Whose Car Is It Anyway? A Japanese Supreme Court Case on Stolen Vehicles, International Sales, and Choice of Law

Date of Judgment: October 29, 2002

Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

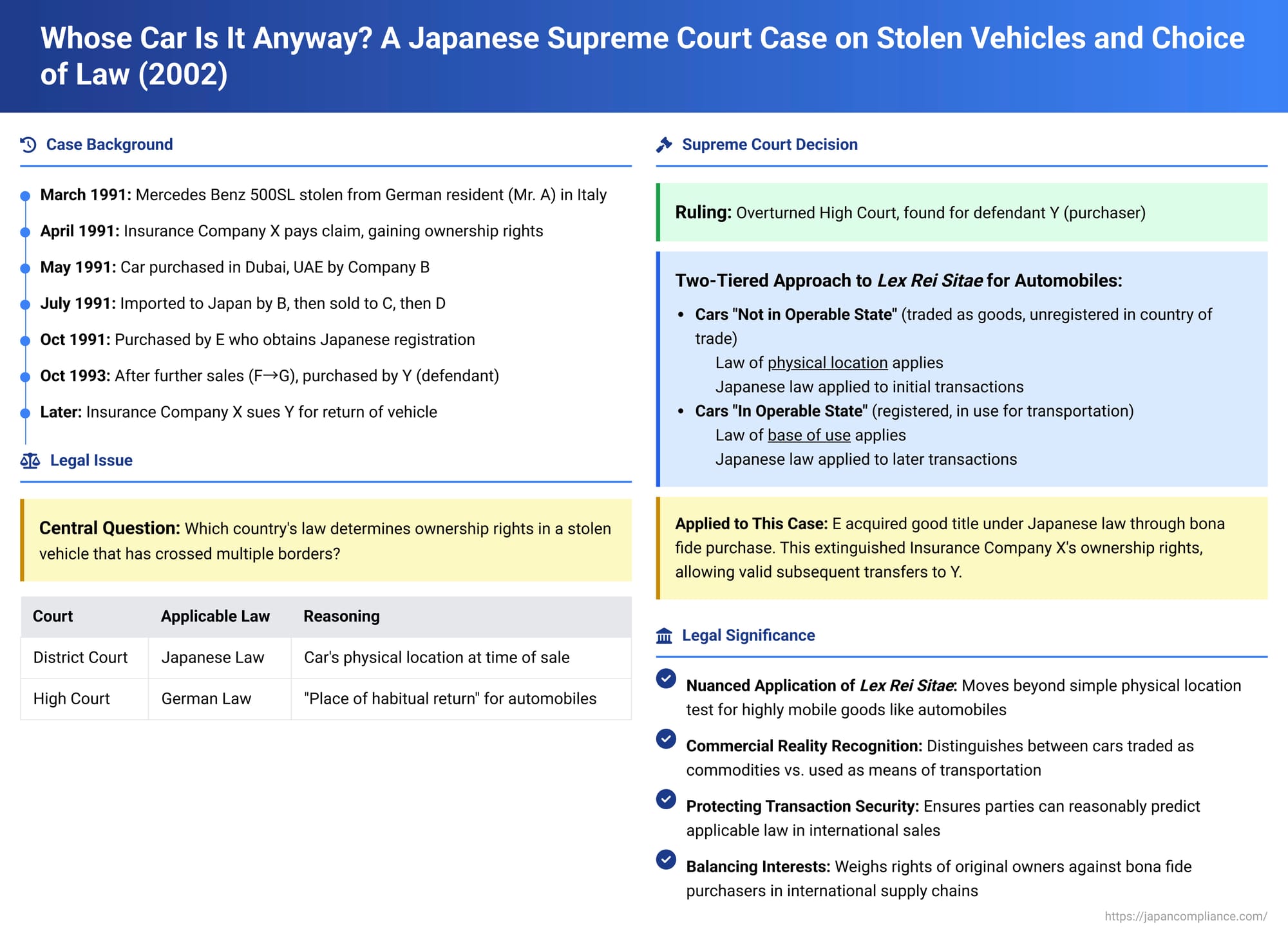

The principle of lex rei sitae (law of the situs) is a cornerstone of private international law, dictating that the law of the place where property is located governs rights in that property. While straightforward for immovable property, its application to movable goods, especially those like automobiles that routinely cross international borders, can present significant complexities. A Japanese Supreme Court decision from October 29, 2002, grappled with such a scenario involving a stolen German car that was subsequently imported into Japan and sold multiple times, ultimately clarifying how Japanese courts determine the applicable "situs law" for automobiles in international transactions.

The Journey of a Stolen Car: From Germany to Japan via the UAE

The case traced the convoluted path of a Mercedes Benz 500SL:

- The car was initially registered in Germany and used by its German resident owner, Mr. A. Mr. A had a lease agreement for the car and an insurance policy with X Insurance Company (the plaintiff).

- In March 1991, the car was stolen from Mr. A while he was in Italy.

- X Insurance Company paid the insurance claim to Mr. A and the lease company. The insurance policy stipulated that X Insurance would acquire ownership of the car if it was not recovered within one month of the insurance payout.

- Around May 1991, an entity named B (K.K. Inter-Auto in the judgment details) purchased the car in Dubai, UAE, from a used car dealer. B then imported the car into Japan in July 1991, obtaining an automobile customs clearance certificate.

- The car then went through a series of transactions in Japan: from B to C (Y.K. Nikata Motors), then to D (K.K. Kosei Kogyosho).

- Subsequently, Mr. E (using the initial B from the judgment's anonymized party list, but referred to as E here for clarity in the chain) purchased the car from D and, in October 1991, obtained a new registration for it under Japanese law.

- After E's registration, the car was sold to F (K.K. Yanase) and then to G (Autopia Nakajima K.K.).

- Finally, in October 1993, Mr. Y (the defendant) acquired the car. Both G and Y duly completed transfer registrations in Japan.

- A crucial fact was that none of the parties who purchased the car within Japan had been shown vehicle certificates or similar documents that could confirm the exporter's (B's) ownership title.

- X Insurance Company, claiming ownership through the insurance payout, sued Mr. Y for the return of the vehicle.

The Lower Courts' Diverging Paths

The lower courts took different approaches to determining the applicable law:

- The Urawa District Court (Koshigaya Branch), as the court of first instance, applied Japanese law. It reasoned that the car was physically located in Japan, invoking the standard lex rei sitae rule (Article 10 of the old Horei, Japan's then-prevailing Act on Application of Laws, principles now in Article 13 of the current Act on General Rules for Application of Laws). Based on Japanese law, the court dismissed X Insurance Company's claim.

- The Tokyo High Court, on appeal, reversed this decision. It opined that for highly mobile goods like automobiles, the "situs" for choice-of-law purposes should generally be understood not as its transient physical location but as its "place of habitual return" or "registration place." Given the car's German registration and use, the High Court considered Germany to be its relevant situs. Applying German law (under which, the High Court found, bona fide acquisition of stolen vehicles was difficult, especially without checking vehicle documents), it ordered the car to be returned to X Insurance Company. Mr. Y then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Two-Tiered Approach to "Situs" for Automobiles

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision, ultimately ruling in favor of Mr. Y. The Court's reasoning established a nuanced framework for applying the lex rei sitae principle to automobiles, distinguishing between their state of use:

1. General Principle for Tangible Property:

The Court began by affirming that Article 10(2) of the Horei (governing the acquisition or loss of rights in movable and immovable property by the law of the situs where the causal facts are completed) generally refers to the law of the property's physical location. This is because rights of exclusive control (like ownership) are intimately linked with the interests of the country where the property is physically situated.

2. The Dichotomy for Automobiles:

The Supreme Court recognized the unique nature of automobiles: they are designed for mobility and often cross borders, and many jurisdictions require registration for them to be legally operable. Cars can be traded internationally either unregistered (as new vehicles) or with their prior registration cancelled (as used vehicles) – in either case, they might not be immediately ready for road use. This led the Court to identify two distinct states for automobiles relevant to choice of law:

- Cars "Not in an Operable State" (運行の用に供し得ない状態 - unkō no yō ni kyōshi enai jōtai):

This category includes cars traded as goods, such as new unregistered cars or used cars whose previous registration has been cancelled, or cars that are otherwise not in a condition to be legally driven. For these vehicles, the Court held that:- They lack a "base of use" (riyō no honkyochi).

- The acquisition or loss of rights in them is closely connected to the interests of the country of their physical location at the time the transaction (the "causal facts" for ownership transfer) is completed.

- Determining their physical location at that specific time is generally not difficult.

- Applying a law other than that of the physical situs (e.g., a distant registration law) to such cars, especially those imported as "unregistered" for trade (even if technically still registered elsewhere, as in this case), would create uncertainty for parties involved in the transaction. They might not easily know which country's law would govern their rights.

- Such uncertainty would undermine transactional security from a private international law perspective, as parties should be able to reasonably predict the applicable law.

- Therefore, for cars in this non-operable state, the governing law for acquisition/loss of ownership is the law of their physical location when the causal facts are completed, unless there are special circumstances (like the car merely being in transit to a known destination country, making the current physical situs fortuitous and problematic).

- Cars "In an Operable State" (運行の用に供し得る状態 - unkō no yō ni kyōshi uru jōtai):

This category covers cars that are registered and in general use for transportation, capable of extensive movement across borders. For these vehicles, the Court reasoned:- If the law of the constantly changing physical location were applied, the governing law would become unstable and difficult to ascertain at any given moment.

- The connection between the car's legal rights and the interests of a merely transient physical location becomes tenuous.

- In such cases, it is more appropriate to apply the law of the car's "base of use" (riyō no honkyochi) as the situs law.

- When such an operable car is traded, the buyer can typically obtain information regarding its registration and management, making the law of its base of use more transparent and conducive to transactional security for the buyer than the law of a potentially accidental physical location.

The Supreme Court's formal statement of the rule (Point 4(1)ウ of the judgment):

"Based on the above, the 'situs law' referred to in Article 10(2) of the Horei, which is the standard for determining the governing law for the acquisition of ownership of an automobile, should be interpreted as follows: if, at the time the facts constituting the cause for the acquisition or loss of rights were completed, the automobile was in a state where it could be put to operational use, it is the law of its base of use. If it was not in a state where it could be put to operational use, it is the law of its physical location, unless there are circumstances such as the automobile being in transit to another country."

Applying the Framework to the Stolen Mercedes Benz:

The Supreme Court then meticulously applied this two-tiered framework to the chain of transactions:

- Transactions Involving B, C, D, and E:

The Court determined that "the completion of facts constituting the cause for acquisition of ownership by bona fide acquisition (sokuji shutoku)" is the point at which the buyer obtains possession of the car.

At the time B, C, D, and E each acquired possession, the Mercedes Benz, although still formally registered in Germany, was found to be not in an operable state in Japan. It had been imported as a commodity for sale.

Therefore, the governing law for determining whether these parties acquired ownership was the law of the car's physical location at each respective time of possession transfer, which was Japan. - E's Bona Fide Acquisition under Japanese Law:

The Supreme Court then assessed whether E acquired ownership under Japanese law (specifically, Article 192 of the Civil Code on bona fide acquisition of movables). It found that E did acquire good title. The Court criticized the High Court's stringent requirements for buyers of imported unregistered cars to verify foreign ownership documents, stating that there was no evidence that such rigorous checks were standard practice in Japanese imported car transactions, nor were such extensive foreign documents required for new vehicle registration in Japan. Since E purchased the car from D (K.K. Kosei Kogyosho), a dealer against whom no suspicion of dealing in stolen goods was apparent from the record, and all documents necessary for Japanese registration were provided, E was deemed to have acquired the car without negligence. As X Insurance Company did not prove facts to overturn the presumption of E's good faith and lack of negligence, E validly acquired ownership. At this point, X Insurance Company lost its ownership title. - Transactions Involving F, G, and Y:

By the time F, G, and Y acquired possession of the car, E had already completed the new registration process in Japan, rendering the car operable. Japan had clearly become its "base of use".

Therefore, Japanese law also governed these subsequent transfers. Since E had obtained good title under Japanese law, F, G, and ultimately Y validly acquired ownership through this chain of succession.

Outcome and Key Takeaways

The Supreme Court concluded that X Insurance Company's claim was unfounded because its ownership had been extinguished when E acquired the car through bona fide purchase under Japanese law. Mr. Y, as the final purchaser in a chain stemming from E's valid title, was recognized as the rightful owner.

Insights from the accompanying commentary by Professor Kanzen highlight:

- The Supreme Court's decision offers a nuanced interpretation of lex rei sitae for automobiles, moving beyond a simple physical location test and incorporating the "base of use" concept, depending on the car's operational state and how it's being traded.

- Registration status is a significant factor in determining "operability," but the Court also considered the context of the transaction (e.g., being traded as if unregistered).

- The precise definitions of "base of use" and the exact criteria for "operability" remain somewhat open to further clarification in future cases.

- The judgment implicitly acknowledges a potential exception for goods that are merely in transit through a country, where applying the law of that transient physical location might be inappropriate.

Conclusion: Adapting Legal Principles to Commercial Realities

This Supreme Court ruling is pivotal for its adaptation of traditional conflict of laws principles to the modern realities of international commerce involving highly mobile and often valuable goods like automobiles. By distinguishing between cars traded as commodities (non-operable state) and cars used as means of transport (operable state), the Court sought to provide a framework that enhances legal certainty, protects the security of transactions, and appropriately balances the interests of original owners with those of subsequent bona fide purchasers in complex international supply chains. The decision underscores the importance of the factual context of transactions in determining the applicable law for resolving ownership disputes over property that has crossed multiple borders.