When Trust Is Not Enough: A Landmark Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on a Supervisor's Duty of Care

Case: Judgment of the Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, November 15, 2005.

Subject: Professional Negligence Resulting in Death

Introduction

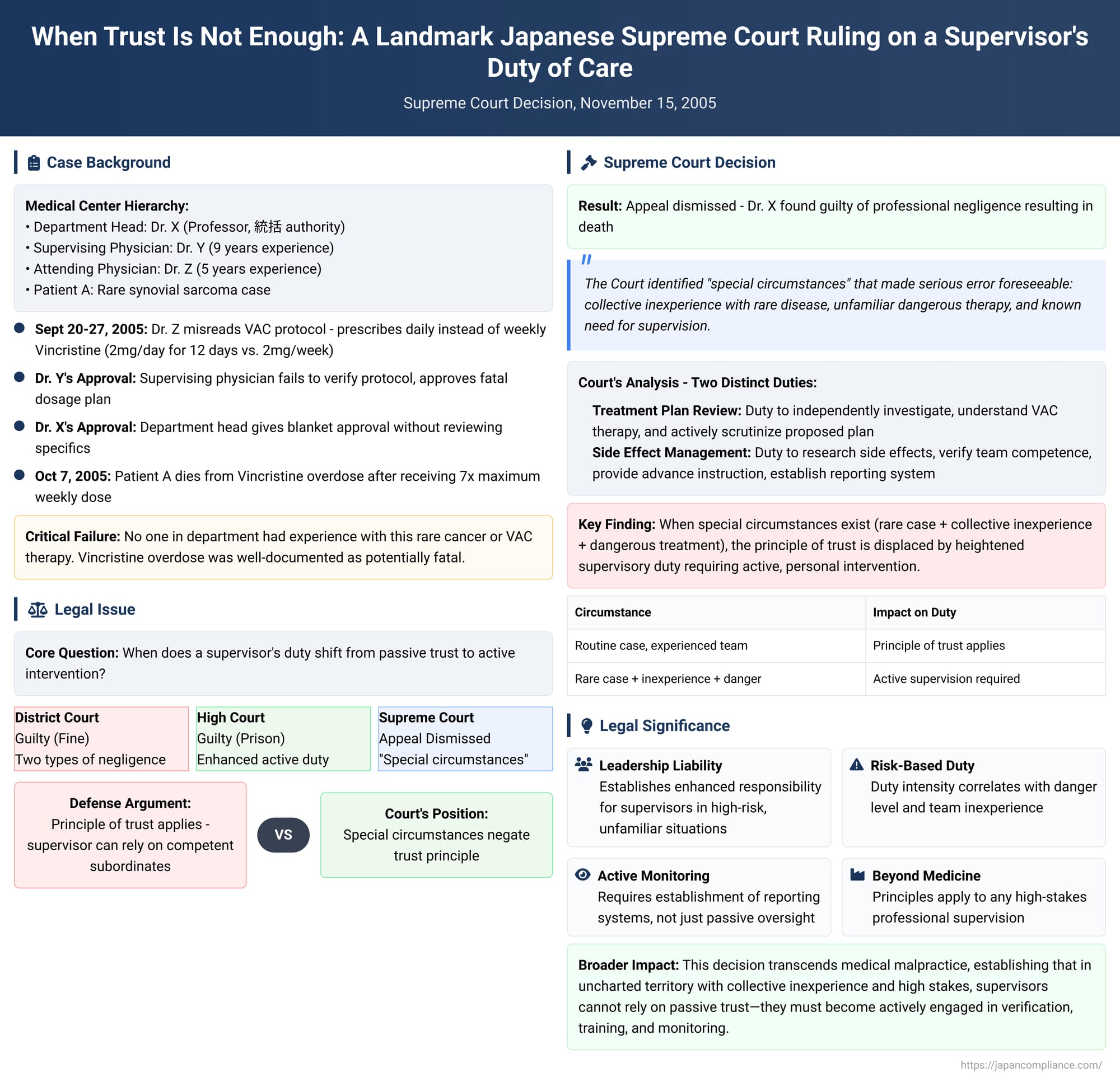

On November 15, 2005, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark decision that meticulously explored the boundaries of professional liability, particularly the responsibility of a high-level supervisor for the fatal errors of a subordinate team. This case of medical malpractice, arising from a tragic series of missteps at a major medical center, serves as a powerful illustration of how the "principle of trust"—the idea that one professional can reasonably rely on the competence of another—can be negated under specific, high-risk circumstances. The Court’s detailed reasoning provides a crucial framework for understanding when a supervisor's duty shifts from passive oversight to active, personal intervention. For leaders and managers in any high-stakes field, the principles elucidated in this decision are of profound importance, highlighting the enhanced legal and ethical duties that arise when navigating unfamiliar and dangerous territory.

A Cascade of Errors: The Factual Background

The case centered on the treatment of a patient, A, who was diagnosed with synovial sarcoma in her submandibular region. This form of cancer was not only aggressive and had a poor prognosis, but it was also extremely rare in this part of the body. Crucially, no physician in the Otolaryngology (Ear, Nose, and Throat) department at the medical center, from the most junior resident to the department head, had any clinical experience with this specific disease.

The medical center's protocol for patient care involved a team-based approach. For patient A, a team was formed consisting of an attending physician, Z; a supervising physician, Y; and a resident. Dr. Z, who had been a licensed physician for five years, was the primary doctor responsible for the patient's care. Dr. Y, with nine years of experience and certified as a specialist, was tasked with guiding Dr. Z. Both were under the ultimate authority of the defendant, Dr. X, the distinguished professor and head of the ENT department. As department head, Dr. X was responsible for統括 (tōkatsu) — a Japanese term implying comprehensive oversight and final decision-making authority for all medical activities within his department.

The treatment team, lacking a standard protocol for this rare cancer, sought potential therapies. Dr. Z was advised by a colleague that VAC therapy, a chemotherapy regimen effective against other types of sarcomas, might be beneficial. VAC therapy involves a combination of three drugs, one of which is Vincristine sulfate. Vincristine is a potent and well-known cytotoxic agent. Medical literature and the drug's own documentation are replete with warnings about its severe toxicity, especially nerve damage and bone marrow suppression. The literature unequivocally states that an overdose can be fatal, and numerous medical error reports had been published regarding exactly such outcomes. The standard dosage protocol for adults is a maximum single dose of 2mg administered intravenously once per week.

Here, the first critical error occurred. Dr. Z went to the medical center’s library to research the VAC protocol. He found a treatment plan in a medical journal but made a catastrophic misreading: he overlooked the word "week" and misinterpreted the dosage schedule as requiring a daily administration. He concluded that the protocol called for administering 2mg of Vincristine every day for 12 consecutive days.

This flawed understanding initiated a complete breakdown in the hospital's chain of command and safety checks.

- Flawed Plan and First-Level Approval: Dr. Z presented his daily-dose plan to his direct supervisor, Dr. Y. Dr. Y, despite being the designated "supervising physician," failed to conduct his own due diligence. He did not consult the medical literature or the drug's package insert. He, too, glanced at the protocol copy provided by Dr. Z and failed to notice the "week" versus "day" discrepancy. He approved the fatally flawed plan.

- Second-Level, Non-Specific Approval: Following Dr. Y's approval, Dr. Z sought final clearance from the department head, Dr. X. Dr. Z reported only that he intended to use VAC therapy for patient A. Dr. X, despite having no experience with this therapy himself, gave his approval without asking for any specifics. He did not inquire about the dosage, the administration schedule, potential side effects, or the team's plan for managing them. He essentially greenlit a concept without examining its execution.

- Tragic Implementation: On September 27, the daily administration of 2mg of Vincristine began. The following day, a departmental conference was held. Dr. Z again reported that patient A was receiving VAC therapy, and Dr. X again gave his assent without reviewing the specific treatment chart or asking for details.

The patient’s condition deteriorated rapidly and predictably. Within days, she began to exhibit classic signs of severe Vincristine toxicity: debilitating fatigue, numbness in her extremities, intense pain, high fever, and oral sores. By October 3, seven days into the regimen—having received seven times the maximum weekly dose—her blood tests showed a catastrophic drop in platelets, and she had visible hemorrhaging. Dr. Z, alarmed by the symptoms, finally ordered a temporary halt to the Vincristine administration.

Dr. X saw the patient in a wheelchair around this time and noted her weakened state, attributing it generally to the side effects of chemotherapy. On October 4, he saw her again and recognized she was in critical condition, but the thought of a massive overdose did not occur to him, and he gave no specific instructions to the team.

It was not until the evening of October 6 that Dr. Y and Dr. Z, along with another colleague, finally re-examined the original protocol and discovered the horrifying "week" versus "day" error. Their realization came too late. On October 7, patient A died of multiple organ failure caused by the Vincristine overdose.

Subsequent expert testimony from the head of the hospital's emergency center suggested that had the overdose been identified and aggressive treatment started by October 1 (after the fifth dose), the patient's life could have been saved with confidence.

The Legal Journey: From Lower Courts to the Supreme Court

The case proceeded through the Japanese court system, with each level refining the legal analysis of Dr. X’s culpability as the supervisor.

- The District Court (First Instance): Found Dr. X guilty and imposed a fine. It identified two distinct types of negligence:

- Negligence in carelessly approving the erroneous treatment plan.

- Negligence in failing to properly instruct the attending physician, Dr. Z, in advance on how to manage the drug's known side effects.

- The High Court (Second Instance): Both the prosecution and Dr. X appealed. The High Court upheld the first finding of negligence (approving the plan). However, it found the District Court’s reasoning on the second point to be a mischaracterization of the facts. The High Court went further, imposing a more direct and active duty on Dr. X. It ruled that he had a duty to "accurately grasp the patient's treatment status and the manifestation of side effects... and if severe side effects appeared, to promptly implement appropriate countermeasures to prevent a fatal outcome." Finding this more serious breach of duty, the High Court overturned the fine and sentenced Dr. X to a one-year prison term with a three-year suspension. Dr. X then appealed to the final arbiter, the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Analysis: Foreseeability in Special Circumstances

The Supreme Court upheld the High Court’s conviction, dismissing Dr. X's appeal. Its written decision provides a masterclass in the application of negligence principles, focusing on the concepts of foreseeability and the duty of care in the context of supervision. The court systematically broke down Dr. X's negligence into two key areas.

1. Negligence in the Approval of the Treatment Plan

The Court's central logic rested on the existence of a unique constellation of "special circumstances" that made a serious error by the treatment team foreseeable. These circumstances were:

- Extreme Rarity: The patient's synovial sarcoma in the head and neck region was an exceptionally rare case.

- Collective Inexperience with the Disease: No one in the department, from the junior doctors to Dr. X himself, had any clinical experience treating this specific condition.

- Collective Inexperience with the Treatment: Similarly, no one in the department, including Dr. X, had ever administered VAC therapy.

- Inherent Danger of the Drug: The primary drug, Vincristine, was known to be highly toxic, with a well-documented risk of fatal outcomes from overdose.

- Recognized Need for Supervision: Dr. X himself had acknowledged that the physicians in his department required careful guidance and supervision to prevent errors.

The Court reasoned that, taken together, these factors fundamentally altered the supervisor's role. In a routine case involving an experienced team, a department head might be justified in trusting his subordinates to execute their tasks correctly (the "principle of trust"). However, in this specific situation, the confluence of risks made it objectively foreseeable that the inexperienced team, grappling with an unfamiliar disease and a dangerous, unfamiliar therapy, could make a critical error in formulating the treatment plan.

Because such an error was foreseeable, the principle of trust was displaced. A heightened duty of care was therefore imposed upon Dr. X. The Court concluded that Dr. X had a positive and personal duty to:

- Independently investigate the clinical literature, drug package inserts, and other relevant sources.

- Gain a sufficient understanding of VAC therapy, including its proper application, dosage, and side effects.

- Actively and concretely review the specifics of the proposed treatment plan.

- Scrutinize the plan for errors and, if any were found, to correct them.

Dr. X's failure to take any of these steps—instead giving a blanket, non-specific approval—was a clear breach of this heightened duty. He had ample opportunity, the court noted, between the initial proposal around September 20 and the departmental conference on September 28, to demand the details of the plan and perform this necessary verification. His passivity was, in the eyes of the law, negligence.

2. Negligence in the Management of Side Effects

The Court then applied the same "special circumstances" logic to the events that unfolded after the treatment began. It was just as foreseeable that an inexperienced team might fail to correctly identify, interpret, and respond to the drug's severe side effects. This foreseeability gave rise to a second, distinct duty of care related to monitoring and response.

The Supreme Court articulated this duty as a multi-part supervisory responsibility. Dr. X was obligated to:

- Conduct Personal Research: He had a duty to research and understand the potential side effects of Vincristine and the appropriate medical responses to them.

- Verify Team Competence: He was required to confirm his subordinates' knowledge of these side effects and their management.

- Provide Advance Instruction: He had a duty to provide proactive guidance and training to the team on how to manage the side effects effectively before treatment began.

- Establish a Reporting System: Crucially, he had a duty to issue specific instructions for the team to report to him immediately if any concerning side effects manifested.

The Court determined that Dr. X’s failure to fulfill this duty was a direct cause of the patient's death. It pointed to the expert testimony, concluding that if Dr. X had established this proper supervisory framework, he would have been informed of the severe adverse reactions by October 1 at the latest. At that stage, a proper intervention could have been made, and the patient’s life would have been saved.

Significantly, the Supreme Court also refined the High Court's reasoning on this point. It agreed that imposing a duty on Dr. X to monitor the patient with the exact same diligence as the attending physician would be an excessive burden for a department head. However, it interpreted the High Court’s ruling not as a duty of direct, moment-to-moment patient care, but as a duty to establish the supervisory system itself—the training, the instructions, and the reporting channels. The negligence lay in the failure to create this safety net, which would have enabled him to grasp the situation through reports from his team and intervene when necessary.

Conclusion: The Boundaries of Supervisory Liability

The 2005 Supreme Court decision is a seminal case in Japanese law on professional responsibility. It establishes that while supervisors are not automatically liable for every mistake made by their subordinates, their liability is significantly magnified in situations of high risk, high uncertainty, and collective inexperience.

The ruling does not create an unlimited scope of liability. Its power lies in its detailed, fact-dependent analysis. The "special circumstances" are the linchpin; they define the threshold at which the passive "principle of trust" dissolves and an active, personal duty of care materializes. In more routine circumstances, with experienced staff performing familiar tasks, a supervisor's reliance on their team would likely still be deemed reasonable.

This case serves as a critical lesson in risk management that transcends the medical field. It teaches that when an organization ventures into uncharted territory—whether it be a rare medical case, a novel engineering project, or a high-stakes financial transaction—the responsibilities of senior leadership intensify. Passive oversight is insufficient. Leaders have a duty to become actively engaged: to understand the specific risks involved, to independently verify critical plans, and to ensure that robust systems for monitoring and reporting are not just in place, but are effectively and explicitly communicated. This decision from Japan's highest court stands as a stark reminder that in the face of foreseeable danger, trust is not a strategy; it is a privilege that must be earned through rigorous and active supervision.