Withholding Tax Errors: Can They Be Fixed on Your Final Japanese Tax Return?

Date of Judgment: February 18, 1992

Case Name: Claim for Revocation of Income Tax Reassessment Disposition (平成2年(行ツ)第155号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

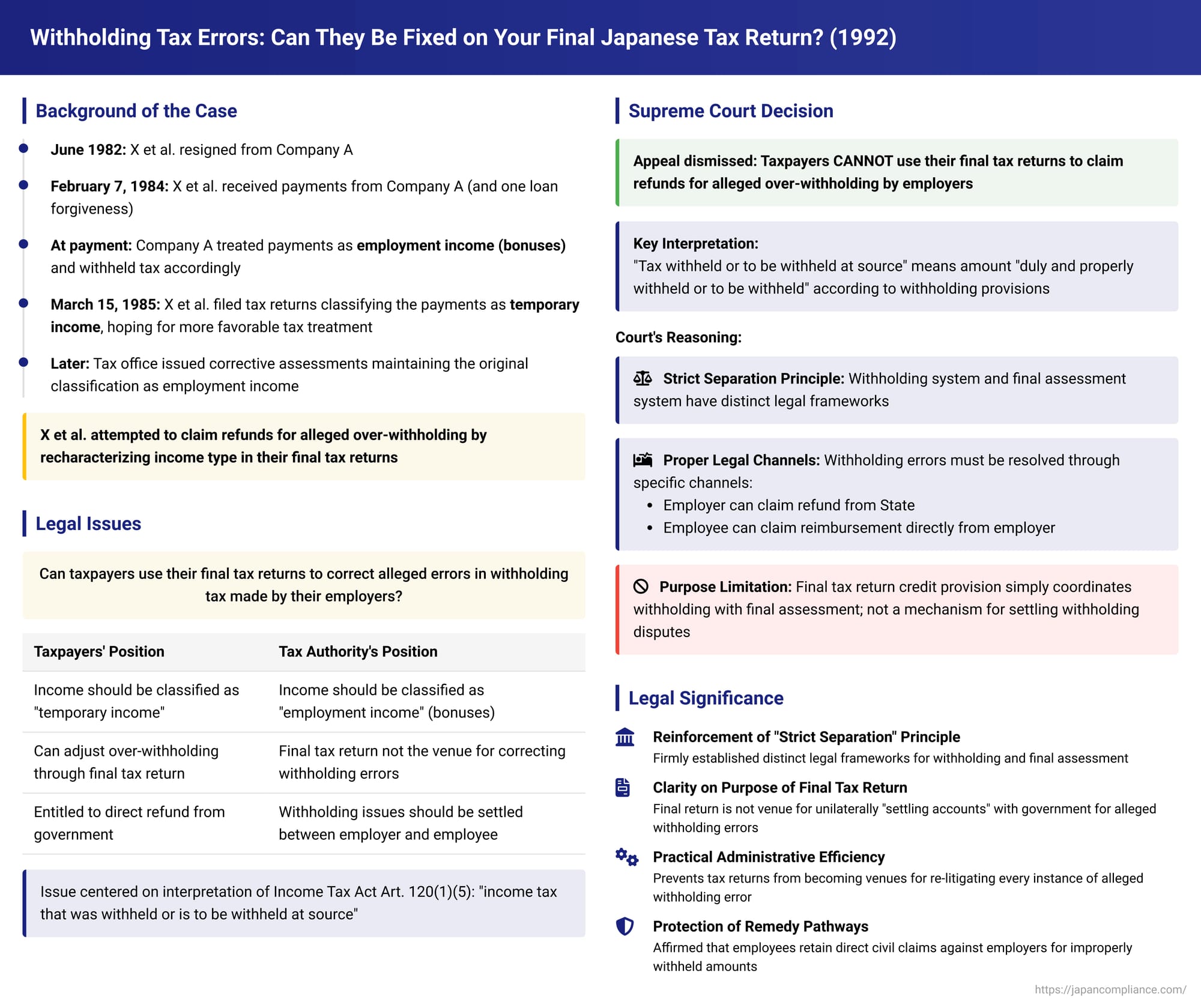

In a significant judgment on February 18, 1992, the Supreme Court of Japan provided a crucial clarification on the distinct nature of Japan's income tax withholding system and the final self-assessment tax return process. The case addressed whether taxpayers, in their final income tax returns, could unilaterally adjust for alleged errors in income tax withholding made by their employers, particularly when also recharacterizing the nature of the income received. The Court firmly established that the final tax return is not the proper venue for settling such withholding discrepancies.

The Disputed Payments: Bonus or Temporary Income?

The appellants, X et al., were former officers and employees of Company A. They had resigned from Company A in June 1982. Subsequently, on February 7, 1984, X et al. received certain monetary payments from Company A. Additionally, one individual among X et al. also received forgiveness for a loan previously taken from Company A. These payments and the debt forgiveness are collectively referred to as "the subject payments."

Company A, when making these payments, treated them as employment income (specifically, bonuses) for tax purposes. Accordingly, Company A withheld income tax at source from the subject payments based on the rates applicable to employment income and remitted these withheld amounts to the government.

However, when X et al. filed their individual income tax returns for the 1984 tax year (on March 15, 1985), they took a different stance. They declared the subject payments not as employment income, but as "temporary income" (一時所得 - ichiji shotoku), a distinct category of income under Japanese tax law that is often subject to different calculation rules and potentially a more favorable tax treatment. In their returns, X et al. listed the amounts that Company A had withheld (as if for employment income) as if this withholding had been done on "temporary income." Based on their recharacterization of the income and their recalculation of the tax due, they claimed a partial refund of the tax that Company A had withheld and paid to the government.

The respective district tax office heads, Y et al. (the respondents), reviewed these returns and issued corrective assessments (更正処分 - kōsei shobun). The tax offices maintained that the subject payments were, in fact, employment income, not temporary income. Consequently, they reduced the amount of the tax refunds that X et al. had claimed. X et al. challenged these corrective assessments, ultimately bringing their case before the Supreme Court after unsuccessful appeals in the lower courts.

The Nagoya District Court (first instance) had ruled against X et al., stating that if income tax is improperly or excessively withheld at source by a payer, only the payer (the employer) can seek a refund of the erroneous amount from the State. The income recipient (the employee), while potentially able to claim the over-deducted amount directly from the payer, cannot directly seek a refund from the State for such withholding errors through their final tax return. The Nagoya High Court affirmed this decision, emphasizing that the legal relationship between the State and the withholding agent (employer) is entirely separate from the legal relationship between the State and the self-assessing taxpayer (employee). It concluded that current law did not permit the recipient to adjust for overages or shortages in source withholding during the final tax return process.

The Legal Question: Settling Withholding Discrepancies in the Final Return?

The central legal question before the Supreme Court was whether an income recipient (taxpayer) can use their final self-assessed income tax return to correct alleged errors—specifically, over-withholding—made by the payer (employer) in the income tax withholding process. This was particularly pertinent as the taxpayers were also attempting to recharacterize the nature of the income (from employment to temporary) differently from how the employer had treated it for withholding purposes.

Essentially, the Court had to determine the meaning of "income tax that was withheld or is to be withheld at source" (源泉徴収をされた又はされるべき所得税の額 - gensen chōshū o sareta mata wa sareru beki shotokuzei no gaku) as stated in Article 120, paragraph 1, item 5 of the Income Tax Act. This is the amount that a taxpayer can credit against their total calculated income tax liability in their final return. Does this refer to the amount actually withheld by the payer, regardless of its correctness, or does it refer only to the amount that should have been legally and correctly withheld according to the specific withholding provisions?

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Withholding and Final Assessment are Separate Tracks

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by X et al., affirming the lower courts' decisions. The Court held that taxpayers cannot use their final income tax returns to claim refunds from the State for amounts they allege were over-withheld at source by their employers.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Meaning of "Tax Withheld or to be Withheld at Source" (Income Tax Act Art. 120(1)(5)): The Supreme Court interpreted this crucial phrase to mean the amount of income tax that was "duly and properly withheld or is to be withheld" (正当に徴収をされた又はされるべき - seitō ni chōshū o sareta mata wa sareru beki) in accordance with the specific income tax withholding provisions found in Part IV of the Income Tax Act. It clarified that this does not mean that if an employer (payer) makes an error and withholds an incorrect amount of tax, the employee (recipient) can then use their final tax return process to either deduct that erroneously withheld larger sum from their final tax liability or claim a refund from the State for the portion they believe was erroneously withheld.

- Strict Separation of Legal Relationships: The Court strongly reaffirmed the principle of "strict separation" (genkaku bunri) between the legal mechanics of the withholding tax system and the final self-assessment system for income tax. It cited its own prior judgment (Supreme Court, December 24, 1970, Minshu Vol. 24, No. 13, p. 2243 – the "Maruishi Chemical Pharmaceutical Co. case," which is case t114) to underscore these distinct relationships:

- Employer's Duty: The obligation to withhold and remit income tax at source is legally borne by the payer of the income (the employer). This liability of the employer is separate and distinct from the recipient's (employee's) liability for their overall income tax, which is finalized through their own self-assessment tax return.

- Addressing Shortfalls in Withholding: If there is a shortfall in the amount of tax withheld and remitted, the tax authorities pursue the payer (withholding agent) for the deficient amount (as per Article 221 of the Income Tax Act). The payer, in turn, has a statutory right to seek reimbursement of this amount from the recipient (employee) (as per Article 222 of the Income Tax Act).

- Addressing Errors (Over-withholding): If an error occurs in the withholding and remittance process, such as over-collection by the payer:

- The payer can claim a refund of the erroneously paid amount from the State (under Article 56 of the General Act of National Taxes).

- The recipient (employee), from whom too much tax was withheld, can directly demand repayment of the over-deducted amount from the payer. The Court characterized this as a claim for partial non-performance of the original payment obligation (e.g., the salary owed), and the employee does not need to go through any special tax procedure to make this claim against the payer.

- No Direct State-Recipient Relationship in Withholding Act: The Supreme Court emphasized that there is no direct legal relationship between the State and the income recipient concerning the act of withholding or the specific amount withheld by the payer. The State's direct legal relationship regarding the administration of withholding tax is solely with the payer/withholding agent.

- Purpose of the Withholding Tax Credit in the Final Return: Based on this principle of separate legal relationships, the Court concluded that the provision allowing a credit for withheld tax in the final tax return (Article 120, paragraph 1, item 5) is intended merely to coordinate the withholding system with the self-assessment system. It allows the taxpayer to credit against their final assessed tax liability the amount of income tax that should have been duly and properly withheld according to the applicable withholding provisions. It is not intended to be a mechanism for settling or adjusting any overpayments or underpayments that may have occurred during the actual withholding process undertaken by the payer. Such discrepancies, the Court implied, must be resolved through the distinct legal channels outlined above (i.e., between the payer and the State, or between the payer and the recipient).

- No Prejudice to Recipient's Rights: The Court also noted that this interpretation does not unduly prejudice the rights of the income recipient. If an employer erroneously withholds too much tax from an employee's salary, the employee has a direct civil claim against the employer for the improperly withheld portion. They can demand this amount back from the employer immediately. Thus, not allowing them to use their final tax return to claim this specific over-withheld amount directly from the State does not leave them without a remedy.

Consequently, since X et al. were attempting to use their final tax returns to claim a refund from the State for amounts they alleged were over-withheld by Company A (and further complicated by their attempt to recharacterize the income type), the Supreme Court found this approach to be impermissible under the structure of the Income Tax Act. Their appeal was therefore dismissed.

The Supreme Court also briefly touched upon the "total amount principle" (sōgakushugi) in tax litigation, stating that the subject of judicial review in a lawsuit to cancel a tax assessment is the appropriateness of the total tax amount determined by that assessment. Even if the tax office makes an error in, for example, classifying the source or type of income, the assessment itself will generally be considered lawful if the final tax amount determined by that assessment does not exceed the amount that is objectively due under the tax laws.

Analysis and Implications

This 1992 Supreme Court decision is a cornerstone ruling that reinforces several key aspects of Japanese income tax procedure:

- Reinforcement of the "Strict Separation" Principle: The judgment is a strong affirmation of the distinct legal frameworks governing the withholding of income tax at source (primarily an employer-State relationship) and the final determination of an individual's annual income tax liability through self-assessment (an employee-State relationship). One process is not generally used to correct errors in the other.

- Clarity on the Scope of the Final Tax Return: The decision makes it clear that the final income tax return is for declaring one's total income for the year and calculating the final tax liability thereon, with a credit for properly withheld taxes. It is not a mechanism for taxpayers to unilaterally "settle accounts" with the government for alleged errors made by third-party withholding agents.

- Practical Considerations for Tax Administration: As legal commentary has pointed out, allowing final tax returns to become a venue for re-litigating every instance of alleged withholding error by numerous employers could create significant administrative burdens for both taxpayers and tax authorities. The Supreme Court's approach maintains a clearer, more manageable administrative process.

- Interaction with Later Rulings (e.g., the Heisei 22 Pension Withholding Case): It's interesting to consider this ruling in light of subsequent Supreme Court decisions. For instance, a 2010 (Heisei 22) judgment (case t34.pdf) dealt with a situation where pension payments were, under the specific facts, effectively non-taxable as income to the recipient (because they represented a return of capital already subject to inheritance tax). However, the Supreme Court held that the payer of the pension was still obligated to withhold income tax according to the general withholding rules applicable to pensions at the time, as those rules did not hinge on the ultimate income taxability to the recipient. In that H22 case, the recipient was allowed to claim a refund of this "duly" (though, in an economic sense, perhaps unnecessarily) withheld tax through their final tax return. Legal commentators suggest that the H22 decision does not necessarily contradict the principles of the H4 (1992) ruling. Instead, it may refine the understanding of "tax duly withheld or to be withheld" to mean tax withheld in accordance with the formal requirements of the specific withholding provisions applicable to that type of payment, even if the underlying income might ultimately be treated differently (e.g., as non-taxable) in the recipient's final income tax calculation. This interpretation arguably further underscores the separation of the withholding mechanism from the final income determination, with the final return serving to reconcile the correctly applied withholding with the overall actual tax liability.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1992 decision in this case provides a fundamental clarification regarding the distinct spheres of the income tax withholding system and the final self-assessment tax return process in Japan. It establishes that taxpayers cannot use their final tax returns to directly obtain refunds from the State for amounts they believe were erroneously over-withheld by their employers. Such discrepancies must be resolved through the specific legal channels governing the withholding system, primarily involving interactions between the employer and the tax authorities, or directly between the employer and the employee. The final tax return's purpose, in this context, is to allow a credit for tax that was, or should have been, duly and properly withheld under the law, not to serve as a general mechanism for correcting errors committed by third-party withholding agents.