Workers' Comp vs. Consolation Money: Japan's Supreme Court Separates Financial and Non-Financial Damages (December 1, 1966)

Japan’s Supreme Court (1966) held that consolation money for pain and suffering cannot reduce an employer’s statutory workers’ compensation, firmly separating financial and non‑financial damages.

TL;DR

In its 1966 decision, the Supreme Court of Japan ruled that “consolation money” (isharyō/mimaikin) paid by a third‑party tortfeasor compensates mental suffering, whereas statutory “disaster compensation” under the Labour Standards Act covers only financial losses such as medical costs and lost wages. Because the two address different types of harm, an employer cannot offset consolation money against its statutory payment obligations.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: An Accident, a Settlement, and a Compensation Claim

- Lower Court Ruling and the Appeal Issue

- Legal Framework: LSA Disaster Compensation and Isharyō

- The Supreme Court’s Analysis (December 1 1966): Distinguishing Damage Types

- Implications and Significance: Separating Financial and Non‑Financial Compensation

- Conclusion

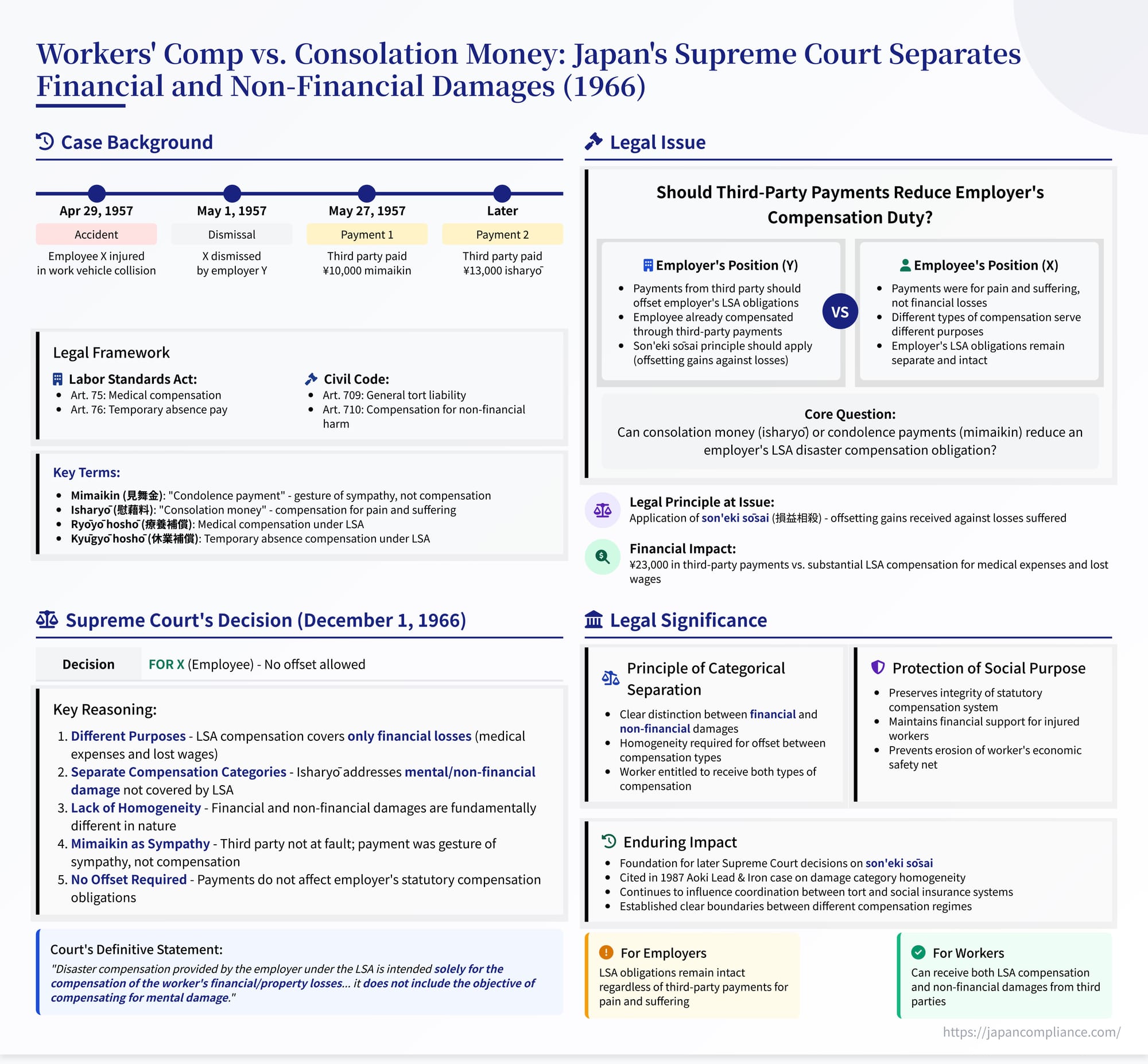

On December 1, 1966, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a judgment clarifying a fundamental principle in coordinating workplace accident compensation with third-party tort claims (Case No. 1963 (O) No. 1035, "Damages Claim Case"). The case addressed whether payments received by an injured worker from a third-party tortfeasor specifically designated as "consolation money" (isharyō - 慰藉料) or "condolence payment" (mimaikin - 見舞金) should reduce the amount of statutory disaster compensation the employer owes under the Labour Standards Act (LSA). The Court ruled that such payments, aimed at compensating for non-financial harm (pain and suffering) or made as a gesture of sympathy, are distinct in nature from the LSA's disaster compensation, which solely covers financial losses (medical expenses and lost wages). Therefore, these payments should not be deducted from the employer's statutory compensation obligations. This decision established an important early precedent distinguishing between different categories of harm and compensation in the context of workplace injuries caused by third parties.

Factual Background: An Accident, a Settlement, and a Compensation Claim

The case involved an employee injured while working and subsequent interactions with both the third party involved in the accident and the employer:

- The Accident: On April 29, 1957, X (the appellee), an employee of Company Y (the appellant), was driving a light vehicle in the course of his duties for Y. He was involved in a collision with a vehicle driven by A (Umemura), resulting in X suffering serious injuries, including a skull base fracture.

- Settlement with Third Party (A):

- Following the accident, X (or his representative) engaged with A. It was apparently determined (with police involvement) that A was not at fault for the accident. Nonetheless, on May 27, 1957, A paid X 10,000 yen as a "condolence payment" (mimaikin - 見舞金).

- Subsequently, through court-mediated conciliation (調停 - chōtei) at the Showa Summary Court, A paid X an additional 13,000 yen (the judgment notes a record discrepancy suggesting 15,000 yen, but recognizes 13,000 yen as the likely correct amount for consolation money). The Supreme Court found, based on the record, that this second payment was intended as "consolation money" (isharyō - 慰藉料) for pain and suffering.

- Dismissal and Claim Against Employer (Y): X was dismissed by Company Y on May 1, 1957 (shortly after the accident). X subsequently filed a lawsuit against Y. While initially based on tort damages, X later amended the claim (an amendment deemed permissible by the courts) to seek statutory disaster compensation directly from the employer under the Labour Standards Act (LSA). The specific claims relevant to the appeal were for:

- Medical Compensation (療養補償 - ryōyō hoshō): Reimbursement for medical expenses incurred (LSA Art. 75).

- Temporary Absence Compensation (休業補償 - kyūgyō hoshō): Compensation for lost wages during the period of inability to work (LSA Art. 76).

- Termination Compensation (打切補償 - uchikiri hoshō): A lump-sum payment sometimes allowed after 3 years of medical leave (LSA Art. 81) – this part was ultimately remanded on procedural grounds unrelated to the main issue here.

Lower Court Ruling and the Appeal Issue

The High Court (Nagoya High Court) largely ruled in favor of X, ordering Company Y to pay significant amounts for medical compensation and temporary absence compensation (plus delay damages). In calculating this amount, the High Court did not deduct the 10,000 yen mimaikin or the 13,000 yen isharyō that X had received from the third party, A.

Company Y appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing, among other points, that the High Court erred in failing to deduct these payments received from the third party from the LSA disaster compensation Y was ordered to pay. Y essentially argued that these payments constituted a benefit received by X due to the accident and should be offset against Y's compensation liability under the principles of son'eki sōsai (offsetting gains and losses) or similar coordination logic.

Legal Framework: LSA Disaster Compensation and Isharyō

The Labour Standards Act mandates employers provide compensation for work-related injuries or illnesses, regardless of employer fault. Key provisions include:

- LSA Art. 75: Employer's duty to provide necessary medical treatment or cover its cost (Medical Compensation).

- LSA Art. 76: Employer's duty to pay compensation for lost wages (at a certain percentage of average wages) during periods the worker cannot work due to medical treatment (Temporary Absence Compensation).

- Other provisions: Cover permanent disability, survivor benefits, and funeral expenses.

Separately, under general tort law (Civil Code Art. 709, 710), an injured party can claim damages from the tortfeasor, including:

- Financial Damages: Medical expenses, lost earnings, etc.

- Non-Financial Damages (慰謝料 - isharyō): Compensation for mental and physical pain and suffering.

The legal issue was whether payments explicitly designated as isharyō or similar non-compensatory payments like mimaikin from the tortfeasor should reduce the employer's distinct statutory obligation under the LSA to compensate for the financial losses covered by Articles 75 and 76.

The Supreme Court's Analysis (December 1, 1966): Distinguishing Damage Types

The Supreme Court rejected Company Y's argument regarding the offset and affirmed the High Court's decision not to deduct the payments received from the third party.

1. Regarding the "Condolence Payment" (Mimaikin):

The Court quickly dismissed the argument for deducting the 10,000 yen. It noted that Y itself had characterized this payment as a mimaikin given after the third party A was found not at fault. Such payments are generally considered gestures of sympathy rather than compensation for legally recognized damages. Therefore, it was "obvious" (akiraka) that this amount should not be deducted from the statutory disaster compensation.

2. Regarding the "Consolation Money" (Isharyō):

The Court focused on the 13,000 yen payment received through court mediation, which it found was clearly intended as isharyō. The core of its reasoning rested on the fundamental difference between the purpose of LSA disaster compensation and the purpose of isharyō:

- Purpose of LSA Disaster Compensation: The Court explicitly stated that disaster compensation provided by the employer under the LSA is intended "solely for the compensation of the worker's financial/property losses" (rōdōsha no kōmutsuta zaisan-jō no songai no tenpo no tame ni nomi nasareru). This includes medical expenses (Art. 75) and lost wages (Art. 76).

- Purpose of Isharyō: In contrast, isharyō under tort law is compensation for "mental damage" or non-financial harm – the pain, suffering, and emotional distress caused by the injury. LSA disaster compensation "does not include the objective of compensating for mental damage." (seishinteki songai no tenpo no mokuteki o mo fukumu mono de wa nai).

- Lack of Homogeneity: Because LSA disaster compensation addresses financial losses and isharyō addresses non-financial losses, they cover different types of harm and serve distinct purposes. They lack the necessary "homogeneity" (dōshitsusei) for the principle of offsetting gains against losses to apply between them.

- No Offset: Therefore, the Court concluded, "consolation money paid by a third-party tortfeasor does not affect the amount of disaster compensation the employer should pay." The High Court was correct in ordering Y to pay the full statutory compensation amounts without deducting the isharyō X received from A.

3. Conclusion on Offset:

The Court found Y's arguments regarding the offset to be without merit. (The remainder of the judgment dealt with procedural issues and the separate claim for termination compensation under LSA Art. 81, ultimately remanding that specific part of the claim for reconsideration on whether it was properly pleaded and whether the conditions for it were met, which is outside the scope of the offset issue).

Implications and Significance: Separating Financial and Non-Financial Compensation

This 1966 Supreme Court decision established a clear and enduring principle in Japanese law regarding the coordination of compensation following workplace accidents involving third parties:

- Distinct Nature of Compensation: It firmly differentiates between statutory disaster compensation under the LSA (focused on tangible financial losses like medical costs and lost wages) and tort damages for pain and suffering (isharyō).

- No Offset for Isharyō against LSA Compensation: Payments specifically designated as isharyō (or similar payments like mimaikin not intended as damages compensation) received from a third-party tortfeasor cannot be used to reduce the employer's separate statutory obligation to provide LSA disaster compensation for the employee's financial losses.

- Protecting Different Interests: This ensures that the compensation intended for the victim's pain and suffering is not eroded by payments meant to cover economic necessities like medical care or wage replacement, preserving the distinct functions of each type of compensation.

- Foundation for Later Son'eki Sōsai Rulings: Although this case dealt with the employer's direct LSA duty, the principle of requiring homogeneity between the benefit/gain and the specific damage item before allowing an offset became a foundational element in later Supreme Court cases analyzing son'eki sōsai in the context of WCAI benefits and other social insurance payments versus various heads of tort damages (e.g., the Showa 62 [1987] Aoki Lead & Iron decision, analyzed previously, explicitly cited this 1966 case).

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's December 1, 1966, judgment clarified that under Japan's Labour Standards Act, the disaster compensation mandated for employers (covering medical costs and lost wages) serves solely to address the employee's financial losses arising from a work-related injury. Payments received by the employee from a third-party tortfeasor specifically as "consolation money" (isharyō) for pain and suffering, or as "condolence money" (mimaikin), target non-financial harm or are gestures of sympathy. Due to this fundamental difference in nature and purpose, such payments cannot be offset against, or reduce, the employer's distinct statutory obligation to provide financial disaster compensation under the LSA. This ruling established an important distinction between compensating for economic versus non-economic harm in the context of workplace injuries

- When a Lie Becomes a Crime: Japan’s Landmark Case on Lying for an Arrested Friend

- The Scapegoat Gambit: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Aiding an Arrested Criminal’s Escape

- Memory vs. Truth: How Japan’s High Court Defined Perjury Over a Century Ago

- Labour Standards Bureau – Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare