1963 Supreme Court Ruling: Can Japan’s Government Subrogate WCAI Claims After a Worker Settlement?

Japan’s 1963 Supreme Court held that a worker’s pre‑benefit settlement prevents the Government from subrogating WCAI claims, clarifying how private waivers affect public insurance rights.

TL;DR

A worker’s pre‑benefit settlement and express waiver of tort claims bars the Japanese Government from later exercising its statutory subrogation right under the Workers’ Accident Compensation Insurance Act (WCAI).

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: An Accident, a Settlement, and a Government Claim

- Lower Court Rulings: Conflicting Views on Settlement's Effect

- Legal Framework: WCAI Subrogation and Adjustment

- The Supreme Court's Analysis (June 4, 1963): Primacy of Private Settlement

- Implications and Significance: Worker Autonomy vs. Government Rights

- Conclusion

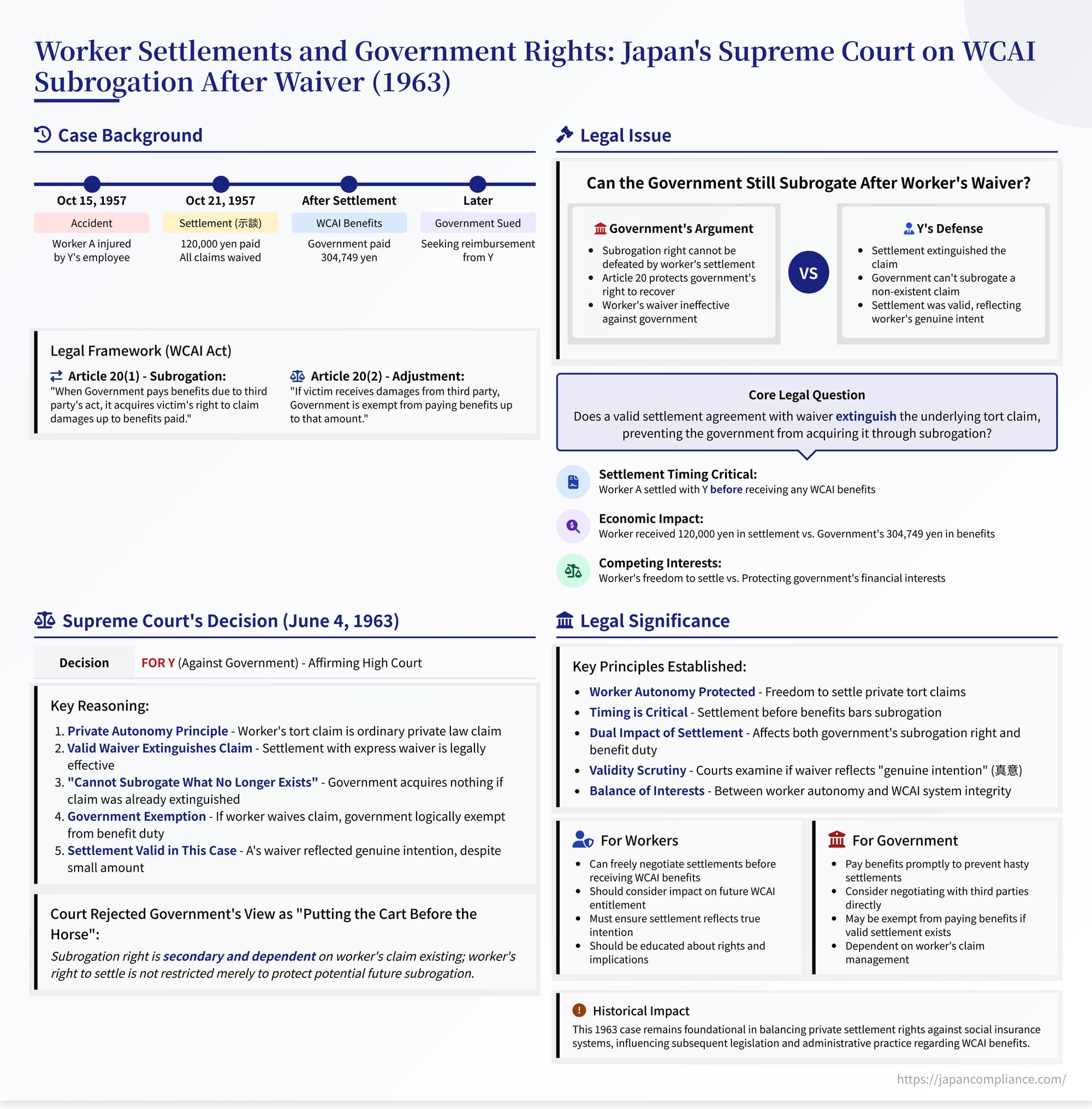

On June 4, 1963, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued a foundational judgment addressing the interplay between an injured worker's private settlement with a third-party tortfeasor and the government's rights under the Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act (WCAI Act, or Rōsai Hoken Hō - 労災保険法) (Case No. 1962 (O) No. 711, "Damages Claim Case"). The case explored whether the government could still exercise its statutory right of subrogation to recover WCAI benefits paid to a worker, even after the worker had previously settled with the tortfeasor and waived further claims before receiving those benefits. The Court concluded that a valid settlement and waiver by the worker extinguishes the underlying tort claim, thereby preventing the government from later acquiring that claim through subrogation. This early ruling established the principle that a worker's disposition of their private tort claim can directly impact the government's subsequent rights and obligations under the WCAI system.

Factual Background: An Accident, a Settlement, and a Government Claim

The sequence of events leading to the legal dispute was as follows:

- The Accident: On October 15, 1957, Worker A, an employee of a transport company (which was enrolled in WCAI), was injured in the course of employment when struck by a truck driven by K. K was employed by Y (O Transport, the appellee), and the accident occurred due to K's negligence while performing duties for Y. A suffered significant injuries, including a complex femur fracture.

- The Settlement (Jidan): Before A received any WCAI benefits, a settlement agreement (jidan - 示談) was reached on October 21, 1957, between A's agent (S) and Y (the employer of the tortfeasor driver). Under the terms of the settlement:

- A received payments totaling 120,000 yen (100,000 yen from automobile liability insurance under the precursor to modern CALI, plus an additional 20,000 yen from Y for consolation money, medical fees, etc.).

- In exchange, A agreed to be satisfied with these amounts and explicitly "waived all other claims for damages" (sono yo no baishō seikyūken issai o hōki suru) against Y.

- A was informed of the settlement terms by his agent S and approved them.

- WCAI Benefit Payment: Sometime after this settlement was concluded, the Hachinohe Labour Standards Inspection Office (acting for the government, appellant X) paid WCAI benefits to A totaling 304,749 yen. Notably, the LSIO official was shown the settlement agreement before making the payment but proceeded based on an internal view that the government was still obligated to pay benefits minus the settlement amount received by A.

- Government's Subrogation Lawsuit: Having paid the WCAI benefits, the government (X) then sued Y (the tortfeasor's employer) seeking reimbursement of the 304,749 yen paid. The government based its claim on its statutory right of subrogation under WCAI Act Article 20, Paragraph 1 (the predecessor to the current Article 12-4, Paragraph 1), which allows the government to acquire the worker's damages claim against a third party to the extent of benefits paid.

Lower Court Rulings: Conflicting Views on Settlement's Effect

The lower courts reached different conclusions:

- First Instance: Ruled in favor of the government, allowing the subrogation claim.

- Second Instance (Sendai High Court): Reversed the first instance decision and ruled against the government. The High Court held that the settlement agreement, including the waiver of further claims by A, was a valid private law act. This waiver effectively extinguished A's remaining tort claim against Y before the government paid any WCAI benefits. Since the claim no longer existed when the government made its payment, there was nothing for the government to acquire through subrogation under Article 20(1).

The government appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

Legal Framework: WCAI Subrogation and Adjustment

The case revolved around the interpretation of WCAI Act Article 20 (now Article 12-4) which governs the relationship between WCAI benefits and third-party tort claims:

- Article 20, Paragraph 1 (Subrogation): "In cases where the Government has paid insurance benefits due to an accident caused by the act of a third party, it shall acquire the right to claim damages held by the person who has received the benefits against the third party, up to the limit of the value of the benefits paid." (政府は...保険給付をしたときは、その給付の価額の限度で、補償を受けた者が第三者に対して有する損害賠償請求権を取得する。)

- Article 20, Paragraph 2 (Benefit Adjustment): "In the case referred to in the preceding paragraph, if the person entitled to receive compensation has received damages from the third party due to the same cause/event, the Government shall be exempted from its obligation for accident compensation up to the limit of the value thereof." (前項の場合において、補償を受けるべきものが、当該第三者より同一の事由につき損害賠償を受けたときは、政府は、その価額の限度で災害補償の義務を免れる。)

The key questions were: (1) Does a worker's waiver of damages (not just actual receipt) trigger the government's exemption under the principle behind Paragraph 2? (2) Does such a prior waiver prevent the government's subrogation right under Paragraph 1 from arising?

The Supreme Court's Analysis (June 4, 1963): Primacy of Private Settlement

The Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's decision, ruling against the government and establishing important principles regarding the effect of settlements on WCAI rights.

1. Nature of Worker's Tort Claim:

The Court first emphasized that the injured worker's claim against the third-party tortfeasor is an ordinary private law tort claim. The fact that the injury is also covered by WCAI does not alter the fundamental legal nature of this claim against the third party.

2. Worker's Freedom to Settle (Private Autonomy):

Based on the principle of private autonomy (shihō jichi no gensoku), which underpins Japanese private law, the injured worker (or their representative) generally possesses the freedom to settle their claim with the third party and to waive (免除 - menjo) all or part of the damages claim, unless a specific statute dictates otherwise.

3. Effect of Waiver on Government's Benefit Obligation (Interpreting Art. 20(2)):

The Court acknowledged that Article 20(2) only explicitly mentions the government's exemption from paying benefits when the worker actually receives damages. However, it reasoned beyond the literal text:

- Purpose of WCAI: The fundamental purpose of the WCAI system is to compensate the worker for the loss they suffered.

- Implicit Exemption via Waiver: If the worker voluntarily chooses to waive their right to recover damages from the responsible third party, thereby extinguishing their own claim to that extent, it follows "as a matter of course" (tōzen no koto) that the government should also be exempted from its obligation to pay WCAI benefits corresponding to the waived amount. The law does not need an explicit provision for this; it flows logically from the system's compensatory purpose. Why should the government pay benefits to compensate for a loss that the worker themselves chose not to recover from the party who caused it?

- Article 20(2) Doesn't Negate This: The Court stated that Article 20(2) merely clarifies the situation when damages are received and should not be interpreted as denying the government's exemption when the claim is validly waived instead.

4. Effect of Waiver on Government's Subrogation Right (Art. 20(1)):

The conclusion regarding subrogation followed directly:

- Subrogation Requires Existing Claim: The government's right to subrogate under Article 20(1) is premised on the worker having an existing damages claim against the third party at the time the government pays benefits. The government steps into the worker's shoes.

- Waiver Extinguishes Claim: A valid settlement and waiver by the worker extinguishes that claim (to the extent waived).

- No Claim, No Subrogation: Therefore, if the government pays benefits after the worker has validly waived the corresponding claim against the third party, "there is clearly no room for the statutory right of subrogation... to arise," because the prerequisite claim no longer exists.

5. Rejection of Government's "Protect Subrogation" Argument:

The government had argued, essentially, that the worker's waiver should be ineffective against the government because it would impair the government's potential future subrogation right. The Supreme Court forcefully rejected this:

- It called the argument "putting the cart before the horse" (honmatsu tentō no ron) and based on a misunderstanding of both tort claims and the nature of WCAI.

- The government's subrogation right is secondary and dependent on the worker's primary claim existing; the system is not designed such that the worker's right to settle their own claim is restricted merely to protect the government's potential future subrogation.

6. Addressing Potential Harm to Workers:

The Court acknowledged a potential downside: workers might enter into disadvantageous settlements ("careless" or "not truly intended") and, under the Court's interpretation, lose their right to WCAI benefits as a result, potentially undermining the WCAI system's goal of swift and fair protection. However, the Court suggested this risk could be managed through:

- Worker Education: Increasing workers' understanding of the WCAI system and the implications of settlements.

- Prompt WCAI Payments: Ensuring the government pays WCAI benefits quickly, reducing the pressure on workers to accept quick, low settlements from third parties.

- Strict Scrutiny of Settlements: Courts should rigorously examine whether a waiver of damages truly reflected the worker's "genuine intention" (shin'i) and was free from defects like mistake or fraud (sakugo mata wa sagi).

7. Application to the Case:

Applying these principles to the facts, the Court found:

- The settlement between A's agent and Y, including the waiver of further claims, was concluded before any WCAI benefits were paid.

- A was informed and approved the settlement.

- Although the settlement amount (20,000 yen beyond insurance) seemed "somewhat small," the Court found no grounds to invalidate the settlement or conclude that the waiver was not based on A's "genuine intention."

- Therefore, the settlement validly extinguished A's remaining damages claim against Y.

- Consequently, when the government later paid WCAI benefits, it acquired no subrogation right against Y.

The High Court's decision dismissing the government's claim was thus affirmed as correct.

Implications and Significance: Worker Autonomy vs. Government Rights

This 1963 Supreme Court decision established fundamental principles governing the interaction between WCAI benefits and third-party tort claims that remain relevant today:

- Primacy of Worker's Settlement Right: It confirms that an injured worker generally retains the autonomy to settle their private tort claim with a third-party tortfeasor, including waiving future claims, even if they are also potentially eligible for WCAI benefits.

- Settlement Before Benefits Can Bar Subrogation: A valid settlement and waiver concluded before WCAI benefits are paid extinguishes the underlying tort claim, preventing the government from subsequently exercising its statutory subrogation right under WCAI Act Art. 12-4(1).

- Settlement Likely Reduces Government's Benefit Duty: The Court strongly implied that if a worker validly waives a portion of their damages claim against a third party, the government's obligation to pay WCAI benefits is correspondingly reduced by that waived amount, based on the principle that WCAI compensates for actual, uncompensated loss. (This aspect, though technically obiter dictum, heavily influenced subsequent administrative practice).

- Importance of Settlement Timing and Validity: The timing of the settlement relative to the payment of WCAI benefits is critical. Furthermore, the validity of the settlement, particularly whether the waiver reflects the worker's true and informed intention, is subject to scrutiny. Settlements deemed invalid (e.g., due to mistake, duress, fraud, or perhaps being unconscionably low in certain circumstances) would likely not preclude government subrogation or benefit payment.

- Balancing Interests: The decision reflects a balancing act between respecting the worker's private autonomy to manage their tort claim and protecting the financial integrity of the WCAI system (by preventing double recovery and enabling government subrogation where possible). The Court tilted towards worker autonomy regarding the settlement itself, but linked that autonomy to the scope of subsequent WCAI entitlement.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's June 4, 1963, judgment clarified that an injured worker's settlement with a third-party tortfeasor, if validly concluded before Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance benefits are paid, effectively extinguishes the worker's tort claim to the extent of the settlement or waiver. This prior extinguishment prevents the government from later acquiring the claim through statutory subrogation under the WCAI Act after paying benefits. The decision underscores the principle of private autonomy in settling tort claims but also implicitly links the consequences of such settlements to the scope of the government's subsequent obligations under the workers' compensation system. It remains a foundational case for understanding the complex coordination between tort liability and social insurance in Japan.

- Workers' Comp vs. Consolation Money: Japan’s Supreme Court Separates Financial and Non‑Financial Damages (1966)

- Indirect Victims in Japanese Tort Law: Implications for U.S. Businesses

- Modifying Final Judgments for Periodic Payments in Japan: How Are Court Fees Calculated?

- Workers’ Compensation — Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW)

- Industrial Accident Compensation Insurance System (MHLW English PDF)