Who's the Real Shareholder? Japan's Supreme Court on Nominee Share Subscriptions

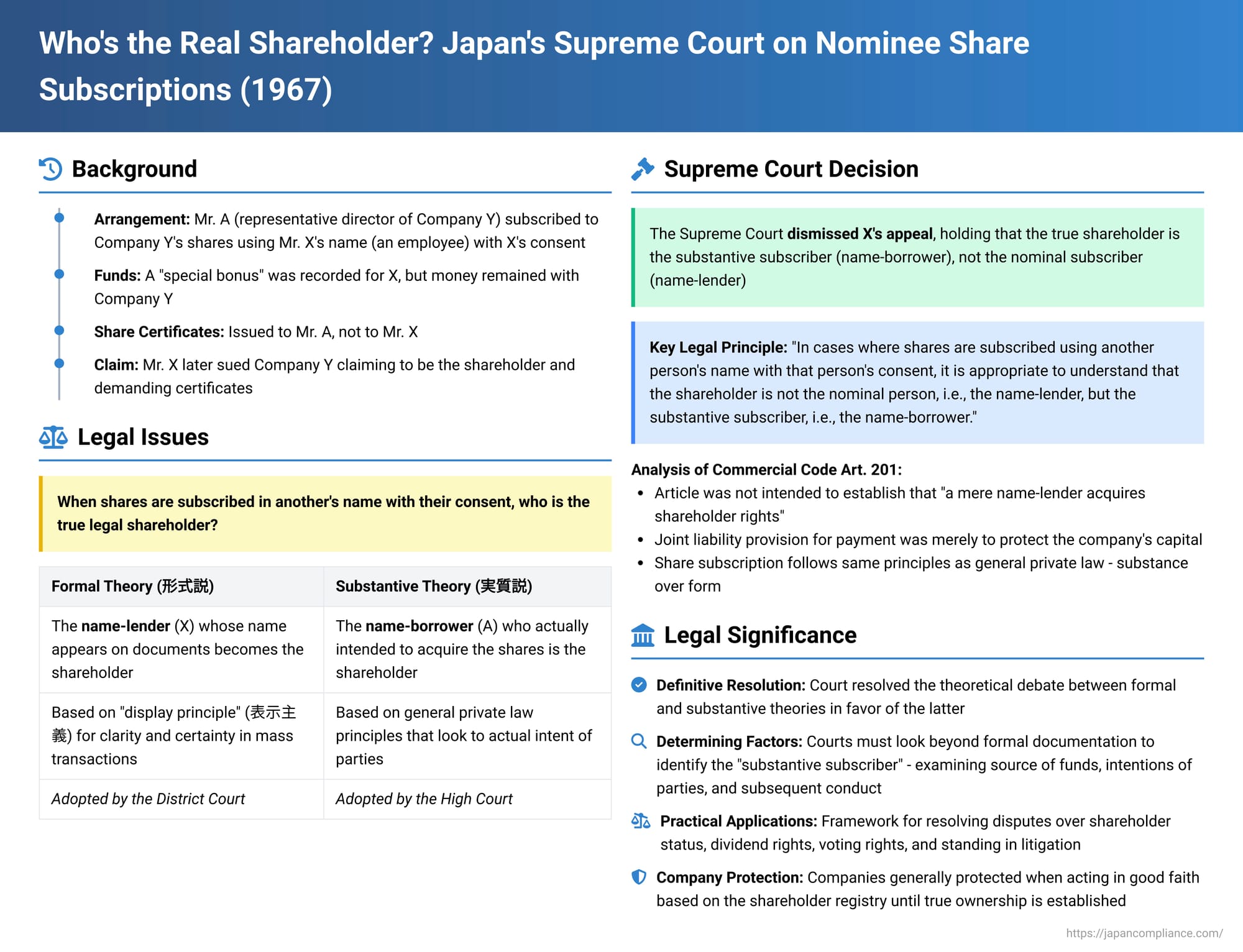

In the world of corporate shareholdings, it's not uncommon for shares to be registered in the name of one person while actually being owned or controlled by another. Such "nominee shareholdings" can serve various legitimate purposes, but they also raise a fundamental legal question: when a share subscription is made using another person's name with their consent, who is the true legal shareholder? Is it the person whose name appears on the application (the nominee or "name-lender"), or the person who actually intended to acquire the shares and effectively arranged for the subscription (the "name-borrower" or beneficial owner)? A Japanese Supreme Court decision on November 17, 1967, provided a definitive answer to this question, favoring substance over form.

The Facts: A Bonus, Shares, and a Dispute Over Ownership

The case involved Mr. X, an employee of Company Y, and Mr. A, the representative director of Company Y. Mr. A, with Mr. X's consent, used Mr. X's name to subscribe to newly issued shares in Company Y. The arrangement was structured to appear as though Mr. X received a special bonus from the company, and this "bonus" money was then purportedly used to pay for the shares issued in Mr. X's name. In reality, the funds corresponding to this supposed bonus were never actually paid out to Mr. X but were retained by Company Y. Subsequently, the share certificates for these shares (referred to as "the shares in question") were issued not to Mr. X, but to Mr. A.

Mr. X later filed a lawsuit against Company Y. Initially, his claim was for the issuance of the share certificates to him.

Lower Courts' Diverging Paths to the Same Outcome

The case took an interesting path through the lower courts, with both ultimately denying Mr. X's claim but for different underlying reasons regarding shareholder identity:

- Tokyo District Court (First Instance): The District Court dismissed Mr. X's claim. Its reasoning was based on what is often termed the "formal theory." It held that when shares are subscribed in a nominee's name with that nominee's consent, the nominee (the name-lender, Mr. X in this case) becomes the legal shareholder in relation to the company, regardless of any internal understanding or arrangement between the name-lender and the name-borrower (Mr. A). However, despite finding Mr. X to be the formal shareholder, the court still dismissed his claim because it found that there had been an explicit or implicit agreement between Mr. X and Mr. A whereby Mr. X had effectively granted all rights associated with the shares registered in his name to Mr. A.

- Tokyo High Court (Second Instance): Mr. X appealed this decision. In the appellate proceedings, he amended his claim to seek a formal declaration that he was the shareholder and an order for Company Y to deliver the share certificates to him. The Tokyo High Court also dismissed Mr. X's appeal, but it did so based on a different legal interpretation, one often referred to as the "substantive theory." The High Court explicitly stated that "it is appropriate to understand that the substantive subscriber, i.e., the name-borrower (Mr. A), becomes the shareholder, not the name-lender (Mr. X)." Since it found Mr. X was merely a name-lender and Mr. A was the substantive party, Mr. X's claim to shareholder status failed.

Mr. X then appealed to the Supreme Court. His argument before the highest court emphasized the collective and mass-transaction nature of share subscription contracts. He contended that, unlike ordinary private law transactions where courts seek to identify the "true party" to determine legal effects, shareholder status in this context should be determined formally and uniformly, based on the externally recognizable name appearing on the subscription documents. This was an argument in favor of the formal theory.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Ruling: Substance Over Form

The Supreme Court, in its Second Petty Bench judgment, dismissed Mr. X's appeal, thereby affirming the High Court's outcome but, more importantly, endorsing its reasoning based on the "substantive theory."

- Adoption of the "Substantive Theory": The Court unequivocally stated: "In cases where shares are subscribed using another person's name with that person's consent, it is appropriate to understand that the shareholder is not the nominal person, i.e., the name-lender, but the substantive subscriber, i.e., the name-borrower."

- Interpretation of (then) Commercial Code Article 201: A significant part of the Court's reasoning involved its interpretation of Article 201 of the Commercial Code then in effect. This article addressed liability for share subscriptions made in a fictitious name or in another's name without consent (Paragraph 1), and also stipulated joint and several liability for payment between a name-lender and a name-borrower when the name was used with consent (Paragraph 2). The Supreme Court interpreted this article as follows:

- Paragraph 1, regarding fictitious names or unauthorized use of another's name, merely codified the "obvious principle that the substantive subscriber bears the obligations of a share subscriber, regardless of the name used."

- Paragraph 2, imposing joint liability for payment on the name-lender and name-borrower in cases of consensual nominee subscription, was specifically aimed at ensuring the payment obligation to the company was met.

- Crucially, the Court concluded that Article 201 was not intended to establish a rule that a "mere name-lender acquires shareholder rights."

- Alignment with General Principles of Private Law: Based on this interpretation, the Supreme Court held that the determination of who is the subscriber (and thus who acquires shareholder rights and obligations) in the context of share subscriptions should follow the same principles as in general private law transactions. That is, "the person who genuinely made the application as a contracting party acquires the rights and assumes the obligations of a subscriber."

Since the High Court had found that Mr. X was merely a name-lender and that Mr. A was the substantive party behind the subscription, and because the Supreme Court endorsed this substantive approach, Mr. X's appeal (which argued for a formal determination of his shareholder status) was dismissed.

The "Substantive Theory" vs. "Formal Theory"

This Supreme Court judgment was pivotal because it clearly sided with the "substantive theory" (jisshitsu-setsu) over the "formal theory" (keishiki-setsu) in cases of consensual nominee share subscriptions.

- The Substantive Theory: This theory posits that the person who genuinely intends to subscribe to the shares and who effectively undertakes the subscription (typically the name-borrower, who often provides or arranges for the funds) is the true shareholder, regardless of the name formally used on the subscription documents. This view is supported by many legal scholars in Japan. Arguments in its favor include:

- Consistency with how cases involving fictitious names or unauthorized use of another's name are treated (where the actual party is held responsible).

- Alignment with the general principles of contract law, which seek to identify the true intent and identity of the contracting parties.

- The need to achieve substantively just outcomes and prevent the nominee arrangement from being used to obscure the true ownership or control.

- The Formal Theory: This theory argues that the person whose name is formally used on the subscription documents (the name-lender or nominee) should be recognized as the legal shareholder vis-à-vis the company. This view was adopted by the first instance court in this case and had support among some earlier scholars. Arguments for the formal theory included:

- The collective and mass nature of share dealings, which arguably requires a clear, formal, and easily ascertainable basis (the registered name) for determining shareholder status to ensure efficiency and predictability ("display principle" or hyōji-shugi).

- The specific wording of the then-Commercial Code Article 201, Paragraph 2, which imposed joint payment liability on both the name-lender and name-borrower, was sometimes interpreted as implying that the name-lender held some form of primary status.

- Perceived legislative intent behind the original enactment of Article 201.

The Supreme Court's 1967 decision significantly strengthened the substantive theory's position. Some of the traditional arguments for the formal theory have weakened over time, especially since Article 201 of the old Commercial Code (a key interpretative battleground) was not carried over into the current Companies Act (enacted in 2005). The requirement for formality in share applications has also been somewhat relaxed under the Companies Act (e.g., signatures are not explicitly required on application forms, though written applications are), diminishing the argument for a strictly formalistic interpretation based on the application document itself.

Identifying the "Substantive Subscriber"

While the substantive theory provides a general principle, its application requires a factual determination of who the "substantive subscriber" actually is in any given case. This judgment emphasizes looking at who "genuinely made the application as a contracting party."

- Source of Funds: A primary factor often considered is who actually provided the economic contribution or funds for the share payment.

- Intent of the Parties: Ultimately, the inquiry centers on the true intentions of the involved parties (name-lender, name-borrower, and sometimes the company itself).

- Complexity in Practice: Determining this can be complex. In the present case, the funds for the shares notionally came from a "special bonus" to Mr. X, but these funds were retained by the company, and the share certificates went to Mr. A.

- Other Evidentiary Factors: Courts may look at a range of circumstantial evidence, including who received dividends, who exercised voting rights, who received shareholder notices, and the overall relationship and understanding between the nominee and the alleged beneficial owner. Subsequent conduct can serve as indirect evidence of the original intent.

Implications and Related Issues

The Supreme Court's adoption of the substantive theory has several implications:

- Dispute Resolution: It provides a framework for resolving various disputes arising from nominee shareholdings, such as claims for share certificates (as in this case), challenges to the validity of shareholder meeting resolutions (if votes were cast by a mere nominee not acting for the beneficial owner), and questions of standing in shareholder litigation.

- Company's Position: While the substantive owner is recognized as the shareholder, a company is generally protected if it acts in good faith and treats the person registered in the shareholder registry (who might be the nominee) as the shareholder for purposes like sending notices or paying dividends, at least until the true ownership is established and reflected in the registry. The Companies Act includes provisions that notices sent by the company to the address provided by the share applicant are deemed effective, which supports this principle of protecting the company's administrative processes.

- Registration and Assertion of Rights: Differing views on whether a substantive shareholder who is not on the share register must first seek rectification of the register before asserting rights against the company. Some case law suggests substantive proof of shareholding is enough for original subscribers, while other views require formal registration or a claim for it.

- Potential Liability of the Name-Lender: Even if the name-borrower is deemed the true shareholder, the name-lender (nominee) might still face certain liabilities, for instance, for the payment of share capital to the company, potentially based on an analogy to principles of apparent authority or specific statutory provisions governing liability for lending one's name (e.g., Article 9 of the Companies Act, concerning liability of a person who allows their name to be used in a business).

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's November 17, 1967, judgment represents a significant clarification in Japanese company law regarding nominee share subscriptions. By decisively endorsing the "substantive theory," the Court established that the law will look beyond the formal name used in a share subscription to identify the true, substantive party who intended to acquire the shares and for whose benefit the transaction was made. This approach, grounded in general principles of private law that seek to give effect to the genuine intentions of contracting parties, prioritizes substance over mere form. While determining the "substantive subscriber" can involve complex factual inquiries, this ruling affirmed a flexible and equitable approach to resolving disputes over shareholder identity in the context of consensual nominee arrangements, ensuring that the legal determination of share ownership aligns with the underlying reality of the transaction.