Work Halted by Client: Can Contractor Claim Full Pay? A Japanese Supreme Court View

Date of Judgment: February 22, 1977

Case Name: Claim for Contract Price

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Introduction

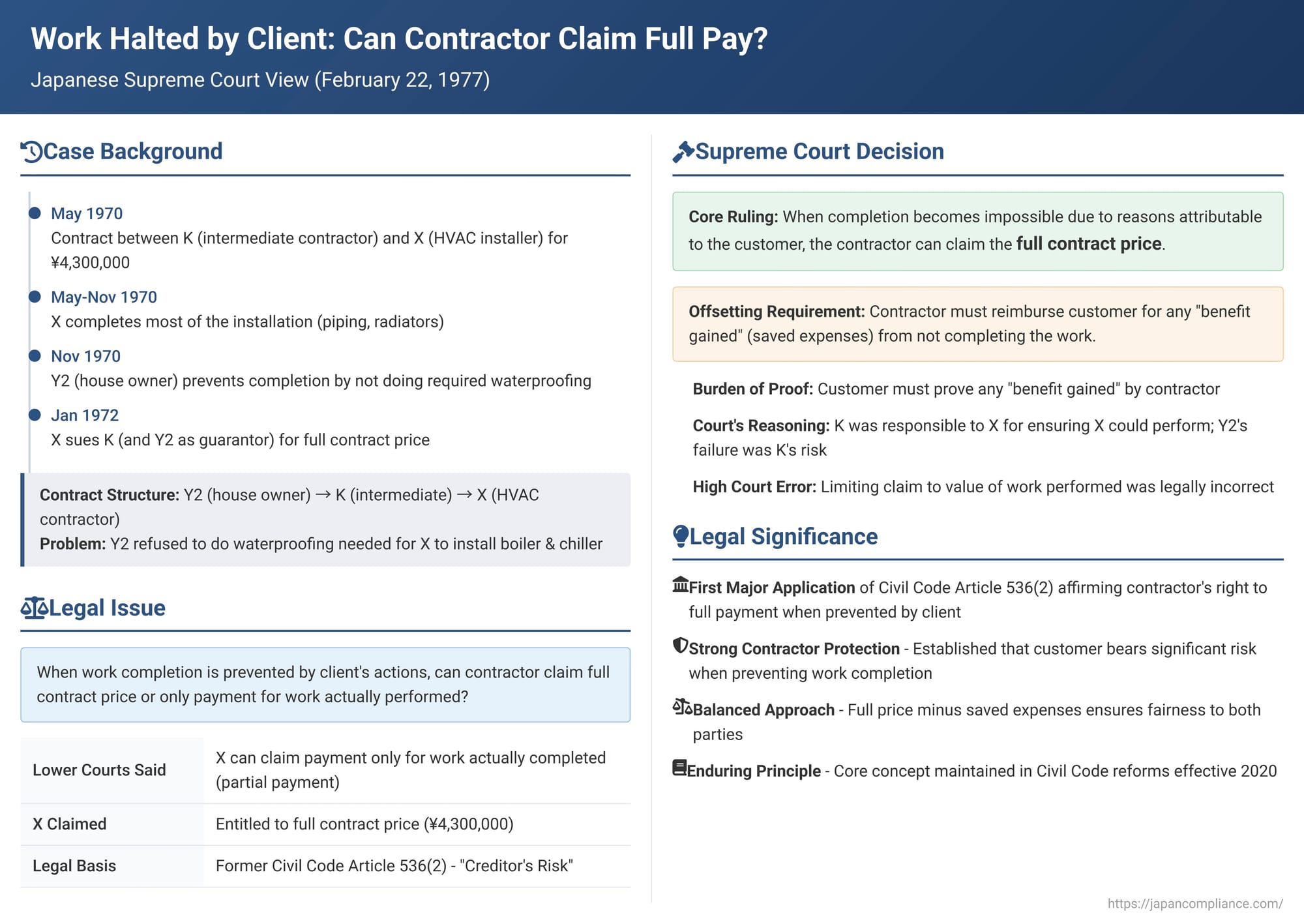

In construction and service contracts, it's not uncommon for a project to be derailed by actions (or inactions) of the client or customer. When a contractor is prevented from completing agreed-upon work due to reasons attributable to the customer, a critical question arises: what payment is the contractor entitled to? Can they claim the full contract price, or only payment for the work actually performed before the stoppage? A Japanese Supreme Court decision from February 22, 1977, provided significant clarification on this issue under the then-existing Civil Code.

A Chain of Contracts and a Waterproofing Problem: The Factual Background

The case involved a multi-layered contractual arrangement for an HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) installation:

- The Parties:

- Y2: The owner of a house that was under construction.

- K: An intermediate contractor. K's business model for larger projects was to secure the main contract and then sub-contract the actual labor, earning a fee in the process.

- X: A specialized HVAC installation company.

- The Contracts:

- In early May 1970, Y2 (the house owner) entered into a contract with K for the HVAC installation in her house.

- With Y2's consent, K then sub-contracted this HVAC work to X. On May 12, 1970, X (as the performing contractor) and K (as X's direct customer) signed a contract (the "Subject Contract") for X to carry out the HVAC installation for a price of ¥4,300,000, payable in cash upon completion.

- Y2 (the house owner) acted as a joint guarantor for K's payment obligation to X.

- Work Stoppage: X proceeded with the work and, by mid-November 1970, had completed most of it, including piping and radiator installation. Only the final installation of the boiler and chiller units remained.

However, Y2 refused to allow X to install these units. Y2 stated that waterproofing work first needed to be done in the basement area where the boiler and chiller were to be located. Despite repeated requests from both X and K, Y2 failed to carry out this necessary waterproofing work, thereby physically preventing X from completing the final phase of the HVAC installation. As a result, X was unable to finish the contracted work. - Litigation and Lower Court Rulings:

- On January 19, 1972, X sued K for the full contract price of ¥4,300,000 (plus interest) and sued Y2 as the guarantor.

- The first instance court awarded X a lesser amount (approximately ¥2,730,000, likely representing the value of the work completed) and dismissed the remainder of X's claim.

- Y2 appealed this decision. The High Court dismissed Y2's appeal. It reasoned that the impossibility of completing the work was due to reasons attributable to Y2 (the ultimate beneficiary and party controlling site access). It held that K (as X's customer) was responsible to X for this. However, the High Court, applying former Article 536, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code (which dealt with the "creditor's risk" – where the party due to receive performance prevents it), concluded that K owed X payment only for the portion of work actually completed. Y2, as guarantor, was liable for this reduced amount.

Y2 further appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Analysis

The Supreme Court, in its judgment on February 22, 1977, dismissed Y2's appeal, meaning Y2 remained liable. However, the Supreme Court significantly diverged from the High Court's reasoning regarding the amount K (and therefore Y2) legally owed X, even though this didn't change the outcome for Y2 since X hadn't appealed for a higher amount.

Impossibility and Attributability

The Supreme Court first affirmed the lower courts' findings that:

- Completion of the remaining HVAC work by X had become impossible, in a practical, socio-economic sense, by the time X initiated the lawsuit.

- This impossibility was due to reasons attributable to K (X's direct customer). The Court reasoned that while Y2 directly prevented the work, the necessary preparatory work (like waterproofing) was fundamentally within K's sphere of responsibility in the context of the K-X contract (as K was responsible for ensuring X could perform). Y2's failure to act was thus a risk K bore in its relationship with X.

Contractor's Right to Full Remuneration (under Former Civil Code Article 536(2))

This was the core of the Supreme Court's legal clarification:

- When the completion of work under a contract becomes impossible before the work is finished, and this impossibility is due to reasons attributable to the customer (the party who ordered the work – in this case, K, for whom Y2's actions were decisive):

- The contractor (X) is relieved of their obligation to perform the remaining, uncompleted portion of the work.

- Crucially, under the provisions of former Civil Code Article 536, Paragraph 2, the contractor (X) is entitled to claim the full, original contract price from the customer (K).

- The contractor (X) then has an obligation to reimburse the customer (K) for any "benefit gained" (e.g., saved expenses) that resulted from being relieved of the duty to complete the work. This could include, for example, the cost of materials not purchased or labor not expended for the unfinished portion.

Onus of Proving "Benefit Gained"

The Supreme Court implicitly indicated that the burden of asserting and proving any such "benefit gained" or "saved expenses" by the contractor rests with the customer. In this case, neither K nor Y2 had made any claims or presented evidence that X had saved any specific costs by not installing the boiler and chiller.

High Court's Legal Error (but no change in outcome for appellant Y2)

The Supreme Court stated that the High Court had erred in its interpretation of former Civil Code Article 536(2) by limiting X's claim to only the value of the work already performed. Legally, X was entitled to claim the full ¥4,300,000 from K (and Y2 as guarantor), less any proven saved expenses.

However, X had not appealed the first instance court's decision (which awarded less than the full price and was upheld by the High Court). Since X was not seeking more money at the Supreme Court stage, the High Court's legal error regarding the amount did not negatively affect Y2 in a way that would require overturning Y2's loss (Y2 was still liable for at least the sum awarded by the lower courts, and under the Supreme Court's correct interpretation, would have been liable for more had X pursued it).

Unpacking the "Customer's Fault" Rule: Significance and Implications

This 1977 Supreme Court decision was significant for being the first clear instance where the Court applied former Civil Code Article 536(2) to affirm a contractor's right to claim the full contract price (not just payment for work done) when project completion was made impossible by the customer.

Former Civil Code Article 536(2) – Creditor's Risk

This provision of the (now revised) Civil Code addressed situations where one party's performance of an obligation in a bilateral contract becomes impossible. If the impossibility was due to an act of the "creditor" (in the context of a specific obligation, the party entitled to receive that performance – for the work itself, this is the customer) or due to a cause for which the creditor was responsible, the "debtor" (the party obliged to perform – the contractor) did not lose their right to claim the counter-performance (i.e., payment).

Scope of "Full Remuneration"

The Supreme Court's interpretation confirmed that this right to counter-performance meant the entire agreed contract sum. Legal commentary suggests this was because Article 536(2) was viewed as providing the performing party (contractor) with a right to their expected payment, akin to a standardized form of damages for the customer's prevention of performance.

The "Benefit Gained" Offset

The rule ensures fairness by requiring the contractor to pass back any savings accrued from not having to complete the work. If, for instance, a contractor had budgeted ¥100,000 for materials for the final phase and didn't have to buy them due to the customer's stoppage, that ¥100,000 would be a "benefit gained" to be deducted from the full contract price claimed. However, the customer must raise this issue and provide evidence of such savings.

Relevance under the Current Civil Code (Post-2017/2020 Reforms)

Japan's Civil Code underwent significant revisions, with many changes taking effect in 2020. Former Article 536 was among the articles restructured. However, the underlying principle concerning the "creditor's risk" when the creditor (customer) makes performance impossible is considered to have been substantially carried over into the newly formulated Article 536, Paragraph 2. The new provision is framed such that the customer cannot refuse their own obligation (payment) if the contractor's performance became impossible due to a cause attributable to the customer.

Therefore, legal commentators generally expect that, even under the current Civil Code, a contractor prevented from completing work due to the customer's fault would still be able to claim their remuneration, likely the full price less saved expenses, based on the application or underlying spirit of the revised Article 536(2).

It's also important to distinguish this situation (impossibility due to customer's fault) from scenarios covered by other Civil Code provisions, such as the (also revised) Article 634, which deals with situations like "deemed completion" of divisible work or termination before completion due to reasons not attributable to the customer. The 1977 Supreme Court case specifically addresses the consequences of the customer being the source of the impossibility.

Conclusion

The 1977 Supreme Court decision provides robust protection for contractors in Japan when a customer's actions or failures render project completion impossible. It established that the contractor is generally entitled to claim the full agreed contract price, not just payment for work partially completed. The customer then has the opportunity to reduce this claim by proving any specific costs the contractor saved by not having to finish the job. This principle, emphasizing the customer's responsibility for the consequences of their own actions preventing performance, appears to be largely maintained in its substance under Japan's current Civil Code.