Whose Risk Is It Anyway? Japan's Supreme Court on Bank & Developer Duty to Explain in Property Investment Schemes

Judgment Date: June 12, 2006

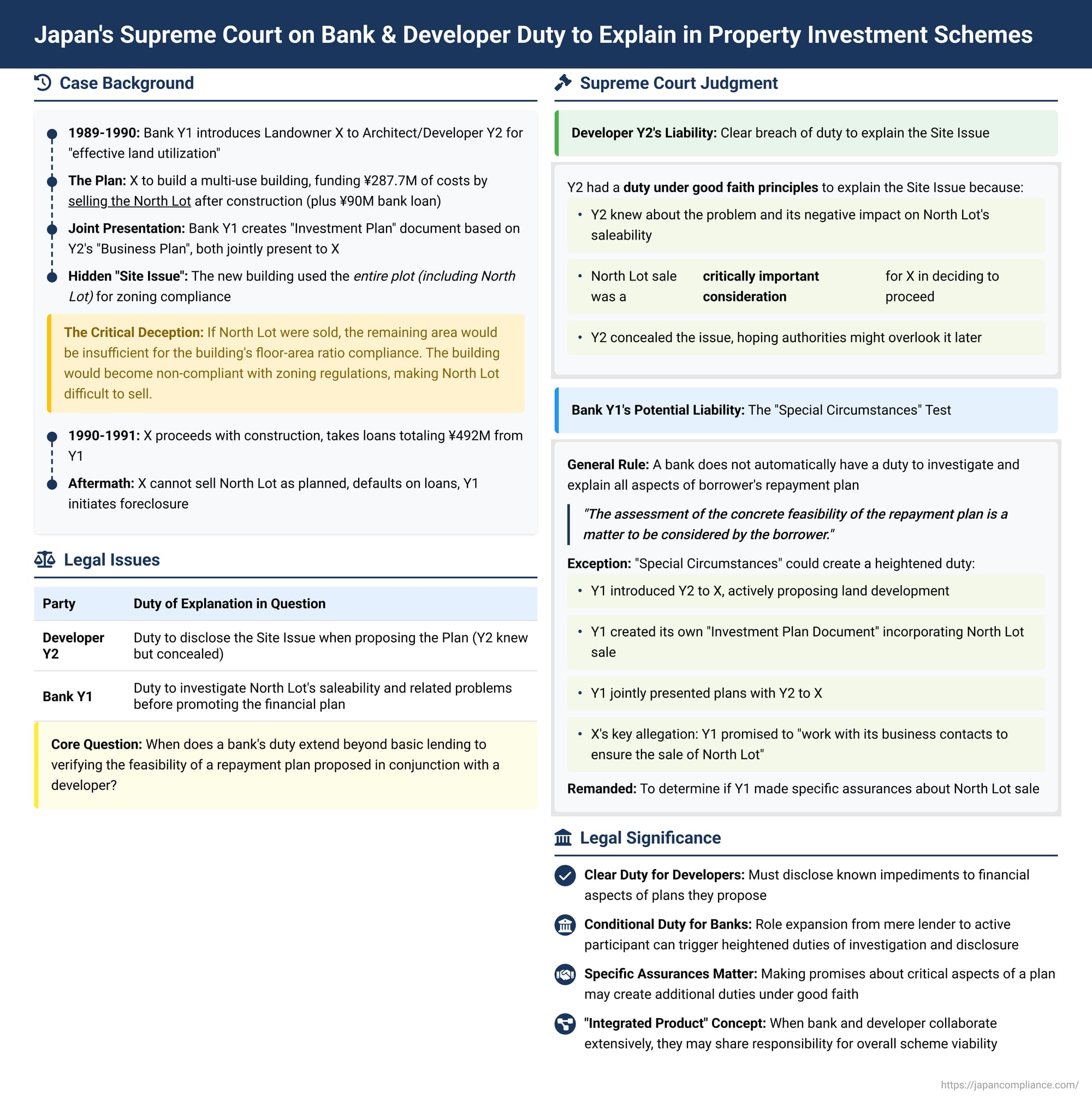

When landowners are approached with proposals for complex property development and financing schemes, they often rely heavily on the expertise and representations of the professionals involved, such as architects, construction companies, and banks. But what happens when a crucial, undisclosed flaw in such a plan leads to significant financial loss for the landowner? A Japanese Supreme Court decision from June 12, 2006 (Heisei 16 (Ju) No. 1219) delved into the extent of the duty of explanation owed by both a bank and an architect/construction company to a landowner in such a scenario, particularly concerning the feasibility of a repayment plan that was central to the entire project.

The Ambitious Development Plan and Its Hidden Flaw

The plaintiff, X, was a landowner who, around 1989, had an existing relationship with Y1 Bank (referred to as Bank A at the time). A representative from Y1 Bank introduced X to Y2 Architect/Construction Company (Y2 Architect), touting Y2 as a company with expertise in effective land utilization.

Around January 1990, Y2 Architect's representative proposed "the Plan" to X. This comprehensive plan involved X demolishing existing structures on his properties ("the Lands") and constructing a new multi-use building ("the Building") comprising X's residence, rental units, and commercial/office spaces. The initial financial projection indicated that X would use his own funds of approximately ¥287.7 million, supplemented by a bank loan of ¥90 million. A key component of this self-funding strategy was that the ¥287.7 million would be raised by selling a northern portion of X's land (referred to as "the North Lot") for around ¥300 million after the new Building was constructed on the remaining portion of the Lands. Y2 Architect prepared a detailed "Business Plan Document" based on this premise.

Concurrently, Y1 Bank's representative, referencing Y2's Business Plan, created an "Investment Plan Document." This document outlined a specific financial plan, showing how X, using his purported self-funding and the ¥90 million loan from Y1 Bank (totaling ¥377.7 million), could construct the Building and use rental income to service the debt. Representatives from both Y1 Bank and Y2 Architect jointly presented these intertwined plans to X, explaining their contents. This joint explanation reinforced the idea that X's significant financial contribution would come from the sale of the North Lot.

Relying on these presentations and believing the self-funding through the North Lot sale was feasible, X decided to proceed. However, instead of just a ¥90 million loan, X ultimately undertook a much larger borrowing from Y1 Bank to cover the entire construction cost of the Building. In June 1990, X entered into a construction contract with Y2 Architect for a contract price of ¥395 million. The Building was completed and delivered to X in October 1991. Over this period and subsequently for refinancing, Y1 Bank extended loans to X totaling ¥492 million.

The entire project, however, was built on a precarious and undisclosed foundation: "the Site Issue" (本件敷地問題 - honken shikichi mondai). The new Building had received its construction permit based on using all of X's Lands (including the North Lot) as its designated official site. Furthermore, the Building was constructed very close to the maximum allowable floor-area ratio (容積率 - yōsekiritsu) permitted for that entire original site. The critical, undisclosed consequence was that if the North Lot were subsequently sold off as a separate parcel (as the Plan envisioned), the remaining land area allocated to the new Building would become insufficient, rendering the new Building non-compliant with zoning regulations (i.e., it would exceed the permissible floor-area ratio for the smaller, redefined site). Additionally, any potential buyer intending to construct their own building on the purchased North Lot would likely face significant hurdles in obtaining a construction permit. This is because it would constitute a "double use of a site" (敷地の二重使用 - shikichi no nijū shiyō)—attempting to use land already counted towards the zoning compliance of an existing building (X's new Building) as the basis for a new, separate construction. These zoning and regulatory impediments would severely diminish the market value and saleability of the North Lot.

Crucially, Y2 Architect's representative was aware of this Site Issue and its likely negative impact on the North Lot's sale price. Despite this knowledge, Y2 proposed the Plan to X, apparently hoping that the "double use" issue might be overlooked by authorities when a future buyer of the North Lot applied for their own building permit. Y2 Architect did not explain any aspect of the Site Issue or its consequences to X. At the time the Plan was proposed and the initial loans were made, both X and Y1 Bank's representative were unaware of these critical site-related problems.

The Unraveling: Default and Legal Proceedings

After the Building was completed, X found himself unable to sell the North Lot for the anticipated price (or perhaps at all under viable terms) due to the undisclosed Site Issue. Without these proceeds, he could not make the necessary repayments on his substantial loans from Y1 Bank and eventually defaulted. Y1 Bank, which held a mortgage over X's Lands and the new Building, initiated foreclosure proceedings.

Facing this financial ruin, X sued both Y1 Bank and Y2 Architect for damages amounting to ¥339.2 million plus interest. X alleged that their failure to explain the critical Site Issue constituted either a tort or a breach of contractual duty, and that this failure had directly led him to take out the loans and construct the Building, resulting in his substantial losses.

The Osaka District Court (first instance) partially found in favor of X. However, the Osaka High Court (second instance) reversed this, dismissing all of X's claims. The High Court reasoned, among other things, that even with the Site Issue, it was not definitively proven that X could not have raised approximately ¥300 million from the sale of the North Lot. Therefore, it concluded the loan repayment plan was not inherently unfeasible from the outset, and thus Y1 and Y2 did not have a decisive breach of any explanation duty regarding this point. X appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Redefining Duties of Explanation

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's judgment and remanded the case for further proceedings against both Y1 Bank and Y2 Architect, finding that the High Court had erred in its assessment of their respective duties of explanation.

Regarding Y2 Architect/Construction Company's Liability:

The Supreme Court found a clear breach of duty by Y2 Architect.

- The Plan proposed by Y2 heavily relied on the sale of the North Lot as a means for X to contribute his share of the project costs (even if X later borrowed the full amount, this was the initial premise). The feasibility of this sale was, therefore, a "critically important consideration" for X in deciding whether to proceed with Y2's development proposal.

- The Site Issue directly and severely impacted the saleability and value of the North Lot.

- Y2's representative, knowing about the Site Issue and its negative consequences, had a duty under the principle of good faith and fair dealing (信義則 - shingisoku) to explain these problems to X when proposing the Plan.

- Instead, Y2's representative concealed the Site Issue, hoping it might be overlooked by authorities later. This was a clear and actionable breach of Y2's duty of explanation. The Supreme Court concluded that Y2 was liable for the damages X suffered as a result of this breach. The High Court's dismissal of the claim against Y2 was thus found to be an error of law.

Regarding Y1 Bank's Liability – The "Special Circumstances" Test:

The Supreme Court's assessment of Y1 Bank's liability was more nuanced.

- General Principle for Lenders: The Court acknowledged that, as a general rule, when a bank provides a loan, the assessment of the "concrete feasibility of the repayment plan is a matter to be considered by the borrower." A bank does not automatically have a duty to investigate and explain all aspects of a borrower's repayment strategy, such as the saleability of an asset like the North Lot.

- Potential for "Special Circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō) to Create a Heightened Duty: However, the Supreme Court stated that if "special circumstances" exist, a duty for the bank's representative to investigate the North Lot's saleability (including the Site Issue) and to explain these matters to X could be affirmed under the principle of good faith. The Court identified several factors already established in the case that pointed towards such heightened involvement by Y1 Bank:

- (i) Y1 Bank did not merely act as a passive lender. Its representative introduced Y2 Architect to X, actively proposing the idea of developing X's land for effective utilization.

- (ii) Y1 Bank's representative created its own "Investment Plan Document" based on Y2's Business Plan. This bank-created document also incorporated the premise of selling the North Lot to generate funds for X's (initial) equity contribution to the project.

- (iii) Y1 Bank's representative, jointly with Y2's representative, presented and explained these integrated plans to X.

- (iv) X proceeded with the substantial loan from Y1 Bank and the construction contract with Y2 Architect in reliance on these joint explanations, believing the overall repayment plan, hinging on the sale of the North Lot, was feasible.

- The Crucial Unverified Assertion by X: Beyond these established facts, X had specifically alleged that during these discussions, Y1 Bank's representative had gone further and stated that the bank would "even work with its business contacts to ensure the sale of the North Lot."

- Remand for Y1 Bank: The Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred by dismissing the claim against Y1 Bank without adequately considering whether these "special circumstances," particularly X's assertion about the bank's specific assurance regarding the sale of the North Lot, were present and proven. The Supreme Court ruled that if this specific assurance by the bank's representative was proven true, then it could give rise to a duty under good faith for Y1 Bank to investigate the North Lot's true saleability (which would involve discovering and disclosing the Site Issue) and to fully explain any problems to X. Because the High Court had not made a factual determination on this critical assertion, the case against Y1 Bank was remanded for it to do so.

Analyzing the Scope of Explanation Duties for Banks and Developers

This Supreme Court judgment offers important insights into the duties of professionals involved in promoting complex development and financing schemes:

- Clear Duty for Developers/Architects: When a developer or architect like Y2 proposes a plan that relies on certain financial outcomes (like the sale of property at a certain price), they have a strong duty under good faith to disclose any known material facts that could undermine the feasibility of that plan. Concealing known critical impediments, such as zoning problems that would devalue a property intended for sale, is a clear breach of this duty.

- Conditional Duty for Banks: A bank's role as a mere lender does not automatically saddle it with a duty to vet every aspect of a borrower's business plan. However, this changes when the bank steps beyond passive lending and becomes an active participant in the formulation, promotion, and, crucially, the assurance of key components of that plan.

- Deep Involvement: Factors like introducing the developer, co-creating investment plans, and jointly presenting the scheme to the client can shift the bank's role and responsibilities.

- Specific Assurances: If a bank representative makes specific promises or assurances about facilitating critical parts of the borrower's financial plan (e.g., ensuring a property sale), this can trigger a heightened duty of care, including a duty to investigate and disclose known or reasonably discoverable risks related to that assurance. This moves the bank's role closer to that of an advisor.

- The "Integrated Product" Concept: The case illustrates a scenario where a property development and its financing were presented to the client as a closely linked, almost "integrated product." In such situations, where the bank and developer collaborate extensively, there's a stronger argument that they may share a degree of responsibility for the overall viability and transparent presentation of the entire scheme, not just their isolated components. A bank cannot easily disclaim responsibility for problems in a plan it actively helped create and promote to its client.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2006 decision in this case underscores that while borrowers bear primary responsibility for their financial decisions, professionals who propose and facilitate complex investment and development schemes also carry significant duties of explanation and care. Developers must be transparent about known material risks in their proposals. Banks, while not generally responsible for vetting every detail of a borrower's plan, may acquire a heightened duty to investigate and disclose when they become deeply involved in crafting and promoting that plan, especially if they provide specific assurances about its key financial outcomes. This ruling serves as a reminder of the importance of diligence, transparency, and good faith in dealings involving substantial financial commitments and complex property development projects.