Where is Home? Defining "Address" for Election Rights in Japan – The 1960 T Town Council Case

The concept of "address" or "domicile" is fundamental in many legal systems, serving as a crucial connecting factor for various rights and obligations, including taxation, civil litigation, and, significantly, political participation. In Japan, eligibility to vote and to stand for office in local elections is tied to having an "address" within the relevant electoral district. But in an increasingly mobile and complex society, how is this "address" determined when an individual's life spans multiple locations? A Japanese Supreme Court judgment on March 22, 1960, provided a clear, albeit challenging, standard for this determination in the context of election law.

The Concept of "Address" in Japanese Law

Before diving into the specifics of the case, it's helpful to understand the general legal framework for "address" (jūsho) in Japan:

- Civil Code Definition: Article 22 of the Japanese Civil Code defines a person's address as their "principal base of living" (生活の本拠 - seikatsu no honkyo). This definition emphasizes a substantive connection rather than mere formal registration.

- Determining Factors: Traditionally, identifying this "base of living" involves considering objective elements, such as the fact of actual, continuous residence, and subjective elements, like the individual's intent to make a place their permanent home. Legal scholarship in Japan has debated the relative weight of these factors, with the "objective theory" – which assesses the center of one's life based on objective facts, including expressed intent as one of those facts – generally prevailing over a purely "subjective theory" that would prioritize intent alone.

- Single vs. Multiple Addresses: A significant theoretical debate, particularly relevant after World War II with the increasing complexity of modern life, concerns whether a person can have only one "address" (the "single address theory," jūsho tan'itsu setsu) or multiple "addresses" corresponding to different spheres of life, such as a private life address, a business address, etc. (the "multiple addresses theory" or "life-relation-standard theory," jūsho fukusū setsu). The latter gained considerable traction among legal scholars in Japan.

- Legal Significance: The determination of "address" has wide-ranging legal consequences, impacting areas such as the place for performance of obligations in contracts, jurisdiction in legal proceedings, inheritance matters, tax obligations, and, as in this case, electoral rights under the Public Offices Election Act (Kōshoku Senkyo Hō) and rights as a resident under the Local Autonomy Act (Chihō Jichi Hō).

The Factual Background: A Disputed Council Member's Eligibility

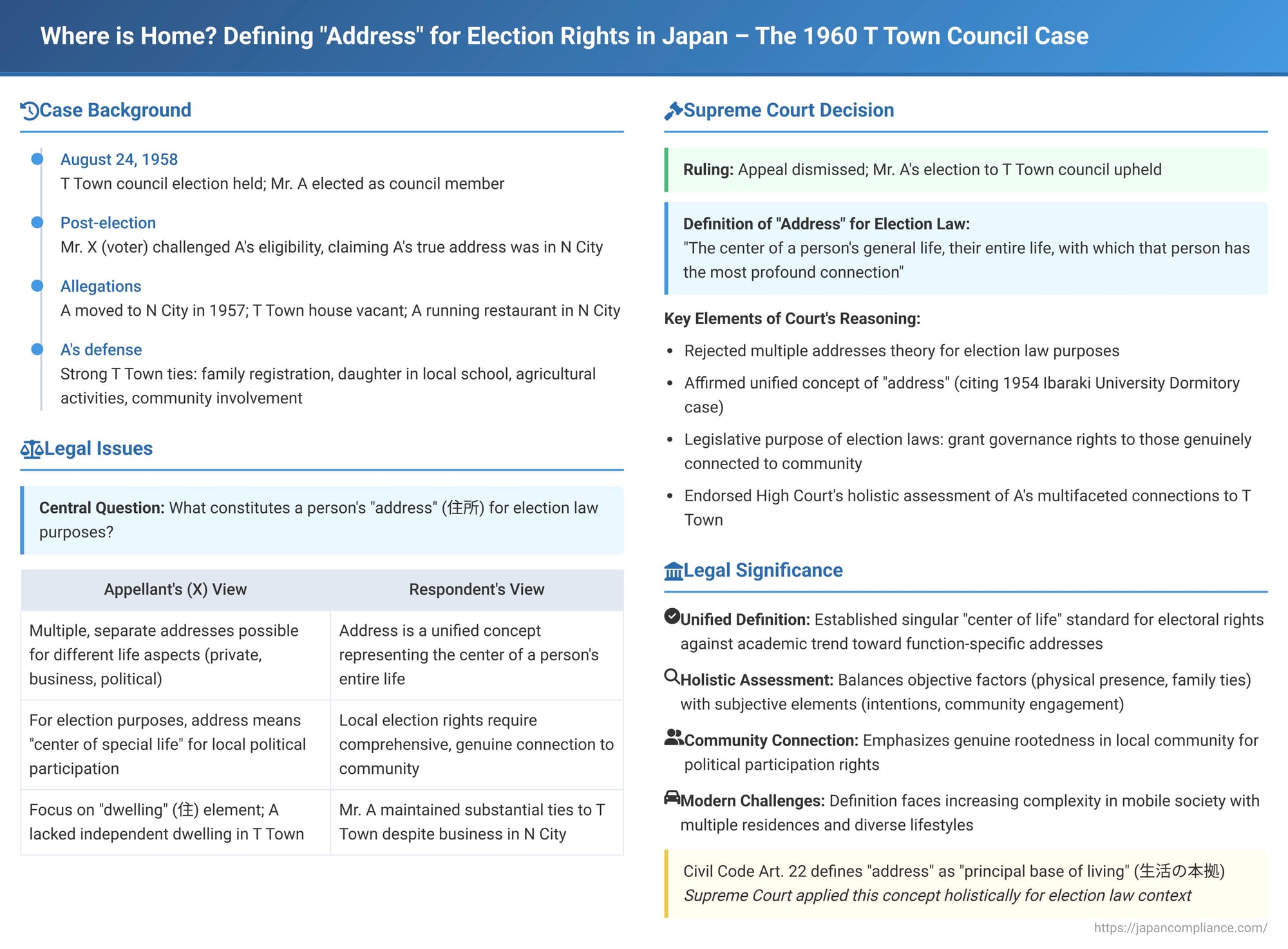

The case arose from a general election for the town council of T Town, Shiga Prefecture, held on August 24, 1958.

- The Challenge: Mr. X, a registered voter in T Town, challenged the validity of the election of Mr. A to the town council. X argued that Mr. A was ineligible to be elected in T Town because his true address at the time of the election was not in T Town but in the nearby N City.

- Allegations Against Mr. A's T Town Address:

- X asserted that around September 1957, Mr. A had moved his primary residence to N City, where he was actively engaged in operating a restaurant and a finance business.

- According to X, Mr. A's house in T Town had been vacant since that time, and even the electricity supply to it had been discontinued.

- While Mr. A owned a small amount of agricultural land in T Town, X claimed this was insufficient to provide a livelihood and was not A's primary occupation.

- Lower Court Proceedings: Mr. X's initial objections were dismissed by the T Town Election Administration Commission and subsequently by the Shiga Prefectural Election Administration Commission (Y, the defendant in the lawsuit). X then brought the case before the Osaka High Court.

- The Osaka High Court's Findings: The High Court, after examining various aspects of Mr. A's life, concluded that his legal address remained in T Town. The factors influencing the High Court's decision included:

- Mr. A's stated preference not to become a full-fledged resident of N City and his deliberate limitation of social interactions in N City to those strictly necessary for his business operations there.

- Although Mr. A's house in T Town was indeed vacant, he maintained the family's Buddhist altar there and kept agricultural tools and various household belongings on the premises.

- Mr. A and his family's official resident registration (jūminseki) was maintained with his father in T Town. Significantly, Mr. A's eldest daughter resided with A's father in T Town and attended the local elementary school there.

- Mr. A continued to cultivate both his own and his father's agricultural fields located in T Town.

- He remained actively involved in the T Town community, holding various official positions in local organizations and conducting these social activities while staying at his father's house in T Town.

Based on these multifaceted connections, the Osaka High Court dismissed X's claim.

The Appellant's (X's) Argument to the Supreme Court

Mr. X appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court, presenting a nuanced legal argument for how "address" should be interpreted in the context of election law:

- Rejection of "Base of All Life": X argued that the term "address" as used in Article 9, Paragraph 2 of the Public Offices Election Act should not be simplistically interpreted as the "base of all life".

- Multiple Centers of Life: He contended that in an increasingly complex modern society, individuals often have distinct centers for different aspects of their lives – for example, a center for their private life, another for their business or professional activities, and potentially another for their ideological or political engagements. X proposed that the law should recognize these separate centers when regulating different legal relationships.

- "Address" for Election Purposes: Specifically for election law, X suggested that "address" should be understood as the "center of the special life" pertaining to the act of voting for, or being elected as, a local council member. This "special life," he argued, is intrinsically linked to the rights and responsibilities of being a "resident" of a local public entity, as defined in Articles 10 and 11 of the Local Autonomy Act.

- Focus on "Dwelling": X further posited that this concept of resident life, particularly in the context of local autonomy, aligns closely with the "dwelling" aspect (住 - jū) of the traditional three main elements of private life (clothing, food, and shelter – 衣食住, ishokujū). He claimed that Mr. A's true base of living was in N City and that A merely used his father's address in T Town for convenience, lacking an independent dwelling of his own in T Town.

The Supreme Court's Decision: A Unified Concept of "Address" for Elections

The Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court, in its judgment of March 22, 1960, unequivocally rejected Mr. X's arguments and dismissed the appeal.

- Rejection of Multiple Addresses Theory for Election Law: The Supreme Court explicitly disagreed with the appellant's proposition that "address" for election law purposes could be fragmented into separate spheres for private life, business activities, and political activities.

- The "Center of General, Entire Life" Standard: The Court reaffirmed its established interpretation, citing its own earlier Grand Bench decision from October 20, 1954 (often referred to as the Ibaraki University Seirei Dormitory case). According to this interpretation, "address" as a requirement for suffrage under both the Public Offices Election Act and the Local Autonomy Act is to be understood as "the center of a person's general life, their entire life, with which that person has the most profound connection."

- Purpose-Driven Rationale: The Court explained that this holistic interpretation is rooted in the legislative purpose of these acts: to grant the right to participate in the governance of a local public entity to those individuals who have established a genuine, comprehensive, and deeply rooted connection to that community through their presence there for a specified period.

- Affirmation of the Lower Court's Factual Assessment: The Supreme Court found that the Osaka High Court had correctly applied this unified concept of "address" when it meticulously considered the various facts of Mr. A's life and activities across both T Town and N City. The Supreme Court endorsed the High Court's conclusion that, based on this holistic assessment, Mr. A's legal address had not, in fact, relocated from T Town to N City.

Consequently, Mr. X's appeal was dismissed, and Mr. A's election to the T Town council was upheld.

Analysis and Implications

The Supreme Court's 1960 ruling in this case has several important implications for the understanding of "address" in Japanese election law:

- Solidification of a Unified Definition for Suffrage: The decision firmly established a unified and holistic definition of "address" for the purpose of electoral rights, resisting the academic trend towards recognizing multiple, function-specific addresses. For political participation in a local community, the Court prioritized a comprehensive and singular "center of life" within that community.

- Holistic Assessment Balancing Objective and Subjective Factors: While the Civil Code's definition of address as the "base of living" points towards an objective standard, the practical application by the courts, as seen in the High Court's detailed examination in this case (and endorsed by the Supreme Court), involves a broad assessment of numerous factors. These include not only physical presence and dwelling arrangements but also family ties, social engagements, community involvement, economic activities, and, significantly, the individual's expressed intentions and conduct regarding their connections to different locales. The legal commentary accompanying the case notes the High Court's emphasis on these "intentional elements" in Mr. A's situation, alongside objective ties to T Town.

- Challenges in a Modern, Mobile Society: Defining a single "center of entire life" can present considerable practical challenges in contemporary society, characterized by increased personal and professional mobility, the prevalence of multiple residences for work or leisure, and diverse family structures and lifestyles. The legal commentary touches upon the inherent difficulty and potential unfairness of unilaterally imposing a specific "standard" lifestyle as the benchmark for determining an address, especially when such a determination can lead to severe consequences like disenfranchisement or the loss of an elected position. It is noted that more recent lower court decisions have shown caution in negating an address based solely on limited utility usage at one location when other significant ties to that community exist.

- Debate over the Civil Code's General "Address" Definition: The commentary references the noted legal scholar Professor Kawashima Takeyoshi's critique of the Civil Code's very general definition of "address" in Article 22. Prof. Kawashima argued that such a broad, one-size-fits-all definition is almost "technically useless" because different legal fields (e.g., contract law, family law, tax law, election law) might inherently require different nuances and policy considerations in defining a relevant connecting factor like "address". However, the commentary also suggests, perhaps paradoxically, that the very generality of the "base of living" concept has allowed courts the flexibility to interpret "address" in a manner that aligns with the specific spirit and purpose of the laws in each distinct field, as was done here for election law.

- Consistency in Subsequent Election Law Jurisprudence: The Supreme Court has generally maintained this holistic and unified interpretation of "address" in subsequent election law cases, for example, when dealing with allegations of sham address registrations made solely to gain an unfair electoral advantage.

Conclusion

The Japanese Supreme Court's 1960 decision in the T Town council case remains a significant and foundational ruling for understanding the legal concept of "address" within the specific context of Japanese election law. It champions a holistic approach, requiring an assessment of an individual's entire life to pinpoint their primary center of living and connection to a community, rather than allowing for a fragmented understanding of address based on different life functions.

While this standard provides a clear legal directive, its application in an increasingly complex and mobile world continues to demand careful, fact-intensive judicial scrutiny. Courts must balance objective indicators of residence with evidence of an individual's genuine, multifaceted ties and commitments to a particular local community when determining electoral rights and eligibility. This ruling underscores the idea that for participation in local governance, more than a superficial or transient connection is required; a deep and general rootedness in the life of the community is paramount.