Women on Boards in Japan: Corporate Governance as a Catalyst for Gender Diversity

TL;DR

Japan’s Corporate Governance Code, new disclosure rules and investor pressure are accelerating female board appointments. Prime-market issuers must have at least one woman director by 2025 and target 30 % by 2030. For US firms in Japan, proactive succession planning and transparent nomination processes are critical to meet rising ESG expectations.

Table of Contents

- The Shifting Landscape: From Laggard to Gradual Progress

- Key Drivers of Change in Japan

- The Corporate Governance Code (CGC): A "Comply or Explain" Nudge

- The Women’s Advancement Act

- FSA and Tokyo Stock Exchange Initiatives

- Investor Pressure and ESG Focus

- The Rationale: Why Prioritize Women on Boards in Japan?

- Approaches to Promoting Board Diversity: Quotas vs. "Comply or Explain"

- Ongoing Challenges and the Path Ahead

The global push for greater gender diversity in corporate leadership has firmly reached Japan, a nation historically known for its male-dominated boardrooms. While progress has been gradual, a confluence of evolving corporate governance standards, legislative nudges, and shifting investor expectations is creating new momentum. For U.S. companies operating in or engaging with Japan, understanding this dynamic is crucial for aligning with best practices, meeting stakeholder expectations, and recognizing the changing face of Japanese corporate leadership.

This article explores how corporate governance mechanisms are playing a role in promoting the appointment of women to directorships and executive positions in Japanese companies, the key drivers behind this shift, and the ongoing challenges.

The Shifting Landscape: From Laggard to Gradual Progress

Japan has traditionally lagged behind other major economies in terms of female representation on corporate boards. However, recent years have seen a notable increase in awareness and a series of initiatives aimed at addressing this imbalance.

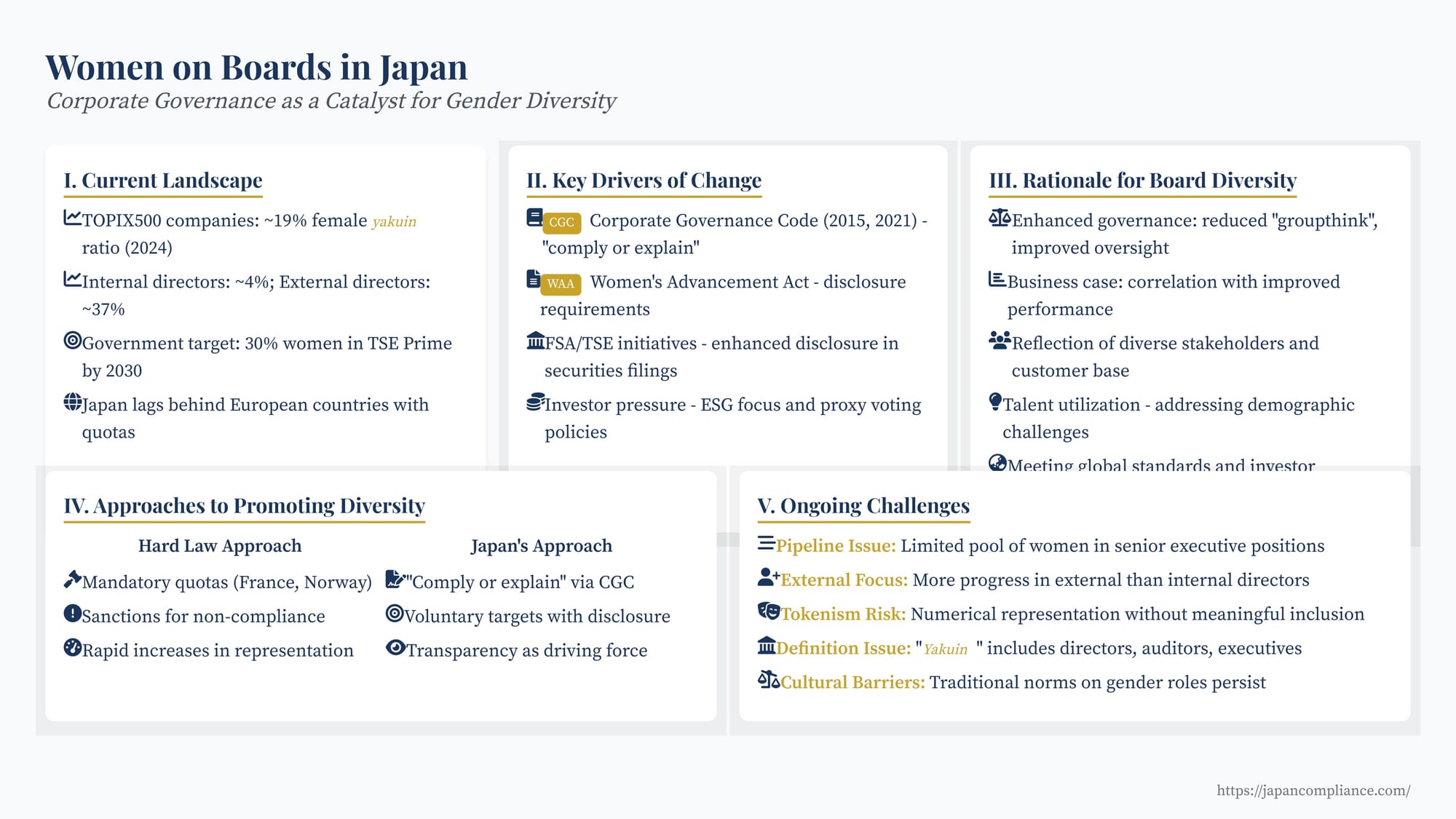

- The Global Context and Japan's Position: Internationally, many countries, particularly in Europe, have adopted various measures, including legislated quotas (like in France and Norway) or "comply or explain" mechanisms within corporate governance codes (common in the UK), to boost the number of women on boards. The U.S. has seen progress driven by a mix of investor pressure, state-level legislative efforts (like California's past mandates), and exchange-led initiatives such as Nasdaq's board diversity rules. In comparison, Japan's figures for women in boardrooms (directors, auditors, and executive officers) remain relatively low, though they are on an upward trend. For example, recent data for 2024 indicates that the average female役員 (yakuin - officer, a broad term including directors, auditors, and executive officers) ratio in TOPIX500 companies was around 19%, with a lower percentage for internal directors compared to external directors.

- Government Targets and Policy Signals: The Japanese government has set ambitious goals. The "Women's Version of the Basic Policy" (女性版骨太の方針 - joseiban honebuto no hōshin) has outlined targets, including aiming for a 30% ratio of women in executive positions in companies listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) Prime Market by 2030. An interim goal was also set to have at least one female executive in such companies by 2025. These targets, while not hard quotas with direct penalties for non-compliance, send a strong signal to the market.

Key Drivers of Change in Japan

Several interconnected factors are contributing to the increased focus on gender diversity in Japanese boardrooms:

1. The Corporate Governance Code (CGC): A "Comply or Explain" Nudge

Japan's Corporate Governance Code, first introduced by the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) in 2015 and revised several times (e.g., 2018, 2021), has been a significant catalyst. The Code operates on a "comply or explain" basis, meaning listed companies must either adhere to its principles or explain why they do not.

- Evolution of Diversity Provisions: Early versions of the Code encouraged companies to consider diversity, including gender, in board composition. The 2021 revision of the CGC (Supplementary Principle 2.4.1) went further, asking companies to disclose their policy and voluntary, measurable targets for ensuring diversity in the promotion of core human resources, including the appointment of women, foreign nationals, and mid-career hires to managerial positions, as well as the status of these initiatives.

- Focus on Board Effectiveness: The rationale often cited is that diverse boards, bringing a wider range of perspectives, experiences, and skills, lead to better decision-making, more effective risk management, and ultimately, enhanced corporate value. The Code encourages companies to view board diversity not just as a social issue but as integral to effective governance.

- Role of Nomination Committees: The Code also emphasizes the importance of transparent and objective director nomination processes, often recommending the establishment of independent nomination committees. These committees are expected to consider diversity when identifying and recommending board candidates.

2. The Act on Promotion of Women's Participation and Advancement in the Workplace (Women's Advancement Act)

While not directly targeting board composition in its initial mandates, the Women's Advancement Act (Josei Katsuyaku Suishin Hō) has played an indirect yet crucial role by increasing transparency and focusing corporate attention on female career progression more broadly.

- Disclosure Requirements: As outlined in previous discussions, this Act requires companies (now generally those with 101 or more employees) to analyze their female workforce, set targets for women's advancement (including in managerial roles), formulate action plans, and publicly disclose this information. The mandatory disclosure of the ratio of female managers and, for larger companies, the gender pay gap, brings a new level of scrutiny.

- Creating a Pipeline: By encouraging companies to focus on the pipeline of female talent from recruitment through to managerial levels, the Act indirectly supports the development of a larger pool of potential female board candidates for the future. A common challenge cited for low female board representation is the lack of women in senior executive roles who would traditionally be considered for board positions.

3. Financial Services Agency (FSA) and Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) Initiatives

Regulatory bodies have also become more proactive.

- Enhanced Disclosure in Securities Filings: Following recommendations from working groups, the FSA has moved to require more detailed disclosure of human capital and diversity information in annual securities reports (yūka shōken hōkokusho). This includes metrics like the ratio of female managers, male childcare leave uptake, and the gender pay gap for listed companies (from March 2023 fiscal year-end reports). This makes diversity a more central part of corporate reporting to investors.

- TSE Listing Rules and Market Expectations: The Tokyo Stock Exchange itself has incorporated government targets into its own guidelines for Prime Market listed companies. For instance, it encourages these companies to strive for at least one female executive by 2025 and aim for a 30% female executive ratio by 2030, and recommends they formulate action plans to achieve these goals. This clearly signals market expectations.

4. Investor Pressure and ESG Focus

There is a growing global and domestic trend among institutional investors to consider Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors in their investment decisions. Board diversity, particularly gender diversity, is a key "S" (Social) and "G" (Governance) metric.

- Engagement and Voting Policies: Major institutional investors, both Japanese and international, are increasingly engaging with companies on their diversity efforts. Some have adopted voting policies that may lead them to vote against the re-election of directors (particularly chairs of nomination committees or top executives) at companies that lag significantly in board gender diversity without clear plans for improvement.

- The "Business Case" for Diversity: Investors are not just pushing for diversity for social reasons. Many are convinced by the "business case" – the argument that diverse boards contribute to better financial performance, innovation, and long-term corporate value. This perspective aligns with the idea that diverse viewpoints lead to more robust discussions, better risk oversight, and a deeper understanding of diverse customer bases and workforces.

The Rationale: Why Prioritize Women on Boards in Japan?

The push for more women on Japanese boards is underpinned by several interconnected rationales:

- Enhanced Corporate Governance: Diverse boards are believed to be more effective. Different perspectives can challenge "groupthink," lead to more thorough scrutiny of management proposals, and improve the quality of strategic decision-making. The presence of women can bring different experiences and approaches to problem-solving and risk assessment.

- Improved Financial Performance (The "Business Case"): While the direct causal link between board gender diversity and financial performance is a subject of ongoing academic research with mixed results globally, many studies suggest a positive correlation. Companies with more diverse boards are sometimes seen to outperform their less diverse peers. The argument often centers on better decision-making, enhanced innovation, and a stronger connection with a diverse customer and talent market.

- Reflecting Society and Stakeholders: Corporate boards make decisions that impact a wide range of stakeholders, including employees, customers, and the broader community. A board that is more reflective of society's diversity is often seen as better equipped to understand and respond to the needs and expectations of these varied groups.

- Talent Utilization and Role Models: Japan faces demographic challenges, including a shrinking workforce. Fully utilizing the talent pool, including highly educated and experienced women, is an economic imperative. Having women in visible leadership positions on boards can also serve as powerful role models, encouraging younger women to aspire to senior roles and helping to break down traditional career progression barriers.

- Meeting Global Standards and Investor Expectations: As Japanese companies operate in a globalized economy and compete for international capital, aligning with global best practices in corporate governance, including board diversity, becomes increasingly important. International investors, in particular, often have clear expectations regarding ESG performance.

Approaches to Promoting Board Diversity: Quotas vs. "Comply or Explain"

Globally, approaches to increasing female board representation vary.

- Gender Quotas: Some European countries (e.g., France, Norway, Belgium, Italy) have implemented legally mandated gender quotas for the boards of listed companies, often with sanctions for non-compliance. This "hard law" approach has generally led to rapid increases in female representation.

- "Comply or Explain" and Voluntary Targets: Other jurisdictions, including the UK and Japan (via its CGC), have relied more on "soft law" mechanisms like "comply or explain" and the encouragement of voluntary target-setting by companies, coupled with disclosure requirements. The US has a mixed approach with some state-level mandates, exchange rules, and strong investor advocacy.

In Japan, the debate continues regarding the most effective path. While the government has set national aspirational targets (like 30% by 2030 for Prime Market companies), there has been a general reluctance to impose hard, legally binding quotas across the board. The current approach favors encouraging voluntary efforts within the "comply or explain" framework of the Corporate Governance Code and leveraging transparency through disclosure obligations under the Women's Advancement Act and financial reporting rules. The effectiveness of this approach often depends on the strength of market and investor pressure, as well as genuine corporate commitment.

Ongoing Challenges and the Path Ahead

Despite the progress and the various drivers, significant challenges remain in achieving substantial gender diversity on Japanese boards:

- The "Pipeline" Issue: A persistent challenge is the relatively small pool of women in senior executive positions within Japanese companies, who would traditionally be the primary candidates for internal board appointments. While efforts are underway to improve the pipeline through women's advancement initiatives, this takes time.

- Focus on External Directors: Much of the initial increase in female directors in Japan has been through the appointment of external (outside) directors rather than promoting women from within executive ranks to executive director positions. While external directors bring valuable independence and expertise, developing internal female leadership for board roles is also crucial for sustainable change. Recent statistics (e.g., for 2024) show that while the overall female officer ratio for TOPIX500 companies is around 19%, the ratio for female internal directors is much lower (around 4%), with female external directors being more common (around 37%).

- Cultural and Traditional Norms: Deep-seated cultural norms regarding gender roles and career paths can still subtly influence nomination processes and the willingness of companies to break from traditional board compositions.

- Definition of "Executive": The Japanese targets often refer to 女性役員 (josei yakuin), which can include directors, statutory auditors (kansayaku), and executive officers (shikkō yakuin or even shikkō yakuin-level positions). While this broad definition aims to be inclusive, focusing specifically on board-level (director) representation remains important for direct governance impact.

- Beyond Tokenism: The pressure to meet targets can sometimes lead to "token" appointments if not accompanied by a genuine commitment to leveraging the diverse perspectives women bring. Ensuring that female directors are fully integrated and can meaningfully contribute is as important as their numerical representation.

The drive for more women on Japanese boards is clearly gaining traction, propelled by a combination of governance reforms, legislative action, and evolving market expectations. For U.S. businesses, understanding this trend is vital. It reflects a broader shift in Japanese corporate culture towards greater inclusivity and alignment with global governance standards. While the pace of change may sometimes seem slow compared to other regions, the direction is clear. Companies that proactively embrace and champion gender diversity in their leadership structures are likely to be better positioned for long-term success and resilience in the Japanese and global markets.