When Time Runs Out: Japan's Supreme Court on Latent Injuries and the 20-Year Limit for Tort Claims

Date of Judgment: April 27, 2004

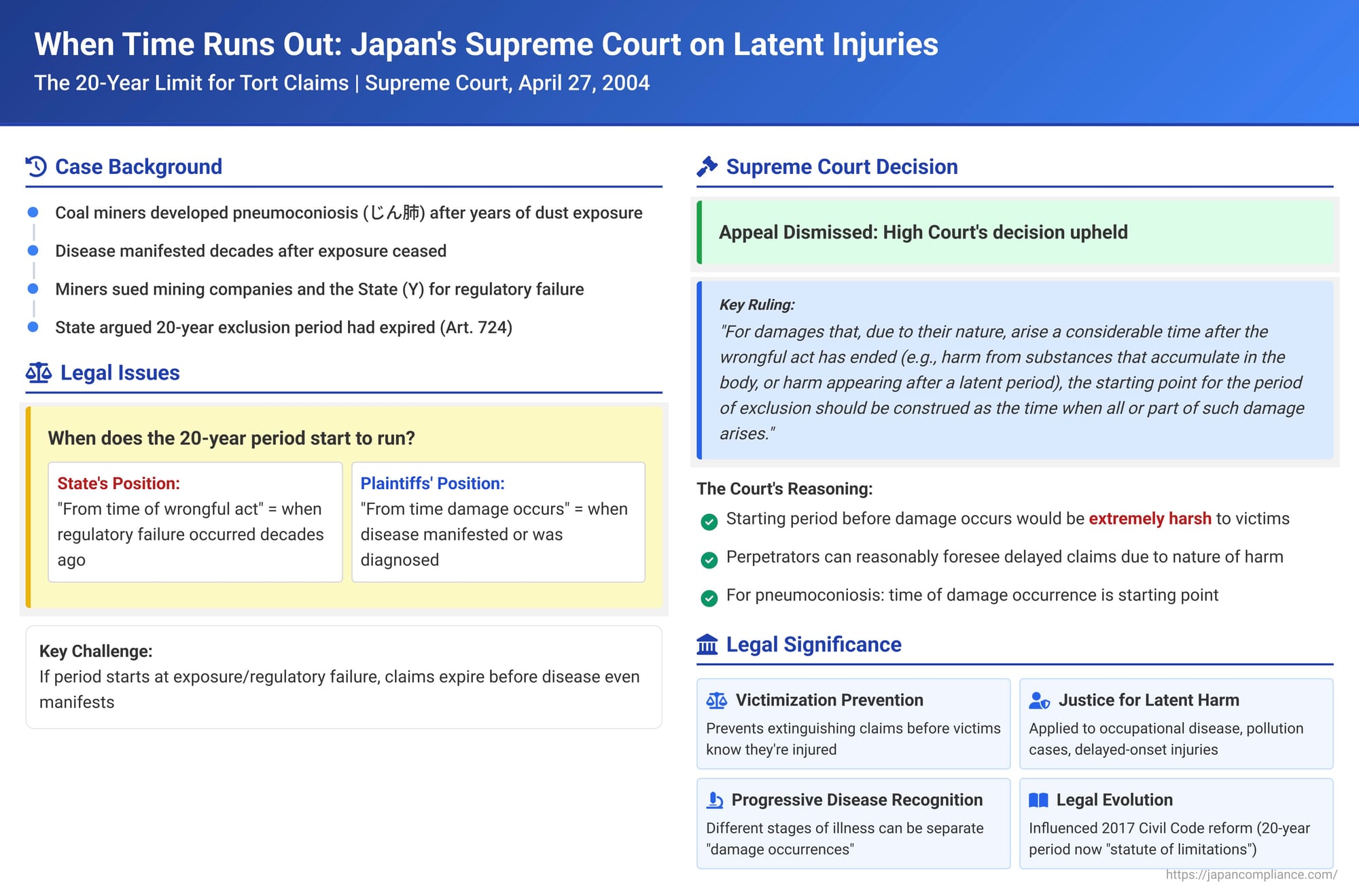

Statutes of limitations in tort law are designed to provide certainty and prevent stale claims. A common feature is a long-stop provision—often 20 years from the date of the wrongful act—after which a claim for damages is extinguished, regardless of when the victim became aware of their injury or the perpetrator. But what happens when the harm itself is insidious, lying dormant for many years only to manifest long after the exposure or wrongful act has ceased? This is a critical issue in cases of latent diseases like pneumoconiosis (miner's lung) or illnesses stemming from long-ago exposure to harmful substances. Does the 20-year clock start ticking from the moment of exposure, potentially barring a claim before the victim even knows they are ill? Or does it begin when the devastating consequences finally surface? The Supreme Court of Japan confronted this profound question in a landmark decision on April 27, 2004 (Heisei 13 (Ju) No. 1760).

The Case: Coal Miners' Decades-Later Battle Against Pneumoconiosis

The case involved numerous plaintiffs, X et al., who were former employees of coal mining companies, such as Company A, or their heirs. [cite: 1] They alleged that they, or the deceased miners whose rights they inherited, had contracted pneumoconiosis (じん肺 - jinpai), a debilitating lung disease, as a result of prolonged exposure to dust in the coal mines. [cite: 1] Their lawsuit targeted several mining companies and, significantly, Y (the State). [cite: 1] The claim against the State was based on its alleged failure to exercise its regulatory authority to implement and enforce measures that would have prevented pneumoconiosis among miners, a type of claim falling under Japan's State Compensation Law. [cite: 1]

Pneumoconiosis is characterized by the insidious accumulation of dust particles in the lungs, leading to progressive and irreversible fibrotic changes. [cite: 1] A key feature of the disease is its latency; it can take many years, sometimes decades, after exposure to dust has ended for the symptoms to appear and for the disease to be diagnosed. [cite: 1] Furthermore, the disease can continue to progress even after the individual is no longer exposed to the harmful dust. [cite: 1]

The legal battle centered on Article 724 of the Japanese Civil Code. At the time, this article contained two limitation periods for tort claims: a shorter period (typically 3 years from when the victim knew of the damage and the perpetrator) and a longer, absolute period of 20 years from "the time of the tortious act" (不法行為の時 - fuhōkōi no toki). This 20-year period was generally considered a "period of exclusion" (除斥期間 - joseki kikan), meaning it could not be interrupted or suspended and extinguished the right to claim damages absolutely. The State (Y) argued that for some of the plaintiffs, this 20-year period had already expired, contending that "the time of the tortious act" should be interpreted as the time when the State's wrongful omission (its failure to enact and enforce proper safety regulations) occurred. [cite: 1] If this interpretation were adopted, many claims would be barred because the harmful exposure and the State's failure to regulate dated back many decades.

The Fukuoka High Court, in its ruling on July 19, 2001, had taken a different view. It held that "the time of the tortious act" for this long-term period meant when the constituent elements of the tort were satisfied, including the objective occurrence of at least part of the damage. [cite: 1] Given the nature of pneumoconiosis, the High Court reasoned that specific damages (such as those recognized by administrative classifications of disease severity or death due to the disease) should be considered to have arisen at the time of such classification or death. [cite: 1] Thus, it concluded that the 20-year period started from the date of the final administrative determination of the disease stage or the date of death due to pneumoconiosis. [cite: 1] The State appealed this interpretation to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: Prioritizing Fairness for Latent Harm

On April 27, 2004, the Supreme Court dismissed the State's appeal, affirming the High Court's approach and providing a crucial interpretation of the 20-year limitation period in cases of latent harm.

The General Rule vs. The Nature of Latent Injuries

The Supreme Court began by acknowledging the standard interpretation: the starting point for the 20-year period under Article 724 (latter part, now Article 724, item 2) is "the time of the tortious act." [cite: 1] In torts where the damage occurs simultaneously with the wrongful act, the time of that act is indeed the starting point. [cite: 1]

However, the Court carved out a critical exception for specific types of harm:

"However, for damages that, due to their nature, arise a considerable time after the wrongful act has ended (e.g., harm from substances that accumulate in the body, or harm appearing after a latent period), the starting point for the period of exclusion should be construed as the time when all or part of such damage arises." [cite: 1]

Rationale for the Exception: Addressing Harshness and Foreseeability

The Supreme Court provided two primary reasons for this victim-protective interpretation:

- Extreme Harshness to Victims: The Court recognized that it would be "extremely harsh" (著しく酷 - ichijirushiku koku) for victims if the 20-year limitation period were to commence, and potentially expire, before their damage even occurred or became knowable. [cite: 1] Such an outcome would effectively deny them any real opportunity to seek compensation.

- Perpetrator's Foreseeability: The Court also considered the perspective of the perpetrator. It reasoned that those whose actions (or omissions, in the case of the State's failure to regulate) could lead to such delayed harm should, given the very nature of that potential harm, reasonably anticipate that victims might emerge and file claims for damages after a considerable period had passed. [cite: 1]

Application to Pneumoconiosis

Applying these principles to the pneumoconiosis claims, the Supreme Court noted the disease's defining characteristics: dust particles accumulating in the lungs, causing progressive fibrotic changes over an extended period, with symptoms often appearing long after the exposure to dust has ceased. [cite: 1] Given this latent and progressive nature, the Court concluded that for damages claims based on pneumoconiosis, "the time of damage occurrence should be the starting point for the period of exclusion." [cite: 1] This affirmed the High Court's decision. [cite: 1]

This was the first Supreme Court judgment to directly address whether "the time of the tortious act" for the long-term limitation period should be interpreted as the time of the wrongful act itself (the "act-time theory") or the time when the damage actually occurs (the "occurrence-time theory"). [cite: 1] The Court effectively endorsed the occurrence-time theory for latent injuries.

Understanding "Time of Damage Occurrence" in Progressive Diseases

While the Supreme Court established that damage occurrence is the key, pinpointing that precise moment in a progressive disease like pneumoconiosis presents its own complexities. The judgment did not set a universal, concrete starting point for all latent diseases but, by upholding the lower court, implicitly supported an approach that recognizes the evolving nature of such harm. The lower court had considered the dates of specific administrative classifications of disease severity or the date of death due to pneumoconiosis as relevant markers for when particular damages arose. [cite: 1]

This aligns with other Supreme Court precedents, such as a Heisei 6 (1994) judgment concerning pneumoconiosis (in the context of a different limitations rule), which acknowledged that damages corresponding to different, progressively more severe administrative classifications of the disease could be seen as "qualitatively different." [cite: 1] This implies that as the disease worsens and new, more severe stages of harm are recognized, these can be considered as fresh "occurrences" of damage. [cite: 1] The full impact of the disease is not necessarily fixed or ascertainable at the moment of initial exposure or when the very first symptoms appear.

The "All or Part of Such Damage" Nuance

The Supreme Court's statement that the period commences "when all or part of such damage arises" also warrants careful consideration. [cite: 1] Legal scholars have discussed at least two interpretations of this phrase: [cite: 1]

- One interpretation is that the first manifestation of any harm (a "part") stemming from the tortious act starts the 20-year clock for all potential future harm related to that act, provided later harm is foreseeable from that initial damage. [cite: 1]

- Another interpretation, particularly relevant for uncertain, progressive diseases like pneumoconiosis, is that "part" refers to a qualitatively distinct stage of damage. [cite: 1] As the disease progresses and more severe stages are reached, each of these could be considered a "part" of the damage, potentially triggering the limitation period for that specific increment of harm. The "whole" damage, such as a fatal outcome, might have the latest starting point. [cite: 1]

Given that the Supreme Court in this 2004 case affirmed the lower court's approach, which focused on final administrative decisions or death in the context of pneumoconiosis, the latter interpretation—recognizing that different stages of qualitatively distinct harm can trigger the period for that specific harm—appears more aligned with the judgment's spirit for such progressive conditions. [cite: 1]

Scope and Implications of the Ruling

This 2004 decision has profound implications, especially for victims of latent occupational diseases, illnesses caused by long-term environmental pollution, and other torts where the injurious consequences are significantly delayed.

The core reasoning—fairness to victims who cannot know of their harm and the reasonable expectation that perpetrators of acts causing latent harm should anticipate delayed claims—suggests a protective stance. [cite: 1] While the ruling explicitly addresses harm from substances accumulating in the body or diseases manifesting after a latent period, academic discussion continues on its precise scope. [cite: 1] Some scholars argue that its application might be focused on "uncertain progressive" personal injuries, where the full extent and timing of the harm are not clear from the outset. [cite: 1] Others suggest that the underlying principle of not being able to claim for damage that has not yet occurred could give the ruling a broader reach to other types of late-occurring damage. [cite: 1]

Following this judgment, lower courts in Japan have applied its framework to various latent harm scenarios, including further pneumoconiosis cases, late-onset Minamata disease (a neurological syndrome caused by severe mercury poisoning), cases of higher brain dysfunction appearing after traumatic brain injury, and depression manifesting after experiences of sexual abuse. [cite: 1] These cases largely involve personal injuries characterized by latency, accumulation, and often an uncertain or progressive course. [cite: 1] The question of how this principle applies to other types of delayed damage, such as the collapse of a defectively constructed building 21 years after completion, remains a subject for ongoing legal debate. [cite: 1]

Impact of Subsequent Civil Code Reforms

It's important to note a significant subsequent development in Japanese law. At the time of the 2004 ruling, the 20-year period in Article 724 was generally understood by the Supreme Court to be a "period of exclusion" (joseki kikan), which is a strict, absolute time limit that cannot typically be interrupted or suspended. [cite: 1] However, the Japanese Civil Code was substantially reformed in 2017 (with effect from 2020). The reformed Article 724, item 2 now explicitly designates this 20-year period as a "statute of limitations" (shōmetsu jikō). [cite: 1]

While the 2004 judgment operated on the premise of an exclusion period, its foundational reasoning remains compelling. The shift in the legal nature of the 20-year period to a statute of limitations might, if anything, strengthen the rationale for an occurrence-time starting point. [cite: 1] Statutes of limitation are generally understood not to begin running before a right can actually be exercised. [cite: 1] Furthermore, characterizing the period as a statute of limitations might, in some future cases, allow victims to invoke general doctrines applicable to statutes of limitations, such as the principle against abuse of the right to plead prescription, if a strict application of the time bar would lead to a grossly unjust result. [cite: 1]

Conclusion: Ensuring a Fair Chance for Justice in Latent Harm Cases

The Supreme Court of Japan's decision of April 27, 2004, is a critical marker in the nation's tort law, particularly for its compassionate and pragmatic approach to victims of latent harm. By ruling that the 20-year absolute time limit for bringing a tort claim starts from the occurrence of damage in cases of delayed-onset injuries—rather than from the date of the original wrongful act or exposure—the Court significantly enhanced the possibility of justice for individuals suffering from conditions like pneumoconiosis. This judgment underscores a fundamental commitment to fairness, ensuring that the courthouse doors are not prematurely closed to those whose injuries, by their very nature, take many years to reveal their devastating impact. It balances the need for legal certainty with the profound unfairness of extinguishing a claim before it can even be recognized.