Who Owns an Incomplete Building Finished by Another? A Japanese Supreme Court Look at Accession vs. Processing

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Judgment of January 25, 1979 (Showa 54) (Case No. 872 (O) of 1978 (Showa 53))

Subject Matter: Claim for Vacation of House (家屋明渡請求事件 - Kaoku Akewatashi Seikyū Jiken)

Introduction

This article examines a 1979 Japanese Supreme Court judgment that addresses a complex issue in property law: determining ownership when a building, partially constructed by one contractor, is subsequently completed by a different party using their own materials and labor. The case delves into whether such a scenario should be governed by the rules of accession of movables (where one thing is attached to another) or by the rules of processing (where work is done on materials to create a new thing). The Supreme Court's decision to apply the principles of processing by analogy provides important guidance for resolving ownership disputes in construction projects that change hands mid-stream.

The dispute involved X (appellant/plaintiff), the heir of B (the initial subcontractor), and Y (appellee/defendant), the individual who had commissioned the building's construction. The original main contractor was Company A, and the completing contractor was Company C.

Factual Background

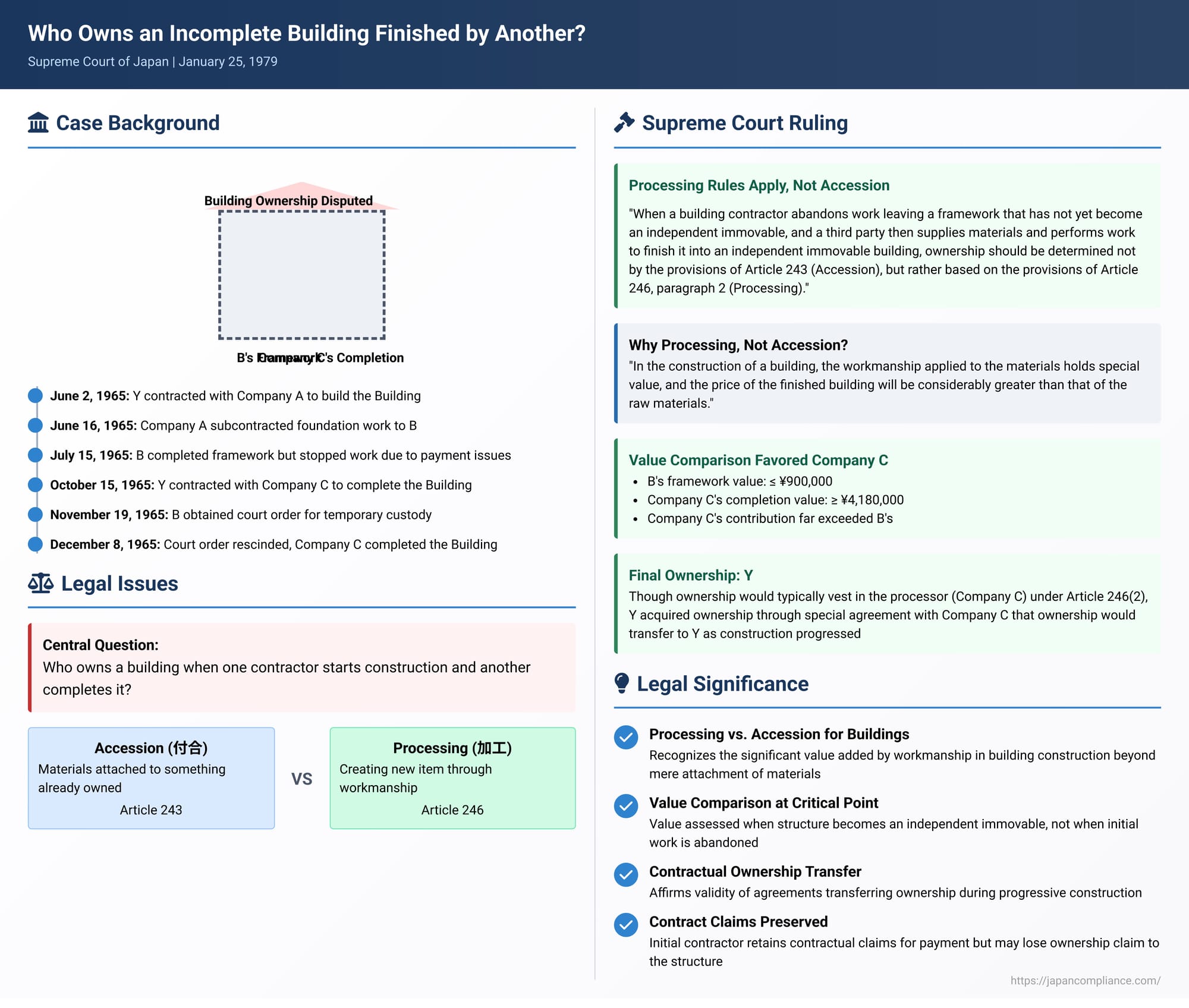

On June 2, 1965, Y (the building owner) contracted with Company A to construct the building in question (the "Building") for a price of JPY 6.22 million. Company A, while intending to perform some work itself, subcontracted significant portions, including site preparation and foundation work, to B (X's husband, deceased during the first instance trial) on June 16, 1965. This subcontract stipulated that B would procure all materials for his portion of the work for a price of JPY 3.8 million, with payments to be made by Company A as work progressed (e.g., at groundbreaking, framework completion).

B commenced work immediately and by around July 15, 1965, had completed the framework erection (棟上げ - muneage) and finished laying the roof underlayment. Although Company A had received JPY 2.13 million from Y, checks and promissory notes issued by Company A to B were all dishonored. Consequently, B stopped further work, leaving the roof untiled and the rough walls unplastered, and notified Company A of the rescission of his subcontract.

Around October 1965, Y (the building owner) and Company A mutually agreed to terminate their main construction contract. On October 15, Y then contracted with a new company, Company C, to continue and complete the construction, with a special agreement that ownership of the building, as it progressed, would belong to Y.

On November 19, 1965, B obtained a provisional disposition order placing the partially constructed Building under court officer custody, temporarily halting Company C's work. By this time, the structure, though unfinished, had already reached a state where it could be considered an independent building (an immovable). This provisional disposition was rescinded on December 8, 1965, and Company C resumed and completed the construction of the Building.

B (and subsequently his heir X) sued Y, claiming ownership of the completed Building and demanding its vacation and damages equivalent to rent. X argued that the Building had become an independent immovable at the point B stopped work, with ownership vesting primitively in B (as B supplied the materials for his work). X further argued that Company C's subsequent work and materials acceded to B's structure under Civil Code Article 242.

The first instance court, while finding that the structure was still a movable when B stopped work, applied Article 246 (Processing of Movables) by analogy to determine ownership of the completed building. The appellate court also applied Article 246(2) by analogy. It compared the value of B's work (estimated at no more than JPY 900,000) with the value of the structure as it stood when the provisional disposition was executed after Company C had worked on it (estimated at a minimum of JPY 4.18 million). Finding Company C's contribution to be far greater, it held that ownership did not belong to B and dismissed X's appeal. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, upholding the lower courts' conclusion that ownership of the completed Building did not belong to B (or X as heir). However, it clarified the legal reasoning for applying the principles of processing.

The Court held:

"When a building contractor, in the course of construction, abandons work leaving a framework that has not yet become an independent immovable, and a third party then supplies materials and performs work to finish it into an independent immovable building, the ownership of the said building should be determined not by the provisions of Article 243 of the Civil Code (Accession of Movables), but rather based on the provisions of Article 246, paragraph 2 (Processing of Movables)."

The Court's rationale for preferring the analogy to "processing" (加工 - kakō) over "accession" (付合 - fugō) was:

"In such a case, unlike situations where movables are simply attached to other movables and the value of the workmanship applied there can be disregarded, in the construction of a building like the one in question, the workmanship applied to the materials holds special value, and the price of the finished building will be considerably greater than that of the raw materials. Therefore, it is more appropriate to determine ownership based on the provisions for processing in the Civil Code."

Applying this to the facts:

- Company C's Work as "Processing": The work done by Company C was not mere repair but involved adding workmanship to the framework B had built, thereby "manufacturing" a new immovable property – the Building.

- Determining Ownership under Article 246(2) (Processing): When determining ownership based on Article 246, paragraph 2 (which states that if the value of the workmanship significantly exceeds the value of the materials, ownership of the processed thing belongs to the processor, provided the processor supplied part of the materials), the comparison should be made based on the state of the building as it was finished up to the point it legally became an independent immovable due to Company C's work (i.e., by November 19, 1965, the date of the provisional disposition execution), not based on the state when B's work was merely a framework.

- Value Comparison: Comparing the value of the work and materials provided by Company C up to that point (at least JPY 4.18 million) with the value of the framework B had constructed (not exceeding JPY 900,000), the former far exceeded the latter.

- Ownership Vests in Processor (Company C), then in Commissioning Party (Y): Therefore, ownership of the processed item (the Building) should belong to the processor, Company C. However, since Company C had a special agreement with Y (the building owner who commissioned the work) that ownership of the building would belong to Y as work progressed, the ultimate ownership of the Building vested in Y.

The Supreme Court thus found the appellate court's conclusion (that B/X did not own the building) to be correct, and saw no error in its judgment dismissing X's claim.

Analysis and Implications

This 1979 Supreme Court judgment provides important guidance on determining ownership when an unfinished building framework is completed by a party other than the one who started it.

- "Processing" (Kakō) by Analogy, Not "Accession" (Fugō): The Court clearly favored applying the principles of "processing" (Article 246 of the Civil Code) by analogy over "accession of movables" (Article 243) in such construction scenarios. This is because the act of completing a building involves significant value-adding workmanship (加工 - kakō) that goes beyond simple attachment of materials. The identity of the thing changes from mere materials or a basic frame to a new, more valuable object (a building).

- Valuation Point for Determining Ownership: When applying Article 246(2) by analogy, the crucial point for comparing the value of the original materials/framework and the value added by the subsequent processor is the moment the structure achieves the legal status of an independent immovable property as a result of the processor's efforts. This is a more refined approach than looking only at the value of the initial abandoned framework.

- Importance of Contractual Agreements on Ownership: The case highlights the significance of contractual stipulations regarding ownership during construction. The agreement between Y (the owner) and Company C (the completing contractor) that ownership would vest in Y as work progressed was key to Y ultimately being recognized as the owner, even though Company C was deemed the "processor" whose contribution was greater. Without such an agreement, Company C might have been deemed the owner based on the processing rules alone (subject to Y's potential claims).

- Protection of the Party Making the Predominant Contribution: The principle underlying Article 246(2) is that ownership of a newly created or significantly altered item should generally go to the party whose contribution (in terms of materials or the value added by workmanship) is predominant. This case applies that principle to building construction.

- Distinction from Accession to Land: The PDF commentary accompanying this case notes that Japanese law generally considers buildings to be separate immovables from the land they stand on; they do not accede to the land (unlike in some other legal systems). This judgment operates on that premise, focusing on the ownership of the building structure itself, which begins as movable materials and, through construction, becomes an independent immovable. The question was who owned this newly created immovable.

- Rights of the Initial Contractor/Subcontractor: While B (the initial subcontractor) lost ownership of the framework he built because it was "processed" by Company C into a new building whose ownership vested in Y (via Company C), B would still generally have contractual claims against Company A (the main contractor who defaulted on payment) for the work he performed and materials he supplied. He might also have a claim for compensation (償金請求権 - shōkin seikyūken) under Article 248 of the Civil Code against the party who ultimately acquired ownership of the value he contributed (Y, through Company C), if he cannot recover from Company A. This judgment focuses only on the ownership of the completed building.

This decision provides a framework for analyzing ownership in cases of interrupted and subsequently completed construction projects. By applying the rules of "processing" by analogy, it emphasizes the value added by workmanship and aims to attribute ownership based on the predominant contribution, while also respecting contractual agreements between the parties involved in the completion.