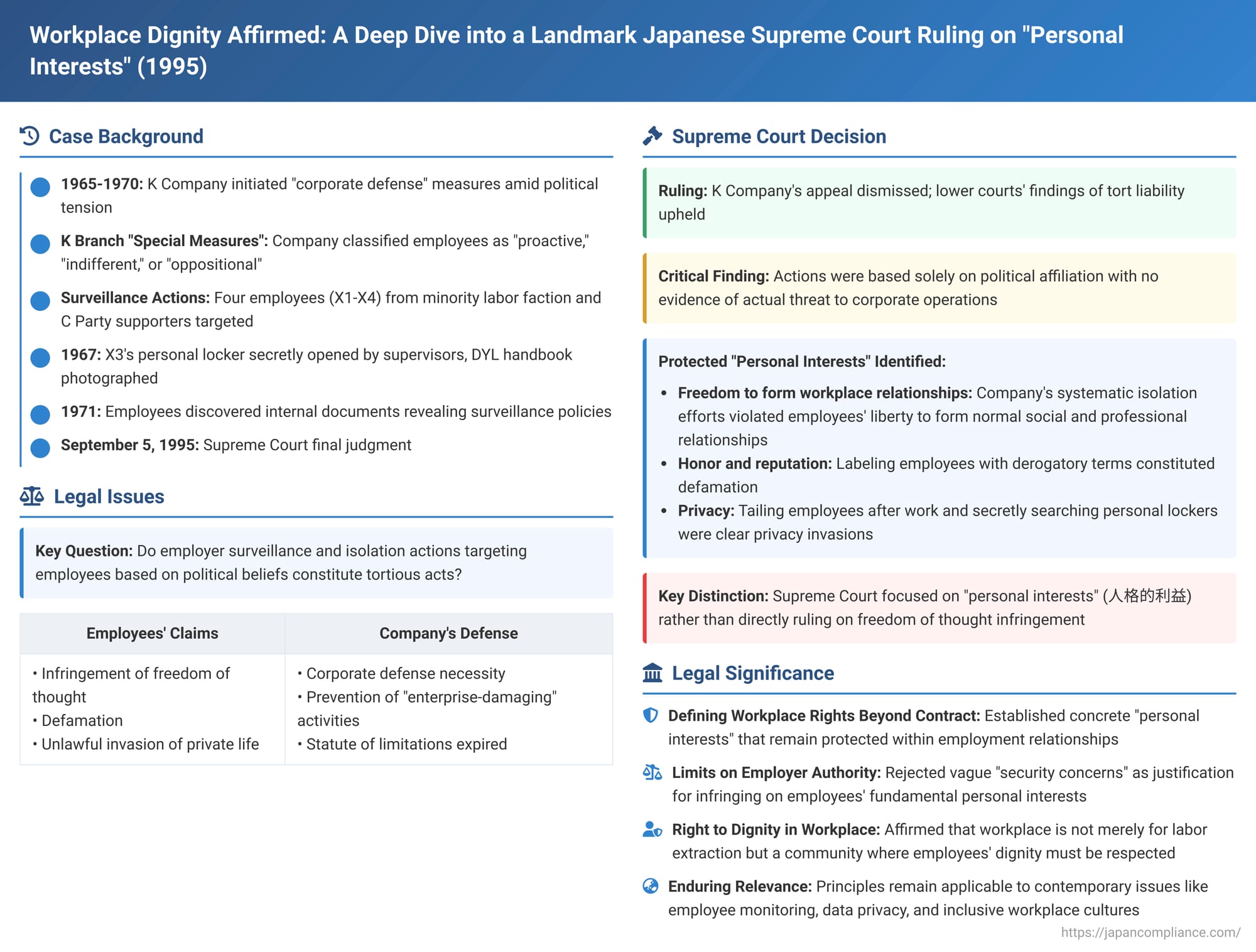

Workplace Dignity Affirmed: A Deep Dive into a Landmark Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on "Personal Interests"

The employment relationship is often viewed primarily through the lens of contractual obligations—work performed for wages. However, the workplace is also a social environment where individuals spend a significant portion of their lives. This raises crucial questions about the extent to which employers must respect employees' broader "personal interests" or "personality rights." A landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on September 5, 1995, in what we will refer to as the K Company case, brought these issues into sharp focus, delivering a significant judgment on corporate overreach and the protection of employee dignity.

The Seeds of Conflict: Background of the K Company Case

The plaintiffs in this case were four employees of K Company, a major electric power utility in Japan, whom we will call X1, X2, X3, and X4. All were members of the A Labor Union, which represented K Company's employees. Within this union, X1-X4 belonged to a minority faction that opposed the mainstream leadership's cooperative stance with company management. They were also known to be members of, or sympathizers with, the C Party.

The events unfolded against a backdrop of heightened social and political tension in Japan, particularly from around 1965 leading up to the 1970 revision of the US-Japan Security Treaty. K Company, anticipating potential disruptions and "enterprise-damaging activities" similar to those experienced during the 1960 Security Treaty protests, initiated comprehensive "corporate defense" measures. A core part of this strategy involved classifying employees into three categories concerning their stance on corporate defense: "proactive," "indifferent," and "oppositional." The company specifically identified "oppositional" employees as those who might leak confidential information. The strategy involved educating "indifferent" employees while intensifying the identification and monitoring of "oppositional" elements and gathering "subversive information."

Within K Company's K Branch, these policies were implemented under the guise of "Special Measures." X1, X2, X3, X4, and other members of their left-leaning group were designated as "unsound elements." The company then systematically engaged in actions designed to monitor, investigate, isolate, and ultimately exclude them. These actions included:

- Constant Surveillance: Superiors were instructed to closely monitor the movements and activities of X1-X4.

- Tailing After Work: Employees X2 and X3 were followed by company personnel after they left work.

- Requests to Police: The company reportedly sought information about X1-X4 from the police.

- Orchestrated Isolation: Management actively worked to prevent other employees from interacting with X1-X4, urging colleagues to avoid contact with them.

- Exclusion from Activities: X1-X4 were deliberately excluded from company-sponsored cultural and sports events.

- The Locker Incident: Around 1967, a particularly invasive act occurred involving X3. Based on a report from individuals monitoring him, X3’s superiors, including the general affairs section chief, secretly opened his personal locker at work. They removed a "DYL handbook" (Democratic Youth League handbook) from the pocket of X3’s jacket and photographed its contents.

Around 1971, X1-X4 came into possession of internal K Company documents that revealed the extent of the surveillance, tailing, and isolation policies directed against them. Alleging that these actions constituted an infringement of their freedom of thought, defamation, and an unlawful invasion of their personal lives, they filed a lawsuit against K Company seeking monetary damages for the harm caused and a public apology.

The district court found in favor of the employees, stating that K Company's actions had infringed their freedom of thought and belief, obstructed the formation of free human relationships in the workplace, defamed them, and lowered their personal evaluation. The High Court largely upheld this decision, adding that while not all acts were direct infringements on freedom of thought (like forcing ideological conversion), they indirectly coerced conversion by creating a hostile environment. The High Court also explicitly found that the company's surveillance and information gathering exceeded permissible limits of an employer's supervisory rights and infringed the employees' human rights and privacy. K Company appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Pronouncement (September 5, 1995)

The Supreme Court of Japan dismissed K Company's appeal, affirming the lower courts' rulings that held the company liable for its actions. The Court's reasoning provided crucial clarification on the protection of employees' personal interests in the workplace.

The Court meticulously reviewed the facts established by the lower courts. It emphasized a critical finding: K Company's actions against X1-X4 were undertaken solely because they were members of or sympathizers with the C Party, and not because there was any concrete evidence suggesting they posed an actual threat of disrupting corporate order or causing operational chaos.

The Supreme Court identified several specific ways in which K Company's conduct had harmed the employees:

- Infringement of the Freedom to Form Free Human Relationships in the Workplace: The company, through its management structure, continuously monitored X1-X4 both inside and outside the workplace. It actively denigrated their ideological positions, labeling them as "extreme leftist elements" or "uncooperative with management policy," and systematically pressured other employees to shun them. These concerted efforts to isolate X1-X4 were deemed an unjust infringement of their liberty to form normal social and professional relationships within the work environment.

- Defamation of Honor: The act of labeling the employees with derogatory terms based on their beliefs and disseminating these views to other employees constituted an attack on their reputation and honor.

- Infringement of Privacy: The tailing of employees X2 and X3 after work was a clear invasion of their private lives. The most egregious act of privacy infringement was the clandestine opening of X3's locker and the photographing of his private "DYL handbook." The Court indicated that the pervasive surveillance also contributed to privacy violations.

The Supreme Court concluded that this series of actions, driven by K Company's official policy, collectively infringed upon the "personal interests" (jinkakuteki rieki – 人格的利益) of X1, X2, X3, and X4. As these actions were orchestrated at a company level, they constituted distinct tortious acts by K Company against each of the affected employees.

The Court also summarily dismissed K Company's procedural arguments concerning the admissibility of certain documents as evidence and the statute of limitations for the claims. It upheld the High Court's finding that the employees became aware of the harm and the perpetrator (K Company) in 1971 upon reviewing a specific internal report, meaning their lawsuit was filed within the permissible time frame.

Analysis and Enduring Implications

The K Company case is a landmark in Japanese labor law, not only for its outcome but also for the principles it articulated regarding the protection of employee dignity and personal space within the corporate structure.

Defining "Personal Interests" in the Workplace:

A key significance of the judgment is the Supreme Court's concrete identification of specific "personal interests" that are legally protected within the employment relationship. These include:

- The freedom to form and maintain normal human relationships in the workplace.

- An individual's honor and reputation.

- Personal privacy.

This went beyond merely economic aspects of employment, affirming that employees retain fundamental personal rights that employers must respect.

"Personal Interests" vs. "Personality Rights" (Jinkakuken):

The judgment predominantly uses the term "personal interests" (jinkakuteki rieki). Broader Japanese legal discourse, particularly in academia and subsequent case law, often employs the concept of "personality rights" (jinkakuken – 人格権), which encompasses a wide array of non-property rights essential to an individual's existence and dignity (e.g., rights relating to life, body, liberty, honor, privacy, likeness). While the terminology differs slightly, the "personal interests" protected in the K Company case are effectively components of these broader personality rights. For the purpose of claiming damages in tort, the distinction is largely semantic, as infringement of these core interests forms the basis of a claim.

The Nuance on Freedom of Thought and Belief:

Interestingly, the Supreme Court, unlike the lower courts, did not explicitly anchor its finding of a tort in the direct infringement of the employees' "freedom of thought and belief." This cautious approach may stem from several factors. There were no overt acts of coercion, such as forcing the employees to renounce their beliefs. Furthermore, the employees were largely unaware of the full extent of K Company's surveillance and isolation tactics while these measures were actively being implemented. Judicial precedent, such as the earlier Tokyo Electric Power Shioyama Office case (Supreme Court, 1988), had also shown a degree of restraint in finding an illegal infringement of mental freedom where an employee was questioned about C Party membership but not directly coerced.

However, the absence of a direct finding on "freedom of thought" infringement does not diminish the ruling's impact. The company's motive—targeting the employees solely due to their political affiliations—was a crucial element in demonstrating the unjust nature of its actions. The Court found that actions driven by ideological animus, which then manifested as concrete infringements upon other personal interests like workplace social freedom, honor, and privacy, were indeed tortious. The ideological targeting made the company's purported justifications (like "corporate defense") hollow, as there was no actual threat posed by the employees.

Limits on Employer Justification and Control:

The K Company case powerfully illustrates that an employer's managerial prerogatives are not absolute. The company's "corporate defense" rationale was effectively dismissed because its actions were disproportionate and not based on any tangible risk posed by the targeted employees. This implies that employers cannot use vague security concerns as a pretext for infringing upon employees' fundamental personal interests, especially when such actions are rooted in discrimination based on political belief or affiliation. The ruling inherently questions the legitimacy of excessive employee monitoring and control, particularly when it extends to employees' private lives or associations that have no demonstrable bearing on their job performance or genuine corporate security.

The Right to a Dignified Workplace Environment:

This judgment supports the principle that employees are entitled to a workplace environment that respects their dignity. This means more than just safe physical conditions; it encompasses an atmosphere free from employer-orchestrated surveillance targeting personal beliefs, induced social isolation, and attacks on personal honor. The workplace is recognized not merely as a site for labor extraction but as a community where individuals have a right to exist with respect.

Contemporary Relevance:

Although the K Company case arose from a specific socio-political context of Cold War-era ideological conflict, its principles resonate strongly with contemporary workplace issues. Concerns about employee monitoring through technology, data privacy in the digital age, the impact of political polarization on workplace relations, and the broader push for inclusive and respectful corporate cultures all find echoes in this ruling. The fundamental tenet—that employers must respect the personal dignity and core rights of their employees—remains a timeless and critical aspect of fair labor practices.

Conclusion

The K Company Supreme Court judgment of September 5, 1995, stands as a vital affirmation of employee rights in Japan. It underscores that the employment relationship does not grant employers license to unduly interfere with the "personal interests" of their workforce. By recognizing and protecting employees' freedom to form workplace relationships, their honor, and their privacy against ideologically motivated corporate actions, the Court sent a clear message: managerial authority must be exercised within lawful bounds that respect the fundamental dignity of every employee. This case continues to serve as a critical reminder that fostering a workplace grounded in respect for personal rights is not just an ethical imperative but a legal one.