"You Started It": A 2008 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Provoked Self-Defense

Decision Date: May 20, 2008

The right to self-defense is a cornerstone of criminal law, granting an individual the right to use force to protect themselves from an imminent and unjust attack. But this right is predicated on the idea of innocence—that the person defending themselves is the victim of unprovoked aggression. This raises a difficult question that cuts to the core of the doctrine: Can a person who starts a fight then claim self-defense when their victim fights back?

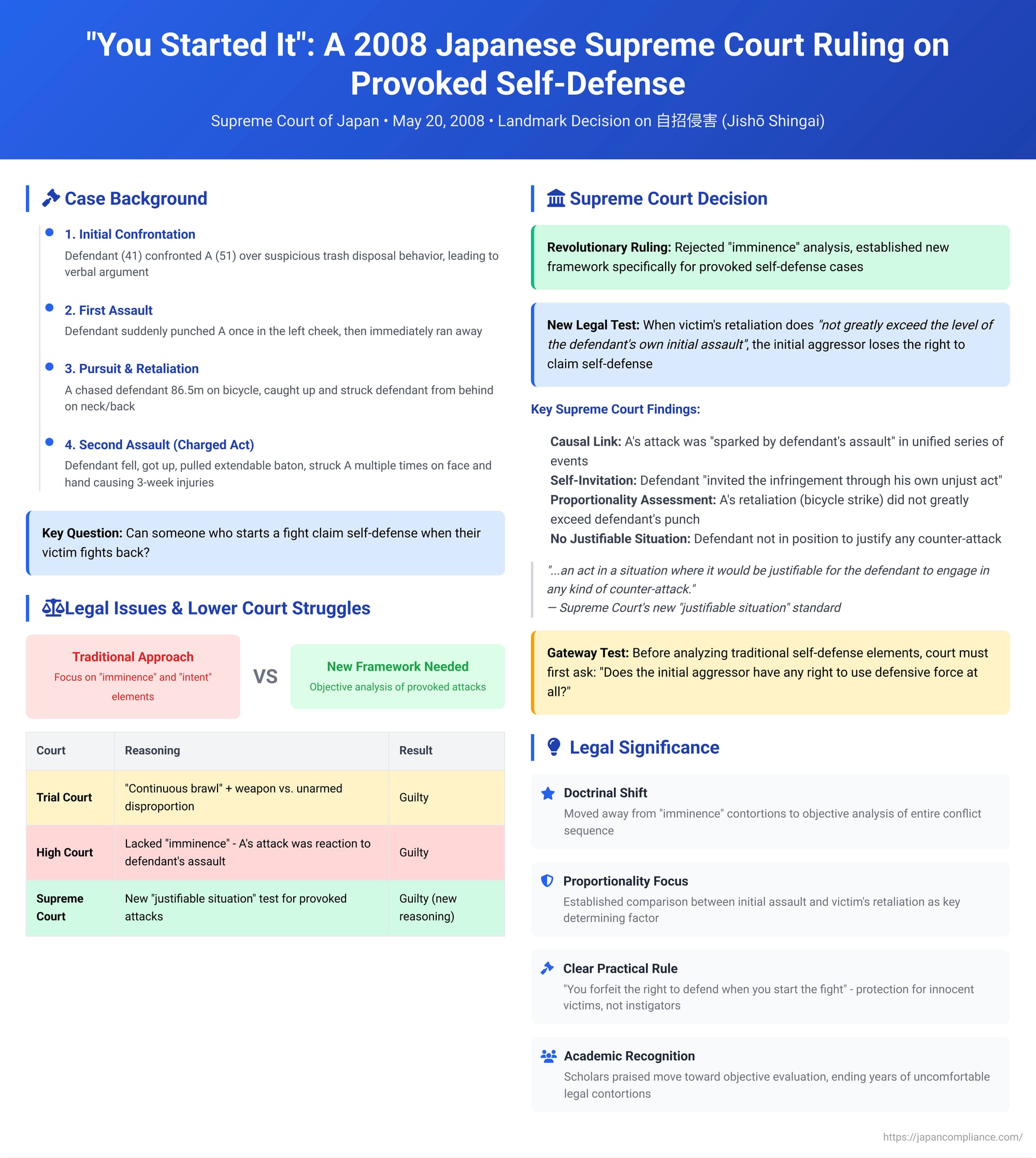

On May 20, 2008, the Supreme Court of Japan issued a landmark decision that directly confronted this issue of "provoked self-defense" (jishō shingai). The case, which began with a minor street argument that escalated into a two-part assault, saw the Court set aside traditional analyses of "imminence" and "intent" and establish a new, objective framework for determining when an initial aggressor forfeits their right to claim self-defense.

The Factual Background: A Street Argument and a Chain of Violence

The incident began with a seemingly trivial dispute. The defendant, a 41-year-old man, was walking home when he saw A, a 51-year-old man, disposing of trash at a public collection point while still seated on his bicycle. The defendant found this behavior suspicious, confronted A, and a verbal argument ensued.

The confrontation quickly turned physical in a sequence of four distinct acts:

- The First Assault: The defendant suddenly punched A once in the left cheek with his fist.

- The Flight: Immediately after throwing the punch, the defendant turned and ran away.

- The Pursuit and Retaliation: A, shouting "Wait!", got on his bicycle and chased the defendant. He caught up to him approximately 86.5 meters down the sidewalk and, while still on his bike, struck the defendant forcefully from behind on the upper back or neck with his outstretched right arm.

- The Second Assault (The Act in Question): The force of A's blow knocked the defendant to the ground. The defendant got back up, pulled out a special extendable baton that he carried for self-protection, and struck A several times on the face and on the left hand as A tried to shield himself. This second assault by the defendant caused injuries to A, including facial contusions and a broken finger, that required about three weeks of medical treatment.

The defendant was charged with the crime of causing bodily injury for this final act of striking A with the baton.

The Journey Through the Courts: Searching for the Right Legal Framework

The lower courts agreed that the defendant was guilty but struggled to articulate the precise legal reason why his claim of self-defense should fail.

- The Trial Court: The first-instance court rejected the self-defense claim on two grounds. First, it characterized the entire incident as a "continuous brawl," a situation in which the law generally does not permit a claim of self-defense. Second, it noted that the defendant used a weapon (the baton) against an unarmed person (A), suggesting a lack of proportionality.

- The High Court: The appellate court also upheld the conviction but used a different and more technical legal rationale. It focused on the "imminence" requirement for self-defense. The court reasoned that because A's attack was a direct and immediate reaction to the defendant's own initial assault, the situation lacked the necessary quality of "imminence" from the defendant's perspective, thereby disqualifying the self-defense claim. This reasoning was based on a 1977 Supreme Court precedent that dealt with anticipated (but not provoked) attacks.

The defendant, disagreeing with this legal reasoning, appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's New Approach: Beyond Imminence

The Supreme Court upheld the defendant's conviction, but in doing so, it explicitly rejected the High Court's reasoning based on "imminence." The Court found that forcing the facts into the "imminence" framework was inappropriate. Instead, it carved out a new and distinct legal standard specifically for cases of provoked attacks.

The Core Legal Principle:

The Court first established the direct causal link between the defendant's actions and the retaliation he faced. It found that A's attack was "sparked by the defendant's assault" and was part of a "single, unified series of events in a proximate location immediately thereafter." On this basis, the Court declared that the defendant had "invited the infringement through his own unjust act."

The New Test for Provoked Attacks:

Having established that the defendant was the initial aggressor, the Court laid down its new test. It held that in a situation where the victim's retaliation (A's blow from the bicycle) does "not greatly exceed the level of the defendant's own initial assault", the defendant's subsequent counter-attack (hitting A with the baton) cannot be considered:

"...an act in a situation where it would be justifiable for the defendant to engage in any kind of counter-attack."

Because the defendant was not in a "justifiable situation" to begin with, his claim of self-defense was precluded from the outset. The conviction was upheld, but on this new and different legal ground.

A Deeper Dive: The Legal Theory of "Jishō Shingai"

This 2008 decision marked a significant doctrinal shift in Japanese self-defense law. For years, cases involving provocation were often uncomfortably shoehorned into the existing legal frameworks for self-defense, particularly the element of "imminence" or the defender's subjective "intent." Legal scholars had long criticized this approach. Arguing that an attack lacks "imminence" when a person is literally being struck is a factual contortion. The 2008 Court effectively created a new, preliminary step in the analysis for provoked attack scenarios.

The Proportionality of Retaliation:

The core of the Supreme Court's new test is a comparison of proportionality between the initial unjust act and the immediate retaliation. If the victim's response is a roughly proportional reaction to the violence initiated by the first aggressor, the first aggressor loses the right to claim self-defense against that response. In essence, the law will not allow the person who started the fight to claim victim status when they receive a predictable and not-grossly-disproportionate reply.

The "Justifiable Situation" Standard:

The Court's key phrasing—that the defendant was not in a "situation where it would be justifiable to counter-attack"—is a powerful new concept. It functions as a gateway test. Before a court even needs to analyze the traditional elements of self-defense (imminence, necessity, proportionality of the final defensive act), it first asks a threshold question: Given that the defendant initiated the conflict, do they have any right to use defensive force at all? If the victim's retaliation is within a predictable and proportional range, the answer is no. The door to a self-defense claim is closed before it can even be opened.

This new standard avoids the logical acrobatics of trying to deny the "imminence" or "injustice" of the retaliatory attack in the abstract. A's act of striking the defendant was, in isolation, an imminent and unjust assault. However, the Court's ruling establishes that relative to the defendant, who caused the situation, it was not the kind of unjust attack that triggers the exceptional right of self-defense.

Unresolved Questions and Academic Debate:

While the Court's ruling provides a practical solution, legal scholars continue to debate the precise theoretical underpinnings. Some argue that the Court's approach is essentially finding that the victim's retaliation lacks "injustice" vis-à-vis the initial aggressor. Others suggest the best framework would be to completely disqualify self-defense for the initial aggressor and instead analyze their final counter-attack under the much stricter rules of "Necessity" (kinkyū hinan). The doctrine of necessity requires that the act be a last resort to avert a greater danger and that the harm caused not exceed the harm avoided. Applying this standard would mean an initial aggressor could only use force if they could not retreat and only to the extent necessary to save themselves from a disproportionately severe retaliatory attack. While the Supreme Court did not explicitly adopt this theory, its new standard moves in a similar direction by severely restricting the initial aggressor's right to use force.

Conclusion: You Forfeit the Right to Defend When You Start the Fight

The 2008 Supreme Court decision on provoked self-defense established a clear and important principle in Japanese criminal law. It moved the legal analysis away from contorted interpretations of imminence and subjective intent, and toward a more objective evaluation of the entire conflict. The ruling's practical message is unambiguous: if you unjustifiably initiate a physical conflict, you forfeit your right to claim self-defense against a foreseeable and proportionate response. The law of self-defense is designed to protect the innocent victims of aggression; it is not a shield for those who instigated the violence in the first place.