Workforce Management in Japan: Tackling Indirect Discrimination and the New Freelance Act

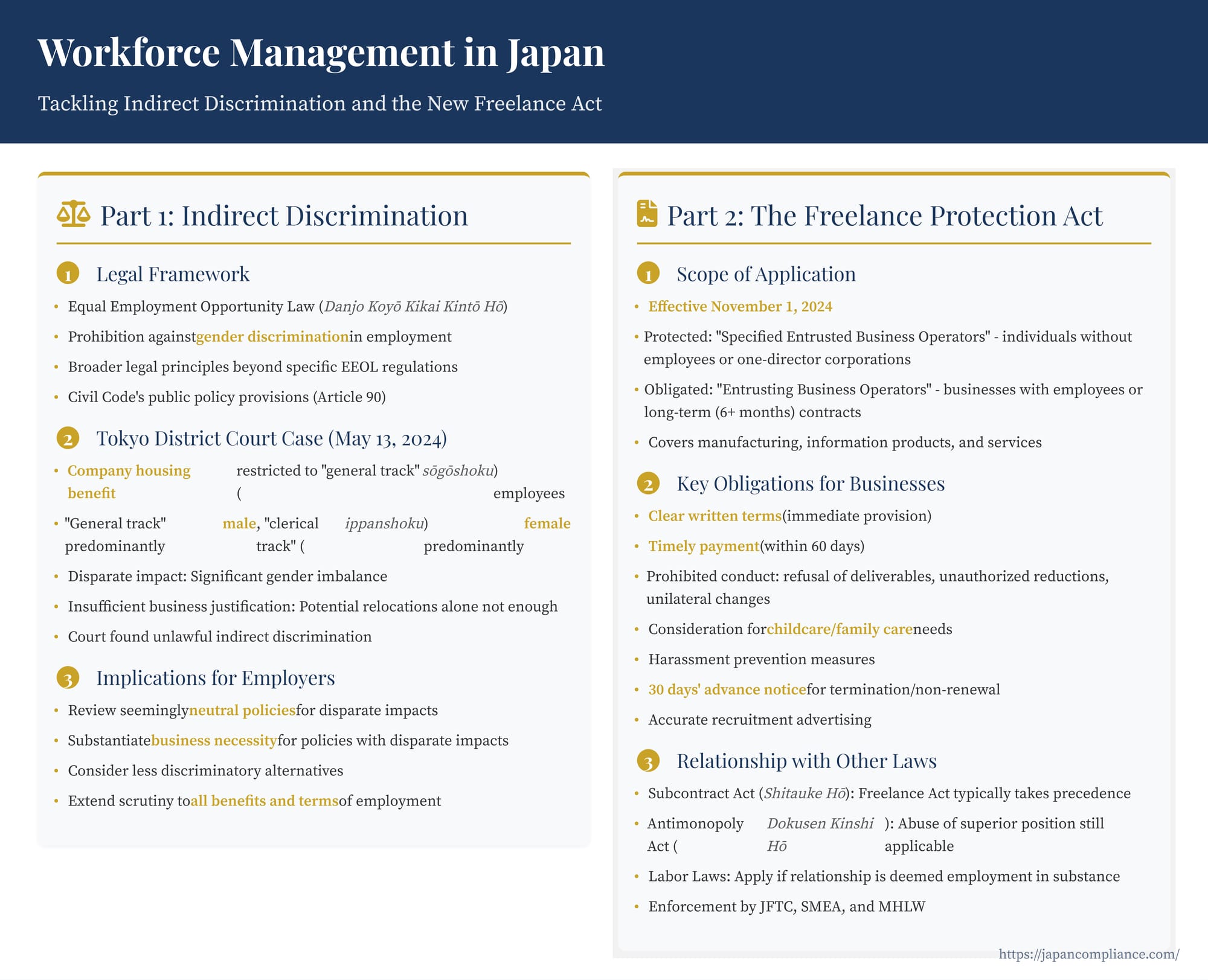

TL;DR: Japan is tightening rules on indirect discrimination while launching a Freelance Protection Act that mandates clear contracts, 60-day payment and anti-harassment duties. Employers must audit “neutral” policies for disparate impact and overhaul freelancer onboarding by November 2024.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Navigating Japan's Evolving Labor Landscape

- Part 1: Indirect Discrimination – Beyond Explicit Prohibitions

- Part 2: The Freelance Protection Act – New Rules for Engaging Independent Contractors

- Conclusion: Ensuring Fairness Across the Workforce

Introduction: Navigating Japan's Evolving Labor Landscape

For foreign companies operating in Japan, managing workforce relationships effectively requires navigating a legal landscape with unique features and ongoing developments. Beyond standard employment contracts, two areas demanding increasing attention are the potential for indirect discrimination in workplace policies and the new regulations governing the engagement of freelance or independent contractors.

Recent court decisions are shedding light on how seemingly neutral employment practices can be challenged as discriminatory if they disproportionately disadvantage certain groups without sufficient justification. Simultaneously, Japan has introduced the Act on the Optimization of Transactions for Specified Entrusted Business Operators (commonly known as the Freelance Protection Act), which establishes a new set of rules aimed at ensuring fair treatment for independent contractors. This Act came into full effect on November 1, 2024.

Understanding these developments is critical for businesses seeking to maintain compliant, fair, and effective workforce management strategies in Japan. This article explores the nuances of indirect discrimination risk and unpacks the key requirements of the new Freelance Protection Act, offering insights for legal and business professionals.

Part 1: Indirect Discrimination – Beyond Explicit Prohibitions

Japan's Act on Securing, Etc. of Equal Opportunity and Treatment between Men and Women in Employment (男女雇用機会均等法, Danjo Koyō Kikai Kintō Hō, commonly abbreviated as EEOL) prohibits gender discrimination in various aspects of employment, including recruitment, assignment, promotion, benefits, and retirement. While direct discrimination is clearly outlawed, the concept of indirect discrimination presents more subtle challenges.

The Legal Framework for Indirect Discrimination

The EEOL framework distinguishes between:

- Direct Discrimination: Treating someone less favorably explicitly because of their gender.

- Indirect Discrimination: Applying a seemingly neutral policy, criterion, or practice that disproportionately disadvantages individuals of a particular gender, and which cannot be justified by objective factors unrelated to gender.

The EEOL regulations specify certain practices presumed to be indirect discrimination unless objectively justified (e.g., height/weight requirements for recruitment unrelated to job duties, requirements for accepting nationwide transfers for promotion in certain roles).

However, a crucial point highlighted by recent case law and supported by Diet resolutions and administrative circulars is that practices not explicitly listed in the EEOL regulations can still constitute unlawful indirect discrimination under broader legal principles. If a company policy or practice, though neutral on its face, creates a significant disparate impact based on gender (or potentially other protected characteristics) and lacks a compelling, objective business justification, it could be deemed unlawful under the Civil Code's public policy provisions (Article 90) or as a tort (unlawful act).

Case Study: Company Housing and Job Tracks (Tokyo District Court, May 13, 2024)

A significant ruling from the Tokyo District Court (Reiwa 2 (Wa) No. 20432) illustrates this principle in action.

- Background: A company ("Company Y") offered a valuable company housing benefit (significantly subsidized rent). Eligibility for this benefit was formally restricted to employees on the "general track" (総合職, sōgōshoku). The defining characteristic of this track, according to company rules, was the employees' eligibility and potential obligation to accept nationwide relocations (配転, haiten). In contrast, employees on the "clerical track" (一般職, ippanshoku) were not subject to relocation and were ineligible for the housing benefit. Demographically, the vast majority of sōgōshoku employees at the company were male, while the majority of ippanshoku employees were female. A female employee on the ippanshoku track, who was denied the housing benefit, sued the company, alleging the policy amounted to unlawful gender discrimination. The company defended the policy, arguing that the distinction was justified by the business need associated with the potential relocation requirement for sōgōshoku employees.

- The Court's Analysis: The court first acknowledged that housing benefits are not among the practices explicitly defined as potentially indirect discrimination in the EEOL implementing regulations. However, it strongly affirmed the principle that practices constituting de facto indirect discrimination, even if not explicitly listed, can be challenged and found unlawful under general legal doctrines (public policy and tort law were considered).

The court then examined the policy's impact and justification:- Disparate Impact: Given the stark gender imbalance between the eligible (sōgōshoku) and ineligible (ippanshoku) tracks, the policy clearly had a disproportionately negative impact on female employees.

- Lack of Reasonable Justification: This was the critical point. The court scrutinized the company's asserted justification – the need to support employees who might be relocated. It found the justification insufficient because:

- The company's actual practice sometimes allowed sōgōshoku employees to receive the housing benefit even when relocation was not involved (e.g., upon marriage).

- The company did not adequately demonstrate that restricting the benefit exclusively to the sōgōshoku track was genuinely necessary for business operations, especially since a significant number of sōgōshoku employees had never actually experienced relocation. The potential for relocation alone was not deemed a strong enough reason to justify the significant disparity in benefits.

- The economic value of the housing benefit was substantial, making the disparity significant.

- Conclusion: Based on the disproportionate impact on female employees and the lack of a convincing business necessity for the distinction, the court concluded that the company's housing policy, as operated, constituted unlawful indirect discrimination. The company was found liable for damages under tort law.

Implications for Employers

This case serves as a potent reminder for employers in Japan, including foreign companies:

- Review Neutral Policies: Seemingly objective policies based on job categories, mobility requirements, compensation structures, or benefit eligibility criteria should be reviewed for potential disparate impacts on protected groups (primarily gender under the EEOL, but potentially others depending on context).

- Substantiate Business Necessity: If a policy creates a disparate impact, be prepared to demonstrate a strong, objective, and reasonably necessary business justification for the distinction. Courts will look beyond formal rules to actual operational practices and the genuineness of the justification.

- Consider Alternatives: Explore less discriminatory alternatives that can achieve the same legitimate business objectives.

- Benefits Matter: Discrimination risk extends beyond hiring and promotion to encompass all terms and conditions of employment, including benefits, allowances, and support systems.

Part 2: The Freelance Protection Act – New Rules for Engaging Independent Contractors

Reflecting the global rise of non-traditional work arrangements, Japan enacted the Act on the Optimization of Transactions for Specified Entrusted Business Operators (特定受託事業者に係る取引の適正化等に関する法律, tokutei jutaku jigyōsha ni kakaru torihiki no tekiseika tō ni kansuru hōritsu), which took full effect on November 1, 2024. This law aims to protect individuals working as freelancers or independent contractors by establishing minimum standards for their business dealings with clients.

Background and Purpose

The Act acknowledges the growing number of individuals choosing freelance work styles but recognizes their potential vulnerability due to disparities in negotiating power compared to client businesses. Its purpose is twofold: to ensure fair transactions (handled primarily by the Japan Fair Trade Commission and the Small and Medium Enterprise Agency) and to provide a stable working environment (handled primarily by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare). It achieves this by imposing specific obligations on businesses that commission work from freelancers.

Scope of Application

- Protected Individuals ("Specified Entrusted Business Operators"): The Act protects individuals who undertake work on consignment without employing others. It also covers corporations that have only one director (effectively sole-proprietor companies) and no employees (Article 2(1)). The term "employee" here generally refers to those meeting the criteria for employment insurance coverage (e.g., working 20+ hours/week and expected to be employed for 31+ days).

- Obligated Businesses ("Entrusting Business Operators"): The scope of obligations varies slightly depending on the nature of the client business:

- Basic Duty (Clear Terms - Art. 3): Any business operator (regardless of size or number of employees) that entrusts work to a protected freelancer must clearly specify the terms of the engagement.

- Enhanced Duties (Prohibited Conduct, Consideration, Notice - Arts. 5, 13, 16): These stricter obligations apply only to "Specified Entrusting Business Operators" (特定業務委託事業者, tokutei gyōmu itaku jigyōsha). This category includes:

- Business operators with employees that entrust work to protected freelancers.

- Business operators without employees that entrust work to protected freelancers only if the consignment is for a period of 6 months or longer (including renewals).

(Note: The advertising rules in Art. 12 and harassment prevention rules in Art. 14 also primarily target businesses with employees).

- Covered Work ("Business Consignment"): The Act covers a broad range of commissioned work (業務委託, gyōmu itaku), including the manufacturing or processing of goods, the creation of information products (e.g., software, content, designs), and the provision of services (Article 2(3)).

Key Obligations for Entrusting Businesses

- Clear Specification of Terms (Article 3): Upon commissioning work, the entrusting business must immediately provide the freelancer with clear, written (or electronic) details of the engagement. This includes:

- The content of the deliverables or services.

- The amount of remuneration (or a clear calculation method if the exact amount cannot be fixed).

- The payment date.

- Details regarding the transfer or licensing of any intellectual property rights created.

- Names or other identifiers of both parties.

- (Unlike the Subcontract Act, electronic provision does not require the freelancer's prior consent, though they can request paper copies later).

- Timely Payment (Article 4): Remuneration must be paid within 60 days of the freelancer delivering the goods or completing the service. A later payment date is permissible only if agreed upon and it aligns with the entrusting business's normal, established payment cycle for similar transactions. Failure to specify a date defaults the due date to the day of delivery/completion.

- Prohibited Conduct (Article 5 - for "Specified Entrusting Businesses," contracts ≥ 1 month): These businesses are prohibited from engaging in unfair practices mirroring those under the Subcontract Act:

- Refusing to receive deliverables without a reason attributable to the freelancer.

- Reducing agreed remuneration without a reason attributable to the freelancer.

- Returning deliverables without a reason attributable to the freelancer (unreasonable returns).

- Unfairly setting remuneration at a notably lower level than the market rate for similar work ("price beating").

- Coercing the freelancer to purchase goods or use services from the entrusting business or designated third parties without justification.

- Requesting the provision of economic benefits that unjustly harm the freelancer's interests.

- Unilaterally changing the scope of work or demanding re-dos without cause attributable to the freelancer, causing unfair harm.

- Consideration for Childcare/Family Care Needs (Article 13 - for "Specified Entrusting Businesses," contracts ≥ 6 months): If a long-term freelancer requests consideration due to needs related to pregnancy, childbirth, childcare, or family care, the entrusting business must make necessary efforts to accommodate them (e.g., adjusting schedules/deadlines, allowing remote work where feasible). This does not mandate granting every request but requires good-faith consideration and explanation if accommodation is not possible.

- Harassment Prevention Measures (Article 14 - primarily for businesses with employees): Entrusting businesses must take necessary measures to prevent harassment (power harassment, sexual harassment, etc.) directed towards freelancers by the business's own employees or executives. This includes establishing clear policies, providing consultation channels, and responding appropriately to incidents.

- Advance Notice for Termination/Non-Renewal (Article 16 - for "Specified Entrusting Businesses," contracts ≥ 6 months): For ongoing engagements lasting six months or more (including renewals), the entrusting business must provide the freelancer with at least 30 days' advance notice before terminating the contract mid-term or deciding not to renew it upon expiry. If requested by the freelancer, the reason for termination or non-renewal must also be disclosed. Exceptions apply if the termination is due to reasons attributable to the freelancer (e.g., serious breach).

- Accurate Recruitment Advertising (Article 12): When soliciting freelancers (e.g., through online platforms or advertisements), businesses must ensure the information provided about the work content, remuneration, conditions, etc., is accurate, up-to-date, and not misleading.

Relationship with Other Laws

The Freelance Protection Act operates alongside existing laws:

- Subcontract Act (下請法, Shitauke Hō): This act continues to apply to transactions meeting its criteria (based primarily on the capital size of the parties). Where both acts could potentially apply, the Freelance Protection Act generally takes precedence, although the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) retains discretion in certain overlapping situations.

- Antimonopoly Act (独占禁止法, Dokusen Kinshi Hō): Practices like abuse of superior bargaining position can still be addressed under the Antimonopoly Act.

- Labor Laws: If the actual working relationship is found to be one of employment (based on substance over form, considering factors like control and economic dependence), then standard labor laws (Labor Standards Act, etc.) apply instead of the Freelance Protection Act.

Implications for Businesses Using Freelancers

The Freelance Protection Act necessitates several adjustments for businesses engaging independent contractors in Japan:

- Formalization: Ad-hoc or purely verbal agreements are no longer sufficient. Clear, written (or properly electronic) specification of terms at the outset is mandatory.

- Process Review: Businesses need robust internal processes to:

- Issue compliant terms documentation promptly.

- Track delivery/completion dates and ensure payment within 60 days.

- Identify freelancers meeting the Act's definition (no employees).

- Determine if the business itself qualifies as a "Specified Entrusting Business Operator" for applying stricter rules (Arts. 5, 13, 16).

- Handle recruitment advertising accurately.

- Implement harassment prevention covering freelancers.

- Manage contract termination/non-renewal notice periods for longer engagements.

- Contract Content: Agreements should clearly define scope, deliverables, remuneration (including calculation methods and handling of expenses), IP rights, and payment terms. Businesses subject to Article 5 should ensure their practices avoid prohibited conduct.

- HR-like Functions: For longer-term freelancers, businesses need mechanisms to consider requests related to family care and provide harassment protection channels.

Conclusion: Ensuring Fairness Across the Workforce

Japan's focus on both indirect discrimination within traditional employment and fair treatment for the growing freelance workforce signals a move towards greater scrutiny of workplace practices and business relationships. For US companies operating in Japan, compliance requires attention to both fronts.

Reviewing internal policies and benefit structures through the lens of potential disparate impact is crucial to mitigate indirect discrimination risks. Simultaneously, implementing structured, transparent, and fair processes for engaging freelancers is now a legal requirement under the Freelance Protection Act. Adapting to these evolving standards will be key to managing legal risks, attracting talent, and maintaining positive workforce relations in the Japanese market.

- Mind the Gap: Wage Disparity Between Fixed-Term and Indefinite-Term Employees

- Freedom to Resign vs. Training-Cost Clawbacks in Japan

- Employee Dismissals in Japan: Membership vs. Job-Based Models

- Cabinet Secretariat — Overview of Freelance Protection Act (JP)

https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/seisaku/freelance_act_outline.html