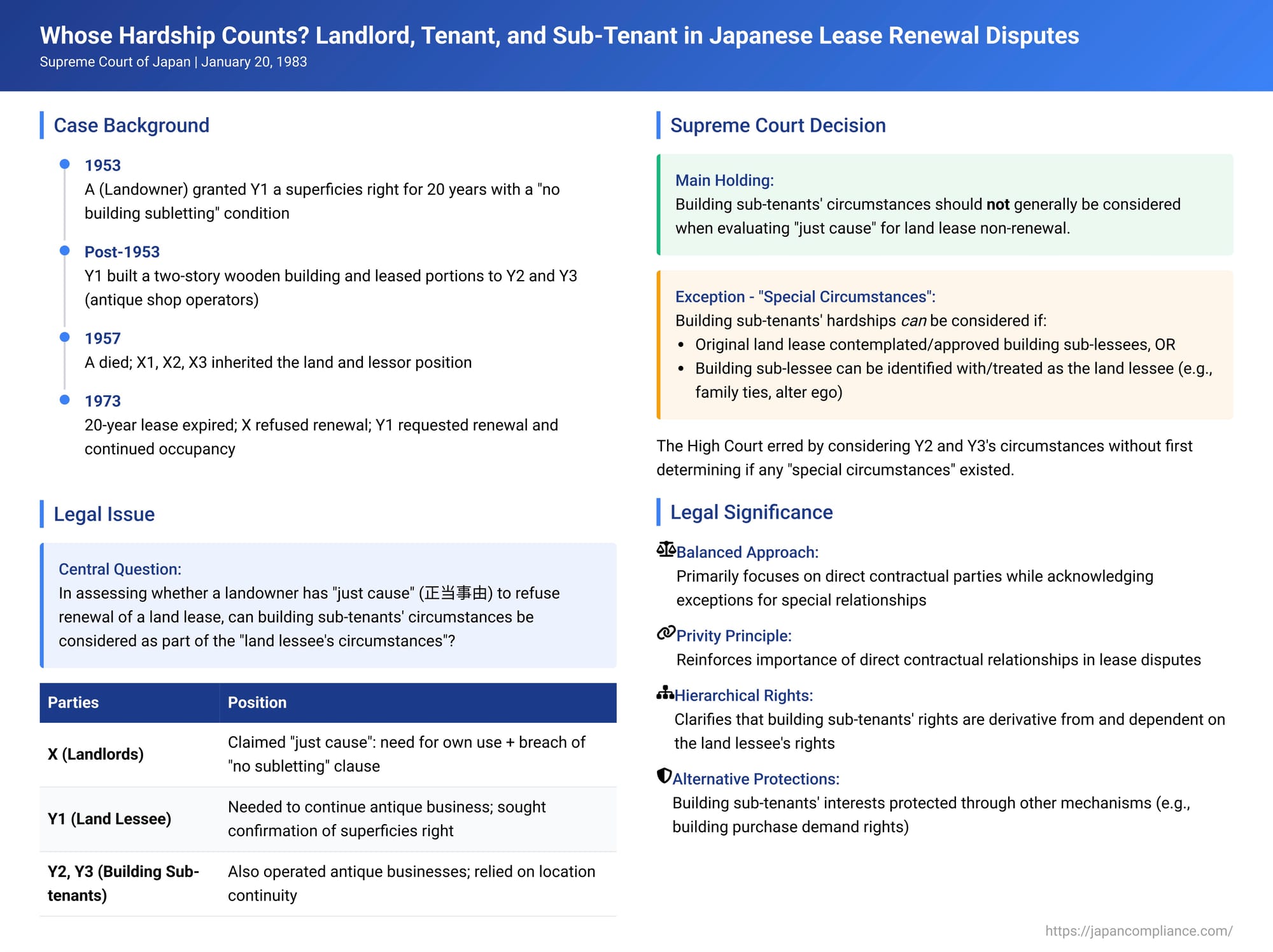

Whose Hardship Counts? Landlord, Tenant, and Sub-Tenant in Japanese Lease Renewal Disputes

Date of Judgment: January 20, 1983

Case Name: Claim for House Removal and Land Surrender (Main Suit), Claim for Confirmation of Superficies Right (Counterclaim)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Introduction

Lease renewals in Japan, particularly for land used for building ownership, are governed by principles designed to protect tenants from arbitrary eviction. A cornerstone of this system is the "just cause" (seitō jiyū) requirement: a landlord wishing to refuse a lease renewal at the end of its term must demonstrate valid reasons for needing the land back. A Supreme Court decision from January 20, 1983, delved into a particularly complex facet of this rule: when the building on the leased land is itself sub-leased to other parties, whose circumstances should be considered in the "just cause" calculation? Does the hardship faced by these building sub-tenants weigh in the balance?

A Multi-Generational Lease and Its Occupants: The Factual Matrix

The dispute arose from the following set of facts:

- The Original Lease and Building: In 1953, A, a landowner, granted a superficies right (chijōken – a strong, long-term land lease right) to Y1 for a 20-year term. The purpose was for Y1 to own a building on this "Subject Land." The agreement included a special condition prohibiting Y1 from subletting the building to be constructed. Y1 subsequently built a two-story wooden structure (the "Subject Building"), which served as both a residence and a commercial shop.

- Sub-Tenancies: Y1 then leased portions of this Subject Building to Y2 and Y3. Y1's wife, along with Y2 and Y3, each operated separate antique shops on the ground floor of the building.

- Change in Landlord: A, the original landowner, passed away in 1957. The Subject Land, along with A's position as lessor, was inherited by X1, X2, and X3 (collectively "X").

- Lease Expiry and Dispute: As the 20-year lease term approached its end in 1973, X notified Y1 in writing of their refusal to renew the land lease. Y1, however, formally requested a renewal and continued to occupy and use the Subject Land even after the original term expired.

- Litigation and "Just Cause": X initiated legal proceedings against Y1, seeking the cancellation of Y1's superficies registration, the removal of the Subject Building, and the surrender of the Subject Land. X also sued the building sub-tenants, Y2 and Y3, demanding their eviction from the Subject Building.

The central legal battleground was whether X had sufficient "just cause" to refuse the lease renewal, as required by the then-applicable Land Lease Act (旧借地法 - Kyū Shakuchi Hō).- X's Arguments for Just Cause: X claimed a pressing need for the Subject Land for their own use. Their existing residence and shop on an adjacent property were purportedly too small, and one of the X parties (X2) intended to start an independent business on the Subject Land. X also pointed to Y1's alleged breach of the "no building subletting" clause in the original lease and mentioned an offer of monetary compensation (a common factor in "just cause" assessments) made during the litigation.

- Y1's Position: Y1, along with Y2 and Y3, argued for the necessity of continuing their antique businesses in the Subject Building and, in a counterclaim, sought legal confirmation of Y1's superficies right.

- Lower Court Rulings: Both the first instance court and the High Court ruled against X, finding that X lacked the requisite "just cause" to refuse the lease renewal. Significantly, the High Court, in its decision, explicitly stated that it had considered "the circumstances of the land lessee side, including the building sub-lessees (Y2 and Y3)" in reaching its conclusion. X appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Question at the Forefront

The key question for the Supreme Court was: In assessing whether a landowner has "just cause" to refuse renewal of a land lease (granted for building ownership), is it permissible to take into account the circumstances and hardships of tenants who lease the building from the land lessee, as part of the overall "land lessee's circumstances"?

The Supreme Court's Decision and Reasoning

On January 20, 1983, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court quashed the High Court's decision and remanded the case for reconsideration. The Supreme Court laid out the following principles:

- General Standard for "Just Cause": The Court reaffirmed the established rule (citing a 1962 Grand Bench decision) that determining "just cause" involves a comparative balancing of the circumstances and needs of the landowner against those of the land lessee.

- Considering Building Sub-Lessees' Circumstances – The "Special Circumstances" Exception: The Supreme Court held that when evaluating the "land lessee's circumstances," the personal circumstances of those who are merely tenants of the building on the leased land (i.e., building sub-lessees) should not generally be taken into account.

However, the Court carved out an exception: the building sub-lessees' circumstances can be considered if "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō) are found to exist. The Court provided examples of such "special circumstances":- The original land lease agreement, from its inception, contemplated or explicitly approved the existence of building sub-lessees.

- The building sub-lessee can, in reality, be identified with or treated as effectively the same as the land lessee (e.g., due to close family ties or situations where the sub-lessee is an alter ego of the land lessee, like a personally controlled company).

- Impermissibility Absent Special Circumstances: If such "special circumstances" are not present, then it is impermissible to factor in the building sub-lessees' hardships or needs when weighing the "land lessee's circumstances" against the landowner's. The Court cited a 1981 Third Petty Bench decision supporting this restrictive approach.

- High Court's Error: The High Court had erred because it took into account the circumstances of Y2 and Y3 (the building sub-lessees) without first determining whether any "special circumstances" linking them to the land lease or to Y1 (the land lessee) existed. The case was sent back to the High Court to re-evaluate the "just cause" issue, applying this more precise legal standard.

Dissecting "Just Cause" and the Role of Different Parties

This Supreme Court decision offers crucial insights into the nuanced application of the "just cause" principle in Japanese lease law.

The General Exclusion of Building Sub-Tenant Circumstances

The principle that, generally, only the direct land lessee's situation is weighed against the landowner's in a land lease renewal dispute is significant. This approach (largely affirmed by subsequent legal developments, including the current Land and Building Lease Act, which details factors for just cause in its Article 6) is supported by several rationales:

- Lack of Privity: Building sub-tenants (like Y2 and Y3) are not parties to the land lease agreement between the landowner (X) and the land lessee (Y1). Their contractual relationship is with Y1, the owner of the building.

- Landowner's Lack of Control: The landowner typically has no say in who the land lessee chooses as tenants for the building, unlike a land sub-lease (a sub-lease of the land itself), which usually requires the landowner's consent. To allow the circumstances of these third-party building occupants to dictate the continuation of the underlying land lease could expose the landowner to unforeseen burdens and extended lease periods due to individuals with whom they have no direct dealing.

- Derivative Rights: The rights of building sub-tenants are inherently dependent on the land lessee's right to maintain the building on the land. If the land lessee's right to use the land ends, the derivative rights of the building occupants are consequently affected.

- Alternative Protections: The legal system provides other potential avenues for protecting building sub-tenants, typically at a later stage, if the land lease is indeed terminated and the building's fate is decided (e.g., through the land lessee's right to demand the landowner purchase the building).

Arguments for Considering Building Sub-Tenants (and the "Special Circumstances" Rationale)

While the general rule excludes building sub-tenants' circumstances, the Supreme Court's "special circumstances" exception acknowledges situations where a stricter separation would be unjust or ignore the realities of the arrangement:

- De Facto Land Users: Building sub-tenants are, in a practical sense, users of the land, and the termination of the land lease often directly leads to their displacement.

- Foreseeability by Landowner: In some cases, particularly with commercial properties, landowners might lease land with the clear understanding or expectation that the building constructed will be used by multiple tenants.

- The first type of "special circumstance" – where the original land lease contemplated or approved building sub-lessees – addresses this. This likely means more than a landowner's vague awareness that a building might be partly tenanted. It points to scenarios where the land was leased specifically for a building designed for subletting (e.g., an apartment complex, a shopping arcade). The existence of a "no building sublet" clause in the original lease between A and Y1 in this specific case would be a strong factor against finding this type of special circumstance.

- The second type – where the building sub-lessee is effectively identical to the land lessee – covers situations where treating them separately would be artificial. This could involve close family members using different parts of a family-owned building or a business owner leasing land and then having their own operating company (as a building sub-lessee) use the premises. Here, the hardship of the building sub-lessee is, in essence, the hardship of the land lessee.

Protection of Building Sub-Tenants if the Land Lease Terminates

The Supreme Court's ruling does not mean building sub-tenants are left completely unprotected if the land lease ends. Instead, their protection is often addressed through subsequent mechanisms:

- Building Purchase Demand Right (Tatemono Kaitori Seikyūken): Under Japanese law (currently Article 13 of the Land and Building Lease Act), if a land lease for building ownership expires and is not renewed, the land lessee can demand that the landowner purchase the building at fair market value. If the landowner purchases the building, they may also take over existing leases with the building tenants. At this stage, the circumstances of the building tenants (now direct tenants of the landowner) would become directly relevant to the continuation or termination of their building leases.

- Some legal scholars argue that if the land lessee fails to exercise this building purchase demand right, building sub-tenants should, in some cases, be allowed to exercise it subrogatively to protect their occupancy, though case law has generally been hesitant to affirm such a right directly for building sub-tenants.

Conclusion

The 1983 Supreme Court decision illustrates the careful balancing act inherent in Japan's "just cause" system for lease renewals. It clarifies that while the primary focus is on the landowner and the direct land lessee, the complex realities of property use, especially involving sub-tenancies within buildings on leased land, necessitate a nuanced approach. The "special circumstances" doctrine allows courts to look beyond formal contractual lines in specific, justifiable situations. For landlords, tenants, and their legal advisors, this case underscores the importance of clearly defining intentions and relationships at the outset of a land lease, particularly if subletting of any form is anticipated, and understanding the specific, limited conditions under which the needs of building occupants might influence the fate of the underlying land lease.