When Your Alias Isn't You: Japan's Landmark Ruling on Identity and Forgery

In many spheres of life, a person's name is what they are known by. An author's pen name or an actor's stage name can become so famous that it effectively replaces their legal identity in the public consciousness. In principle, using such an alias to sign a document is not the crime of forgery, because there is no deception; the name, though not the legal one, clearly points to the person using it. But what happens when the document is not a manuscript or an autograph, but an official application to a government agency? Does the formal nature of the document change the legal meaning of one's identity?

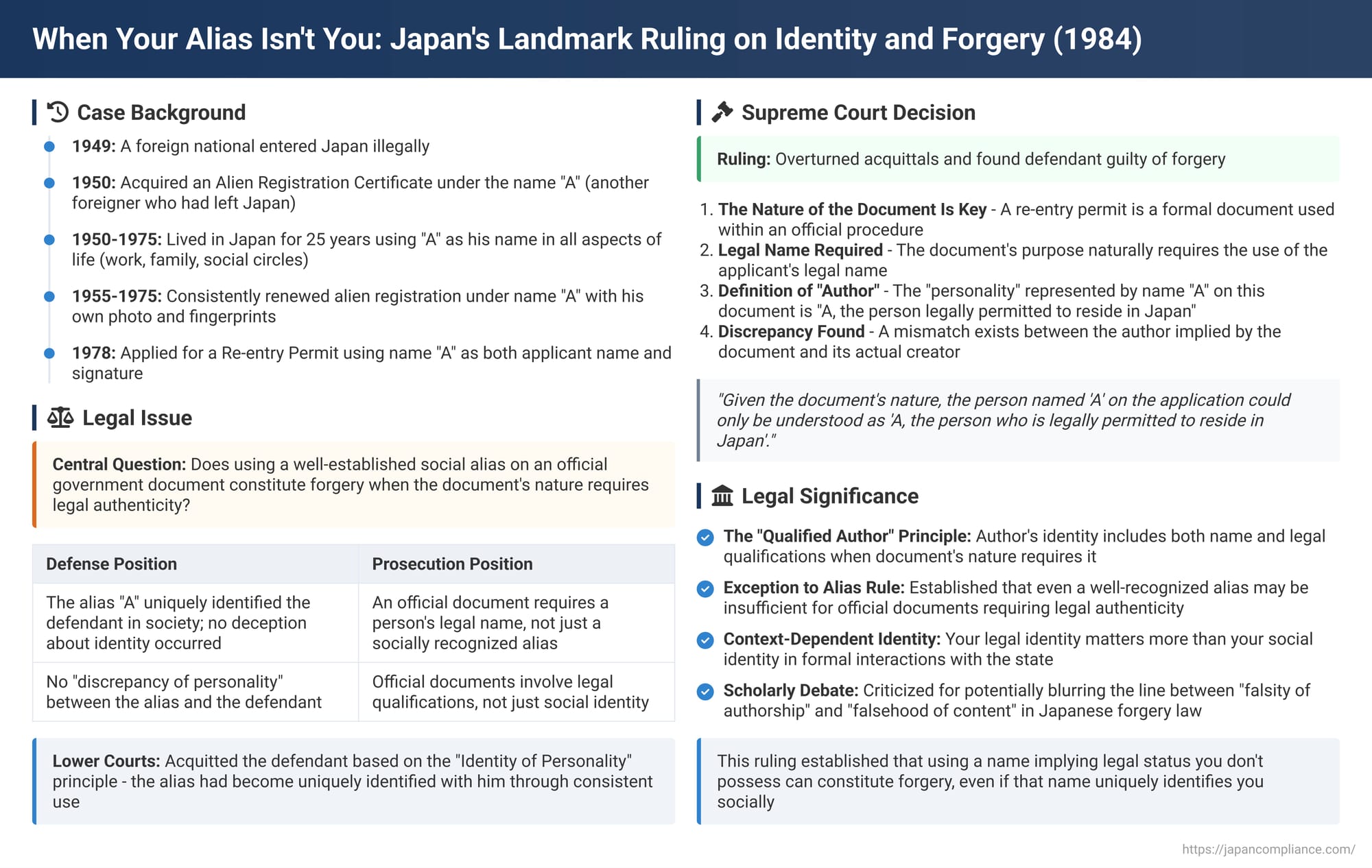

This profound question was at the center of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on February 17, 1984. In a case involving a foreign national who had lived under an alias for decades, the Court delivered a nuanced and powerful ruling, establishing that even a universally recognized alias may not be enough to shield its user from a forgery conviction when the document's nature demands legal, not just social, authenticity.

The Facts: A Life Lived Under an Alias

The defendant's story was a long and complex one.

- He was a foreign national who had entered Japan illegally around 1949.

- In 1950, he acquired an Alien Registration Certificate under the name "A". This name belonged to another real foreigner who had already left Japan. The certificate, however, bore the defendant's own photograph.

- For the next 25 years, the defendant lived his life in Japan using "A" as his name. He used it in all aspects of his public and private life, including with his family, friends, and in his work as a journalist and member of the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan (Chongryon).

- He consistently renewed his alien registration under the name "A," each time submitting his own photograph and, from 1955 onwards, his own fingerprints.

- As a result, the alias "A" became so socially established that it uniquely identified the defendant, and there was no risk of confusion with anyone else. Only a small number of relatives and people from his hometown knew his original legal name.

- In 1978, wishing to travel abroad, the defendant filled out an official "Application for Re-entry Permit" addressed to the Minister of Justice. On the form, in both the name field and the applicant signature line, he wrote "A" and affixed a personal seal carved with the name "A".

The Lower Courts' Verdict: "A" is "A"

The defendant was charged with Forgery of a Private Document with Signature and Seal. The lower courts, however, acquitted him of this charge.

- The "Identity of Personality" Principle: The courts based their decision on the core principle of forgery law, which holds that the essence of the crime is to falsify the "identity of personality" between the author of a document and the person named in it.

- No Discrepancy Found: They reasoned that because the alias "A" had, through decades of consistent use, come to uniquely signify the defendant in society, there was no discrepancy. The author (the defendant) and the named person ("A") were, for all practical purposes, the same person. They concluded that no deception about identity had occurred, and therefore, no forgery was committed. The prosecutor appealed.

The Supreme Court's Reversal: The Legal Persona vs. The Social Persona

The Supreme Court overturned the acquittals and found the defendant guilty of forgery. The Court agreed with the basic "identity of personality" principle but introduced a critical new layer to the analysis: the nature of the document itself.

The Court's sophisticated reasoning proceeded in several steps:

- The Nature of the Document is Key: The Court emphasized that one cannot determine identity in a vacuum. The specific type of document is paramount. A re-entry permit application is not a casual letter; it is a formal document used within a public, official procedure.

- A "Legal Name" is Required: The very purpose of a re-entry permit is to allow a foreigner legally residing in Japan to travel and return. Its issuance is premised on the applicant having a lawful status of residence. Therefore, the Court reasoned, confirming the applicant's legal status and qualifications is essential to the screening process. The nature of this document "naturally requires" that it be created using the applicant's legal name (honmyō).

- Defining the "Author" on the Document: The Court then defined the "personality" represented by the name "A" on this specific document. It was not the socially known individual. Given the document's nature, the person named "A" on the application could only be understood as "A, the person who is legally permitted to reside in Japan.".

- A "Discrepancy of Personality" Exists: The defendant, as a person who had entered the country illegally and possessed no lawful status of residence, was fundamentally not the person described above. Even though he was socially known as "A," he was not the "A" with legal residence status. The Court found that he had, for years, been "impersonating" the legally registered "A" through the fraudulent alien registration system. Therefore, a "discrepancy in the identity of personality" clearly existed between the author implied by the document (a legal resident) and the actual creator of the document (a non-legal resident). This discrepancy is the essence of forgery.

Analysis: A Contentious Blurring of Legal Lines?

This ruling is a landmark because it established that for certain official documents, "identity" is not merely a matter of social recognition but includes the legal qualifications required to be the document's author.

- The "Qualified Author" Principle: The decision is a prime example of a legal logic where the author of a document is defined not just by their name, but by their name plus a specific, necessary qualification. The author of the re-entry permit application was not just anyone named "A," but "A, the legal resident." Since the defendant lacked this qualification, he could not be that person. This same logic has been applied in other cases, such as those involving individuals impersonating licensed lawyers.

- A Theoretical Critique: This approach has been heavily debated by legal scholars. A primary criticism is that it appears to punish a "falsehood of content" (mukei gizō)—the lie about one's legal status—under the guise of "falsity of authorship" (yūkei gizō), which is the crime of tangible forgery. The defendant's true deception was about his legal right to be in Japan. By defining the "author" as "A, the legal resident," the Court effectively incorporated the substantive question of legal status into the formal question of identity, thereby blurring the line between two distinct types of forgery crimes in Japanese law.

Conclusion

The 1984 Supreme Court decision carves out a major exception to the general rule that using a well-established alias is not forgery. It sets forth the crucial principle that when a document's nature and purpose—particularly in formal interactions with the state—inherently require the verification of legal status or qualifications, the author's identity is defined not just by their socially recognized name but by that name plus the necessary legal attributes. The case serves as a powerful lesson: in the eyes of the law, your identity is not always just who people think you are, but who you are legally authorized to be. Using a name that implies a legal status you do not possess can cross the line from a simple alias into the serious crime of forgery.