Who Sues for the Common Good? Japan's Supreme Court on Condominium Association Standing

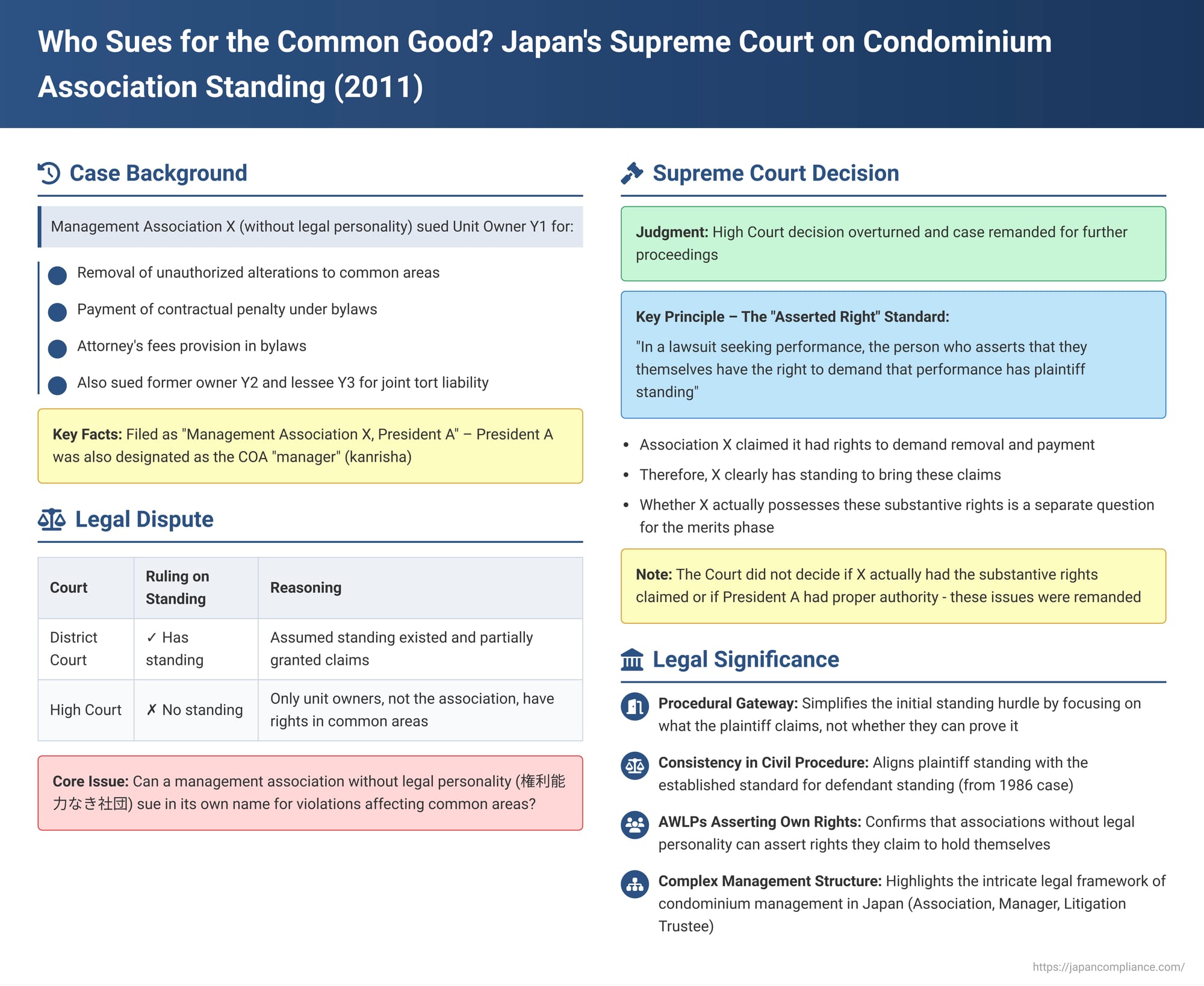

When a condominium unit owner breaches the community's rules, for instance by making unauthorized alterations to common areas, who has the legal right to step in and demand rectification or compensation? Can the condominium's management association, often an unincorporated entity, initiate a lawsuit in its own name? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this fundamental question of plaintiff standing in a judgment delivered on February 15, 2011 (Heisei 21 (Ju) No. 627), in a case involving a management association seeking various remedies against a rule-violating unit owner and related parties.

The Dispute: Unauthorized Alterations and a Management Association's Lawsuit

The plaintiff, X, was the management association of Condominium M, operating as an "association without legal personality" (kenri nōryoku naki shadan)—a common structure for such bodies in Japan. The defendants included Y1, the current owner of a first-floor unit in Condominium M; Y2, the former owner of that unit; and Y3, a lessee of the unit.

Management Association X alleged that Defendant Y1 had violated the condominium's management bylaws (honken kiyaku) by making illegal modifications and constructions in the common areas of the building. Based on provisions in the Condominium Ownership Act (COA) and its own bylaws (specifically citing COA Articles 6 and 57, and Bylaw Article 66, Paragraph 1 concerning measures against rule violators), Association X brought several claims, primarily against Y1:

- The removal of the illegally constructed installations (as per Bylaw Article 66, Paragraph 2). Alternatively, X sought payment of an alteration approval fee (Bylaw Article 14, Paragraph 3) and a usage fee for the altered first-floor entrance area (Bylaw Article 14, Paragraph 4).

- Payment of a contractual penalty (Bylaw Article 66, Paragraph 2).

- Payment of attorney's fees (Bylaw Article 67, Paragraph 4).

- Additionally, X sought damages from Y1 equivalent to usage fees for signage and other items that allegedly remained in common areas without authorization after a usage agreement had terminated.

X also pursued claims against Y2 (former owner) and Y3 (lessee) for joint tort liability concerning amounts equivalent to the penalty and attorney's fees sought from Y1.

The High Court's Hurdle: Association Lacks Standing

The first instance court (Tokyo District Court) had assumed Management Association X possessed the standing to sue (genkoku tekikaku) and partially granted some of its claims against Y1. X appealed parts of this decision.

However, the Tokyo High Court took a different view and dismissed X's entire lawsuit, ruling that the association itself lacked standing. The High Court reasoned that since the common areas of a condominium are co-owned by all the unit owners, any legal claims concerning these areas should properly be brought by the unit owners themselves. It stated that no specific legal provision grants a management association (as an association without legal personality) the authority to conduct such litigation on behalf of the unit owners. Furthermore, it opined that since the COA allows for a "manager" (kanrisha) to be authorized to sue, there was no compelling practical need to also recognize such standing for the association itsel.

Management Association X appealed this dismissal to the Supreme Court. X argued, among other things, that the lawsuit was effectively being pursued by its president, A, in his capacity as the COA-defined "manager," duly authorized by an association resolution to act as a litigation trustee for claims against rule violators (an "optional litigation trust" - nin'iteki soshō tantō under COA Art. 26(4) and Art. 57). The lawsuit documents had identified the plaintiff as "Management Association X, President A".

The Supreme Court's Clarification (February 15, 2011): The "Asserted Right" Standard

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's judgment and remanded the case for further proceedings.

The Court laid down a clear, general principle for determining plaintiff standing in lawsuits seeking specific performance or payment (known as kyūfu no uttae, or "claims for a giving"):

- Core Principle for Plaintiff Standing: "In a lawsuit seeking performance, the person who asserts that they themselves have the right to demand that performance has plaintiff standing".

- Application to the Case: "Each of the present claims is one in which Management Association X asserts that X itself has the right to demand the removal of the installations or the payment of monies related to these claims from Y and others, and seeks that performance. It is clear that Management Association X has plaintiff standing for the lawsuits related to these claims".

What This Means (and Doesn't Mean)

- Procedural Green Light: The Supreme Court's ruling provides a procedural green light. If an entity comes to court asserting that it has a particular right and seeks enforcement of that right, it meets the threshold requirement of standing to sue. This simplifies the initial procedural hurdle.

- Substantive Questions Remain for Remand: Crucially, the Supreme Court did not decide whether Management Association X actually possessed the substantive rights it claimed (e.g., the right to demand removal, collect penalties, or receive damages in its own name). Nor did it rule on whether its representative, President A, had the proper authority under the COA or the bylaws to pursue each specific claim, either on behalf of the association or in his capacity as the "manager." These substantive issues, including the proper identification of the plaintiff party (Association X itself, or President A as manager/litigation trustee), were sent back to the High Court for full deliberation.

The Underlying Complexity: Who Represents the Collective in Condominium Law?

The question of who can sue in condominium-related disputes is often complex due to the unique legal structure of condominium ownership and management in Japan.

- The "Association Without Legal Personality" (AWLP): Most Japanese condominium management associations are AWLPs (kenri nōryoku naki shadan). These are groups with organizational structures (bylaws, majority decision-making, representative organs, continuous identity) but without formal incorporation as legal persons. Article 29 of the Code of Civil Procedure grants such associations, if they have a designated representative, the capacity to be a party in litigation (i.e., they can sue and be sued in their own name). However, this provision primarily grants party capacity (the ability to appear in court) and does not automatically mean the AWLP is the substantive holder of all rights or property related to the condominium. Legal scholars have debated whether Article 29 essentially confers a form of statutory litigation trust upon AWLPs, allowing them to act for the collective in certain matters.

- The COA "Manager" (kanrisha): The Condominium Ownership Act allows for the appointment of a "manager" (COA Article 25, Paragraph 1). This manager can be authorized by the condominium's bylaws or by resolutions of the unit owners' assembly to perform various management duties, including acting as an agent for the unit owners in certain financial claims (COA Article 26, Paragraph 2) and, significantly, to sue or be sued on behalf of the collective (COA Article 26, Paragraph 4). It's common practice in Japan, often reflected in standard condominium bylaws (like the government's model "Standard Management Bylaws"), for the association's president (rijichō) to also serve as this COA-defined "manager". This was the situation for Association X and its President A.

- Litigation Trustee for Rule Violations: For specific types of actions against unit owners who violate their obligations (e.g., actions to stop infringing behavior, demand the sale of a unit, or, in the case of a lessee, terminate their lease and demand surrender, as per COA Articles 57-60), the COA requires that the manager or a specifically designated unit owner be appointed as a "litigation trustee" by a formal resolution of the unit owners' assembly (COA Article 57, Paragraphs 2 and 3).

- The Confusion in This Case: The lawsuit was filed under the name "Management Association X, President A". The plaintiff's side argued that President A was acting in his capacity as the authorized "manager" and as a litigation trustee based on an assembly resolution. The High Court, however, appears to have interpreted the plaintiff as being Management Association X itself, in its capacity as an AWLP. The Supreme Court's remand for further deliberation suggests that this ambiguity regarding the precise identity and capacity of the plaintiff also needed to be resolved by the High Court.

Significance of the Supreme Court's Standing Rule

- Consistency in Procedural Law: The ruling aligns the standard for determining plaintiff standing in claims for performance with the pre-existing standard for defendant standing (established in a Supreme Court case from Showa 61 [1986]). This brings a welcome consistency to procedural requirements.

- Focus on Assertion of Right: By focusing on what the plaintiff claims or asserts in its pleadings, the Supreme Court's rule simplifies the initial procedural hurdle of standing. The question of whether the plaintiff can actually prove that asserted right is a matter for the substantive trial on the merits.

- AWLPs Asserting Their "Own" Rights: The decision is particularly noteworthy for confirming that an AWLP can have plaintiff standing when it asserts rights it claims to hold itself. While AWLPs are not full legal persons, they can be recognized as holding certain collective rights or assets. The judgment affirms their ability to come to court to enforce such self-asserted rights, separate from merely acting as a representative or trustee for individual unit owners (though the nature and scope of an AWLP's "own" rights can be intricate and subject to the specifics of the COA and the association's bylaws).

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2011 decision provides a clear and broad procedural rule for determining a plaintiff's standing in Japanese civil litigation: if a party asserts it holds a right and seeks the court's assistance in enforcing that right against another, it has standing to bring the lawsuit. This is a practical approach that allows claims to be heard.

However, for condominium management associations, securing this initial standing is merely the first step. The more complex challenge, as highlighted by the remand in this case, lies in proving that the association (either in its own capacity as an AWLP or through its duly authorized manager acting as a litigation trustee) actually possesses the substantive legal right to make the specific claims and that all necessary internal authorizations (like assembly resolutions) have been obtained. The case underscores the intricate legal framework governing condominium management in Japan and the ongoing need for clarity in how collective rights are asserted and disputes are resolved.