Whose Fault Is It Anyway? A 1929 Japanese Ruling on Liability for 'Performance Assistants' in Contracts

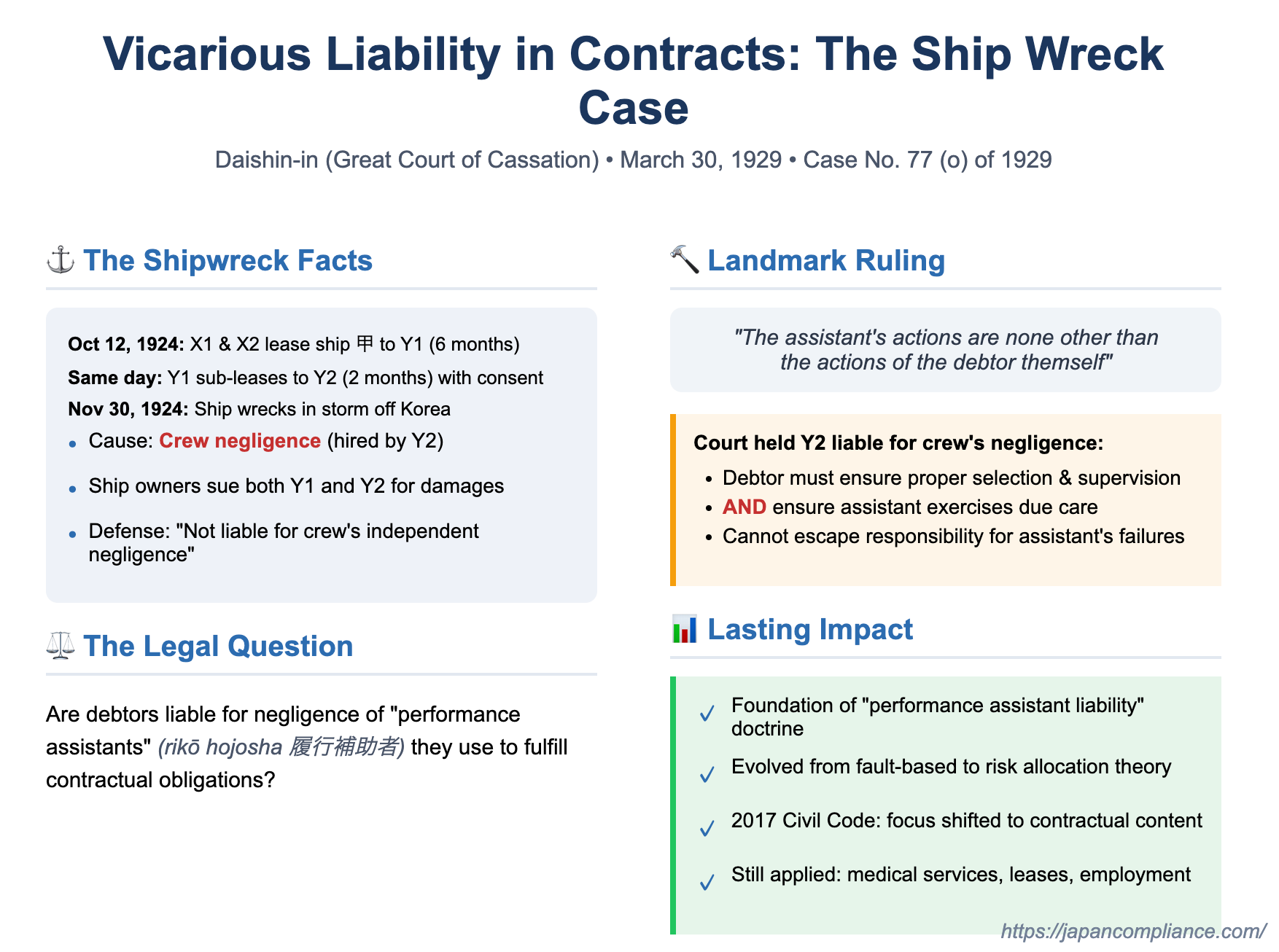

Date of Judgment: March 30, 1929

Case: Daishin-in (Great Court of Cassation), Third Civil Affairs Department, Case No. 77 (o) of 1929 (Damages Claim Case)

In the world of contracts, parties often rely on others—employees, agents, or subcontractors—to help fulfill their obligations. These individuals or entities are sometimes referred to in legal terms as "performance assistants" (履行補助者 - rikō hojosha). A critical legal question that arises is: if a performance assistant acts negligently or improperly, causing a breach of the original contract, is the primary contracting party (the debtor) responsible for the assistant's failings? This principle, akin to vicarious liability within a contractual context, was the subject of a foundational ruling by Japan's Daishin-in (Great Court of Cassation), the highest court at the time, on March 30, 1929.

The Wrecked Ship: Facts of the Case

The plaintiffs, X1 and X2, were co-owners of a motorized sailing ship named 甲 (pronounced "Kō"). On October 12, 1924, they entered into a lease agreement, renting the ship 甲 to Y1 (one of the defendants and appellants) for a period of six months. On that very same day, Y1, having obtained the consent of X1 and X2, sub-leased the ship 甲 to Y2 (also a defendant and appellant) for a shorter period of two months.

Tragedy struck on November 30, 1924. While being operated by a crew hired by the sub-lessee Y2, the ship 甲 encountered a violent storm off the coast of Keishōhoku-dō, Korea (under Japanese administration at the time). The ship ran aground and was wrecked, making it impossible for Y1 or Y2 to return it to its owners, X1 and X2.

X1 and X2 subsequently filed a lawsuit against both Y1 (the original lessee) and Y2 (the sub-lessee), claiming damages for the loss of their ship. They alleged that the shipwreck was directly attributable to the negligence of the ship's crew, who were in the employ of Y2. Y1 and Y2, in their defense, argued that a debtor (or an employer) should only be held liable for non-performance stemming from an employee's negligence if there was a specific legal provision mandating such liability, or if the employer themselves had been negligent in the selection or supervision of that employee. They essentially denied automatic responsibility for the operational negligence of the crew hired by Y2.

The High Court, which heard the case before it reached the Daishin-in, found in favor of X1 and X2, at least in part. It held Y2 (the sub-lessee) directly liable to the original lessors (X1 and X2) based on Article 613, paragraph 1, of the Civil Code, which stipulates that if a lessee lawfully sub-leases the leased object, the sub-lessee assumes direct responsibility towards the lessor. The defendants then appealed to the Daishin-in.

The Legal Principle at Stake: Vicarious Liability in Contract

Under the old Japanese Civil Code (in force at the time of this case), liability for non-performance of a contractual obligation generally required "grounds attributable to the debtor" (旧民法415条 - old Civil Code Article 415). This phrase was commonly interpreted to mean the debtor's own intention or negligence (fault). The core question for the Daishin-in was whether a debtor was responsible for the faults committed by third parties they utilized in the course of performing their contractual duties, even if the debtor themselves was not personally negligent in choosing or overseeing those third parties.

The Daishin-in's Landmark Decision: Debtor is Responsible for Assistant's Negligence in Performance

The Daishin-in dismissed the appeal by Y1 and Y2, thereby upholding their liability. The Court laid down a clear principle regarding the responsibility of a debtor for the actions of their performance assistants:

The Court reasoned that a person who undertakes an obligation (a debtor) is bound by contract or law to perform the required act of prestation (the performance owed) with a certain standard of care. Whether the debtor has fulfilled this duty of care in the performance of the obligation is determined by looking at the conduct of whomever is actually carrying out the performative acts.

Therefore, the Court stated, when a debtor employs another person (a performance assistant) to fulfill their obligation:

- The debtor is, of course, required to be free from negligence in the selection and supervision of that assistant.

- Beyond this, and crucially, within the scope of using that other person to effect the performance of the obligation, the debtor cannot escape responsibility for ensuring that the assistant exercises the necessary care that should accompany such performance.

- The debtor, as the employer or user of the assistant, cannot evade any responsibility for the consequences arising from the assistant's lack of care in the course of that performance.

The Daishin-in articulated the fundamental basis for this rule: "...the debtor is attempting to fulfill their obligation by utilizing the actions of the assistant, and within this scope, the assistant's actions are none other than the actions of the debtor themself."

Thus, since the lower court had found that the crew of the ship 甲 (employed by Y2) had acted negligently in the performance of the obligations related to the ship (which implicitly included its safe operation and eventual return), the Daishin-in found it appropriate to hold Y2, as the employer and debtor (sub-lessee), responsible for that negligence.

Unpacking the "Performance Assistant Liability" Doctrine

This 1929 decision is a cornerstone in Japanese law for establishing what came to be known as "performance assistant liability" (rikō hojosha sekinin). It made it clear that a debtor generally cannot use third parties to perform their contractual duties and then wash their hands of responsibility if those third parties perform defectively or negligently.

- Broad Implication: The core idea is that if a debtor chooses to use an assistant to meet their contractual commitments, they remain answerable for the quality and diligence of that performance. The assistant, in effect, becomes an extension of the debtor for the purpose of fulfilling the obligation.

- Evolution of Legal Thought in Japan:

- Traditional View: Following this and similar Daishin-in rulings (e.g., another in 1929 holding a lessee liable for a consented sub-lessee's negligence causing a fire ), the traditional academic view often defined the "grounds attributable to the debtor" (for contractual liability) to include not only the debtor's own intent or negligence but also "grounds equivalent thereto under the principle of good faith," into which the intent or negligence of a performance assistant was placed. This view sometimes distinguished between "true performance assistants" (for whose fault the debtor was always liable) and "performance deputies" (e.g., a sub-agent appointed with permission), where it was argued the debtor might only be liable for fault in selection or supervision, drawing analogies from specific articles in the old Civil Code like Article 105 (on sub-agency) or Article 658(2) (on a mandatary's liability for a sub-mandatary). This distinction led to criticism of judgments that held original lessees broadly liable for the negligence of sub-lessees to whom the lessor had consented.

- Expansion Rationale (Risk Allocation): Later, influential legal scholars argued for reconstructing performance assistant liability not merely as an imputation of fault, but as a principle based on risk allocation. The reasoning was that a debtor who uses performance assistants expands their own sphere of activity and potential profit, and therefore should justly bear the risks associated with using those assistants, even if the debtor had no direct control over the assistant's specific negligent act. This view emphasized that such liability should cover not only employee-like assistants (comparable to tort vicarious liability under Civil Code Article 715) but also assistants who operate more independently, like contractors (comparable to a principal's limited tort liability for contractors under Civil Code Article 716).

- Modern Critique and Focus on Contractual Content: More recent academic critiques have shifted the focus. These views suggest that the older approaches were too wedded to the idea that fault (negligence) was the primary basis for contractual liability, thus treating performance assistant liability as an exceptional or special category. Instead, modern analysis tends to argue that contractual liability stems fundamentally from the binding force of the contract itself. Whether a debtor is liable for an assistant's actions should be determined by how those actions relate to the specific content and obligations of the contract agreed upon.

- For "obligations of result" (kekka saimu - where a specific outcome is promised), the question becomes whether the assistant's failure to achieve that result can be excused by any legally recognized grounds (like force majeure).

- For "obligations of means" (shudan saimu - where the debtor promises to use a certain level of skill and care), the inquiry focuses on defining the precise nature of the duty undertaken by the debtor, and then assessing whether the performance, including the actions of any assistant, met that standard of care.

Impact of the 2017 Civil Code Revision

Japan's Civil Code underwent a major revision concerning contract law, effective in 2020 (though the PDF refers to it as the 2017 revision, as the law was passed then).

- No Specific Provision: During the deliberations for this revision, consideration was given to creating an explicit statutory provision on performance assistant liability, but ultimately, no such specific article was enacted. This means the principles governing this area continue to be developed through judicial interpretation and academic theory.

- Shift in Liability Framework: Critically, the revised Civil Code Article 415, paragraph 1, now states that a debtor is excused from liability for non-performance if the non-performance is "due to grounds not attributable to the debtor." The determination of whether grounds are "attributable" is to be made "in light of the contract, other grounds for the obligation, and common sense in transactions (or commercial custom)". This language signals a move away from requiring the creditor to prove the debtor's specific "negligence" in all cases and instead focuses on whether the cause of non-performance is something for which the debtor should bear responsibility under the terms and context of their agreement.

- Undermining of Old Distinctions: The deletion of old Civil Code Articles 105 and 658(2) during the revision has significantly weakened the textual basis for the traditional view that sought to limit a debtor's liability for certain types of legally permitted "performance deputies".

Under this new framework, it becomes more challenging to apply a blanket rule that simply equates an assistant's negligence with the debtor's own negligence for all types of contracts. Instead, the analysis is likely to be more nuanced, focusing on the specific contractual obligations and whether the use of an assistant, and that assistant's subsequent actions, resulted in a failure to deliver the promised performance according to the contract's terms and underlying purpose.

Continuing Relevance of the 1929 Principle in Specific Contexts

Despite the evolution of the Civil Code and legal theory, the core idea expressed by the Daishin-in in 1929—that "within the scope of using that other person to effect performance... the assistant's actions are none other than the actions of the debtor themself"—still holds persuasive power and can be seen reflected in specific areas of law:

- Medical Services: A hospital or medical institution (the debtor providing medical services) is generally held liable for the negligent acts or omissions of the doctors and other medical staff it employs (its performance assistants) if those acts result in harm to a patient. The actions of the medical staff in providing treatment are considered the actions of the hospital itself in fulfilling its contractual or relational duty of care.

- Lease Agreements: A lessee (tenant) is typically responsible for damage caused to the leased property by persons they allow to use the property, such as cohabitants or, as in this 1929 case, consented sub-lessees. The actions of these "occupant assistants" regarding the care and use of the property are often viewed as attributable to the lessee when determining if the lessee has breached their obligation to return the property undamaged or to use it with due care. The lessor's consent to a sub-lease usually only means the prohibition against sub-leasing is waived; it doesn't typically absolve the original lessee (the sub-lessor) of their underlying responsibilities to the original lessor unless specifically agreed.

- Duty of Care for Safety (Anzen Hairyogimu): The application is more complex here. In a 1983 Supreme Court case, where a Self-Defense Forces member was killed due to the negligent driving of a fellow member (the driver being a performance assistant of the State), the Court took a somewhat restrictive view. It held that the State's primary safety duty was to provide a safe working environment (personnel and material) and did not automatically extend to ensuring that every individual employee perfectly adhered to general duties of care, like traffic laws, during routine operations. This decision has been criticized by some scholars who argue for a broader scope of employer responsibility for the safety-related actions of their employees. This illustrates that the extent to which an assistant's specific failure is deemed "the debtor's act" can depend heavily on how the primary debtor's own underlying duty is defined.

Concluding Thoughts

The Daishin-in's 1929 ruling in the case of the wrecked ship was a foundational judgment in Japanese contract law, firmly establishing the principle that a contracting party cannot simply delegate their duties to others and thereby escape responsibility for how those duties are ultimately performed. While the theoretical framework for understanding this "performance assistant liability" and the broader Civil Code provisions on contractual liability have evolved significantly over the nearly a century since this decision, its core message remains highly relevant. A party that chooses to use others to fulfill its contractual promises is generally answerable for the failures of those assistants in delivering the agreed-upon performance. The modern approach, particularly under the revised Civil Code, tends to frame this responsibility less in terms of imputing an assistant's "fault" to the principal debtor, and more by examining whether the overall performance rendered, including the assistant's contribution, met the standards and obligations set out in the specific contract between the original parties.