Who Owns AI-Generated Works in Japan? Copyright, Authorship & Article 2 Criteria Explained

TL;DR

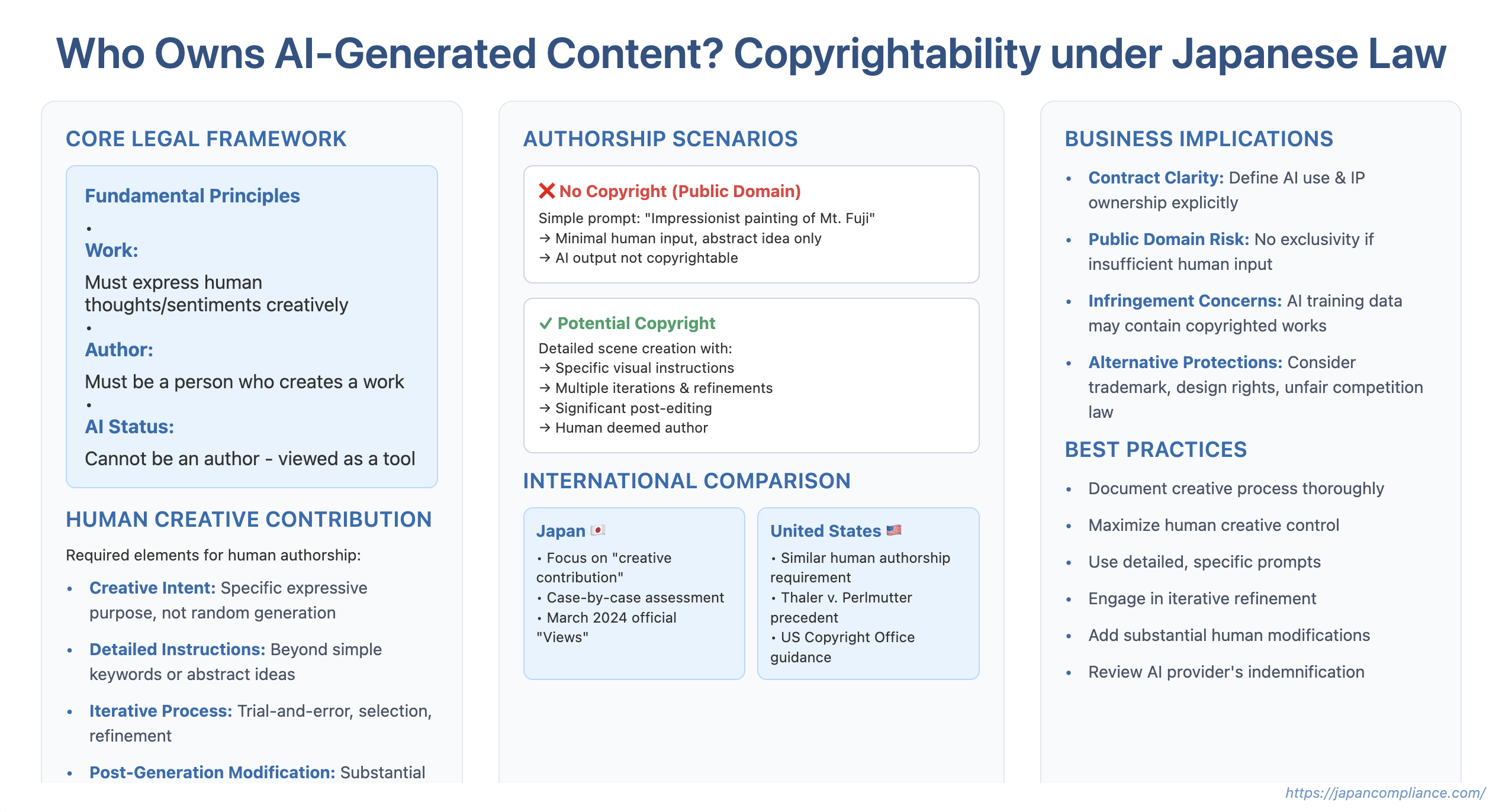

- Under Japan’s Copyright Act, AI itself cannot be an “author”; copyright protection hinges on a human’s “creative contribution.”

- Purely autonomous AI outputs fall into the public domain; human-guided outputs may be protected if the user adds sufficient creative input.

- Businesses must document prompts, iterative edits and post-generation modifications to secure ownership or gauge public-domain risk.

Table of Contents

- Foundational Concepts: "Work" and "Author" in Japanese Copyright Law

- The AI as Author? The Japanese Stance

- Human Authorship: The Decisive Factor of "Creative Contribution"

- Illustrative Scenarios

- Ownership and Implications

- International Comparisons: The US Approach

- Business Considerations

- Conclusion

The rapid advancement of generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) has opened up new frontiers in creativity, enabling the production of text, images, music, and code at an unprecedented scale and speed. However, this technological leap also raises fundamental questions for intellectual property law, particularly copyright. Can a piece of art created by an AI be copyrighted? If so, who is the author – the AI itself, the user who prompted it, or the developer who trained the AI?

Globally, legal systems are grappling with these questions. Japan, like other jurisdictions, approaches this issue through the lens of its existing Copyright Act. While the technology is new, the core principles of Japanese copyright law provide a framework for analysis, emphasizing the necessity of human creativity for protection.

Foundational Concepts: "Work" and "Author" in Japanese Copyright Law

To understand the copyright status of AI-generated content in Japan, we must first look at the fundamental definitions within the Japanese Copyright Act:

- Work (著作物 - chosakubutsu): Defined in Article 2, paragraph (1), item (i) as "a production in which thoughts or sentiments are expressed in a creative way and which falls within the literary, scientific, artistic or musical domain." The key elements are the creative expression of human thoughts or feelings.

- Author (著作者 - chosakusha): Defined in Article 2, paragraph (1), item (ii) as "a person who creates a work."

These definitions intrinsically link copyright protection to human intellectual creation involving "thoughts or sentiments."

The AI as Author? The Japanese Stance

Based on these definitions, the prevailing view in Japan, consistent with early governmental committee reports and reaffirmed in the Agency for Cultural Affairs' March 2024 "Perspectives Regarding AI and Copyright" (the "Views"), is that an AI cannot be an author under current law. An AI lacks legal personality and the capacity for "thoughts or sentiments" in the human sense required by the definition of a "work." Consequently, content generated purely autonomously by an AI, without the requisite human involvement, does not qualify as a "work" under the Japanese Copyright Act and is therefore not eligible for copyright protection. The AI is considered a tool, akin to a paintbrush or a camera, rather than a creator in its own right.

Human Authorship: The Decisive Factor of "Creative Contribution"

Since the AI itself cannot be the author, the central question becomes: can the human user who interacts with the AI be considered the author of the generated output? The answer under Japanese law depends on whether the human's involvement constitutes a sufficient "creative contribution" (創作的寄与 - sōsaku-teki kiyo) to the final output's expressive elements. If the human's input and guidance are substantial enough to be recognized as the creative force behind the work, with the AI merely assisting in its execution, then the human can be deemed the author.

The "Views" document provides guidance on assessing whether human involvement reaches the threshold of creative contribution necessary for authorship. It suggests considering the entire process, including:

- Creative Intent (創作意図 - sōsaku ito): Did the human user have the intention to create a specific piece of expression, rather than merely generating random outputs?

- Instructions/Prompts (指示 - shiji): What was the nature of the human input? Were the prompts simple keywords or abstract ideas (which are generally not protectable), or were they detailed, specific instructions that dictated concrete creative elements of the final output (e.g., specific compositions, color palettes, character descriptions, plot points, musical arrangements)? Detailed instructions guiding the expressive outcome are more likely to support a finding of creative contribution.

- Iterative Process and Selection: Did the human engage in a significant process of trial-and-error? This could involve generating multiple outputs based on varying prompts, critically selecting specific outputs based on creative judgment, and providing iterative feedback or modifications to refine the results towards the intended creative expression. Simply choosing one option from a few generated outputs might not be sufficient if the selection itself lacks creative input.

- Post-Generation Modification: Did the human significantly modify or add to the AI-generated output using traditional creative tools (e.g., editing software, musical instruments)? Substantial, creative modifications can contribute to establishing human authorship over the final, modified work. Minor edits or trivial changes are unlikely to suffice.

Essentially, the analysis focuses on whether the human provided the core creative spark and exercised sufficient control over the final expressive form of the output, even if an AI tool was used in the process.

Illustrative Scenarios

Consider these contrasting scenarios:

- Scenario A (Likely No Human Authorship/No Copyright): A user enters a simple prompt like "Impressionist painting of Mount Fuji at sunset" into an image generator. The AI produces an image. The user accepts the first result with no further interaction or modification. Here, the prompt represents an unprotectable idea, and the user made no significant creative choices or contributions to the specific expression generated by the AI. The output would likely not be considered a copyrighted work in Japan, falling into the public domain.

- Scenario B (Potentially Human Authorship/Copyrightable): A user wants to create a specific scene for a graphic novel. They provide highly detailed prompts to an AI image generator, specifying character appearance, pose, background elements, lighting, camera angle, and artistic style. They generate dozens of images, iteratively refining the prompts ("make the character look more determined," "change the lighting to be more dramatic," "add these specific background details"). They select the most suitable image based on their artistic vision and then significantly modify it in image editing software, redrawing elements, adjusting colors, and integrating it seamlessly into their graphic novel layout. In this case, the detailed instructions, the iterative refinement process, the creative selection, and the substantial post-generation editing could collectively amount to sufficient "creative contribution" for the user to be considered the author of the final image (or at least the creative elements they added/directed).

The determination is highly fact-specific and depends on the degree and nature of human intervention in the creative process.

Ownership and Implications

The determination of authorship directly impacts copyright ownership:

- Human Author Identified: If a human user's creative contribution is deemed sufficient to qualify them as the author, they (or their employer, if created within the scope of employment under standard work-for-hire rules – Article 15 of the Copyright Act) own the copyright in the generated work (or the human-authored portions thereof). They can control its reproduction, distribution, adaptation, etc., subject to the usual limitations.

- No Human Author Identified: If the human involvement does not meet the threshold for creative contribution, the AI-generated output is not considered a "work" under the Copyright Act. It therefore has no author and no copyright protection. Such works fall into the public domain in Japan, meaning anyone can freely use, copy, or modify them without permission under copyright law (though other laws like trademark or unfair competition might still apply depending on the context).

International Comparisons: The US Approach

The question of AI and copyright is being debated globally, with varying nuances. In the United States, the US Copyright Office has consistently maintained that copyright protection requires human authorship. Landmark administrative decisions and court rulings, such as in the Thaler v. Perlmutter case (where the D.C. Circuit affirmed the Copyright Office's refusal to register a work listing an AI as the author), have solidified the principle that a work must originate from a human mind to be copyrightable under US law.

The US Copyright Office guidance clarifies that while AI can be used as a tool to assist human creativity, the resulting work is only copyrightable if a human exercised sufficient creative control over its expression. Merely providing prompts to a generative AI system is generally considered insufficient for authorship of the AI's output, although significant selection and arrangement of AI-generated material, or substantial modification of it by a human, could result in a copyrightable work authored by the human. The focus, similar to Japan, remains on the centrality of human creativity.

Business Considerations

The copyright status of AI-generated content has significant practical implications for businesses:

- IP Ownership in Contracts: When commissioning work involving AI (e.g., graphic design, marketing copy), contracts should clearly define expectations regarding the use of AI tools and specify who owns the intellectual property rights in the final deliverables, accounting for the possibility that purely AI-generated elements might lack copyright protection.

- Using AI Outputs: Businesses using AI-generated content must assess the risk associated with its copyright status. If the content is likely in the public domain (due to insufficient human creative contribution), it can be used freely under copyright law but offers no exclusivity. Competitors could use the same or similar outputs.

- Risk of Third-Party Infringement: Independent of whether the output is copyrightable, the AI generation process might itself infringe third-party copyrights if the AI was trained on infringing data or if the output incorporates substantial portions of existing copyrighted works from its training set. Using AI-generated content carries this inherent risk, which is separate from the authorship question. Due diligence regarding the AI tool provider's practices and potential indemnification clauses may be warranted.

- Alternative Protections: If copyright is unavailable, businesses might explore other forms of IP protection for assets incorporating AI-generated elements, such as trademark protection for logos or brand names generated with AI assistance, or design rights for product aesthetics. Unfair competition law might also offer recourse against certain types of misappropriation.

Conclusion

Under current Japanese copyright law, authorship and the possibility of copyright protection for AI-generated content are firmly tied to human creativity. AI systems are viewed as sophisticated tools, but they cannot be authors. Copyright protection arises only when a human user provides sufficient "creative contribution" – through detailed instructions, iterative refinement, creative selection, or substantial modification – to be considered the true author of the expressive work. Where human input is minimal or amounts only to an abstract idea, the resulting AI output is unlikely to qualify for copyright protection in Japan and will likely reside in the public domain.

For businesses leveraging generative AI, this necessitates a careful evaluation of their creation processes. Maximizing human creative control and input is key not only to potentially securing copyright in the output but also to shaping unique and valuable results. As AI technology continues to evolve, offering potentially greater levels of user control or exhibiting more autonomous behaviour, the legal interpretations surrounding creative contribution and authorship will undoubtedly continue to be refined by regulators, courts, and industry practice.

- Japan’s Article 30-4: Navigating AI Training Data and Copyright Exceptions

- Decoding Japanese IP Law: How Judicial Interpretation Shapes Patent, Trademark and Copyright Cases

- Balancing Innovation and Security: Strategic IP and R&D Adjustments Under Japan's Patent Non-Disclosure System

- General Understanding on AI and Copyright in Japan – Overview (Agency for Cultural Affairs, May 2024, PDF)