Yours, Mine, or Ours? A 1961 Japan Supreme Court Ruling on Marital Income, Separate Property, and Constitutional Equality

Date of Judgment: September 6, 1961

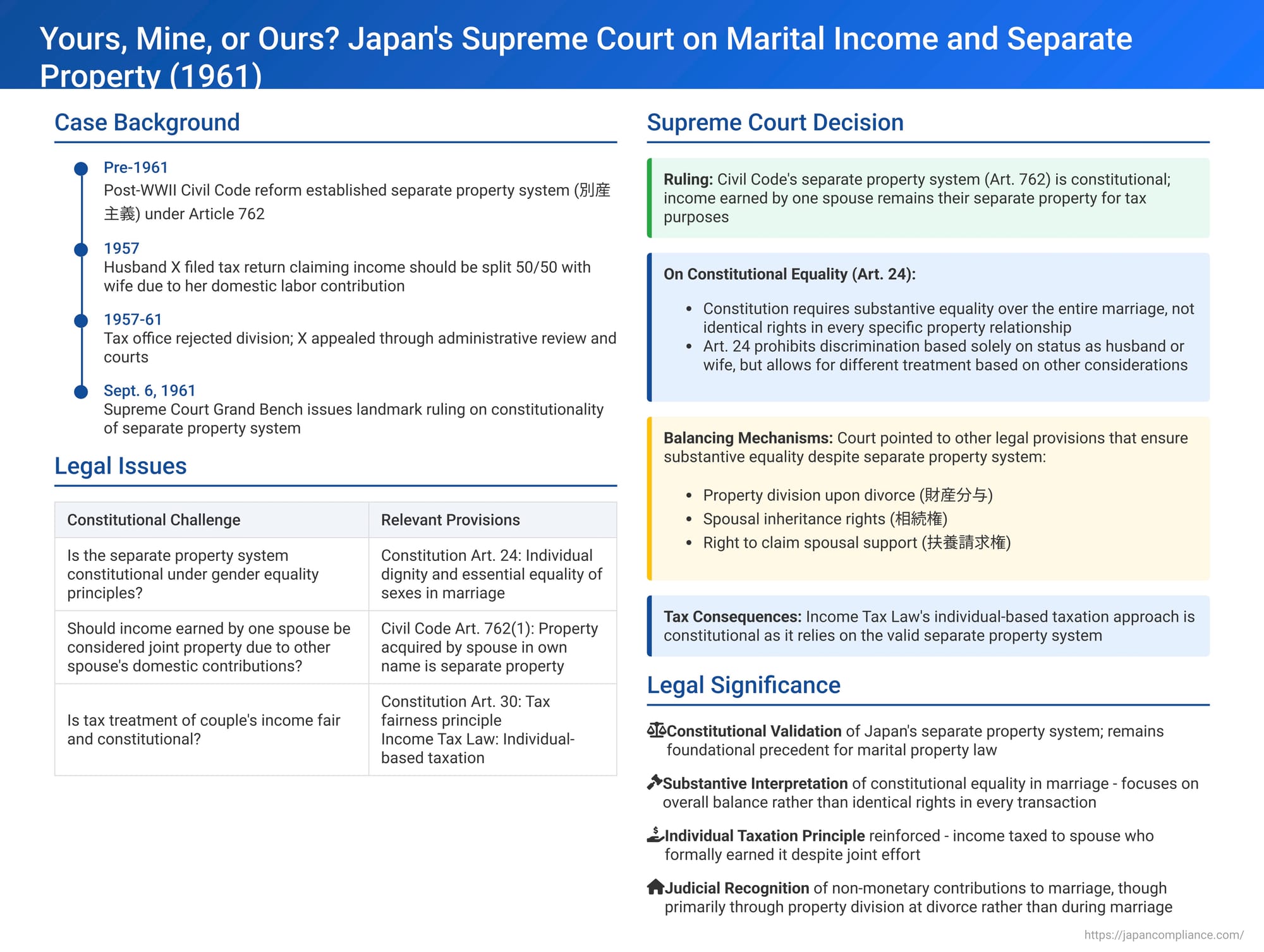

The financial dimension of marriage is a complex area of law, with different legal systems adopting varying approaches to how property acquired during a marriage is owned and managed by spouses. Japan's Civil Code, in Article 762, paragraph 1, establishes what is known as a "separate property system" (別産主義 - bessan shugi). This principle generally dictates that property acquired by one spouse in their own name, even during the marriage, remains their individual, separate property. This system came under constitutional scrutiny in a landmark decision by the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on September 6, 1961 (Showa 34 (O) No. 1193). The case primarily questioned how income earned by one spouse—historically, often the husband—should be treated for income tax purposes, particularly when the other spouse's contributions (such as domestic labor) were seen as integral to earning that income.

The Taxpayer's Challenge: A Plea for Recognizing Joint Spousal Effort

The plaintiff, X (the husband), when filing his income tax return for the year Showa 32 (1957), took an unconventional approach. He declared that his employment income and business income, although legally acquired in his name, were the result of the joint efforts and cooperation of himself and his wife, A. He specifically mentioned A's contributions through her domestic labor as being instrumental in enabling him to earn this income. Consequently, X argued that this income should not be considered solely his but should be equally attributed to both spouses. In his tax filing, he reported only half of this combined employment and business income as his own, presumably with the intent that the other half would be considered A's income. He then added his dividend income to this halved amount to arrive at his declared total taxable income.

The local tax office director, however, did not accept this division. The tax authority reassessed X's income, attributing all the employment and business income originally earned in X's name solely to X. X's subsequent request for a review of this decision by Y, the Director of the Osaka Regional Taxation Bureau, was rejected.

This led X to file a lawsuit seeking the cancellation of the tax authority's decision. His core argument was that the Income Tax Law, by assessing the entirety of the income as his alone, and the underlying Civil Code Article 762(1) establishing the separate property system, were unconstitutional. He contended that these legal provisions violated Article 24 of the Constitution of Japan, which guarantees individual dignity and the essential equality of the sexes in matters pertaining to marriage and the family, and also Article 30, which concerns the duty to pay taxes as provided by law (implying a principle of fairness in taxation). X asserted that both the tax law and the civil code provision ignored the reality that marital income is typically the fruit of joint spousal cooperation.

The first and second instance courts had dismissed X's claim. They reasoned that the Income Tax Law's approach to spousal income was based on the separate property system of Civil Code Article 762(1). They found that this Civil Code provision itself was not in conflict with Constitution Article 24, and therefore, the Income Tax Law relying upon it was also constitutional. X appealed this outcome to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: Separate Property System Upheld as Constitutional

The Grand Bench of the Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby affirming the constitutionality of both Civil Code Article 762(1) and the Income Tax Law's application of the separate property principle.

1. Interpreting Constitutional Equality in Marriage (Constitution Article 24):

The Supreme Court began by interpreting the meaning and scope of Article 24 of the Constitution. It stated that Article 24, which mandates that marriage shall be based on individual dignity and the essential equality of the sexes, aims to ensure that when the marital relationship is viewed as a whole and over its duration, the husband and wife substantively enjoy equal rights. The Court clarified that this constitutional provision prohibits unequal treatment in the enjoyment of rights based merely on one's status as a husband or a wife. However, importantly, the Court found that Article 24 does not demand that spouses must always have identical rights in every specific legal relationship or concerning every individual piece of property. It focuses on overall, substantive equality rather than strict, uniform identity of rights in all particulars.

2. Constitutionality of Civil Code Article 762(1) (The Separate Property System):

The Court then examined Civil Code Article 762(1), which stipulates that property obtained by one spouse in their own name during marriage constitutes their separate property (特有財産 - tokuyū zaisan). The Court noted that this rule applies equally to both the husband and the wife; it is, on its face, formally non-discriminatory.

Addressing X's argument that marital property is acquired through joint spousal cooperation (with the non-earning spouse contributing through domestic labor, etc.), the Supreme Court acknowledged this reality. However, it pointed out that the Civil Code provides other legal mechanisms through which such spousal cooperation and contribution are recognized and substantive equality is ultimately achieved. These mechanisms include:

- The right to claim a distribution of property upon divorce (財産分与請求権 - zaisan bunyo seikyūken) under Article 768: This allows for a division of assets accumulated during the marriage, taking into account each spouse's contributions, including non-monetary ones like housework and childcare.

- Spousal inheritance rights (相続権 - sōzokuken) under Article 890 and related provisions: Upon the death of one spouse, the surviving spouse has significant inheritance rights.

- The right to claim spousal support (扶養請求権 - fuyō seikyūken): During the marriage, and potentially after divorce in some circumstances, spouses have a right to be supported by each other.

The Supreme Court reasoned that through the exercise of these various rights, "legislative consideration is given to ensure that no substantive inequality ultimately arises between spouses due to their mutual cooperation and contributions". Therefore, the Court concluded that Civil Code Article 762(1), when viewed within the broader context of these balancing provisions, does not violate the principles of Constitution Article 24. This judgment explicitly affirmed that Article 762(1) indeed prescribes a separate property system.

3. Constitutionality of the Income Tax Law's Application:

Having established the constitutionality of Civil Code Article 762(1), the Supreme Court then addressed the Income Tax Law. It stated that since the Income Tax Law, in its method of calculating the income of a couple living together, relies on this constitutionally sound separate property system, the Income Tax Law's approach is also not unconstitutional. This meant that, for tax purposes, income would continue to be assessed based on the individual in whose name it was earned.

The "Separate Property System" in Japan: Context and Evolution

Japan's statutory marital property system, primarily governed by Civil Code Article 762, defaults to a separate property regime unless spouses enter into a specific contractual property agreement (which is rare). This means that assets owned by a spouse before marriage, and assets acquired in their own name during marriage, generally remain their individual property and do not automatically become jointly owned "community property".

This system was a product of the post-World War II revision of the Civil Code. The pre-war Meiji Civil Code had a "management community system" where, although the wife could own property, the husband had comprehensive management rights over most spousal assets. During the post-war reforms, driven by the new Constitution's emphasis on gender equality, there were significant debates. Some reformers, recognizing that many women were full-time homemakers with limited opportunities to acquire property in their own names, advocated for a community property system, at least for income earned through joint spousal efforts. However, this proposal was ultimately rejected, partly due to concerns about the perceived complexity of community property systems and partly based on the argument that a homemaker's contributions could be adequately recognized and compensated through the mechanisms of property division upon divorce and spousal inheritance rights. The Supreme Court's 1961 reasoning closely mirrored these original legislative justifications.

Academic and Judicial Efforts to Temper Strict Separate Property Principles

While the Supreme Court affirmed the constitutional validity of the separate property system, its strict application could lead to perceived unfairness, especially for spouses (traditionally wives) who dedicated themselves to domestic labor and childcare, thereby facilitating the other spouse's income-earning activities, yet not directly acquiring assets in their own name.

In response, Japanese legal scholarship and, to some extent, lower court practice sought ways to ensure that the non-monetary contributions of such spouses were given due weight. A highly influential theory, proposed by scholars like Professor Wagatsuma Sakae, introduced the concept of "substantively co-owned property". This theory suggested that even if an asset was nominally registered in one spouse's name (e.g., the husband's), if it was acquired during the marriage through the couple's joint efforts and cooperation (including the wife's domestic contributions), it could be considered as being co-owned in substance by both spouses, at least for the internal purposes of their relationship and particularly upon its dissolution.

While the Supreme Court's pronouncements (including this 1961 decision and another in 1959 concerning property registered in a wife's name but funded by the husband) have emphasized that property acquired via one spouse's income is generally their separate property and that domestic labor alone doesn't automatically create co-ownership during the marriage, the concept of substantive co-ownership heavily influenced the development and practice of property division upon divorce (zaisan bunyo).

The Central Role of Property Division at Divorce (Zaisan Bunyo)

The Supreme Court in its 1961 ruling specifically pointed to property division at divorce as a key legal tool for achieving substantive equality between spouses and for recognizing their mutual contributions. This has indeed become the primary mechanism within the Japanese legal system for addressing the financial aspects of spousal cooperation during marriage. Over time, court practice in divorce cases has evolved to robustly recognize the value of a homemaker's contributions. The "1/2 rule," where marital assets accumulated through joint efforts are typically divided equally upon divorce, has become a well-established principle in practice, reflecting an understanding of marriage as a cooperative partnership. This practice effectively mitigates much of the potential substantive inequality that could arise from a rigid application of the separate property rule during the marriage.

Implications of the Ruling and Continuing Evolution

The 1961 Supreme Court decision was foundational in several respects:

- It definitively confirmed the constitutional validity of Japan's separate property system for married couples as defined in Civil Code Article 762(1).

- It endorsed the view that the constitutional mandate for "essential equality of the sexes" in marriage (Article 24) aims for substantive equality achieved over the entirety of the marital relationship and upon its dissolution, through a combination of legal rights including property division, inheritance, and spousal support, rather than by mandating an automatic co-ownership of all income and assets as they are acquired.

- For income tax purposes, it solidified the principle of individual-based taxation, where income is assessed to the spouse in whose name it was formally earned.

Despite this ruling, the discourse on spousal property rights in Japan has continued to evolve. There are ongoing academic and legislative discussions about how to further refine the system to better reflect modern family structures, diverse spousal roles, and the ideal of fairness. Proposals have included calls for clearer statutory definitions of what constitutes marital property subject to division and for specific protections for assets like the marital home, even within a predominantly separate property framework. The theoretical relationship between the separate property system during marriage and the mechanisms for financial adjustment upon its dissolution remains a topic of academic refinement.

Conclusion: A System of Balance

The Supreme Court of Japan's 1961 decision provided a critical constitutional endorsement of the nation's separate property system for married couples, particularly as it applied to the assessment of income for tax purposes. By interpreting constitutional equality as a substantive goal to be achieved through a holistic application of various family law provisions—including those for property division at divorce, inheritance, and spousal support—the Court found that the separate property rule did not inherently violate the principle of gender equality. While the letter of the separate property law, as articulated in Civil Code Article 762(1), remains, its practical application, especially in the context of marital dissolution, has been significantly shaped by judicial and societal efforts to ensure that the contributions of both spouses to the marital partnership are fairly recognized and compensated. This 1961 judgment remains a key reference point for understanding the legal and constitutional underpinnings of marital property and taxation in Japan.