Wrong Label, Right Challenge? Navigating Suits Over Flawed Shareholder Resolutions in Japan

Case: Action for Confirmation of Nullity of a Shareholders' Meeting Resolution

Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Judgment of November 16, 1979

Case Number: (O) No. 410 of 1979

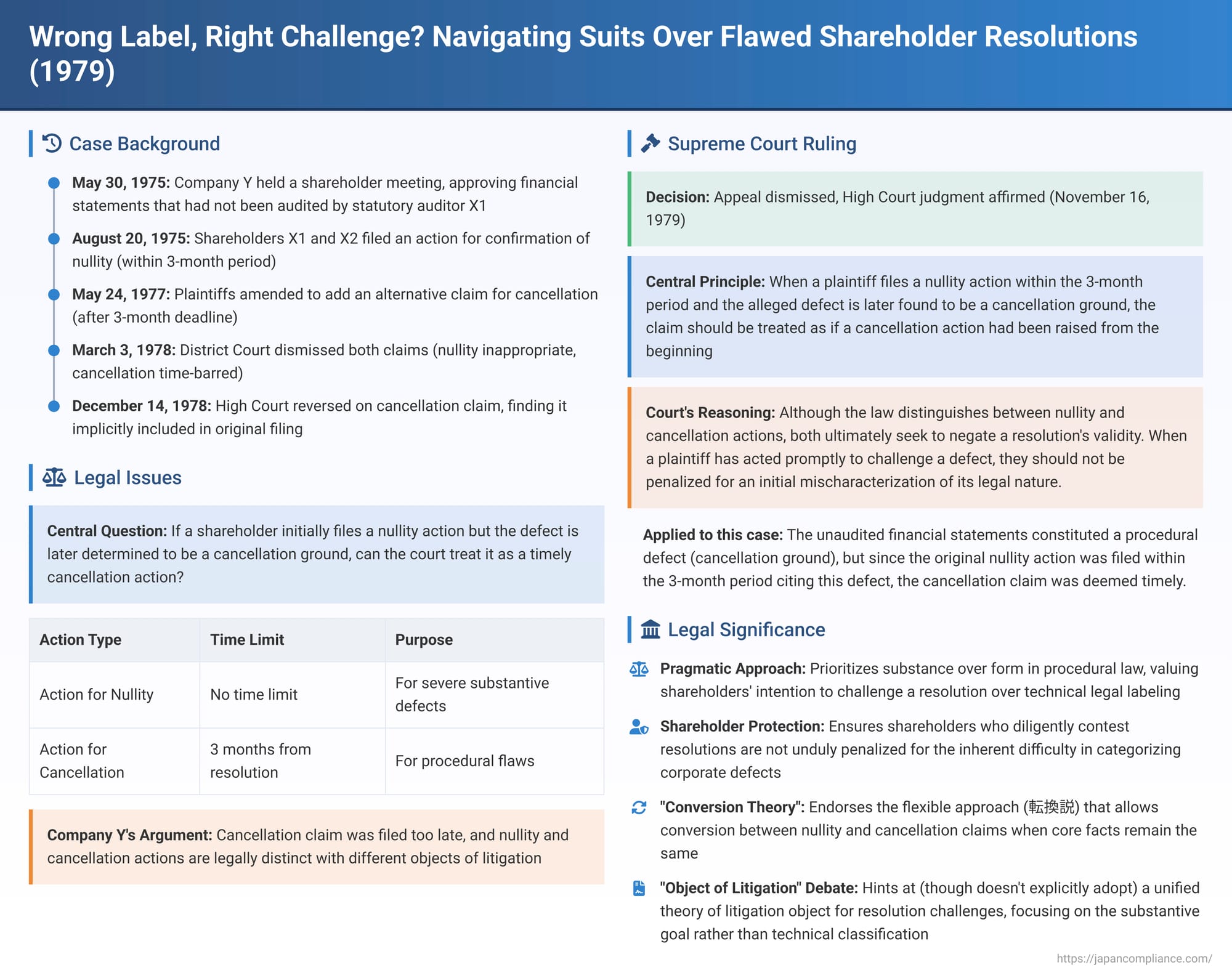

Shareholders challenging a company resolution due to perceived flaws face a critical initial decision: what type of lawsuit should they file? Japanese company law offers distinct routes, such as an action to cancel a resolution or an action to confirm its nullity, each with its own requirements and, crucially, different time limits. What happens if a shareholder, acting in good faith, sues to declare a resolution null and void, only for a court to later determine that the defect, while serious, is technically a ground for cancellation – a type of action for which the short statutory deadline has since passed? A key Supreme Court decision on November 16, 1979, provided much-needed clarity on this procedural predicament, emphasizing substance over the initial legal label.

The Unaudited Financials: Facts of the Case

The dispute involved Company Y. On May 30, 1975, Company Y held its ordinary general shareholders' meeting, at which various resolutions were passed, including the approval of the company's financial statements (comprising the business report, balance sheet, and profit and loss statement) for its third fiscal period.

However, there was a significant problem: these financial statements had not been audited by the company's statutory auditor (who, in this case, was X1, one of the plaintiffs) before being presented to and approved by the shareholders' meeting.

On August 20, 1975 – well within the three-month statutory period for filing an action to cancel a shareholder resolution – X1 and another shareholder, X2, initiated legal proceedings. They filed an "action for confirmation of nullity" (mukō kakunin no uttae) of the resolution approving the financial statements. Their argument was that the submission of unaudited financial statements was an illegal act, rendering any resolution approving such statements void from the outset.

Company Y contested this, arguing that even if the statements were unaudited, this did not automatically make them "illegal" in a way that would lead to the resolution's nullity. They asserted that such a flaw was not a valid basis for a nullity action.

Later, on May 24, 1977, while the case was still pending in the court of first instance, the plaintiffs (X1 and X2) amended their lawsuit. They added an "alternative claim" (yobiteki seikyū) seeking the "cancellation" (torikeshi) of the resolution approving the financial statements. This explicit claim for cancellation was introduced after the three-month deadline for filing a standalone cancellation action had expired.

The Legal Labyrinth: Lower Court Decisions

The court of first instance (Yokohama District Court, judgment dated March 3, 1978) ruled against the plaintiffs on both claims:

- Regarding the primary claim for nullity, the court held that the failure to have the financial statements audited before the shareholders' meeting was indeed a legal violation. However, it deemed this a ground for cancellation of the resolution, not for its outright nullity, unless the plaintiffs could show that the financial statements themselves contained falsehoods or other substantive defects. Since the plaintiffs had not made such assertions about the content, the nullity claim was dismissed.

- As for the alternative claim for cancellation, which was added much later, the court dismissed it as untimely. It reasoned that the claim had been filed after the strict three-month statute of limitations for cancellation actions had lapsed.

The plaintiffs appealed. The appellate court (Tokyo High Court, judgment dated December 14, 1978) took a different stance on the crucial issue of timeliness:

- On the primary claim for nullity, it concurred with the first instance court: the defect (lack of audit) was a ground for cancellation rather than nullity.

- However, concerning the alternative claim for cancellation, the High Court found that the first instance court's dismissal on timeliness grounds was improper. It reasoned that if shareholders file a lawsuit within the prescribed three-month period seeking to negate the effect of a resolution due to a specific defect, their action should be interpreted as preliminarily or implicitly including a claim for cancellation based on that defect, even if it was initially framed as a nullity action. The High Court argued that as long as the plaintiffs' intention to challenge the resolution's validity based on the alleged defect was clear, it would be unfair to penalize them for an initial misjudgment of the defect's precise legal classification (i.e., as a nullity ground versus a cancellation ground). To hold otherwise would place the entire burden of correctly categorizing the legal nature of the defect squarely on the plaintiff from the outset. Consequently, the High Court considered the cancellation claim timely and remanded that part of the case back to the District Court for further proceedings.

Company Y then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

Company Y's Arguments to the Supreme Court

Company Y argued that the High Court had erred. Its main contentions were:

- The alternative claim for cancellation was unequivocally filed after the statutory period for such actions had expired, violating the then-Commercial Code Article 248, Paragraph 1.

- An action for confirmation of nullity and an action for cancellation are legally distinct, having different "objects of litigation" (soshōbutsu). The High Court's approach of treating a nullity claim as implicitly including a cancellation claim would blur these distinctions and create uncertainty in legal proceedings.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Substance Over Form

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of November 16, 1979, dismissed Company Y's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's more flexible and plaintiff-friendly approach.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: A Unified Purpose in Challenging Resolutions

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Distinction Between Cancellation and Nullity Grounds: The Court acknowledged that the Commercial Code (and now the Companies Act) indeed distinguishes between actions for cancellation of a shareholder resolution and actions for confirmation of its nullity. Grounds for cancellation typically involve procedural flaws in the convening of the meeting or the method of resolution. These are generally considered less severe than grounds for nullity, which often relate to serious substantive defects in the content of the resolution itself, or grave procedural violations.

- Rationale for Stricter Cancellation Requirements: Because cancellation grounds are often seen as less severe, and in the interest of promoting legal stability in corporate affairs, the law imposes stricter conditions on cancellation lawsuits. These include limiting who has standing to sue and imposing a short, three-month statute of limitations from the date of the resolution.

- Common Underlying Purpose: Despite these distinctions, the Supreme Court emphasized a crucial commonality: both cancellation grounds and nullity grounds are, at their core, reasons for negating the legal validity of the shareholder resolution. There is no fundamental difference between them in this ultimate objective.

- The Core Principle of the Judgment: Flowing from this, the Court laid down its key principle:

If, in an action seeking confirmation of a resolution's nullity, the defect alleged by the plaintiff as a nullity ground is ultimately found by the court to be a ground for cancellation, AND if the requirements for bringing a cancellation action (such as plaintiff standing and, critically, the initial filing of the nullity action being within the three-month period for cancellation) are otherwise satisfied, then the claim should be treated as if a cancellation action had been raised from the moment the original nullity action was filed. This is true even if an explicit assertion or formal pleading of "cancellation" is made after the three-month period has expired.

Applying this principle, the Supreme Court concluded that the cancellation action in the present case was effectively filed in time, as the original nullity action (which detailed the same defect of unaudited financials) was lodged within the three-month window. The High Court's judgment, leading to the same practical outcome, was therefore correct.

Analysis and Implications: Balancing Formality and Fairness

This Supreme Court judgment is highly significant for its pragmatic approach to a common procedural challenge in corporate litigation.

- The Challenge of Categorizing Defects: Japanese company law provides distinct legal avenues for challenging flawed shareholder resolutions: actions for cancellation (Companies Act Article 831), actions for confirmation of non-existence, and actions for confirmation of nullity (Companies Act Article 830). However, the dividing lines between what constitutes a cancellation ground versus a nullity ground (or even a ground for non-existence) can be notoriously unclear. This lack of sharp distinction forces plaintiffs to make an initial, often difficult, legal assessment of the severity and nature of the defect, a judgment that carries risks, as this case illustrates. The defect in this case—the use of unaudited financial statements—was treated by the courts as a cancellation ground (a violation of law in the convocation procedure or resolution method). However, some legal commentators argue that given the fundamental importance of the audit process, such a flaw could arguably be considered a more serious nullity ground.

- Evolution from Stricter Judicial Views: Before this Supreme Court decision, the prevailing judicial approach, particularly in lower courts, was often more rigid. This "strict view" generally held that if a plaintiff chose the wrong legal label for their challenge (e.g., suing for nullity when the defect was only a cancellation ground), the court would likely dismiss the claim based on the chosen framework. This approach, rooted in a traditional understanding of the "object of litigation" (soshōbutsu), was criticized for being overly formalistic and for placing an undue burden on shareholders seeking redress.

- Endorsement of a More Flexible Approach: This Supreme Court judgment decisively endorsed a more flexible stance, often referred to as the "conversion theory" (tenkan-setsu) by commentators. This view allows a court to treat a timely filed nullity claim as encompassing a cancellation claim if the underlying facts support such a characterization and the basic requirements for a cancellation action (like timely initial filing and plaintiff standing) are met. The emphasis shifts from the plaintiff's initial legal nomenclature to their substantive intent to challenge the resolution's validity based on the alleged defect.

- The "Object of Litigation" Debate: This decision touches upon a long-standing debate in Japanese civil procedure regarding the "object of litigation." The strict view posits that an action for nullity and an action for cancellation are distinct legal claims with separate objects. An alternative "unitary theory" (soshōbutsu ichigenron) suggests that all actions challenging a resolution's validity (be it for cancellation, nullity, or non-existence) essentially share a single object: a judicial declaration negating the resolution's effect. Under this unified theory, the specific legal ground (cancellation, nullity, etc.) is merely the reason or method of attack, not a distinct object of litigation itself. While the Supreme Court in this 1979 case did not explicitly adopt the unitary theory, its practical outcome – allowing the challenge to proceed despite the initial labeling – aligns with the functional benefits of such a theory, simplifying the process for plaintiffs and avoiding dismissals on purely formal grounds.

- Procedural Implications: The judgment prioritizes the substance of the shareholder's challenge. It ensures that if a shareholder diligently brings a defect to the court's attention within the critical early timeframe (the three months for cancellation actions), their right to challenge is not automatically forfeited due to a technical mislabeling of the legal nature of that defect. While the plaintiffs in this case did eventually add an alternative claim for cancellation, the Supreme Court's reasoning suggests that the timely filing of the nullity action itself, detailing the relevant facts, was the key factor. Legal commentary has discussed whether a court can make this "conversion" automatically or if some action from the plaintiff (like a motion to amend or clarify the claim) or proactive clarification by the court is necessary, particularly in light of the principle of party disposition in litigation.

- Balancing Legal Stability and Shareholder Protection: The decision strikes a balance. The short statute of limitations for cancellation actions serves the important purpose of ensuring legal stability in corporate affairs. However, this judgment prevents that rule from being used to unfairly thwart shareholders who have promptly taken action to contest a resolution, simply because they initially misjudged the complex legal classification of its flaws.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's November 16, 1979, ruling represents a significant step towards a more practical and equitable approach to adjudicating challenges against flawed shareholder resolutions in Japan. By allowing a timely filed nullity action to serve as a basis for a cancellation claim if the alleged defect warrants it, the Court prioritized the substance of the grievance over the strictness of the initial legal form. This decision ensures that shareholders who act promptly to contest a resolution's validity are not unduly penalized for the inherent difficulty in categorizing corporate defects, thereby reinforcing meaningful shareholder oversight and access to justice.