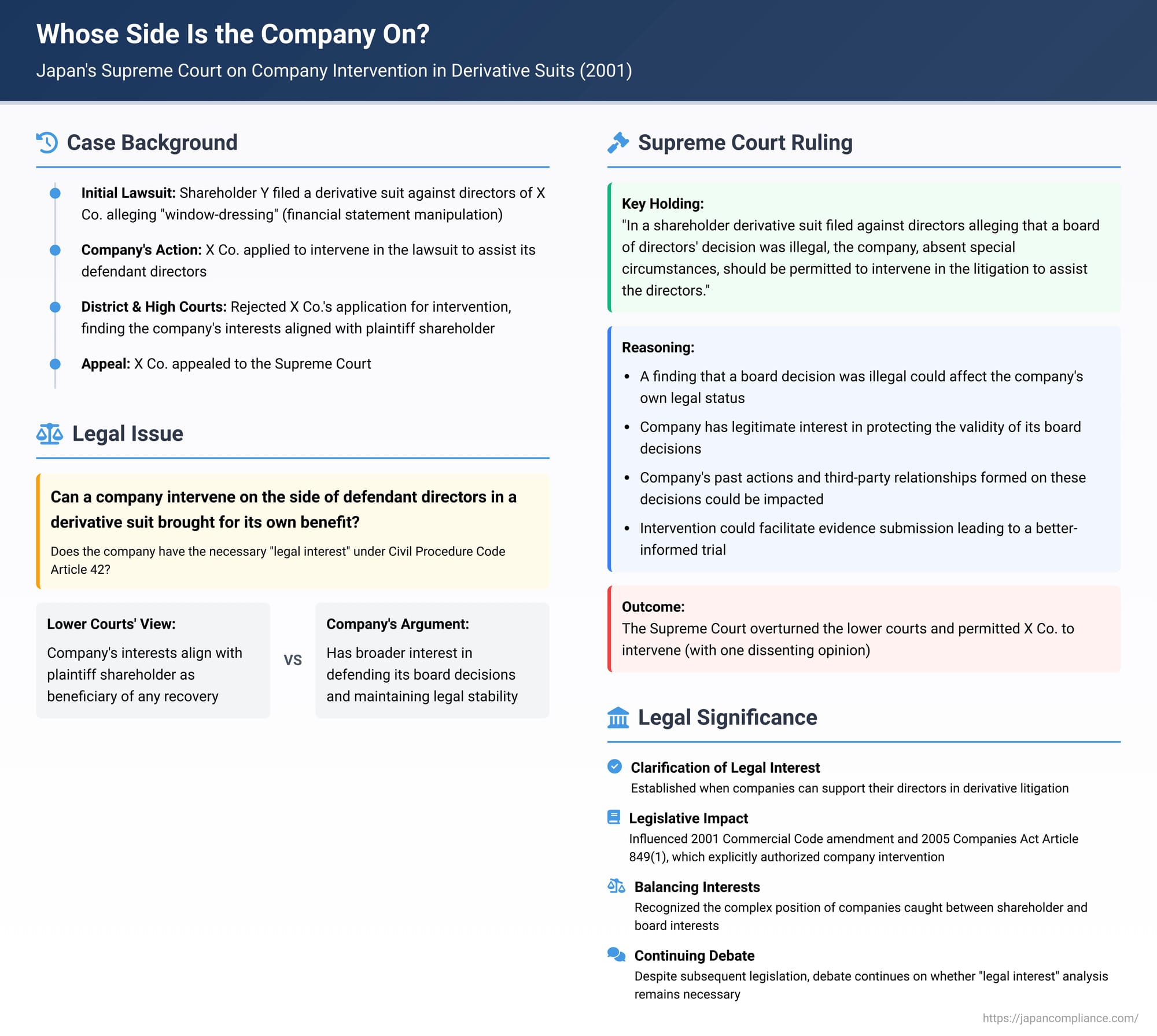

Whose Side Is the Company On? Japan's Supreme Court on Company Intervention in Derivative Suits

Date of Judgment: January 30, 2001

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Introduction

Shareholder derivative suits are a cornerstone of corporate accountability, allowing shareholders to sue company directors (or other liable parties) on behalf of the company for harm caused to it by the directors' misconduct. The lawsuit is nominally brought by the shareholder, but the company is the true plaintiff in interest and the ultimate beneficiary of any successful recovery. This raises a fascinating and somewhat paradoxical question: If the company is the real beneficiary, can it then intervene in the lawsuit to assist the defendant directors against whom the suit is brought?

This issue, touching upon the nature of "legal interest" in litigation and the complex role of a company caught between its shareholders and its management, was addressed by the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan in a significant decision on January 30, 2001.

The Nature of Shareholder Derivative Suits and Auxiliary Intervention

Understanding this case requires a brief look at two key legal concepts in Japanese civil procedure:

- Shareholder Derivative Suits: When company directors breach their duties and harm the company, the company itself has the primary right to sue them. However, if the board (often composed of the alleged wrongdoers or their colleagues) fails or refuses to initiate such a suit, shareholders can step in. A shareholder derivative suit allows a shareholder to "derive" the company's right to sue and pursue the claim against the directors in the company's name and for its benefit. Any damages recovered typically go to the company, not directly to the suing shareholder.

- Auxiliary Intervention (補助参加 - hojo sanka): Under Article 42 of Japan's Code of Civil Procedure, a third party who has a "legal interest" (法律上の利害関係 - hōritsujō no rigai kankei) in the outcome of a pending lawsuit may intervene to assist one of the existing parties. A mere factual or economic interest is generally insufficient; the judgment in the main lawsuit must have the potential to directly affect the intervening party's own legal status or legal rights and obligations.

The central question in the X Co. case was whether a company could demonstrate the requisite "legal interest" to support its defendant directors in a suit brought for its own benefit by one of its shareholders.

The X Co. Case: A Contentious Intervention

The dispute arose as follows:

- Mr. Y, a shareholder of X Co., filed a shareholder derivative suit against several of X Co.'s directors. The lawsuit alleged that these directors had breached their duty of loyalty to X Co. through various actions, including allegedly instructing or overlooking the "window-dressing" (粉飾決算 - funshoku kessan, manipulation of financial statements to show a more favorable position) of the company's financial statements for its 48th and 49th fiscal years. This misconduct, Mr. Y claimed, led X Co. to suffer damages, such as overpaying corporate taxes, incurring unnecessary fees for financial inspectors, and making improper dividend payments.

- In response to this derivative suit, X Co. itself applied to the court for permission to intervene as an auxiliary party. However, X Co. did not seek to support the shareholder plaintiff (Mr. Y); instead, it sought to intervene on the side of, and in assistance to, its defendant directors.

- The shareholder plaintiff, Mr. Y, objected to the company's intervention.

- The Lower Courts' Position: Both the District Court and the High Court rejected X Co.'s application for auxiliary intervention. Their reasoning was that in a derivative suit, the company is the ultimate beneficiary of a successful claim against the directors. Therefore, the company's substantive legal interests were aligned with the plaintiff shareholder and directly opposed to those of the defendant directors. Allowing the company to assist the directors would create a contradictory situation where the company would effectively be arguing against its own potential recovery. This, the lower courts felt, was contrary to the fundamental structure of civil litigation.

X Co. appealed this refusal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision (January 30, 2001)

The Supreme Court, in a majority decision (with one dissenting Justice), overturned the lower courts' rulings and permitted X Co. to intervene on behalf of its defendant directors.

Reaffirming the "Legal Interest" Requirement for Intervention

The Court began by reiterating the established principle that auxiliary intervention under Article 42 of the Code of Civil Procedure is permissible only when the prospective intervenor has a "legal interest" in the outcome of the main lawsuit. This means the judgment in the lawsuit must have the potential to directly affect the intervenor's own legal status or legally recognized interests. A mere factual or indirect commercial interest is not sufficient.

When Can a Company Assist Its Defendant Directors in a Derivative Suit?

The core of the Supreme Court's ruling lay in its analysis of when a company possesses such a "legal interest" to support its directors against a derivative claim. The Court drew a key distinction:

- The decision focused on derivative suits where the central allegation involves the illegality of a formal decision of the board of directors, as opposed to cases based solely on an individual director's personal misconduct or unauthorized actions that were not part of a collective board decision.

- The Court held that: "In a shareholder derivative suit filed against directors alleging that a board of directors' decision was illegal, the company, absent special circumstances, should be permitted to intervene in the litigation to assist the directors."

The Rationale: Protecting the Company's Broader Legal and Operational Interests

The Supreme Court provided the following reasoning for this conclusion:

- Impact on the Company's Legal Position: If a derivative suit succeeds, and directors are held liable because a formal decision made by the company's board of directors is deemed illegal, this judicial finding can have wider repercussions for the company itself. The company's own legal status, its past actions undertaken based on that board decision, and its legal relationships with third parties (formed on the premise of that decision's validity) could all be adversely affected.

- Company's Interest in Upholding Board Decisions: Therefore, the company has a legitimate "legal interest" in preventing a judicial determination that its board's decision was illegal. This interest aligns with supporting the directors who are defending the legality and propriety of that board decision.

- Other Considerations: The Court also mentioned that the decision by the company (presumably by its current management) whether to remain neutral or to intervene to assist the defendant directors is, in itself, a form of management judgment related to how the company responds to allegations concerning director responsibility. Allowing such intervention would not necessarily harm legitimate shareholder interests or compromise the fairness of the litigation process. Furthermore, the company's participation could be beneficial by facilitating the submission of relevant evidence and materials from the company's perspective, potentially leading to a more thorough and well-informed trial.

Application to the X Co. Case

In X Co.'s situation, the allegations of instructing or overlooking window-dressed financial statements directly implicated decisions at the board level, as financial statements require the board's approval under the Commercial Code (then Article 281). If these board decisions were found to be illegal and resulted in the directors being held liable, this finding could significantly affect X Co.'s past financial records and potentially its current or future business relationships and credibility. The Supreme Court found no "special circumstances" that would bar X Co.'s intervention in this instance.

Outcome: The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and the original trial court's decision (which had also rejected intervention). It formally permitted X Co. to intervene in the derivative lawsuit to assist its defendant directors. (It's important to note that this was not a unanimous decision; Justice Machida Akira dissented, arguing that the company's interests are fundamentally opposed to those of the defendant directors in a derivative suit and that the alleged benefits of intervention were not compelling enough to override this structural conflict.)

Significance and Subsequent Developments

The 2001 Supreme Court decision was a significant development in the law governing shareholder derivative suits in Japan.

- Clarification on a Contentious Procedural Point: It provided much-needed (though not universally agreed-upon) clarification on whether and when a company could intervene on the side of defendant directors. The ruling favored allowing intervention, at least in cases where the legality of formal board decisions was central to the derivative suit's claims.

- Addressing the Apparent Paradox: The decision grappled with the apparent paradox of a company assisting directors in a lawsuit that, if successful, would result in a financial recovery for the company. The Supreme Court's reasoning prioritized the company's broader legal interest in the stability and perceived legality of its formal board decisions over the direct financial outcome of the specific derivative claim.

- Legislative Changes Following the Ruling: The legal landscape concerning company intervention in derivative suits evolved after this 2001 Supreme Court decision:

- Later in 2001, the Commercial Code was amended (former Article 268, Paragraph 8) to explicitly establish procedures for a company's auxiliary intervention in derivative suits.

- Subsequently, when the new Companies Act was enacted in 2005, it included an express provision (Article 849, Paragraph 1) stating that the company can intervene as an auxiliary party in a derivative suit.

- Ongoing Debate Regarding "Legal Interest" Post-Legislation: As the PDF commentary accompanying this case highlights, these legislative changes have sparked a new debate about their interplay with the 2001 Supreme Court decision and the underlying "legal interest" requirement from the Code of Civil Procedure:

- View 1: Some argue that the explicit statutory permission in the Companies Act now allows the company to intervene on the directors' side as a matter of course, regardless of a separate "legal interest" analysis under the Code of Civil Procedure. If this view prevails, the specific reasoning of the 2001 Supreme Court decision on why intervention is permissible might become less critical, as the statute itself grants the right.

- View 2 (considered a strong view by some commentators): Others contend that even with the explicit provision in the Companies Act, the fundamental requirement of demonstrating a "legal interest" as stipulated by the Code of Civil Procedure might still need to be satisfied, or at least considered, as the Companies Act does not explicitly state that this general procedural requirement is waived. If this latter view is correct, then the Supreme Court's 2001 detailed reasoning on what constitutes such a legal interest for the company remains highly relevant and influential.

Conclusion

The 2001 Supreme Court decision was a pivotal ruling that, under the legal framework at the time, permitted companies to intervene in shareholder derivative lawsuits to assist their defendant directors, particularly when the core allegations revolved around the legality of formal board of directors' decisions. The Court justified this by reasoning that the company has a vested legal interest in upholding its board's decisions due to the potential wider ramifications for its overall legal status, past actions, and ongoing operations if those decisions are judicially invalidated.

While subsequent legislation has explicitly affirmed a company's general ability to intervene in such suits, the 2001 judgment's detailed analysis of what constitutes a "legal interest" for the company in this complex scenario continues to be a reference point. The case underscores the intricate dynamics and sometimes conflicting interests at play when a company navigates a legal battle initiated by its shareholders against its own management.