Who Cares? Japan's Supreme Court Defines the "Concerned Person" in Corporate Kidnapping

Case Title: Case of Kidnapping for Ransom, etc.

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Decision Date: March 24, 1987

Introduction

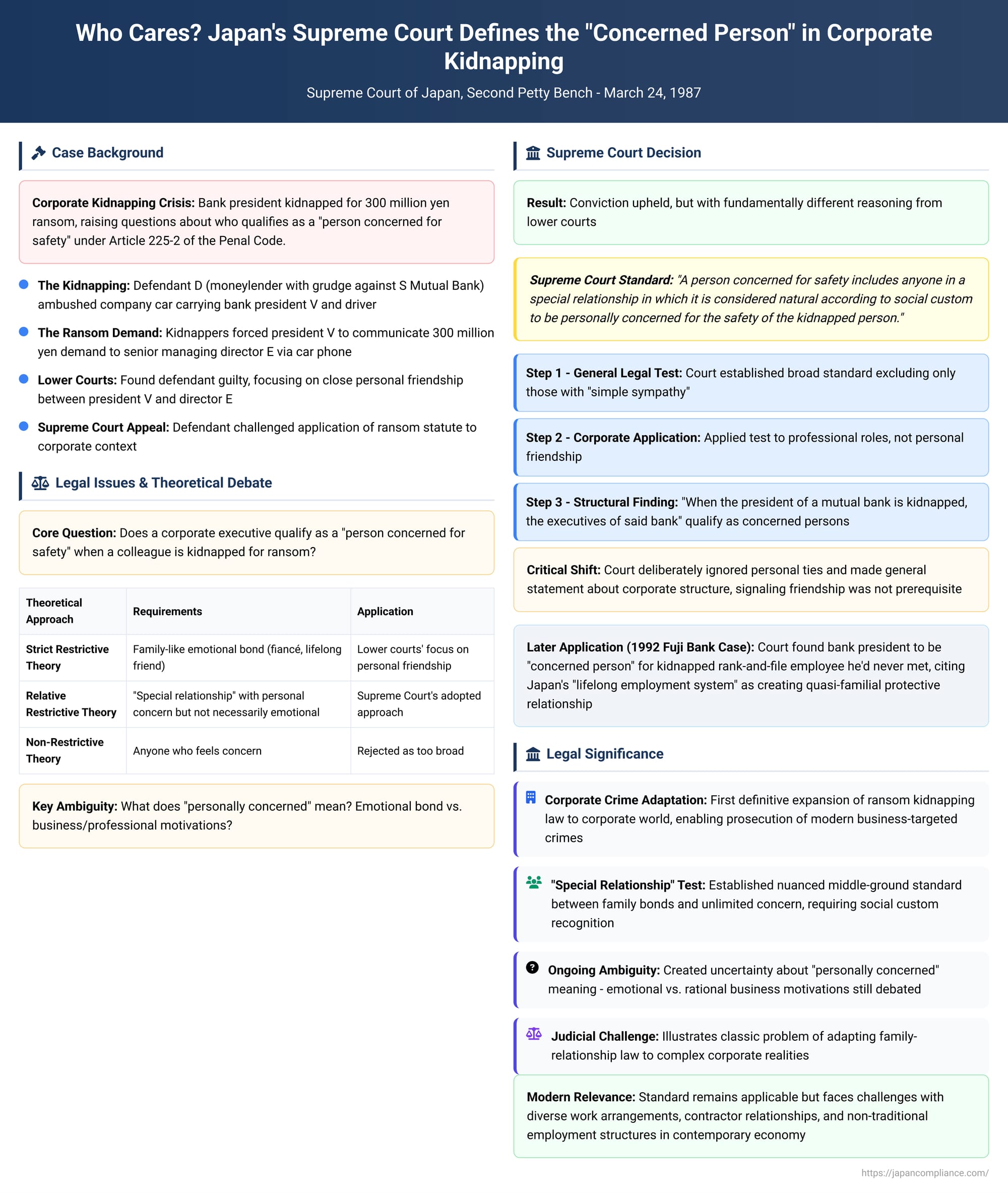

The crime of kidnapping for ransom has evolved over time. What once primarily targeted the families of the wealthy has expanded to include a more modern and complex target: the corporation. When a company executive or employee is abducted and a ransom is demanded from their employer, a unique legal question arises. Japan's law against kidnapping for ransom, Article 225-2 of the Penal Code, was drafted to punish criminals who exploit the anguish of a victim's "relatives or other persons concerned for the safety of the kidnapped person." But does a corporate executive, whose relationship with a colleague is professional, fit the description of a "person concerned for safety" in the same way as a family member?

This question was at the heart of a landmark 1987 Supreme Court decision. The case, involving the kidnapping of a bank president, forced the Court to interpret this critical phrase and, in doing so, to adapt a law rooted in family ties to the impersonal world of corporate crime. The Court's ruling broadened the scope of the law but also created a nuanced legal standard that continues to be debated today.

The Facts: A Corporate President Held for Ransom

The defendant, D, a moneylender with a long-standing grudge against S Mutual Bank, conspired with accomplices to kidnap its president. They successfully ambushed the company car carrying the bank's president, V, and his driver. The two men were taken to a hotel room and held captive. From there, the kidnappers used a car phone to force the terrified president to communicate a ransom demand to E, a senior managing director at the bank. The demand was for 300 million yen.

When the case went to trial, the lower courts found the defendant guilty of kidnapping for ransom. In affirming that the senior executive, E, was a "person concerned for the safety" of the president, V, the lower courts highlighted the specific and close personal relationship between the two men; they had joined the bank at the same time and maintained a strong friendship over the years. The defendant appealed, challenging the application of the ransom statute to this corporate context.

The Supreme Court's Definitive—and Broad—Ruling

The Supreme Court upheld the conviction but did so with significantly different reasoning than the lower courts. It set aside the lower courts' focus on the individual friendship and instead established a general legal test for who qualifies as a "person concerned for the safety."

The Court ruled that the category includes anyone in a "special relationship in which it is considered natural according to social custom to be personally concerned for the safety of the kidnapped person." This standard, the Court noted, excludes mere third parties who feel only "simple sympathy."

Most importantly, the Court then applied this test not to the specific friendship between V and E, but to their professional roles. It stated that when the president of a mutual bank is kidnapped, "the executives of said bank" as a group fall into this category of concerned persons. By deliberately ignoring the personal ties and making a general statement about corporate structure, the Supreme Court signaled that a close, family-like friendship was not a necessary prerequisite.

The "Restrictive Theory" Debate: How Special is the 'Special Relationship'?

The Supreme Court’s ruling is best understood as an attempt to navigate a long-standing scholarly debate over how broadly to interpret the phrase "relatives or other persons concerned for safety."

- The Strict Restrictive Theory: This view argues that the "other persons" must have a bond of affection and loyalty as strong as that of a close relative (e.g., a fiancé or a lifelong best friend). The relationship is fundamentally emotional and non-economic (Gemeinschaft). The lower courts' focus on the personal friendship between the executives reflected this stricter approach.

- The Relative Restrictive Theory: This view, which the Supreme Court's decision is seen as adopting, seeks a middle ground. It acknowledges that the category must be limited (thus rejecting a "non-restrictive theory" where anyone who feels concern would qualify) but does not confine it to family-like bonds. This approach allows the law to adapt to modern realities like corporate kidnappings.

Unpacking "Personally Concerned": Emotion vs. Economics

The Court’s new standard, while providing a path to convict in corporate cases, introduced its own ambiguity with the phrase "personally concerned" (mi ni natte). Does this require genuine, personal, emotional concern, or can it encompass motivations rooted in business?

- One view, supported by the case's judicial rapporteur, is that "sincere concern" can stem from professional or business-related (Gesellschaft) motives, such as the need to protect the company's reputation or maintain employee morale.

- The commentary author challenges this, arguing that the phrase "personally concerned" strongly implies an emotional, non-economic bond. To include business motives would risk collapsing the standard into the rejected "non-restrictive theory," since a company will almost always have a rational, economic reason to be concerned about a kidnapped employee.

This tension was evident in a later lower court case, the 1992 "Fuji Bank" kidnapping. There, a court found the president of a massive bank to be a "concerned person" for a kidnapped rank-and-file employee whom he had never met. The court justified this not on economic grounds, but by citing Japan's "lifelong employment system" as creating a special, quasi-familial, protective relationship between the company and its employees. This demonstrates the continued judicial effort to find a personal, emotional-like basis for the relationship, even in a corporate context.

Critique and Lingering Problems

The Supreme Court's middle-ground approach, while solving the immediate problem of corporate kidnappings, has been criticized for creating new uncertainties. In a modern economy with diverse work arrangements, its application is unclear. For instance, would the rule apply to a company that relies on contractors or has high employee turnover, or only to those with a more traditional, "lifelong employment" culture? The commentary author suggests that such distinctions seem arbitrary when the underlying corporate interests, like brand image, are the same.

The author argues that a more textually faithful interpretation of the law would be a return to the "Strict Restrictive Theory." The reason kidnapping for ransom carries a heavier penalty is that it preys on the unique vulnerability of loved ones, who feel compelled to meet irrational demands out of a deep, personal bond. This heightened culpability, it is argued, only truly applies when such a relationship is being exploited.

Conclusion

The 1987 Supreme Court decision was a pivotal moment in Japanese criminal law. It definitively expanded the reach of the kidnapping-for-ransom statute to the corporate world by establishing the "special relationship" test. By moving beyond the need for a strict, family-like bond, the Court enabled prosecutors to tackle a modern form of crime. However, in crafting this middle ground, the Court introduced a new layer of ambiguity centered on the meaning of being "personally concerned," leaving a legacy of legal debate over whether the foundation of the crime rests on emotional bonds or can extend to the sincere but rational concerns of a business entity. The decision reflects a classic judicial challenge: adapting a law conceived for personal relationships to the complex and evolving realities of corporate life.