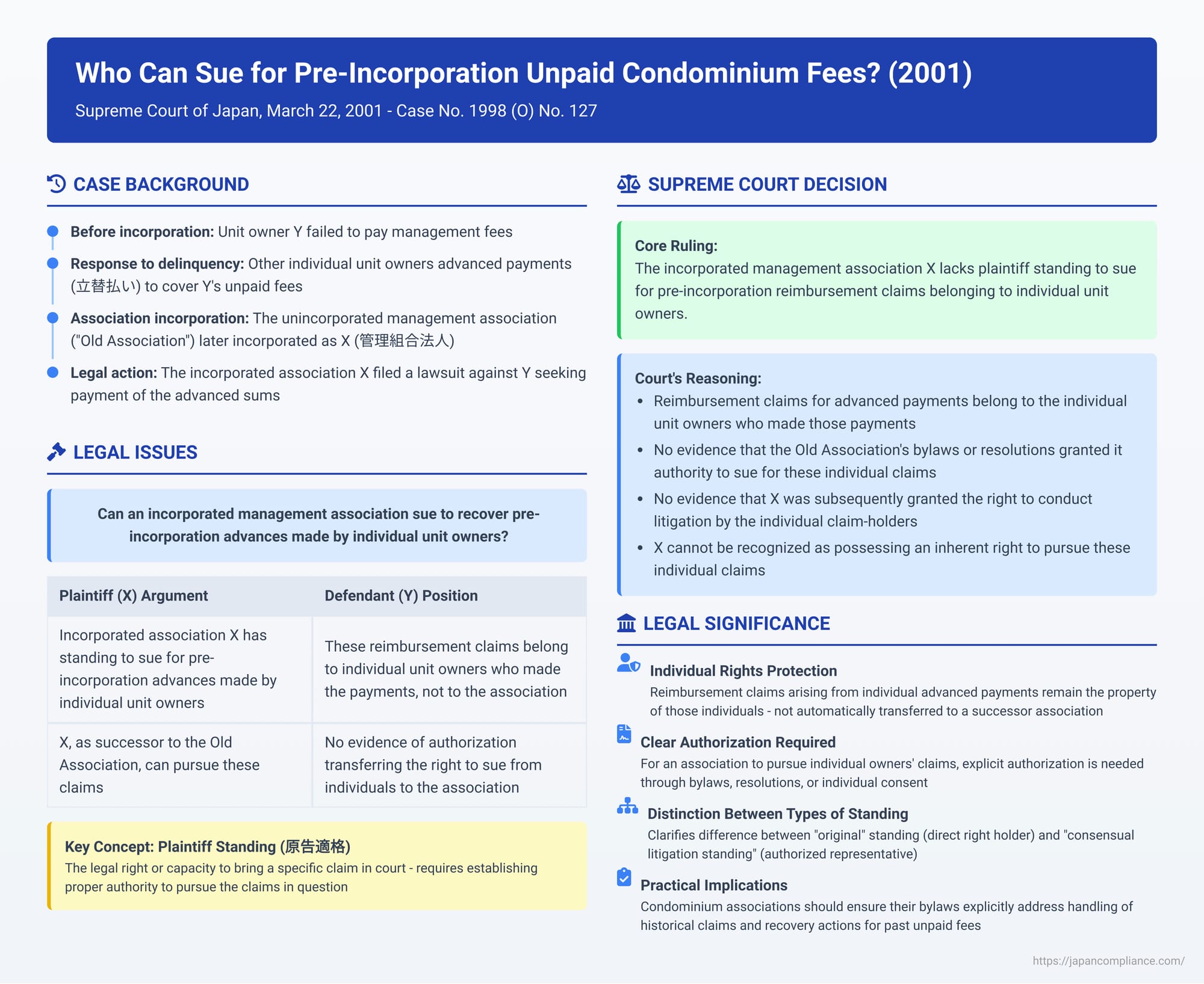

Who Can Sue for Pre-Incorporation Unpaid Condominium Fees Advanced by Members? A 2001 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Plaintiff Standing

Date of Judgment: March 22, 2001

Case Number: 1998 (O) No. 127 (Supreme Court, First Petty Bench)

Introduction

In Japanese condominiums, the smooth operation and maintenance of the building rely heavily on the timely payment of management fees, repair reserve contributions, and other necessary charges by unit owners. When a unit owner becomes delinquent, it can create financial shortfalls. Sometimes, other conscientious unit owners or the (then unincorporated) management association might step in to cover these unpaid amounts to ensure essential services continue. This act of covering another's debt gives rise to reimbursement claims. A crucial legal question arises if the management association later incorporates: can this newly incorporated body sue to recover these past advances made by individual members before the association gained formal legal personality?

This issue of plaintiff standing (原告適格 - genkoku tekikaku) was at the heart of a Supreme Court decision on March 22, 2001. The case examined whether an incorporated management association had the right to sue a delinquent unit owner for sums that other unit owners had paid on their behalf prior to the association's incorporation.

Facts of the Case

The dispute involved Y, a unit owner in "Condominium A," who had failed to pay various assessed charges, including management fees, repair reserve contributions, exclusive use fees (for parking, etc.), and water charges (collectively referred to as "management fees, etc."). Due to Y's delinquency, other unit owners in Condominium A had paid these amounts on Y's behalf (a practice known as 立替払 - tatekaebarai, or advance payment).

These delinquencies by Y and the subsequent advance payments by other unit owners occurred over a period that spanned both before and after the original, unincorporated management association of Condominium A (referred to as the "Old Association") transitioned into an incorporated management association, X (管理組合法人 - kanri kumiai hōjin).

X, the newly incorporated management association, subsequently filed a lawsuit against Y. X sought to recover the management fees, etc., that Y had failed to pay and which other unit owners had advanced. The central legal contention that reached the Supreme Court concerned X's plaintiff standing to sue for the recovery of those amounts that were advanced by individual unit owners before X itself was formally incorporated.

Lower Court Rulings:

- First Instance Court: This court affirmed X's plaintiff standing, likely on the basis of "consensual litigation standing" (任意的訴訟担当 - nin'iteki soshō tantō, where one party is authorized to conduct litigation on behalf of another). It partially granted X's claim against Y.

- High Court (Appellate Court): The High Court took a different view regarding the pre-incorporation advances and dismissed X's suit concerning these amounts. Its reasoning was as follows:

- The specific legal nature of the claim for the advanced sums was identified as reimbursement claims (求償金債権 - kyūshōkin saiken). These were rights held by those who paid Y's debts to be reimbursed by Y.

- Critically, these reimbursement claims belonged to the individual unit owners who had made the advance payments out of their own pockets. These rights did not belong to the Old Association as an entity.

- Consequently, the Old Association did not inherently possess plaintiff standing to sue for these individual reimbursement claims.

- The High Court found no evidence of any provisions in the Old Association's bylaws (規約 - kiyakku) or any resolutions from its general meetings (集会 - shūkai) that would have granted the Old Association the specific authority (訴訟追行権 - soshō tsuikōken, or right to conduct litigation) to pursue these particular reimbursement claims on behalf of the individual paying members.

- Furthermore, there were no other factual circumstances presented that could establish plaintiff standing for either the Old Association or its successor, X (the incorporated association), with respect to these pre-incorporation claims.

X, the incorporated management association, appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated March 22, 2001, dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was concise:

- It stated that it found no error in the High Court's ascertainment of the facts based on the evidence presented.

- Based on these established facts, the Supreme Court agreed with the High Court's fundamental determination that the reimbursement claims in question (along with any associated claims for damages due to late payment) belonged to the individual unit owners who had originally made the advance payments.

- The Supreme Court then concluded that it could not recognize X (the incorporated management association) as either possessing an inherent right to conduct litigation for these specific individual claims or as having been granted such a right by the individual claim-holders.

- Therefore, the High Court's judgment – which held that X's lawsuit seeking payment of these specific pre-incorporation reimbursement claims was unlawful (不適法 - futekihō) due to X's lack of plaintiff standing and should consequently be dismissed – was correct and justifiable.

The Supreme Court found no violation of law in the High Court's decision and rejected X's arguments, which it characterized as either disagreeing with the High Court's findings of fact (a matter within the High Court's purview) or advancing unique legal arguments unsupported by law.

Analysis and Broader Implications

This Supreme Court decision, while brief, touches upon complex issues of plaintiff standing, particularly as it applies to condominium management associations in their various forms. To understand its implications, it's helpful to consider the different ways plaintiff standing is established in Japanese civil procedure.

1. The Concept of Plaintiff Standing (当事者適格 - tōjisha tekikaku):

Plaintiff standing refers to the legal qualification of a party to initiate and pursue a specific lawsuit concerning a particular subject matter and to be the recipient of a judgment on the merits of that case. It's a crucial procedural hurdle. Standing can generally be categorized as:

- "Original" or "Primary" Standing (本来的な原告適格 - honrai-teki na genkoku tekikaku):

- This typically belongs to the person who claims to be the direct holder of the right in dispute (e.g., the creditor in a debt claim, the owner in a property dispute).

- Some legal theories also extend primary standing to a party who, while not the formal holder of the legal right, claims to be its substantive beneficiary.

- "Special" or "Third-Party" Litigation Standing (訴訟担当 - soshō tantō):

- This occurs when a third party (who is not the original holder of the right) is granted the legal authority to sue on behalf of the original right-holder. A key feature is that the final judgment in such a lawsuit is binding on the original right-holder.

- Statutory Litigation Standing (法定訴訟担当 - hōtei soshō tantō): This type of standing is conferred directly by law, irrespective of the wishes of the original right-holder. Examples include a bankruptcy trustee suing on behalf of the bankrupt estate.

- Consensual Litigation Standing (任意的訴訟担当 - nin'iteki soshō tantō): This standing is based on authorization from the original right-holder. A common example is an "appointed party" (選定当事者 - sentei tōjisha) under Article 30 of the Code of Civil Procedure, where one person is chosen to sue on behalf of a group. Japanese case law (notably a 1970 Supreme Court Grand Bench decision) has also recognized the possibility of consensual litigation standing even without a direct statutory provision, provided there is a rational necessity for it and it doesn't serve as a means to circumvent other legal principles, such as the general requirement for lawyer representation in certain courts or prohibitions against champerty (improperly funding and controlling litigation).

2. Plaintiff Standing for Condominium Management Associations:

The legal structure of a management association impacts its standing:

- Unincorporated Management Associations (権利能力なき社団 - kenri nōryoku naki shadan - "associations without legal personality"):

- These associations, though lacking full corporate personality, are recognized as having the capacity to be a party in a lawsuit (当事者能力 - tōjisha nōryoku).

- Substantively, rights that are considered to belong to the association (e.g., rights arising from contracts the association itself entered into) are, in strict legal theory, often treated as belonging collectively to all its members under a special form of co-ownership known as "sōyū" (総有).

- Despite this, Japanese case law has developed to allow such unincorporated associations to sue in their own name to enforce these collectively held rights. This is often conceptualized as a form of statutory litigation standing or, by some scholars, as a recognition of their "original" standing as the de facto right-holder for practical purposes. Such standing usually requires proof of proper internal authorization (e.g., a resolution from a members' meeting).

- Incorporated Management Associations (管理組合法人 - kanri kumiai hōjin):

- These associations are formally incorporated under the Condominium Ownership Act (建物の区分所有等に関する法律 - Tatemono no Kubun Shoyū tō ni Kansuru Hōritsu, hereinafter "COA") and possess full legal personality (法人格 - hōjinkaku).

- As legal persons, they can hold rights and incur obligations in their own name and, consequently, can sue to enforce their own rights (e.g., for unpaid management fees levied by and owed directly to the incorporated association).

- The COA also grants them specific authority to sue on behalf of unit owners in certain situations, typically requiring a resolution from a general meeting. Examples include initiating legal action against unit owners engaging in conduct detrimental to the condominium community (COA Article 57 et seq.) or pursuing matters that fall within their prescribed duties and are authorized by their bylaws or a resolution (COA Article 47, Paragraph 8). These are specific types of consensual litigation standing.

- For matters that fall outside their statutorily defined duties or generally accepted scope of operations, an incorporated association might still be able to act under the principles of ordinary consensual litigation standing, provided it receives specific authorization from the individual right-holders.

3. Positioning the Current Supreme Court Decision:

In the case of Condominium A and its incorporated association X, the key factors were:

- Nature of the Claims: The lawsuit concerned reimbursement claims. These were not debts originally owed to X or even to its predecessor, the Old Association. They were individual debts owed by Y to those specific unit owners who had advanced payments on Y's behalf.

- Timing of the Claims: The claims in question arose before X was incorporated.

- Basis of X's Standing (or lack thereof):

- X was not asserting that it was the original holder of these individual reimbursement rights.

- X was not (and likely could not successfully argue) that these individual reimbursement claims had somehow become collectively owned property of the Old Association for which X, as its successor, could now sue under the framework for unincorporated associations.

- Therefore, any potential standing for X would have to derive from some form of consensual litigation standing, meaning X would need to show it was authorized to pursue these specific, pre-existing, individual claims.

The High Court, affirmed by the Supreme Court, found no such authorization:

- There were no bylaws or resolutions of the Old Association explicitly granting it the power to sue for these individual reimbursement claims on behalf of the paying members.

- There was no evidence that X, after its incorporation, had received specific authorization from each of the individual unit owners (who held these reimbursement claims) to pursue these claims on their behalf.

4. Why the "Reimbursement" Nature is Critical:

The fact that these were not direct claims for unpaid management fees owed to an association but rather claims for reimbursement owed to specific individuals who voluntarily covered another's debt is a crucial distinction. These claims have a strong individual character.

While later amendments to the COA (e.g., Article 47, Paragraph 6, latter part, added by a 2002 revision) clarified that an incorporated management association's duties can include "claiming the return of unjust enrichment regarding common elements, etc.," this provision might not automatically cover pre-incorporation, individually-held reimbursement claims of the type seen in this case. Granting an association standing to sue for such highly individualized claims without the explicit consent of the individual right-holders could be problematic, as a judgment (even an unfavorable one) obtained by the association could then bind those individuals, potentially against their wishes or interests.

The Supreme Court's focus on the claims belonging to "each unit owner" and its finding that X was not "granted" the right to conduct litigation underscore the need for a clear grant of authority when an entity seeks to enforce rights that are fundamentally individual in nature.

5. General Consensual Litigation Standing Requirements:

Even if one were to argue for X's standing based on the general principles of consensual litigation standing (as per the 1970 Supreme Court precedent), X would have needed to demonstrate a "rational necessity" for it and that it wasn't a subterfuge. The current judgment didn't delve into these requirements, likely because the more fundamental issue – the absence of any clear evidence of authorization, whether general or specific under the COA – was dispositive.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's March 2001 decision serves as a clear reminder of the importance of establishing proper legal standing when initiating lawsuits, especially for collective entities like condominium management associations. The ruling highlights that:

- Reimbursement claims arising from individual unit owners voluntarily covering a delinquent owner's fees belong to those individual paying owners.

- An incorporated management association does not automatically acquire the right to sue for such pre-existing, individually-held reimbursement claims merely by virtue of its incorporation or its succession from an unincorporated predecessor.

- To pursue such claims, the incorporated association must demonstrate a clear basis for its authority to conduct litigation on behalf of the individual right-holders. This authority might come from specific provisions in its own (or its predecessor's) bylaws or resolutions that unequivocally cover such scenarios, or through explicit grants of authority from the individual unit owners who hold the claims.

In essence, when an association steps into court, particularly to enforce rights that did not originally accrue to it as an entity, it must be prepared to show "its papers" – the legal basis for its standing. This case underscores the need for careful drafting of association bylaws and, where necessary, obtaining specific authorizations to ensure that efforts to recover funds on behalf of members are legally sound.