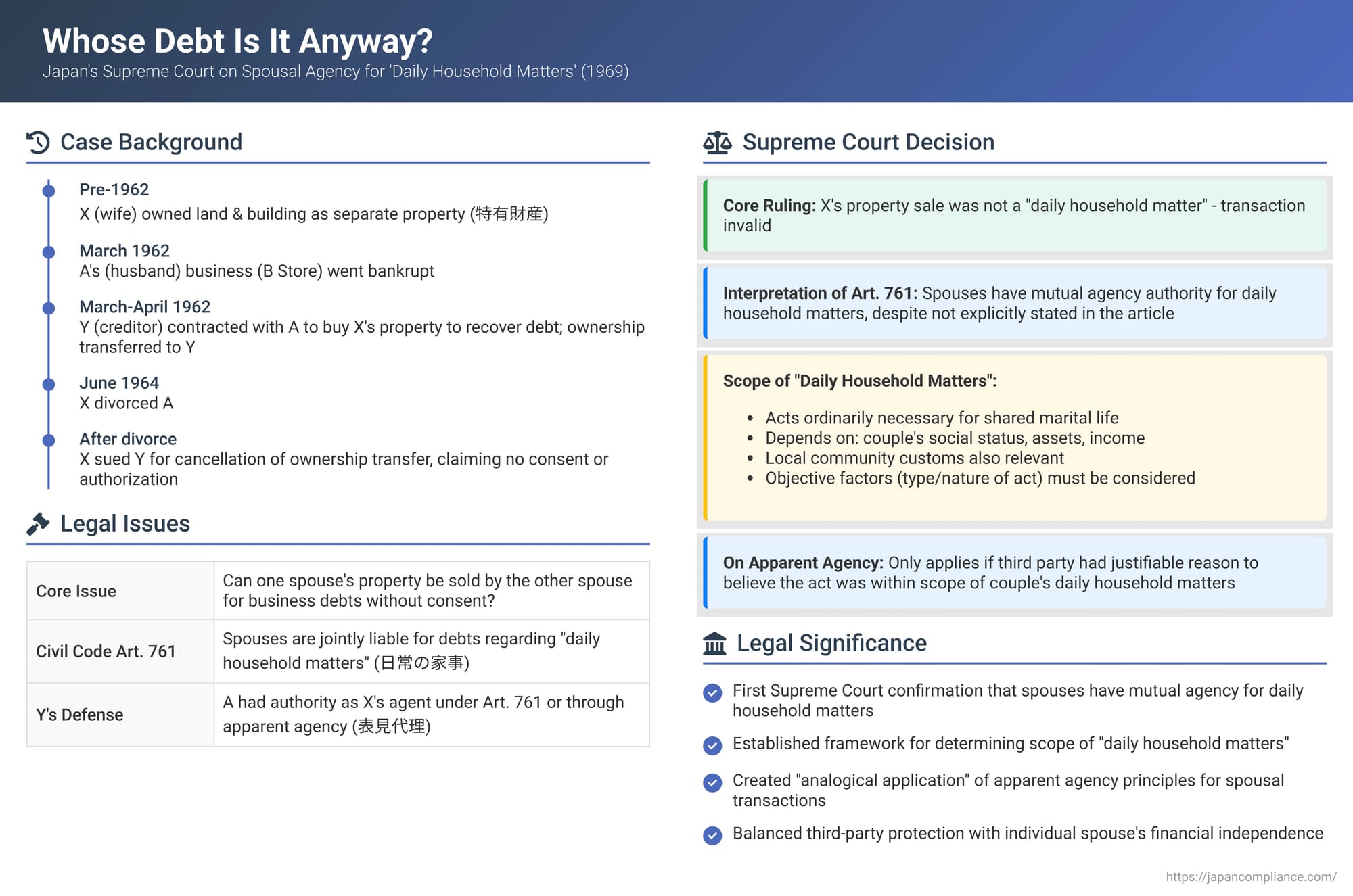

Whose Debt Is It Anyway? Japan's Supreme Court on Spousal Agency for 'Daily Household Matters'

Date of Judgment: December 18, 1969

Under Japanese Civil Code Article 761, spouses are jointly and severally liable for debts incurred by one spouse "concerning daily household matters" (日常の家事 - nichijō no kaji). This provision reflects the cooperative nature of marriage and aims to protect third parties who transact with a spouse for everyday family needs. But this seemingly straightforward rule raises several complex legal questions: Does this article implicitly grant spouses the authority to act as each other's legal agents for such household matters? What precisely falls within the amorphous scope of "daily household matters"? And, critically, what happens if one spouse engages in a significant transaction, like selling valuable family property, claiming it's for household purposes, but without the other's direct consent? Can the non-consenting spouse be bound by such an act, perhaps under the doctrine of apparent agency? The Supreme Court of Japan provided foundational answers to these questions in a landmark decision on December 18, 1969 (Showa 43 (O) No. 971).

The Facts: A Wife's Property, A Husband's Business Debt, and a Disputed Sale

The case revolved around a piece of land and a building owned by X, the wife. This property was her separate property (特有財産 - tokuyū zaisan), meaning she had owned it before her marriage to A, and it was officially registered in her name. In March 1962, A's business, known as B Store, unfortunately went bankrupt.

Y, the owner of C Company, was a creditor of A's struggling B Store. In an attempt to recover the outstanding debt, Y entered into a sales contract directly with A for the purchase of X's land and building. Shortly thereafter, in April 1962, the ownership of the property was formally transferred to Y, with the property registration documents citing a sale between X (the actual owner) and Y as the reason for the transfer. X later divorced A in June 1964.

X subsequently filed a lawsuit against Y, seeking the cancellation of the ownership transfer registration. She asserted that she had never agreed to sell her property, nor had she authorized A or anyone else to conduct the sale or the registration procedures on her behalf, thus rendering the entire transaction void.

Y's defense was twofold. Primarily, he argued that X had, in fact, granted her husband A actual agency authority to conduct the sale. Alternatively, Y contended that even if A lacked specific authority, because A was X's husband, he possessed a general agency authority under Civil Code Article 761 to represent X in matters concerning daily household affairs. Y argued that this underlying spousal agency could form the basis for applying the doctrine of apparent agency, which can sometimes bind a principal for an agent's unauthorized acts if the principal's conduct led a third party to reasonably believe the agent had authority.

The lower courts (both the Tokyo District Court and the Tokyo High Court) sided with X, the wife. They found no evidence that X had given A any specific agency authority to sell her separate property. Furthermore, they held that apparent agency based on the daily household agency of Article 761 could only apply if the third party (Y) had a justifiable reason to believe that the specific act in question (the sale of X's real estate to cover A's business debts) fell within the legitimate scope of "daily household matters." The courts found no such justifiable reason in this case. Y then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Interpretations

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, upholding the lower courts' decisions in favor of X. In doing so, it laid down several crucial interpretations of Civil Code Article 761 and its interaction with the principles of agency:

1. Spouses as Mutual Agents for Daily Household Matters (Interpreting CC Art. 761)

The Court first addressed the fundamental nature of Article 761. It ruled: "Although Article 761 of the Civil Code, in its express terms, merely provides for the effects of legal acts performed by one spouse concerning daily household matters, particularly regarding liability, it is appropriate to construe that, in substance, the said article further provides, as a prerequisite for such effects, that spouses mutually possess the authority to represent the other concerning legal acts of daily household matters."

This was a significant pronouncement. The post-war revision of the Civil Code, aimed at ensuring gender equality, had removed earlier language that explicitly "deemed" the wife to be the husband's agent for household matters. This led to a legal debate about whether the new Article 761 merely established joint liability or also implied mutual agency. While lower courts and dominant academic theories had increasingly leaned towards recognizing mutual agency, this 1969 decision was the Supreme Court's first definitive confirmation of this principle.

2. Defining the Scope of "Daily Household Matters"

Having established that spouses possess mutual agency for daily household matters, the Court then provided guidance on determining the scope of such matters: "Legal acts concerning daily household matters as referred to in Article 761 of the Civil Code mean legal acts ordinarily necessary for each married couple in the conduct of their shared life."

The Court elaborated that this scope is not fixed but is relative and depends on several considerations:

- The specific couple's internal circumstances, such as their social status, occupation, assets, and income.

- The customs of the local community where the couple resides and conducts their shared life.

- Crucially, because Article 761 also aims to protect third parties who transact with one of the spouses, the determination should not be based solely on the couple's private internal circumstances or the individual subjective purpose of the act. Instead, objective factors, such as the type and nature of the legal act itself, must also be fully considered.

Applying this framework, the Court had no difficulty concluding that A's act of selling X's separate real estate, which was her pre-marital property, in order to settle his own business debts, clearly fell outside any reasonable definition of "daily household matters" for their marriage.

3. Apparent Agency for Acts Exceeding the Scope (Interpreting CC Art. 110)

This was the most legally intricate part of the judgment. If a spouse's act exceeds the scope of their implied agency for daily household matters, can the other spouse still be bound under the general doctrine of apparent agency (Civil Code Article 110)? Apparent agency can hold a principal liable for an agent's actions if the principal created a situation where a third party reasonably believed the agent had authority, even if they didn't.

The Supreme Court ruled that a direct and general application of Article 110, using the daily household agency authority as the "basic agency power," would be inappropriate in spousal transactions. It reasoned that such a broad application "risks harming the financial independence of spouses".

Instead, the Court opted for a more restrictive approach: "unless one spouse has granted the other some other form of agency authority, it is appropriate to construe that the protection of the third party, who is the counterparty to the ultra vires act, is sufficiently achieved by analogical application of the purport of Article 110 of the Civil Code only when the third party had justifiable reason to believe that the act fell within the scope of the said couple's legal acts concerning daily household matters."

The distinction is critical:

- Under a direct application of Article 110, a third party might be protected if they reasonably believed the acting spouse had some general authority stemming from the marital relationship, even if the specific act was unusual.

- Under the Supreme Court's "analogical application" for spousal acts exceeding daily household matters, the third party is protected only if they had a "justifiable reason to believe" that the specific transaction itself was a legitimate act of daily household management for that particular couple. It's not enough to believe in a general spousal agency; the belief must pertain to the specific act's character as a household matter.

In X and A's case, the Court found it evident that Y (the creditor purchasing X's property to cover A's business debts) could not have had any justifiable reason to believe that this specific transaction—the sale of a wife's separate real estate by her husband to settle his business failures—was within the scope of their daily household affairs. Thus, Y's claim of apparent agency was rejected.

The Rationale: Balancing Third-Party Protection and Spousal Financial Independence

The Supreme Court's nuanced approach in this 1969 decision was a clear attempt to strike a delicate balance between two important legal objectives:

- Protecting Third Parties: Ensuring that individuals or businesses dealing with one spouse in matters that genuinely appear to be for the household are not unfairly left with unenforceable agreements or unpaid debts.

- Protecting Spousal Financial Independence: Safeguarding each spouse's separate property and financial autonomy from unauthorized and significant dispositions by the other spouse, especially in an era of increasing gender equality and recognition of individual property rights within marriage.

The Court feared that if the general agency for daily household matters could too easily serve as the foundation for apparent agency for any act, one spouse might be able to encumber or dispose of the other's significant assets without their consent, undercutting their financial independence. The "analogical application" with its stricter belief requirement was designed to prevent this.

Ongoing Debate and Critique

The Supreme Court's solution, while influential, has been the subject of considerable academic discussion and critique:

- Clarity of the Standard: Some scholars question whether the distinction between the "justifiable reason" required under the Court's analogical approach and the standard "justifiable reason" under a direct application of Article 110 is practically significant or easy to apply, especially given that the concept of "daily household matters" is itself inherently flexible and fact-dependent.

- Redundancy or "Double Protection"? Since the Court's definition of "daily household matters" (in Point II of its reasoning) already incorporates considerations of third-party protection by looking at objective factors like the type and nature of the act, some argue that invoking apparent agency principles for acts already deemed objectively outside that scope might be redundant or offer an unwarranted "double layer" of protection analysis.

- Alternative Approaches: Some critics suggest that the legal framework might be simpler and more coherent if issues of unauthorized spousal acts were primarily dealt with through general agency principles (i.e., did the non-acting spouse actually grant specific authority, or did their conduct create a clear appearance of such authority for that specific transaction?). Under this view, Article 761 would primarily define the scope of automatic joint liability for true household debts, without necessarily being the basis for complex apparent agency arguments for acts clearly beyond that scope. The focus, for acts outside daily household matters, would shift more directly to proving actual or specifically apparent agency for the transaction in question.

Conclusion: A Foundational Judgment on Marital Agency and Property

The Supreme Court's December 1969 decision remains a cornerstone of Japanese family law. It definitively established that spouses possess mutual agency for daily household matters, providing crucial guidance on a point previously subject to debate. It also offered a framework—albeit a complex one—for determining the scope of these everyday matters, blending subjective couple-specific factors with objective transactional characteristics.

Perhaps most significantly, the ruling carefully delineated how the doctrine of apparent agency applies when a spouse acts beyond this implied authority for household affairs. By opting for an "analogical application of the purport of Article 110" with a specific belief requirement, the Court sought to protect the financial independence of the non-acting spouse while still providing a pathway—though a narrowed one—for third parties to seek redress if they reasonably believed a particular act was within the legitimate domain of the couple's shared household management. In the specific circumstances of this case, the Court made it clear that the disposition of a spouse's major separate property asset to settle the other spouse's unrelated business debts falls far outside the realm of "daily household matters," and a creditor involved in such a transaction would find little shelter under the principles of apparent agency based on marital status alone. The judgment continues to inform legal understanding of the delicate balance between marital cooperation, individual property rights, and third-party expectations in spousal dealings.