Workplace Speech and Discipline: Japan's Supreme Court on Political Plates and Protest Leaflets (December 13, 1977)

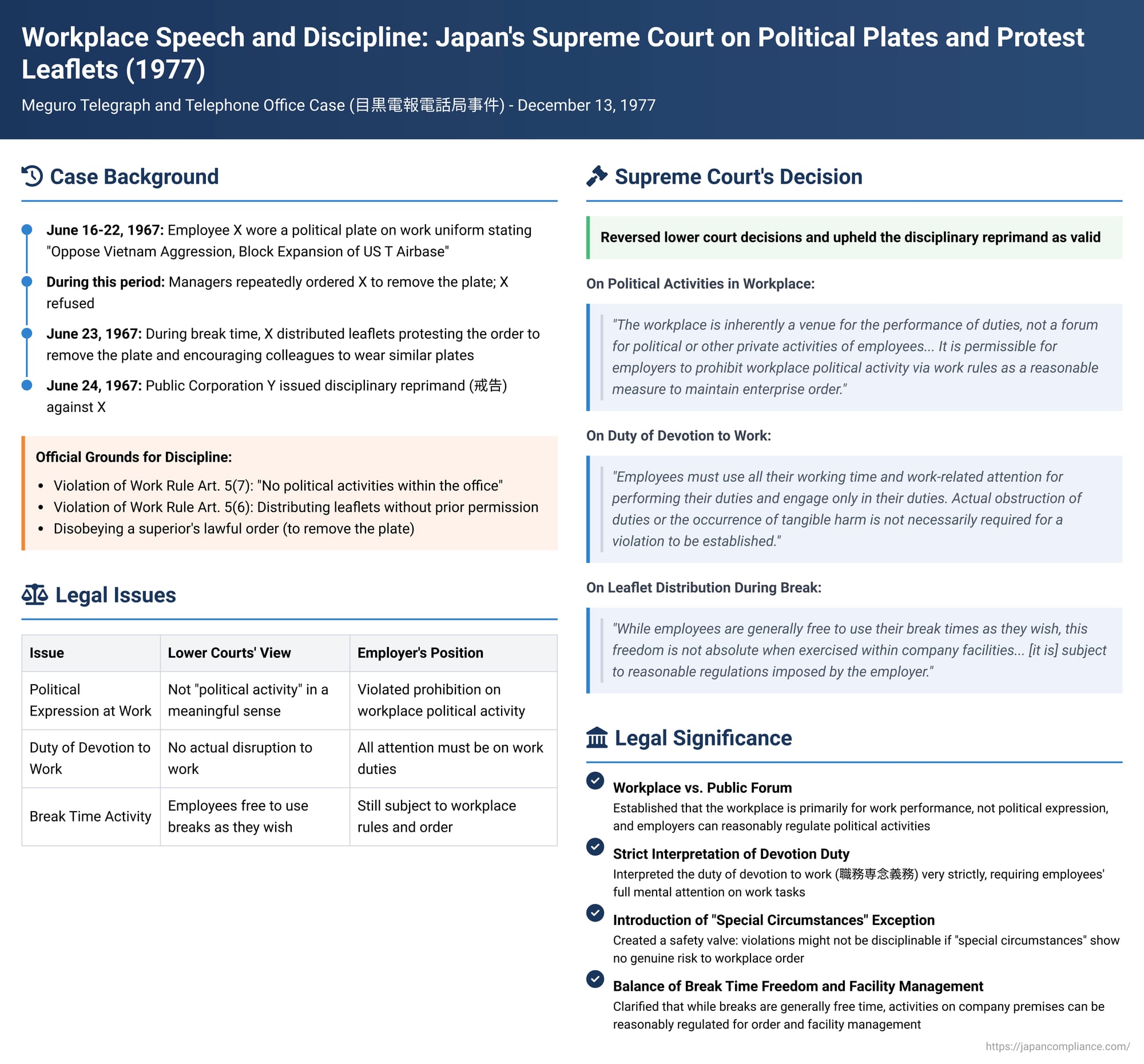

On December 13, 1977, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment in a case commonly known as the "Meguro Telegraph and Telephone Office Case" (目黒電報電話局事件). This ruling addressed the extent to which an employer, particularly a public corporation at the time, could restrict an employee's political expression and related activities within the workplace. The case delved into the validity of work rules prohibiting political activities, the scope of an employee's duty of devotion to work (職務専念義務 - shokumu sennen gimu), and the regulation of activities such as leaflet distribution during break times.

An Employee's Protest: A Plate and Leaflets

The plaintiff, X, was an employee of Public Corporation Y (a public entity similar to the then-Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Public Corporation) working at its M Telegraph and Telephone Office. The dispute arose from two distinct but related actions taken by X:

- Wearing a Political Slogan Plate: For a continuous period from June 16 to June 22, 1967, X wore a plastic plate affixed to the left breast of X's work attire while on duty. The plate, featuring white lettering on a blue background, bore the slogan: "Oppose Vietnam Aggression, Block Expansion of US T Airbase." X's stated motivation for wearing the plate was a belief that opposing the Vietnam War contributed to peace in Japan and a desire to share these sentiments with workplace colleagues, as X believed the T Airbase was being used in connection with the war.

Managers at the M Office, including the office director, repeatedly instructed X to remove the plate. X, however, refused to comply with these instructions. - Distributing Protest Leaflets: Believing the order to remove the plate was unjust, X decided to protest this directive. During a designated break time on June 23, 1967, X distributed several dozen leaflets titled "An Appeal to Everyone in the Workplace." This distribution took place in the office's break room and cafeteria, where X handed them directly to other employees, and in some work areas without designated break rooms, by placing them on employees' desks. This was done without obtaining prior permission from the office's administrative manager (the head of the general affairs section), as required by company rules. The leaflets detailed X's interaction with management over the plate, criticized management's stance as an attempt to suppress union activity and political awareness to facilitate rationalization plans, and called on colleagues to wear similar plates or badges expressing workplace demands.

Disciplinary Action and the Legal Challenge

On June 24, 1967, Public Corporation Y imposed a disciplinary reprimand (戒告 - kaikoku) on X. The stated grounds for this action were:

- The act of wearing the political slogan plate during working hours violated Article 5, Paragraph 7 of Public Corporation Y's Work Rules, which stated: "Employees shall not engage in election campaigning or other political activities within the office/station."

- The act of distributing leaflets without prior managerial permission violated Article 5, Paragraph 6 of the Work Rules, which mandated such permission for activities like speeches, meetings, posting notices, or distributing leaflets within the office/station.

- Both these violations were cited as falling under Article 59, Paragraph 18 of the Work Rules ("violation of the provisions of Article 5"), which was a specified cause for disciplinary action under Article 33, Paragraph 1 of the Public Corporation Act. Additionally, X's refusal to obey the order to remove the plate was cited as a breach of Article 59, Paragraph 3 ("disobeying a superior's order").

X subsequently filed a lawsuit seeking a declaration that this disciplinary reprimand was invalid. The Tokyo District Court (first instance) and the Tokyo High Court (on appeal) both ruled in favor of X. They found, among other things, that X's plate-wearing did not constitute "political activity" in a meaningful sense and that the leaflet distribution did not cause any actual disruption to workplace order, thus concluding that valid grounds for disciplinary action did not exist. Public Corporation Y then appealed these decisions to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Reversal: Upholding the Disciplinary Action

The Supreme Court overturned the judgments of both the High Court and the District Court, ultimately dismissing X's claim and upholding the validity of the disciplinary reprimand. The Court meticulously analyzed each aspect of X's conduct in relation to the work rules and relevant legal principles.

I. Validity of Prohibiting Political Activity in the Workplace

- Nature of the Employment Relationship: The Court first clarified that while the employment relationship within a public corporation like Y might be subject to somewhat different regulations than in purely private enterprises, it is fundamentally a relationship governed by private law. Its essential nature is not different from that between a private employer and its employees.

- Workplace as a Place for Work, Not Politics: In private enterprises, the Court reasoned, the workplace is inherently a venue for the performance of duties, not a forum for political or other private activities of employees. Employees do not possess an intrinsic right to engage in political activities within the workplace.

- Risk to Enterprise Order: Workplace political activities carry a strong risk of disrupting enterprise order. They can lead to political conflicts among employees and, by utilizing company facilities, can interfere with the employer's management of those facilities.

- Reasonableness of the Ban: "Therefore, it is permissible for private employers to prohibit workplace political activity via work rules as a reasonable measure to maintain enterprise order." The Court found that Public Corporation Y's Work Rule Art. 5(7), which aimed to maintain order and decorum, was such a reasonable provision.

- The "Special Circumstances" Exception: However, the Court introduced an important caveat: even if an employee's conduct formally appears to violate such a prohibition, if "special circumstances exist where it poses no real risk of disrupting order and decorum within the office/station, it would not constitute a violation of the said rule."

II. Plate-Wearing as a Breach of the Duty of Devotion to Work (Shokumu Sennen Gimu)

The Supreme Court then assessed X's act of wearing the political slogan plate during working hours, specifically in the context of the "duty of devotion to work" (職務専念義務 - shokumu sennen gimu), which was stipulated in Article 34, Paragraph 2 of the Public Corporation Act at the time.

- Strict Interpretation of Devotion Duty: The Court interpreted this duty strictly: "This means employees must use all their working time and work-related attention for performing their duties and engage only in their duties. Actual obstruction of duties or the occurrence of tangible harm is not necessarily required for a violation to be established."

- Application to X's Conduct: X's act of wearing the plate during work hours was characterized as an appeal to workplace colleagues and an action not directly related to the performance of X's official duties as an employee of Public Corporation Y. The Court stated: "Even if, from the perspective of physical activity, it did not cause any particular hindrance to the performance of work, from the perspective of mental activity, it can be construed that all of X's attention was not directed towards the performance of duties."

- Disruption of Order: Consequently, the Court found that X's plate-wearing violated the duty to devote all attention to work. This, in turn, was deemed to have "disrupted the discipline and order within the office/station that requires devotion to duty." The Court further noted that X's conduct also risked distracting other employees and hindering their concentration on their duties. Thus, the "special circumstances" exception (where no risk to order exists) did not apply.

- Lawfulness of the Removal Order: Since the plate-wearing itself was a violation, the superiors' orders to X to remove the plate were deemed lawful. X's refusal to comply with these lawful orders therefore constituted a separate, valid ground for disciplinary action ("disobeying a superior's order").

III. Leaflet Distribution During Break Time

Regarding X's distribution of leaflets without permission during a break time, the Supreme Court found:

- Formal Violation: The act was a clear formal violation of Work Rule Art. 5(6), which required prior managerial permission for such distributions.

- Break Time Freedom vs. Facility Management: While employees are generally free to use their break times as they wish (LSA Article 34, Paragraph 3), this freedom is not absolute when exercised within company facilities. It is subject to reasonable regulations imposed by the employer for the purpose of managing its facilities and maintaining overall workplace order. A rule requiring permission for leaflet distribution was considered a reasonable restriction from this perspective, as such activities could potentially interfere with facility management or the ability of other employees to freely use their break time, and depending on the content, could disrupt enterprise order.

- Assessing "Special Circumstances" for Leaflet Distribution: Similar to the political activity ban, the Court acknowledged that if "special circumstances" showed that the unpermitted leaflet distribution posed no risk of disrupting order and decorum, it might not constitute a punishable violation.

- Content and Purpose of X's Leaflets: However, in X's case, the Court found no such special circumstances. It emphasized the content and purpose of the leaflets: "Although the distribution itself was conducted peacefully during a break time, primarily in the break room and cafeteria, and there were no particular issues with the manner of distribution, the action was taken with the intent of protesting a lawful order from superiors. Furthermore, its content included protesting this lawful order and also inciting illegal acts such as engaging in political activity and wearing plates within the office/station."

- Disruption of Order: This content, the Court concluded, "was contrary to workplace discipline and carried the risk of disrupting order within the office/station." Therefore, even though carried out during a break, the unpermitted distribution was a substantive violation of the work rules and a valid ground for disciplinary action.

Unpacking the Judgment: Key Themes and Debates

This Supreme Court judgment touches upon several enduring themes in Japanese labor law.

- Public vs. Private Employment: While acknowledging some differences, the Court largely treated the employment relationship within the public corporation as analogous to that in private enterprises for the purpose of workplace discipline and order. This made the ruling influential for the private sector as well.

- Restrictions on Political Activity: The Court endorsed the "Abstract Danger Theory," allowing employers to reasonably prohibit political activities within the workplace due to the general risk they pose to enterprise order. However, its introduction of a "special circumstances" exception (where no real risk to order exists) has been seen by some commentators as a move that brings its practical application closer to the "Concrete Danger Theory" (which requires a more specific and demonstrable risk).

- The Stringent "Duty of Devotion to Work": The Supreme Court's interpretation of the shokumu sennen gimu as requiring employees to dedicate all their mental attention to their duties, without needing proof of actual harm for a violation, is notably strict. This aspect of the ruling has drawn considerable criticism from legal scholars, many of whom argue it is an overreach, potentially allowing employers to regulate employees' inner thoughts. A more widely supported alternative, often associated with a supplementary opinion by Justice Ito in a later case (the Taisei Kanko Case, 1982), suggests that this duty should be understood as an obligation to faithfully perform one's tasks, and that employee actions that do not concretely impede work performance or harm the employer's business should not necessarily be considered violations.

- Break Time Activities on Company Premises: The judgment confirms that while employees have a right to use their break times freely, this freedom is subject to reasonable employer regulations necessary for managing company facilities and maintaining overall workplace order. Rules requiring permission for activities like leaflet distribution were deemed generally reasonable. However, the assessment of whether an unpermitted distribution actually warrants discipline again hinges on whether it genuinely disrupts or risks disrupting workplace order, with the "special circumstances" exception potentially applying. Later Supreme Court cases have sometimes found such "special circumstances" to exist when leaflet distribution was peaceful and non-disruptive.

Conclusion: Affirming Managerial Authority with Caveats

The Supreme Court's decision in the M Office (Meguro Telegraph and Telephone Office) case affirmed a significant degree of managerial authority to regulate employee conduct within the workplace to maintain enterprise order. This includes the power to restrict political expression during working hours (based on a stringent interpretation of the duty of devotion to work) and to require prior permission for activities like leaflet distribution, even during break times, if such activities could reasonably be seen as disruptive. However, the Court also introduced the concept of "special circumstances," suggesting that formally prohibited conduct might not be disciplinable if it poses no genuine threat to workplace order. While upholding the specific disciplinary action in this instance, the judgment, with its nuanced exceptions, set the stage for ongoing judicial balancing of employer interests in order and employee rights to expression and association within the workplace.