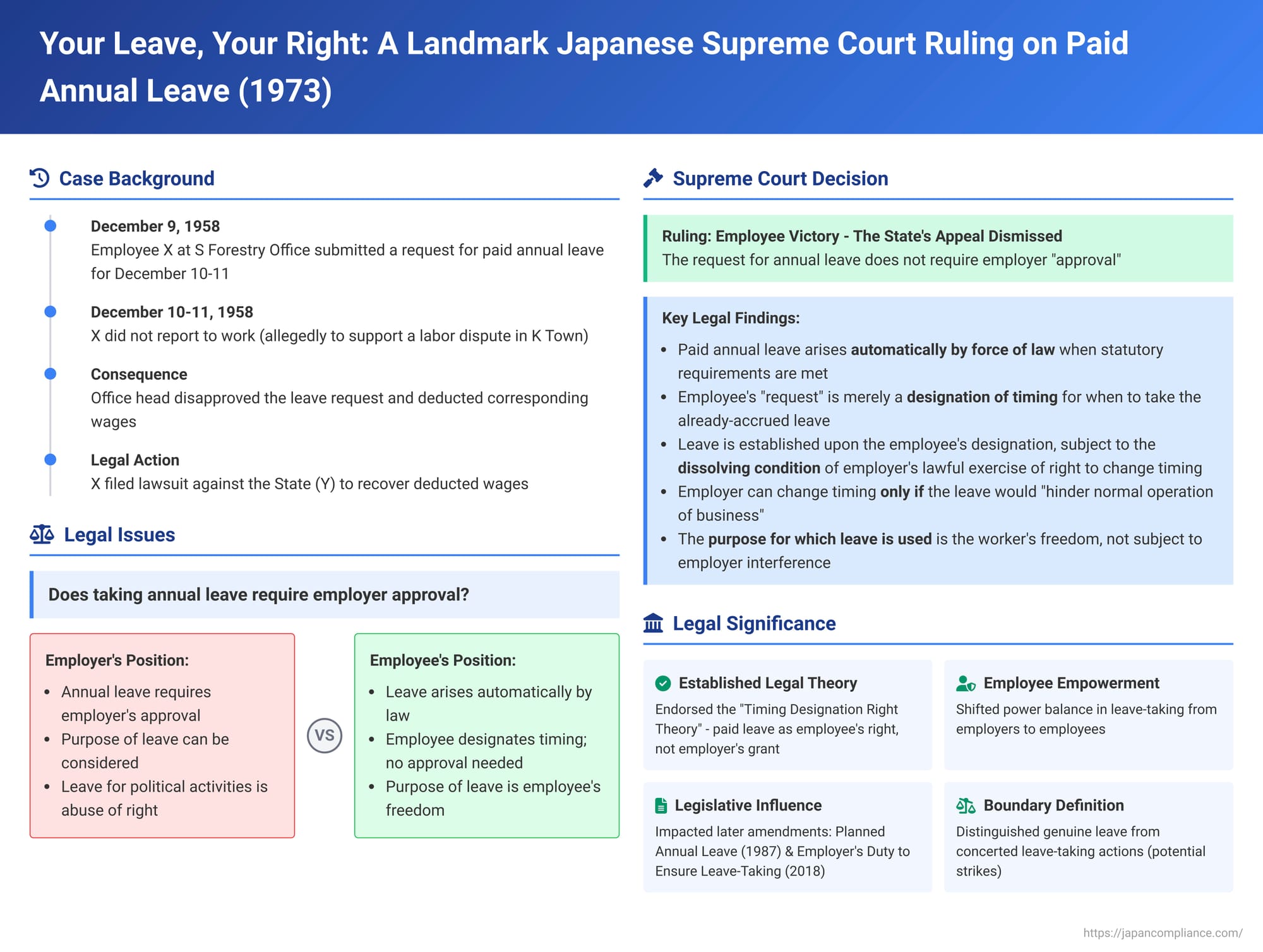

Your Leave, Your Right: A Landmark Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Paid Annual Leave (March 2, 1973)

On March 2, 1973, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a seminal judgment in what is commonly known as the "Shiraishi Forestry Office Case" (白石営林署事件). This ruling profoundly shaped the understanding of the legal nature of paid annual leave (年次有給休暇 - nenji yūkyū kyūka, often shortened to 年休 - nenkyū) under Article 39 of Japan's Labor Standards Act (LSA). It established that paid annual leave is a right that accrues automatically to eligible employees, and that the employee's act of specifying when they wish to take this leave (timing designation) is the primary mechanism for its establishment, rather than requiring explicit employer "approval".

The Dispute: A Leave Request Denied

The case involved Plaintiff X, an employee working at the S Forestry Office, which was part of the National Forestry Agency (Y, representing the State).

- On December 9, 1958, X submitted a request for paid annual leave for two consecutive days, December 10th and 11th. X subsequently did not report for work on these two days.

- The head of the S Forestry Office, however, disapproved X's leave request. The office treated these days as unauthorized absences (欠勤 - kekkin) and deducted the corresponding wages from X's salary.

- In response, X filed a lawsuit against Y (the State) to recover the deducted wages and other related payments.

Lower Courts Champion Employee's Prerogative

Both the first instance court (Sendai District Court) and the appellate court (Sendai High Court) ruled in favor of Plaintiff X, establishing important interpretations of the paid annual leave system.

- Sendai District Court: The District Court held that the timing requested by an employee for their paid annual leave automatically becomes the leave period. It asserted that there is no need to consider employer "approval" as a separate step distinct from the employer's statutory right to change the timing (時季変更権 - jiki henkōken) of the leave under specific circumstances. Even if work rules or established practices seemed to require employer approval for leave requests, such "approval," the court reasoned, merely signifies the employer's decision not to exercise their right to change the timing, and nothing more. The court found that the primary motivation for the S Forestry Office head's denial of leave (or purported exercise of the right to change timing) was to prevent X from traveling to support a labor dispute in the K Town/Area. This reason, the court concluded, did not constitute a situation that would "hinder the normal operation of the business," which is the sole ground upon which an employer can request a change in leave timing. Thus, the wage deduction was deemed illegal.

- Sendai High Court: The High Court upheld the District Court's decision, further elaborating on the nature of the leave right. It stated that once an employee fulfills the statutory requirements for paid annual leave (related to length of service and attendance rate under LSA Article 39, Paragraphs 1 and 2), the employer is unilaterally obligated by the State to exempt the employee from work duties for a specified number of days with pay. The employee, in turn, acquires a kind of Shurui Saiken (a legal term for a claim where the object is defined generically, in this case, a certain number of leave days) to be released from work obligations. The High Court emphasized that no separate act of "granting leave" or "approval" by the employer is necessary for this right to arise or for the corresponding employer obligation to be established.

The High Court also affirmed that the purpose for which an employee chooses to use their paid annual leave is, much like other public holidays, a matter of the employee's personal freedom. Unless the employer lawfully exercises their right to change the timing, an employee is entitled to designate their desired leave period and be released from work duties. The court explicitly rejected Y's argument that X's intention to use the leave to participate in what Y characterized as an illegal mass negotiation or labor dispute at the K Town/Area Forestry Office constituted an abuse of the right to paid annual leave or exceeded its intended scope.

Y (the State) appealed to the Supreme Court, primarily arguing that the lower courts had misinterpreted LSA Article 39 by not requiring an employer's positive act of "granting" leave for it to be effective.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Pronouncements

The Supreme Court dismissed the State's appeal, providing a definitive interpretation of the legal nature of paid annual leave.

I. Paid Annual Leave: An Automatic Right, Not a Granted Privilege

The Court declared that the right to paid annual leave "arises for the worker by force of law automatically when the requirements of LSA Article 39, Paragraphs 1 and 2 are fulfilled. It does not arise only upon the worker's request". This established that the accrual of leave is a statutory entitlement, not something dependent on a subsequent application process to come into existence.

II. The Employee's "Request" is a "Designation of Timing"

The Supreme Court clarified the meaning of the term "request" (請求 - seikyū) as used in LSA Article 39, Paragraph 3 (which corresponds to the current Article 39, Paragraph 5, dealing with the employer's right to change timing). It held that this "request" pertains only to the timing (時季 - jiki) of the leave. Crucially, the Court stated that "its meaning is nothing other than the 'designation' (指定 - shitei) of the leave timing". This means the employee is not merely asking for permission; they are exercising their right to specify when they will take their accrued leave.

III. Establishment of Leave and the Employer's Right to Change Timing

The judgment laid out the mechanism for leave establishment: "When a worker, within the scope of their entitled leave days, specifies the concrete start and end dates of the leave and thus designates the timing, unless objectively the circumstances prescribed in the proviso of Article 39, Paragraph 3 (now Paragraph 5) exist [i.e., hindering the normal operation of the business] AND the employer exercises the right to change the timing for this reason, the paid annual leave is established by said designation, and the duty to work on the relevant workdays is extinguished".

The Court further elucidated this by stating: "To put it succinctly, the effect of the designation of leave timing arises subject to the dissolving condition (解除条件 - kaijo jōken) of a lawful exercise of the employer's right to change the timing". A dissolving condition means the effect (leave establishment) takes place immediately upon designation, but can be undone if the specified condition (lawful exercise of jiki henkōken) occurs.

IV. The Irrelevance of Employer "Approval"

Based on the above, the Supreme Court firmly rejected the notion that employer approval is a prerequisite for taking paid annual leave: "There is no room for the notions of a worker's 'request for leave' or the employer's 'approval' thereof as requirements for the establishment of annual leave". The Court reasoned that if employer approval were required, it would reduce the employee's right to merely a contractual claim to request leave, necessitating further legal action to compel approval if unreasonably withheld, which would not align with the LSA's purpose.

V. Freedom to Use Leave for Any Purpose

The Supreme Court also unequivocally endorsed the principle of free use of annual leave: "The purpose for which annual leave is used is a matter outside the purview of the Labor Standards Act. It is the intent of the Act that how leave is used is the worker's freedom, not subject to interference by the employer". This means employers generally cannot inquire into, nor base their decisions regarding leave timing on, the employee's reasons for wanting the time off.

The Legal Theories Underpinning the Decision

The Supreme Court's judgment in the Shiraishi Forestry Office case can be understood within the context of evolving legal theories on the nature of paid annual leave in Japan.

- Early Debates: Initially, two main theories were prominent:

- The "Claim Right Theory" (請求権説 - seikyūken setsu) argued that because the timing of leave significantly impacts business operations, employer approval or consent was a necessary step for an employee to take leave.

- The "Formation Right Theory" (形成権説 - keiseiken setsu) contended that the employee's "request" for leave was not a petition for employer action but rather a unilateral act by the worker that, by itself, fixed the leave period and created the legal effect of release from work duties.

Despite their theoretical differences, both schools of thought tended to converge in practice, as the "Claim Right Theory" generally acknowledged that employers could only refuse leave if normal business operations were genuinely hindered, and the "Formation Right Theory" similarly recognized the employer's right to adjust leave timing under such circumstances.

- The "Two-Stage Theory" (二分説 - nibun setsu) and its Dominance: A more nuanced approach, known as the "Two-Stage Theory," subsequently emerged and became the prevailing view among legal scholars. This theory distinguishes between:

- The accrual of the right to a certain number of paid leave days upon meeting statutory conditions.

- The exercise of this right by designating the specific timing for the leave.

Within this Two-Stage Theory, several sub-theories developed. The most relevant to the Supreme Court's decision is the "Timing Designation Right Theory" (時季指定権説 - jiki shiteiken setsu). This sub-theory posits that upon meeting the LSA requirements, an employee acquires an abstract right to paid leave. The "request" mentioned in LSA Article 39, Paragraph 5 (then Paragraph 3) is interpreted as the employee's act of designating the specific timing for this accrued leave.

Other variants included the Shurui Saiken Theory (used by the High Court in this case), viewing the accrued leave as a generic claim for a number of days off, which is then specified by the worker's request, and the Choice Right Theory, viewing it as an employee's right to choose between working or taking leave on particular days.

The Supreme Court, in this judgment (and in the Kokutetsu Koriyama Kojo Jiken, another case decided on the same day), clearly aligned itself with the Two-Stage Theory, and specifically endorsed the "Timing Designation Right Theory". By stating that the employee's "request" is, in essence, the "designation" of the leave's timing (start and end dates), the Court empowered employees, making the establishment of leave dependent on their initiative, subject only to the employer's limited right to adjust the timing.

Subsequent Developments and Enduring Principles

The principles established in the Shiraishi Forestry Office case have had a lasting impact, though the LSA has seen further amendments aimed at promoting leave utilization.

- Planned Annual Leave (計画年休 - keikaku nenkyū): The commentary notes that while the Timing Designation Right Theory empowers individual workers, it doesn't inherently solve the issue of low leave uptake if workers do not proactively designate their leave. Some early proponents of this theory even envisioned "timing" (時季 - jiki) referring to broader seasons, within which employers might, in consultation, schedule specific leave dates to encourage more consolidated breaks. To address low utilization rates, the LSA was amended in 1987 to introduce the system of "planned annual leave" (LSA Article 39, Paragraph 6). This allows employers, through a labor-management agreement, to schedule a portion of employees' annual leave systematically. Such agreements can be binding even on employees who might individually prefer different timings for that portion of their leave. However, a minimum of five days of annual leave must always be reserved for the employee's free designation.

- Employer's Duty to Ensure Leave-Taking: Despite planned leave initiatives, overall leave utilization rates did not improve dramatically. Consequently, the LSA was further revised in 2018 (effective 2019) to introduce a new obligation for employers (LSA Article 39, Paragraph 7). This provision mandates that for employees entitled to 10 or more days of paid annual leave, employers must ensure that at least five of these days are taken by the employee within one year from the date they accrue. Any days taken based on the employee's own designation or through a planned leave agreement count towards fulfilling this five-day requirement. When determining the timing for these five days, employers are required to consult the employee and make efforts to respect their preferences. The "timing" (時季) in this context refers to specific leave dates.

- The Principle of Free Use and Its Boundaries: The Shiraishi Forestry Office judgment strongly affirmed the principle that employees are free to use their paid annual leave for any purpose they choose, without employer interference. However, the Supreme Court, in an obiter dictum (a comment not essential to the decision but of persuasive authority), addressed the scenario of a "concerted leave-taking struggle" (一斉休暇闘争 - issei kyūka tōsō). It suggested that if all employees in a workplace simultaneously submit leave requests with the intent of disrupting normal business operations, this action would, in substance, be a strike disguised as annual leave, not a genuine exercise of the right to annual leave. In such a case, the Court indicated, the employer's right to change timing would not apply, and the participating employees would not be entitled to wages for those days.

This obiter dictum has generated considerable academic discussion. Some scholars agree with the Supreme Court's distinction, while others argue that the principle of free use should extend even to such concerted actions, with the employer's recourse limited to exercising the right to change timing for essential personnel to maintain minimum operations. The commentary author expresses support for the latter view, citing constitutional guarantees related to a minimum standard of living, working conditions, and the right to collective action.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Employee Empowerment

The 1973 Supreme Court judgment in the Shiraishi Forestry Office case remains a foundational decision in Japanese labor law. It decisively established that paid annual leave is an automatic right for eligible employees, not a privilege to be granted by the employer. The employee's designation of their preferred leave time is paramount, with the leave taking effect unless the employer can demonstrate that it genuinely hinders the normal operation of the business and lawfully exercises their right to request a change in timing. Furthermore, the Court's confirmation that the employee's purpose for taking leave is their private affair reinforces the personal nature of this entitlement. While subsequent legislative changes have aimed to further promote leave-taking, the core principles of employee initiative and freedom of use articulated in this landmark case continue to underpin the right to paid annual leave in Japan.