup have a coherent plan for how IP supports its business goals?

A weak or poorly managed IP position can be a major obstacle to securing funding or can significantly reduce valuation.

Common IP Pitfalls for Japanese Startups

Startups, often focused on product development and market entry, can sometimes overlook critical IP steps:

- Premature Disclosure: Disclosing an invention publicly (e.g., at conferences, in publications, through product demonstrations) before filing a patent application can destroy novelty and forfeit patent rights. Japan has grace periods, but relying on them is risky and complex, especially for international protection.

- Delayed Filing: Postponing patent or trademark applications due to cost or time constraints can allow competitors to file first.

- Ignoring FTO: Failing to conduct FTO analysis can lead to launching an infringing product, resulting in litigation and market withdrawal.

- Ambiguous Ownership: Not having clear, written agreements transferring IP rights from founders, employees (especially regarding employee inventions - 職務発明, shokumu hatsumei), and contractors to the company can create ownership disputes later.

- Inadequate Trade Secret Protection: Treating valuable know-how casually without implementing confidentiality agreements, access restrictions, and marking documents can result in the loss of trade secret status.

- Over-Sharing in Partnerships: Granting overly broad or exclusive IP licenses to early partners without careful consideration can severely limit the startup's future strategic options.

Conclusion

For innovation-driven startups in Japan, intellectual property is not a peripheral legal concern but a core strategic element woven into the fabric of the business. Proactively identifying valuable IP, securing robust protection through patents, trade secrets, trademarks, and copyrights, conducting FTO analysis, and strategically managing IP rights in collaborations and funding rounds are essential for navigating the path from concept to successful exit. For US companies and investors looking to engage with Japan's dynamic startup landscape, understanding this IP-centric approach and performing thorough IP due diligence are critical steps towards building successful and sustainable ventures.

- Moral Rights in Japan: Protecting Creative Integrity and Attribution in Corporate Communications

- Double Assignment of Claims in Japan: Who Wins and Why?

- Playing a Leading Role? Japan's Antitrust Surcharge Enhancements for Cartel Facilitators

- Startup Support Program – Japan Patent Office (JPO)

- Open Innovation & Intellectual Property Guidelines – METI

- Intellectual Property Strategy Headquarters – Cabinet Office