Who Pays the Bills? Promoter Liability for Company Incorporation Expenses in Early Japanese Law

The birth of a company is rarely a cost-free endeavor. Promoters, the architects of a new corporate entity, often incur various expenses during the formation process – from legal fees and registration costs to advertising for initial share subscriptions. A fundamental legal question then arises: who is ultimately responsible for these "incorporation expenses"? Do the promoters bear them personally, or does the liability transfer to the newly formed company? An early and influential decision by Japan's Great Court of Cassation (Daishin'in, the precursor to the modern Supreme Court) on July 4, 1927, provided key principles for addressing this issue.

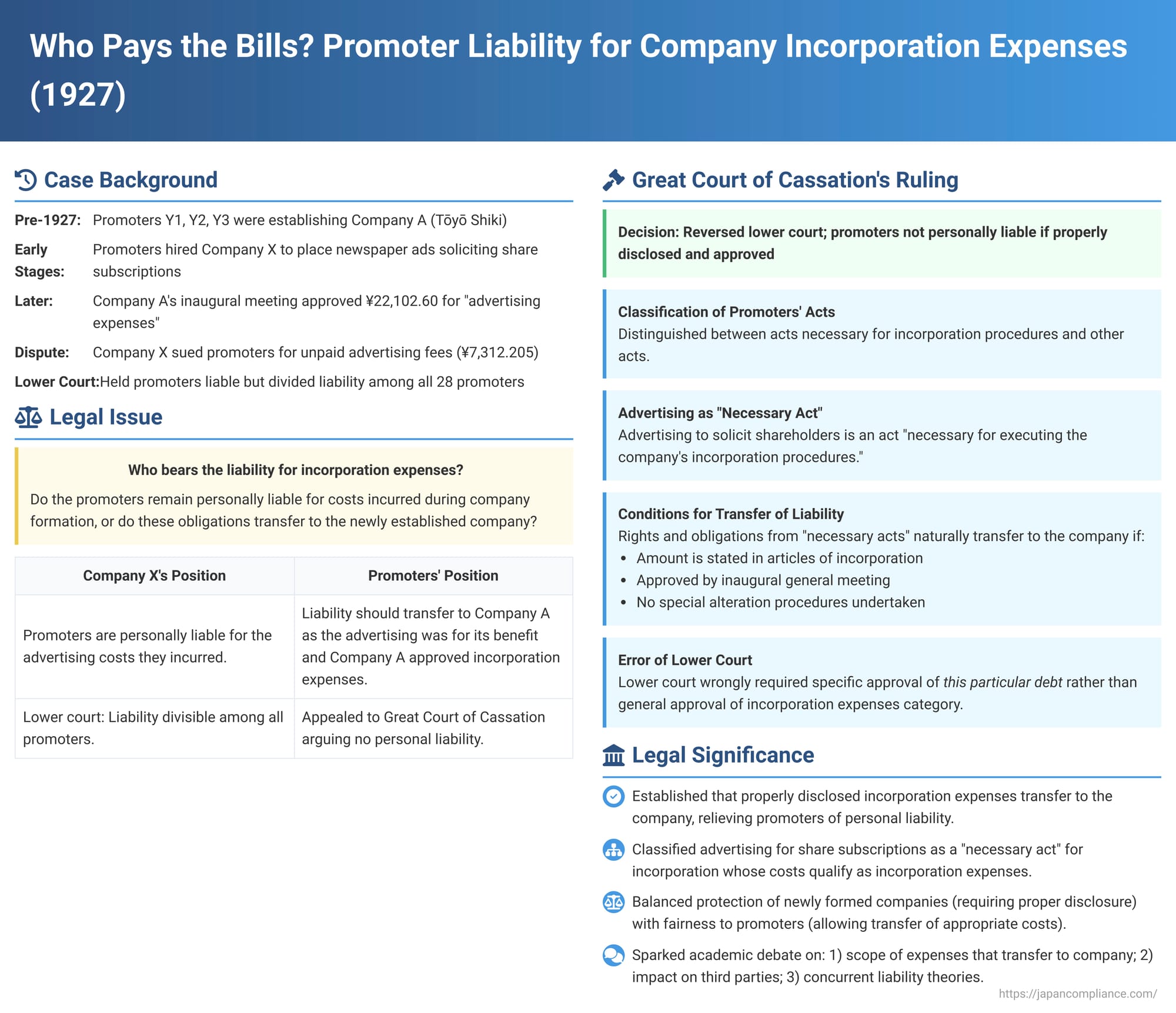

The Facts: Advertising for a New Venture and Unpaid Fees

The case involved Company X, a business engaged in handling newspaper advertising. A group of individuals, including Promoters Y1, Y2, and Y3 (the defendants/appellants in the Daishin'in), were in the process of establishing a new joint-stock company, to be named Company A (Tōyō Shiki Kabushiki Kaisha). As part of their efforts to launch Company A, these promoters engaged Company X to place newspaper advertisements soliciting subscriptions for Company A's shares.

Company X duly carried out the advertising work, and the total fee for these services amounted to 7,312.205 yen. When this amount went unpaid, Company X filed a lawsuit against Promoters Y1, Y2, and Y3, seeking joint and several payment of the outstanding advertising fees.

An important piece of background information was that Company A's inaugural general meeting (創立総会 - sōritsu sōkai), a crucial step in the incorporation process, had approved a sum of 22,102.60 yen specifically designated for "advertising expenses" as part of the company's overall incorporation costs.

The Lower Court's Position: Promoters Held Partially Liable

The lower appellate court (the court immediately preceding the Daishin'in in this case) found that Promoters Y1, Y2, and Y3 were indeed liable for the advertising fees. However, its reasoning was nuanced. It held that the inaugural general meeting of Company A, while approving a general sum for advertising expenses, had not specifically acknowledged or approved the payment of this particular debt owing to Company X directly from the company's funds. In the absence of such specific approval for the direct payment of this individual debt by the company, the lower court concluded that the promoters remained personally liable.

However, the court further ruled that the promoters' liability was not joint and several but rather divisible among all 28 promoters involved in establishing Company A. Consequently, it held Y1, Y2, and Y3 each liable only for their pro-rata share of the debt, which amounted to 261.15 yen each. Dissatisfied with this outcome (presumably still holding them personally liable, albeit for a smaller individual sum), Y1, Y2, and Y3 appealed to the Great Court of Cassation.

The Great Court of Cassation's Ruling: Conditions for Transferring Liability to the Company

The Great Court of Cassation reversed the lower appellate court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. Its judgment laid down important principles regarding the attribution of liabilities incurred by promoters during a company's formation.

1. Classification of Promoters' Acts:

The Court began by distinguishing between two types of acts undertaken by promoters on behalf of a company they are forming:

* Acts necessary for executing the procedures of incorporation.

* Acts not falling into this category.

2. Acts Necessary for Incorporation and Their Intended Effect:

For acts that are "necessary for executing the incorporation procedures" (設立事務の執行に必要なる行為 - setsuritsu jimu no shikkō ni hitsuyō naru kōi), the Court stated that promoters undertake these actions with the specific intention that, once the company is successfully established, all legal effects of these acts (both rights and obligations) will belong to the newly formed company.

3. Conditions for Transfer of Obligations to the Company:

The Daishin'in ruled that if a company is successfully formed, and its inaugural general meeting approves the acts performed by the promoters, then the rights and obligations arising from contracts made by these promoters with third parties concerning such "necessary acts" will, by their nature, naturally transfer to the company. Upon such transfer, the promoters are considered to have exited from those legal relationships, and their personal liability ceases.

4. What Constitutes "Necessary Acts"?

The Court identified key examples of acts necessary for incorporation, such as securing subscriptions for shares and ensuring the first payment of share capital. It referenced its own prior judgments (from Meiji 43 (1910) and Taisho 11 (1922)) which had established that subscription monies and paid-in capital received by the promoter group naturally transfer to the formed company.

5. Advertising for Share Subscriptions as a "Necessary Act":

The Court then specifically addressed the nature of the advertising contract in question. It reasoned that when promoters place newspaper advertisements to solicit shareholders and promise to pay the associated costs, this is fundamentally a method to find subscribers for the company's shares and thereby secure its capital. Therefore, such advertising is, like the acts of securing subscriptions and share payments themselves, an act "necessary for executing the company's incorporation procedures."

6. Advertising Costs as "Incorporation Expenses":

The Daishin'in further classified these advertising costs as "incorporation expenses to be borne by the company" (会社の負担に帰すべき設立費用 - kaisha no futan ni kisu beki setsuritsu hiyō), as contemplated by the Commercial Code (then Article 122, Item 5; later Article 168, Paragraph 1, Item 8 of the pre-2005 Commercial Code; cognate to Article 28, Item 4 of the current Companies Act).

7. Requirements for Transfer of Liability for Incorporation Expenses:

The Court laid down a crucial rule: If the amount of such advertising expenses (as a type of incorporation expense) is stated in the company's articles of incorporation and subsequently approved by the inaugural general meeting, and assuming no special alteration procedures concerning these expenses are undertaken (as per then Commercial Code Article 135, now Companies Act Article 96), then the rights and obligations arising from the advertising contract naturally transfer to the company. In such a scenario, the company becomes liable for paying the advertising fees, and the promoters are entirely relieved of this obligation.

8. Error of the Lower Court:

Applying these principles, the Daishin'in found the lower appellate court's reasoning to be flawed. The lower court had acknowledged that Company A's inaugural meeting approved 22,102.60 yen for advertising costs. The Daishin'in stated that if the 7,312.205 yen claimed by Company X was included within the incorporation expenses that were stated in Company A's articles of incorporation and subsequently approved by its inaugural general meeting, then the obligation to pay this specific advertising fee should have transferred to Company A. Consequently, Promoters Y1, Y2, and Y3 would bear no personal liability for it.

The lower court had erred by insisting that the promoters would remain liable unless the inaugural meeting had specifically and expressly approved that this particular debt to Company X should be paid directly by the company out of the total approved incorporation expenses. The Daishin'in held that this was an incorrect interpretation of the law. The lower court failed to ascertain the critical facts: whether the amount claimed by Company X was indeed covered by the provisions for incorporation expenses in Company A's articles and whether it fell within the scope of expenses approved by the inaugural meeting. This failure constituted an illegal judgment necessitating reversal and remand.

Understanding "Incorporation Expenses" (Setsuritsu Hiyō)

The concept of "incorporation expenses" is central to this ruling.

- Definition: These are expenses deemed necessary for the actual establishment of the company. They are generally distinguished from "business preparatory expenses" (kaigyō junbi kōi), which are costs related to preparing for the company's future business operations rather than its legal formation. Examples of incorporation expenses include rent for a temporary office used during the establishment phase, printing costs for essential documents like share application forms and prospectuses, and, as in this case, advertising costs for soliciting share subscriptions. The advertising fee in question was correctly identified as an incorporation expense.

- Regulation as "Extraordinary Establishment Matter": Under Japanese company law, incorporation expenses that are to be borne by the company are treated as one of the "extraordinary establishment matters" (hentai setsuritsu jikō). These matters, which also include promoters' remuneration, benefits in kind, and pre-incorporation property acquisitions, require disclosure in the company's original articles of incorporation and are typically subject to scrutiny (e.g., by a court-appointed inspector under current law, though the specifics have evolved). This strict regulation is due to the potential for abuse by promoters, which could undermine the company's initial financial foundation. While these are expenses the company should rightly bear, allowing an unlimited amount without oversight could lead to promoters burdening the new company with excessive costs.

- There are exceptions for certain standard, non-discretionary costs like registration taxes and notary fees for articles, which can be borne by the company even without specific mention in the articles, due to their low risk of abuse.

Scholarly Debate and Alternative Views on Liability

The Daishin'in's position in this 1927 case—that properly disclosed and approved incorporation expenses transfer to the company, relieving promoters of liability—has been the subject of considerable academic discussion over the decades.

- Support for the Judgment: Some scholars have concurred with the Court's approach.

- Criticisms of the Judgment's Approach: Many have raised concerns:

- Making the transfer of liability to the company dependent on internal company matters (the content of its articles and the approval of its inaugural meeting) can create uncertainty for third parties who transact with promoters. These third parties may not easily ascertain these internal facts.

- If the total amount of incorporation expenses approved by the inaugural meeting is less than the actual expenses incurred by promoters, it can be difficult to determine which specific contractual obligations transfer to the company and which remain with the promoters.

- In response to the latter point, some suggest that the attribution could be based on the chronological order in which the contracts were made, or that the "approval" by the meeting should be interpreted as an itemized approval of specific expenses, not just a lump sum. However, these suggestions also face criticism: itemized approval is not usually legally required, and proving the sequence of multiple contracts can be problematic.

- Alternative Theories on Liability for Incorporation Expenses: The PDF commentary outlines three main alternative academic approaches:

- All Necessary Expenses Transfer to Company: This view holds that all rights and obligations arising from acts necessary for establishment automatically transfer to the company upon its formation, regardless of strict compliance with disclosure formalities in the articles. If the company ends up bearing expenses that were not properly authorized internally (e.g., amounts exceeding what was disclosed/approved), it can then seek reimbursement from the promoters.

- Only Core Formation Acts Transfer; Others Remain with Promoters: This theory posits that only the legal effects of acts directly related to the formation of the corporate entity itself (such as drafting the articles of incorporation, processing share subscriptions) transfer to the company. Obligations arising from other acts (which would include the advertising debt in this case) remain with the promoters. The promoters can then seek reimbursement from the company, but only up to the amount that has been properly specified in the articles and approved according to legal procedures. Many scholars have supported this view.

- Concurrent Liability of Company and Promoters: Drawing parallels with the liability of unincorporated associations (particularly under German legal influence), this theory suggests that while the debt for incorporation expenses becomes the company's obligation upon formation, this does not automatically release the promoters. Instead, both the company and the promoters could be held concurrently liable to the third party.

- Connection to the "Company-in-Formation" Concept: The debate, especially between theories 1 and 2, is closely linked to the legal concept of the "company-in-formation" (設立中の会社 - setsuritsū no kaisha). This term refers to the entity as it exists during the process of incorporation, before it achieves full legal personality through registration. It's often described as an "embryo" of the future company. Under the "identity theory" (dōitsusei setsu), which is influential in Japanese law, the company-in-formation and the subsequently registered company are seen as substantively the same entity, albeit at different stages of development. Consequently, acts performed by promoters as organs of the company-in-formation, provided they are within the scope of their authority, are considered to bind the fully formed company without needing a separate act of transfer. The core of the debate then shifts to defining the precise scope of this "promoter authority."

- Critiques of the Alternative Theories: Theory 2 (narrow scope of transfer) is criticized by some as undermining the utility of the "identity theory" if most pre-incorporation transactional effects don't pass to the company. Conversely, Theory 1 (broad scope of transfer) is criticized from the perspective of Theory 2 proponents for potentially blurring the lines between acts truly necessary for establishment and "business preparatory acts," thereby risking the new company's financial soundness, which the regulations on extraordinary establishment matters aim to protect.

Evolution of Legal Thought and Modern Implications

This Daishin'in decision from 1927 provides a foundational perspective from an earlier era of Japanese company law. The PDF commentary notes that legal thought and statutory frameworks have evolved since then. Historically, Japanese Commercial Code amendments related to company formation often focused on strengthening the protection of the company's initial capital and financial base. More recent trends in the Companies Act, however, have seen some relaxation of these stringent requirements at the formation stage (e.g., abolition of the minimum capital system, simplification of paid-in capital proof for certain types of incorporation, and easing of regulations on post-incorporation asset acquisitions). This might suggest a reduced emphasis on ensuring a substantial financial base at the very moment of incorporation. However, the commentary also points out that recent amendments have introduced specific liabilities for promoters and directors involved in disguised capital contributions, indicating ongoing concern about founder conduct. The precise impact of these broader statutory shifts on the interpretation of issues surrounding incorporation expenses and promoter liability remains a subject of ongoing legal analysis.

Conclusion

The Great Court of Cassation's 1927 ruling in this advertising fee case established an important early benchmark for attributing incorporation expenses in Japanese company law. It clarified that obligations for expenses necessary for a company's establishment, such as advertising for share subscriptions, could transfer from the promoters to the newly formed company, provided these expenses were properly disclosed in the company's articles of incorporation and approved by its inaugural general meeting. In such cases, the promoters would be relieved of personal liability. While the specifics of company law have evolved significantly, this foundational decision and the ensuing scholarly debate highlight the enduring legal challenge of balancing the practical needs of company formation, the protection of third parties who deal with promoters, and the financial integrity of the nascent corporate entity.