When Trust Erodes: A Guarantor's Right to Exit an Endless Guarantee in Japan (A 1964 Landmark)

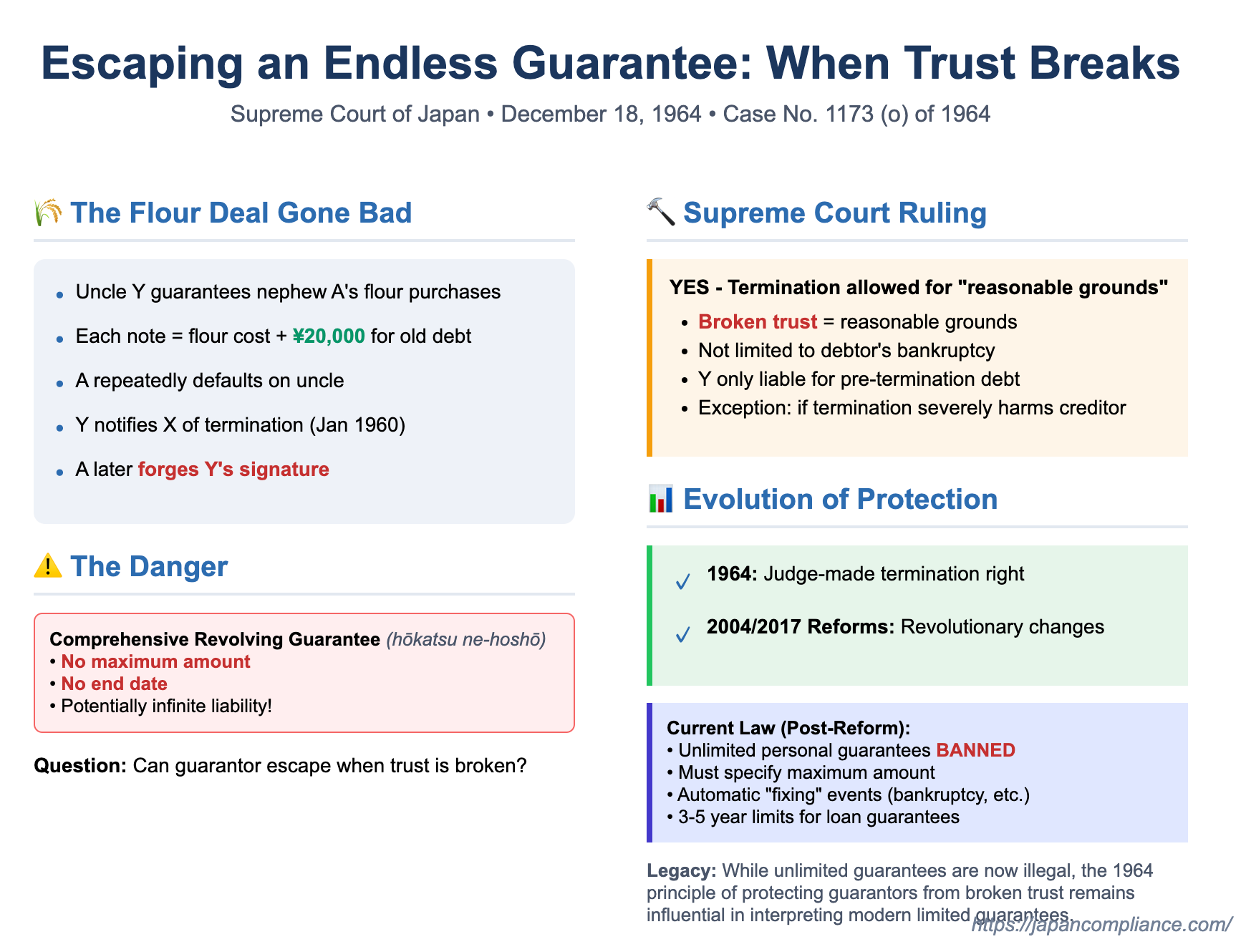

Imagine guaranteeing someone's future debts without any clear end date or a cap on the amount. This is the nature of a "comprehensive revolving guarantee" (hōkatsu ne-hoshō), a type of surety that, while offering flexibility in ongoing business transactions, can expose the guarantor to potentially limitless and indefinite liability. A pivotal Japanese Supreme Court decision on December 18, 1964 (Showa 38 (O) No. 1173), addressed a critical question: can a guarantor unilaterally cancel such an open-ended commitment, especially when their trust in the person they guaranteed has been broken? This judgment became a cornerstone in the judicial efforts to protect guarantors before later comprehensive Civil Code reforms.

What is a Revolving Guarantee (Ne-Hoshō)?

A revolving guarantee is distinct from a guarantee for a single, specific debt. It covers a series of unspecified debts that may arise in the future from a continuous relationship between a creditor and a principal debtor (e.g., ongoing supply contracts, running credit accounts). A "comprehensive" revolving guarantee is particularly precarious for the guarantor as it traditionally had no pre-set maximum limit on the amount guaranteed (kyokudogaku) and no fixed termination date. This meant the guarantor's potential liability could escalate unexpectedly over an undefined period.

Facts of the 1964 Case: An Uncle's Guarantee and a Nephew's Defaults

The 1964 case painted a classic scenario of such a guarantee going awry:

- The Parties: X was a flour wholesaler (the creditor). A was another flour wholesaler who purchased from X (the principal debtor). Y was A's uncle (the guarantor).

- The Guarantee: Previously, X had suspended business with A due to A's substantial unpaid debts. Transactions resumed after Y stepped in and offered a guarantee around autumn 1959. Under this arrangement, for each new purchase A made from X, Y would issue a promissory note to X covering the cost of the new flour plus an additional 20,000 yen to pay down A's pre-existing debt. This guarantee provided by Y had no specified duration and no monetary cap—it was a comprehensive revolving guarantee.

- Breakdown of Trust: A had an internal agreement with his uncle Y to remit payments for the flour by the 5th of each following month. However, A repeatedly failed to do so. This forced Y to cover A's defaults out of his own pocket, and Y's financial exposure grew considerably.

- Y's Attempt to Terminate: Due to A's repeated failures and the mounting financial burden, Y, around January 1960, informed X (the creditor) of his decision to terminate the guarantee contract for future transactions.

- A's Deception and X's Lawsuit: Despite Y's notification to X, A later deceived X by falsely claiming he still had Y's backing for further transactions. A then forged Y's signature on new promissory notes and gave them to X. When these forged notes went unpaid, X sued Y, primarily for payment on the notes, and alternatively, for performance of the original guarantee obligation.

- Lower Court Ruling: The appellate court found that the notes X received after Y's termination notice were indeed forgeries and dismissed X's claim on them. Crucially, for the alternative claim on the guarantee, the court recognized Y's termination of the guarantee as valid. It held Y liable only for the portion of A's debt that had accrued before Y validly terminated the guarantee (a sum of 14,100 yen out of a total unpaid amount of 194,100 yen).

X appealed to the Supreme Court, specifically challenging the lower court's ruling that Y's termination of the open-ended guarantee was effective.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Upholding the Guarantor's Right to Terminate

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, affirming the lower court's decision and thereby solidifying a guarantor's right to terminate a comprehensive revolving guarantee under certain conditions.

Key Principle: Termination for "Reasonable Grounds"

The Court held that a continuous guarantee contract without a fixed term, like the one Y provided, can be unilaterally terminated by the guarantor if there are "reasonable grounds" for doing so.

- What Constitutes "Reasonable Grounds"? The Court specifically included situations where the guarantor's trust relationship with the principal debtor has been impaired. Y's situation—where A repeatedly breached his payment promises to Y, causing Y direct financial loss and undermining Y's confidence in A's reliability—was deemed a valid reason. The Court indicated that "reasonable grounds" were not strictly limited to a drastic worsening of the principal debtor's overall financial condition.

- Exception – Overriding Harm to Creditor: The right to terminate is not absolute. Termination might be denied if it would cause the creditor "damage that cannot be overlooked in light of the principle of good faith" (i.e., if there were special circumstances making the termination exceptionally unfair to the creditor). However, no such special circumstances were found to exist for X in this case.

Clarification of Prior Case Law:

X had argued that earlier Daishin-in precedents meant an open-ended guarantee could only be terminated if a "substantial period has passed" or if "the debtor's financial condition has significantly worsened." The Supreme Court clarified that while a significant deterioration in the debtor's finances could justify termination even before a substantial period had elapsed (as an unforeseen special circumstance), termination was also permissible after a "substantial period" for other reasonable grounds, such as the impaired trust seen in Y's case. The Court found that Y's termination request was made after a sufficient period had passed anyway.

The Evolution of Guarantor Protection: From Judge-Made Law to Civil Code Reforms

This 1964 judgment was a significant development in judge-made law aimed at protecting guarantors from the potentially endless and boundless risks of comprehensive revolving guarantees.

- Early Case Law Foundations: Prior to this, the Daishin-in had already begun to carve out termination rights for guarantors in such situations, often invoking principles of "good faith" or citing a substantial decline in the principal debtor's financial health as grounds for termination. The 1964 case expanded these grounds by explicitly recognizing the impairment of the trust relationship between the guarantor and the principal debtor. Legal commentators distinguished between an "ordinary termination right" (arising after a considerable time, possibly with a notice period) and a "special termination right" (allowing immediate termination for specific serious causes). The 1964 ruling affirmed a type of special termination right based on impaired trust.

- The 2004 and 2017 Civil Code Reforms – A New Landscape:

The Japanese Civil Code has since undergone significant reforms regarding guarantees, particularly personal revolving guarantees:- Ban on Unlimited Personal Revolving Guarantees: The most crucial change is that comprehensive revolving guarantees (those without a pre-set maximum limit on the guaranteed amount) are now prohibited for all personal guarantors (guarantors who are individuals, not corporations). Any personal revolving guarantee must now specify a maximum liability amount (kyokudogaku) to be valid.

- Time Limits (Principal Fixing Date - Ganpon Kakutei Kijitsu): For personal revolving guarantees securing loan-type debts, strict time limits apply. If a duration is set, it cannot exceed five years; if no duration is set, the guaranteed principal "fixes" (meaning the guarantee no longer covers new debts incurred after that point) three years from the date of the contract. However, these specific time limits (3-year/5-year rules) were not extended to all types of personal revolving guarantees during the 2017 reforms (e.g., they don't automatically apply to guarantees for leases or ongoing non-loan business transactions like the one in the 1964 case). This omission has been viewed by some commentators as a potential gap in guarantor protection for certain types of agreements.

- Statutory Grounds for "Fixing" the Principal: Instead of a general "right to terminate" future liability as developed by case law, the reformed Civil Code (Article 465-4) provides specific events that cause the guaranteed principal to "fix." These include the creditor initiating compulsory execution against the principal debtor, or the principal debtor undergoing bankruptcy proceedings (though the bankruptcy trigger is limited to guarantees for loan-type debts). The old "ordinary termination right" (based purely on passage of time) was effectively superseded by these statutory fixing rules for new guarantees.

Does the 1964 Judgment Still Matter Today?

Given the comprehensive reforms, particularly the ban on unlimited personal revolving guarantees, a case with facts identical to the 1964 scenario (an individual guarantor providing an unlimited, open-ended guarantee) would no longer arise under current law if the guarantee was made by an individual after the reforms.

However, the spirit and underlying principles of the 1964 judgment may still hold some relevance:

- For Limited Revolving Guarantees with High Caps: If a limited personal revolving guarantee (one with a maximum amount) has an exceptionally high cap that is grossly disproportionate to the guarantor's financial means and was entered into without full understanding, courts might still look to the principles of fairness and good faith, possibly influenced by the reasoning in the 1964 case. If a guarantor's trust in the principal debtor is severely undermined by the debtor's repeated misconduct, there might be arguments for an interpretative right to demand the "fixing" of the principal, even if the explicit statutory fixing events in Article 465-4 have not occurred.

- Creditor's Conduct: The 1964 case also touched upon the creditor's position. If a creditor is aware of serious issues between the principal debtor and the guarantor (like the debtor's untrustworthiness or severe financial distress) and continues to extend credit relying on the guarantee without confirming the guarantor's ongoing willingness or informing them of material changes, principles of good faith might be invoked to limit the guarantor's liability for those subsequent transactions.

Conclusion

The 1964 Supreme Court decision was a landmark in its time, offering crucial protection to guarantors caught in the bind of open-ended, unlimited revolving guarantees by recognizing their right to terminate the guarantee for future debts when their trust in the principal debtor was justifiably lost. While the Japanese Civil Code has since instituted more direct statutory protections, such as banning unlimited personal revolving guarantees and specifying "fixing events" for the guaranteed principal, the 1964 judgment's underlying concern for guarantor fairness in the face of unforeseen and escalating risks remains an important part of Japan's legal heritage. It serves as a reminder that even within contractual frameworks, fundamental principles of trust and good faith play a vital role in shaping the parties' rights and obligations.