Japan Supreme Court: Company‑Party Fatality Ruled Work‑Related (2016 Decision)

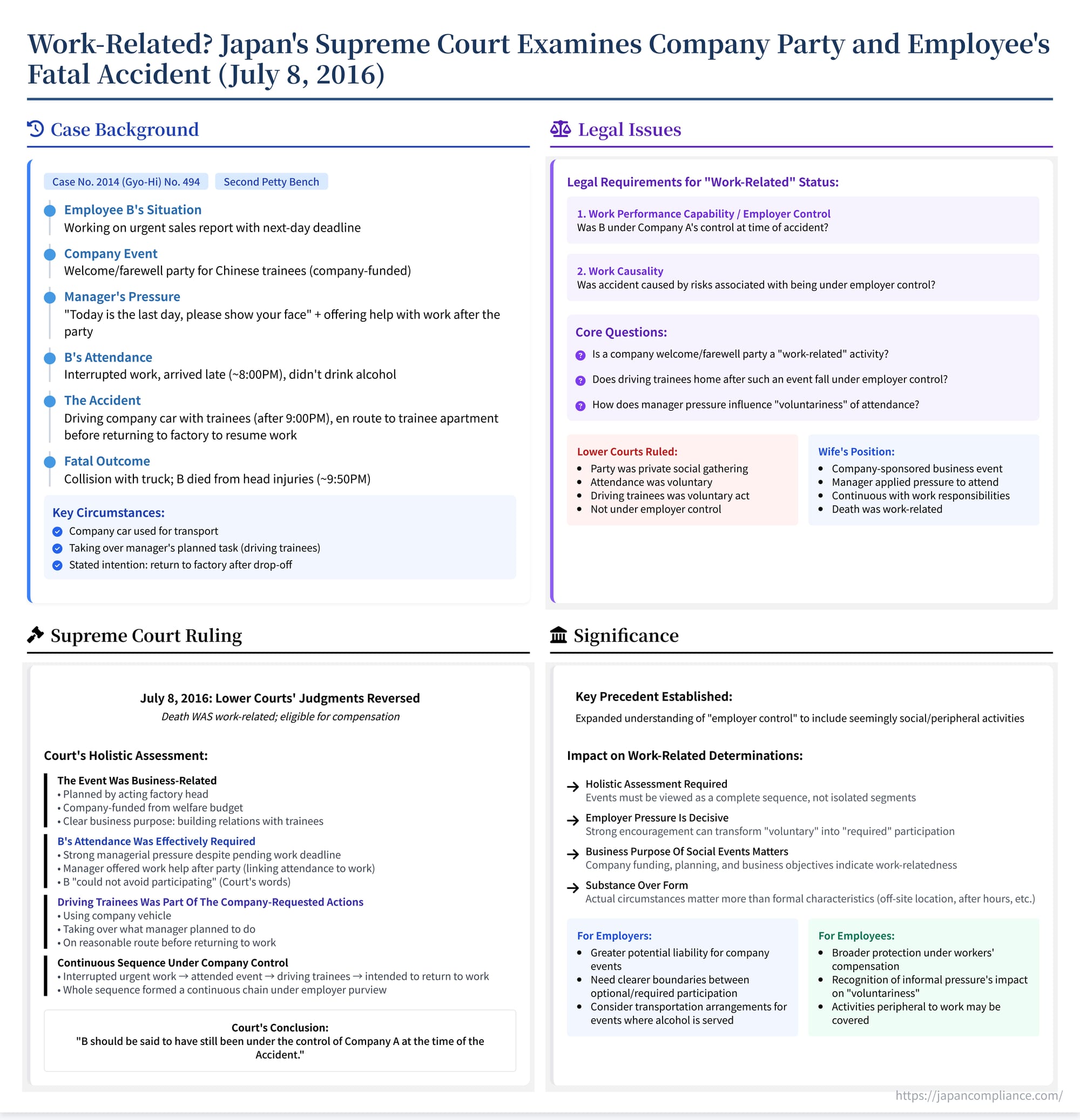

Japan’s Supreme Court ruled that a fatal after‑party car accident was work‑related, clarifying how employer pressure and business‑oriented social events affect workers’ compensation eligibility.

TL;DR

Japan’s Supreme Court (Second Petty Bench, 8 July 2016) held that an employee who died in a car crash after a company‑sponsored welcome/farewell party was still “under employer control.” Because the party served a clear business purpose and attendance was strongly encouraged by a superior—without relaxing an urgent work deadline—the Court treated the entire sequence (party ➜ driving trainees home ➜ returning to finish work) as work‑related. Accordingly, survivor benefits under the Workers’ Accident Compensation Insurance Act were granted.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: An Urgent Task, a Company Party, and a Fatal Detour

- Lower Court Rulings: Party and Driving Deemed Private Acts

- Legal Framework: Determining "Work-Relatedness"

- The Supreme Court's Analysis (July 8, 2016): A Holistic View

- Implications and Significance

- Conclusion

On July 8, 2016, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment concerning the scope of "work-relatedness" (gyōmu-jō no jiyū) for the purpose of eligibility for benefits under the Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act (WCAI Act, or Rōsai Hoken Hō - 労災保険法) (Case No. 2014 (Gyo-Hi) No. 494, "Survivor Compensation Benefit etc. Non-Payment Decision Revocation Case"). The case involved an employee who died in a traffic accident while driving company trainees home after attending a company-sponsored welcome/farewell party, having interrupted urgent work duties that he intended to resume immediately afterward. The Court overturned lower court decisions and found the death to be work-related, emphasizing a holistic assessment of the circumstances, including the employer's strong encouragement to attend the business-related event and the employee's actions being part of a continuous sequence under the employer's purview. This decision provides important insights into how Japanese law assesses whether activities peripheral to core work tasks, such as company social events and related travel, fall under the employer's sphere of control for workers' compensation purposes.

Factual Background: An Urgent Task, a Company Party, and a Fatal Detour

The circumstances leading to the fatal accident were key to the Court's decision:

- The Employee and His Role: B was an employee of Company A, working at its factory in Town A, Fukuoka Prefecture. He was on assignment (出向 - shukkō) from A's parent company, Company C, and his responsibilities included sales planning. Due to Company A's President (D, also a manager at Company C) often being away at Company C's headquarters in Nagoya, the day-to-day management of the factory, including acting presidential duties, was handled by the Production Manager, E.

- Company-Sponsored Trainee Events: Since opening the factory earlier that year (August 2010), Company A had a practice of hosting Chinese trainees from Company C's subsidiary in China for two-month training programs. Manager E had initiated the custom of holding welcome/farewell parties (kansōgeikai) for these trainees, explicitly aiming to foster camaraderie (shinboku o hakaru) between the trainees and the company's employees (numbering only seven, including B, at the time). The costs for these parties were consistently paid from Company A's welfare expenses budget.

- The Specific Welcome/Farewell Party: On December 6, 2010, with three trainees nearing their departure and two new trainees having just arrived, Manager E planned a welcome/farewell party for all five trainees (the "Trainees") for the following evening, December 7. E invited all employees; everyone except B initially accepted.

- B's Attendance: On December 7, Manager E specifically approached B again about attending the party. B declined, stating he needed to finish preparing an important sales strategy report ("the Report") for President D, which had a strict deadline of the next day, December 8. Despite B's refusal based on urgent work duties, Manager E strongly urged him to attend, saying, "Today is the last [day for the departing trainees], if you can show your face, please do." Notably, E did not offer to extend the deadline for the Report but instead told B that if the Report wasn't finished, E himself would help B complete it after the party ended.

- The Party and B's Brief Participation: The party began around 6:30 PM at Restaurant F in Town A, without B. All other employees and the five Trainees attended. Manager E took the lead, making the initial toast. Attendees then ate, drank, and socialized freely. Some employees and the Trainees consumed alcohol. Before the party, E had driven the Trainees from their company-provided apartment (Apartment G) to the restaurant in a company car, and he planned to drive them back afterward.

Meanwhile, B continued working on the Report at the factory. However, he eventually interrupted his work, put on his company work clothes, and drove a company car ("the Vehicle") to Restaurant F. He arrived around 8:00 PM, approximately 30 minutes before the party's scheduled end time. Upon arrival, B informed the company's general affairs manager that he intended to return to the factory to continue working after the party. The manager responded, "Just eat and leave quickly." B declined beer offered by a trainee and did not consume any alcohol. The party concluded shortly after 9:00 PM, and the bill was paid by Company A. - The Fatal Accident: After 9:00 PM, B left the restaurant driving the Vehicle. He had the five (intoxicated) Trainees as passengers. His stated intention was to drop the Trainees off at Apartment G and then return to the factory to resume work on the Report. While driving towards Apartment G, B's vehicle collided with an oncoming large truck. B suffered fatal head injuries and died around 9:50 PM ("the Accident"). Geographically, both the factory and Apartment G were located south of the restaurant, approximately 2 kilometers apart from each other, suggesting the detour to the apartment before returning to the factory was not significantly out of the way.

- WCAI Claim Denial: B's wife, X (the appellant), applied for survivor compensation benefits and funeral expenses under the WCAI Act. However, the Yukuhashi Labour Standards Inspection Office Director issued a decision denying the benefits ("the Decision"), concluding that B's death did not arise from work-related causes.

Lower Court Rulings: Party and Driving Deemed Private Acts

X challenged the denial in court. Both the first instance court and the Fukuoka High Court upheld the denial, finding the death was not work-related. The High Court essentially reasoned that:

- The welcome/farewell party, despite its company purpose and funding, was primarily a social gathering initiated by employee volunteers (jūgyōin yūshi) and thus a private meeting (shiteki na kaigō).

- B's mid-way participation was voluntary.

- The act of driving the trainees home was incidental to this private gathering and was undertaken voluntarily by B (nin'i ni okonatta unten kōi), not under the control or supervision of the employer (Company A).

- Therefore, the accident occurring during this driving did not happen while B was under the employer's control.

Legal Framework: Determining "Work-Relatedness"

For a death or injury to be compensable as a "work-related disaster" (gyōmu saigai) under the WCAI Act, it must be attributable to "work-related causes" (gyōmu-jō no jiyū). Established case law interprets this requirement as involving two key elements:

- Work Performance Capability / Being Under Employer Control (Gyōmu Suikōsei): The injury or death must have occurred while the worker was acting based on the employment contract and under the control and supervision of the employer (事業主の支配下にある状態 - jigyōshu no shihai ka ni aru jōtai). This doesn't necessarily mean actively performing core duties, but includes actions reasonably incidental to employment performed within the employer's sphere of influence.

- Work Causality (Gyōmu Kiinsei): The injury or death must have arisen out of a hazard inherent in the work or the conditions under which the work was performed. The harm must be a materialization of a risk associated with being under the employer's control in that context.

The lower courts denied benefits primarily based on a lack of the first element – they found B was not under Company A's control during the party or the subsequent drive.

The Supreme Court's Analysis (July 8, 2016): A Holistic View

The Supreme Court disagreed with the lower courts' segmented analysis and took a more holistic view of the entire sequence of events, concluding that B was indeed under the employer's control at the time of the fatal accident. The Court overturned the lower court decisions and revoked the original non-payment decision.

1. Reaffirming the Control Test: The Court began by restating the fundamental principle that work-relatedness requires the disaster to occur while the worker is under the employer's control based on the employment contract.

2. Analyzing the Specific Circumstances Holistically: The Court then meticulously examined the chain of events leading to the accident, highlighting several key factors:

- B's "Compelled" Attendance: The Court placed significant weight on the interaction between B and Manager E regarding party attendance. B's initial refusal due to an urgent, deadline-driven work task assigned by top management (President D) was overridden by Manager E's (acting president's) strong insistence ("Today is the last... please show your face"). Importantly, the work deadline was not relaxed; instead, E offered post-party assistance, implicitly linking the party attendance to the work requirement. The Court concluded B was placed in a situation where "he could not avoid participating" (sanka shinai wake ni wa ikanai jōkyō ni okare) and was "compelled to return to the factory... to resume the said work" (tōgai gyōmu o saikai suru tame... modoru koto o yoginaku sareta). From the company's perspective, this amounted to a "request based on job duties to undertake the series of actions" (shokumu-jō, jōki no ichiren no kōdō o toru koto o yōsei shite ita).

- Business Nature of the Event: The Court rejected the characterization of the party as merely private or social. It emphasized that the event was:

- Planned and initiated by the acting head of the factory (E).

- Attended by all other employees and the trainees.

- Funded entirely by the company (welfare expenses).

- Held for a clear business-related purpose: fostering good relations with trainees from an affiliated overseas subsidiary, thereby contributing to the training program's success and strengthening ties between Company A, its parent Company C, and the subsidiary.

- Therefore, the party was assessed as "part of an event planned by the company... closely related to the business activities of Company A." (kaisha ni oite kikaku sareta gyōji no ikkan... jigyō katsudō ni missetsu ni kanren shite okonawareta).

- Driving Trainees as Part of the "Requested Action": The Court viewed B's act of driving the trainees home not in isolation, but as part of the overall sequence.

- This task was originally planned to be performed by Manager E using a company car, indicating it was considered part of the event logistics managed by the company.

- B was using a company car.

- The route to the apartment before heading back to the factory was not a significant deviation.

- Given these points, B taking over this task from E was deemed "within the scope of the series of actions requested by the company." (kaisha kara yōsei sarete ita ichiren no kōdō no han'i nai no mono).

3. Overall Conclusion on Employer Control:

Synthesizing these elements, the Court concluded: "B was placed in a situation by Company A where he could not avoid participating in the welcome/farewell party which was closely related to its business activities, leading him to interrupt his work at the factory to participate midway, and upon returning to the factory in the Vehicle after the party to resume said work, he was concurrently taking the Trainees to the Apartment in place of Manager E when he met with the Accident."

Therefore, "even considering" factors like the party being off-site, alcohol being served (though not consumed by B), and the lack of an explicit order for B to drive the trainees, "B should be said to have still been under the control of Company A at the time of the Accident." (B wa, honken jiko no sai, nao honken kaisha no shihai ka ni atta to iu beki de aru).

4. Causation: The Court also briefly affirmed the existence of proximate cause between B's driving (undertaken within this sphere of control) and his death.

5. Final Determination: Consequently, the Court ruled that B's death was a disaster arising from work-related causes under the relevant statutes (WCAI Act Art. 1, Art. 12-8(2); LSA Art. 79, 80). The LSIO Director's decision denying benefits was therefore illegal.

Implications and Significance

This 2016 Supreme Court ruling provides important guidance on assessing work-relatedness, particularly for activities occurring outside standard work hours or premises, such as company-sponsored social events:

- Holistic Assessment is Key: The decision strongly favors a holistic assessment of the entire sequence of events rather than analyzing each component (e.g., attending the party, driving afterward) in isolation. The employee's overall situation and the employer's role throughout must be considered.

- Employer Encouragement/Pressure Matters: Even without a direct order, strong encouragement or pressure from a superior to participate in a company event, especially when linked to work duties (like needing help afterward), can place the employee's participation and related travel under the employer's control. The lack of freedom to refuse becomes a significant factor.

- Business Purpose of Social Events: Company-sponsored social events are more likely to be considered work-related if they have a clear business purpose (e.g., team building, client relations, inter-company relations, training support) beyond mere recreation, are initiated and funded by management, and involve broad or expected participation.

- Incidental Tasks Can Be Covered: Tasks undertaken incidentally to a work-related event, especially if they substitute for a manager's planned action and occur on a reasonable route related to work (like returning to the office/factory), can also fall within the employer's sphere of control.

- Substance Over Form: The ruling reaffirms that the substance of the situation – the degree of employer involvement and control, the connection to business activities – is more important than formal characteristics like the location (off-site) or the presence of alcohol.

This decision may encourage a broader interpretation of work-relatedness in contexts involving company events, potentially increasing employer liability and the scope of workers' compensation coverage, but always requiring a careful examination of the specific factual matrix.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's July 8, 2016, judgment determined that an employee who died in a traffic accident while driving company trainees home after attending a company-sponsored, business-related welcome/farewell party – an event he felt compelled to attend despite urgent work duties he intended to resume – was considered to be under the employer's control at the time of the accident. The Court's holistic evaluation emphasized the manager's strong encouragement, the event's connection to business goals, and the fact that the driving was part of a continuous, work-related sequence. This ruling clarifies that the assessment of "work-relatedness" under Japan's WCAI Act extends beyond core job tasks to encompass activities significantly influenced or required by the employer, even if seemingly social or occurring outside normal work parameters.