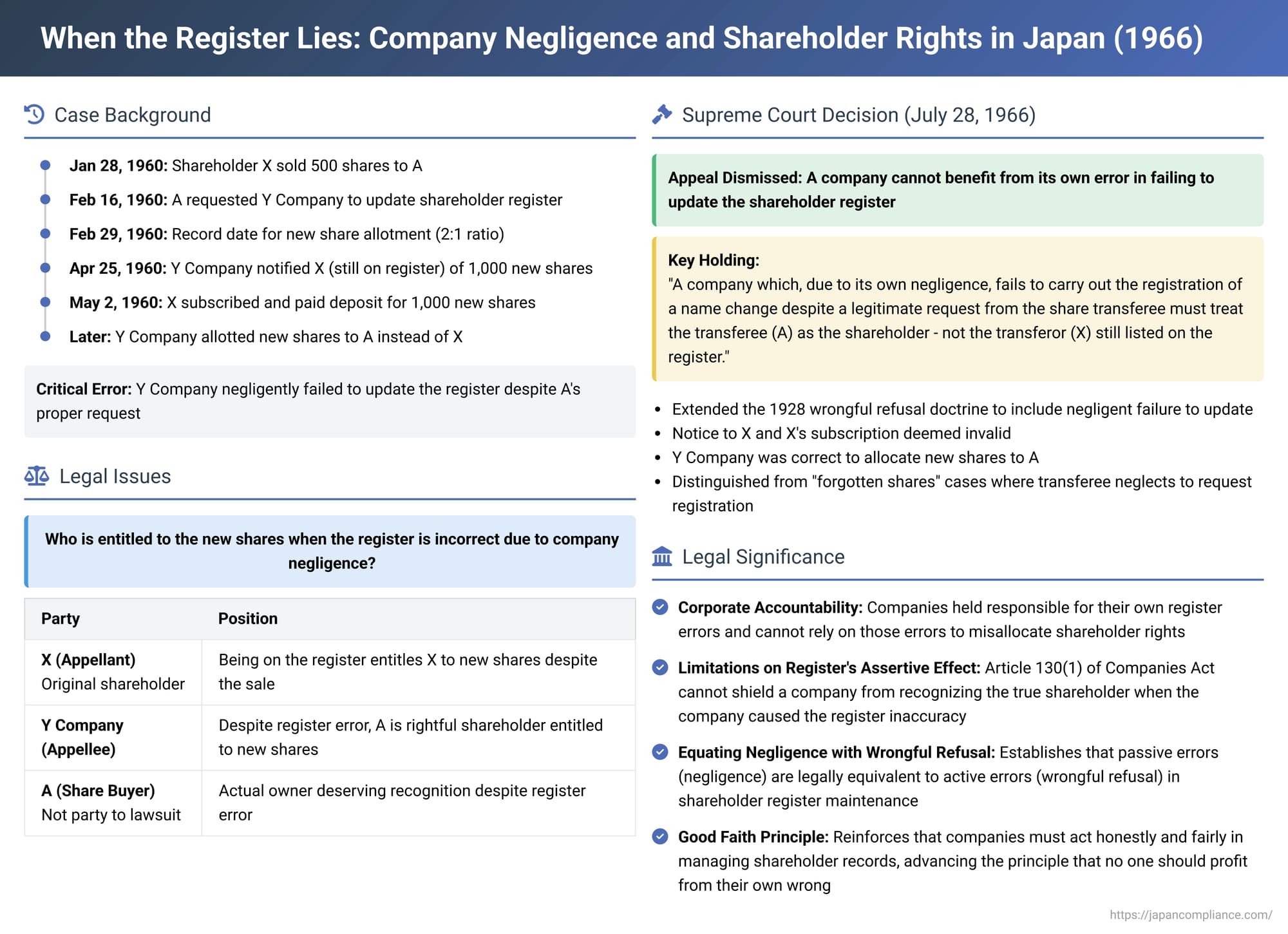

When the Register Lies: Company Negligence and Shareholder Rights in Japan

Judgment Date: July 28, 1966

Case: Share Delivery Claim Case (Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench)

This case from Japan's Supreme Court delves into a critical issue in corporate law: what happens when a company, due to its own negligence, fails to update its shareholder register after a legitimate share transfer? Who does the company recognize as the rightful shareholder, especially concerning new share allotments – the seller still on the register or the buyer who duly requested the change? The ruling provides a clear answer, emphasizing that a company cannot benefit from its own errors.

Factual Background: A Share Sale and a Missed Update

The dispute involved an individual, X (the appellant), Y Company (the appellee), and a third-party, A.

Y Company's board of directors resolved on December 2, 1959, to issue new shares. The terms were as follows:

- New shares would be allotted to shareholders listed on the company's shareholder register as of 5:00 PM on February 29, 1960 (the "record date"). The allotment ratio would be two new shares for every one existing share held.

- The subscription period for these new shares would be from April 25, 1960, to May 10, 1960.

- The payment date for the new shares would be May 21, 1960.

- A subscription deposit of JPY 50 per share was required, which would be applied to the full payment on the payment date.

Prior to this record date, on January 28, 1960, X, who was a shareholder in Y Company, sold 500 of their existing shares to A. Following this purchase, on February 16, 1960—still before the record date—A formally requested Y Company to update the shareholder register to reflect this transfer of ownership (a process known as "meigi kakikai").

Crucially, Y Company, due to its own negligence, failed to process this name change request. Consequently, as of the record date (February 29, 1960), X incorrectly remained listed as the owner of those 500 shares in the shareholder register.

Because X was still listed as the shareholder, Y Company notified X on April 25, 1960, of an allotment of 1,000 new shares (based on the 2:1 ratio for the 500 shares X supposedly still held). Subsequently, on May 2, 1960, X applied to subscribe to these 1,000 new shares and paid the required deposit of JPY 50,000.

Later, Y Company presumably realized its error or otherwise determined that A was the rightful party to receive the benefits of the new share issuance related to the shares A had purchased. Y Company proceeded to allot the new shares corresponding to the original 500 shares to A.

Aggrieved by not receiving the new shares she had subscribed to based on the company's notice, X filed a lawsuit against Y Company, demanding the delivery of these new shares. Both the court of first instance and the appellate court dismissed X's claim. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Company Error Cannot Trump True Ownership

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, upholding the lower courts' decisions. The Court's reasoning was clear and direct:

The judgment stated that a company which, without justifiable cause, refuses a request for the registration of a share transfer cannot then deny the validity of that transfer based on the fact that the register has not been updated. This principle was established in an earlier Great Court of Cassation (Daishin-in, the predecessor to the Supreme Court) judgment from July 6, 1928.

Therefore, in such situations, the company is obligated to treat the share transferee (the buyer, A, in this case) as the legitimate shareholder. Conversely, the company is not permitted to treat the transferor (the seller, X), who is still listed on the shareholder register, as the shareholder.

The Supreme Court explicitly extended this principle: the same reasoning applies when a company, due to its own negligence, fails to carry out the registration of a name change despite a legitimate request from the share transferee.

Applying this to the current case:

- A had lawfully requested the name registration for the shares acquired from X before the record date.

- Y Company negligently failed to execute this registration.

- Despite the shareholder register not being updated, Y Company was required to treat A (the transferee) as the shareholder for those shares.

- Consequently, Y Company could not treat X (the transferor) as the shareholder, even though X's name remained on the register.

The Supreme Court concluded that X's claim for the new shares, which was predicated on X being the registered shareholder on the record date, was correctly rejected by the lower courts. The Court also distinguished a case cited by X, noting it pertained to "forgotten shares" where a transferee had neglected to request registration, a situation entirely different from the present one where the company was at fault.

The Court also found no error in the lower court's determination that the new share allotment notice sent to X (who had no right to such an allotment) and X's subsequent subscription were both invalid.

Unpacking Japanese Company Law: Share Transfers and the Shareholder Register

To fully appreciate the Supreme Court's decision, it's helpful to understand some foundational aspects of Japanese company law regarding shares and their registration.

1. The Shareholder Register (Kabunushi Meibo): A Cornerstone of Corporate Administration

Japanese companies are required to maintain a shareholder register (Companies Act, Article 121). This register meticulously records the names and addresses of shareholders, the number of shares they hold, the date of acquisition, and (for companies issuing share certificates) the serial numbers of those certificates if issued.

The register is paramount for the company to identify who its shareholders are, to whom it should send notices, pay dividends, and grant voting rights or other shareholder prerogatives like new share allotments.

2. Transfer of Name on the Register (Meigi Kakikai)

When shares are transferred, the buyer (transferee) typically needs to have their name entered into the shareholder register to be recognized by the company as the new shareholder.

- For Companies Issuing Share Certificates: The transferee generally presents the share certificates to the company to request the name change (Companies Act, Article 133(2); Ordinance for Enforcement of the Companies Act, Article 22(2)(i)).

- For Companies Not Issuing Share Certificates (and not using the book-entry system): The transfer is generally effected by a joint request from both the transferor and transferee to the company (Companies Act, Article 133(2)).

- Book-Entry System: For companies whose shares are handled through the book-entry transfer system (governed by the Act on Book-Entry Transfer of Company Bonds, Shares, etc.), the issue of wrongful refusal of name registration by the company itself largely doesn't arise. Updates to the shareholder register are typically made automatically based on notifications from the book-entry transfer institutions (See Articles 151 and 152 of the Book-Entry Transfer Act). This case predates the widespread adoption of such systems.

"Wrongful refusal of name registration" refers to situations where the company, without a legitimate reason, rejects or fails to act upon a proper request to update the shareholder register. This case confirms that mere negligence leading to such failure has the same consequence as an outright wrongful refusal.

3. Legal Effects of the Shareholder Register

The shareholder register is not merely an administrative tool; it has significant legal effects:

- Qualifying Effect (Shikaku Juyo Teki Koryoku): Being listed on the shareholder register generally qualifies a person as a shareholder in their dealings with the company. The company uses the register to determine who can exercise shareholder rights.

- Assertive/Definitive Effect (Taiko Koryoku / Kakutei Teki Koryoku): Article 130(1) of the Companies Act states that a transfer of shares (for companies that issue share certificates or for certain other types of shareholdings not under the book-entry system) cannot be asserted against the company unless the name and address of the acquirer are recorded in the shareholder register. This is a crucial provision. It means that, ordinarily, if you're not on the register, the company doesn't have to recognize you as a shareholder.

- Exempting/Protective Effect (Menseki Teki Koryoku): When a company, in good faith and without negligence, deals with the person recorded in the shareholder register as the shareholder (e.g., pays dividends or gives voting rights), the company is generally protected from claims by a true owner whose name was not yet registered. This effect ensures the company can rely on its register for orderly administration.

The interplay of these effects, especially the assertive effect of Article 130(1) and the company's potential fault, is central to understanding cases like the one at hand.

Analysis of the Judgment in Light of Corporate Law Principles

The Supreme Court's 1966 decision reinforces a fundamental principle of fairness and good faith in corporate dealings.

1. Judicial Evolution: Beyond Strict Adherence to the Register

Historically, there might have been a stricter adherence to the letter of the law, potentially allowing a company to rigidly rely on its (erroneous) register. However, Japanese case law, notably since the 1928 Great Court of Cassation decision cited by the Supreme Court in this very case, has evolved. This evolution recognizes that if the company itself is responsible for the register's inaccuracy—either through a wrongful refusal or, as clarified here, through negligence—it cannot hide behind Article 130(1) of the Companies Act to deny the rights of the legitimate transferee.

The 1966 judgment explicitly equates the company's negligence in failing to update the register with a wrongful refusal. This is significant because it prevents a company from claiming a lower standard of responsibility for passive errors (negligence) compared to active ones (wrongful refusal). Both undermine the integrity of the share transfer process and the rights of the transferee. The underlying rationale is often linked to the principle of good faith (shin'gi-soku), which dictates that parties should act honestly and fairly, and a company should not profit from its own lapse.

2. Impact on the Transferor (X) and Transferee (A)

The most direct consequence of the judgment is the clarification of the parties' standing:

- The Transferee (A): Despite not being on the register due to Y Company's error, A is to be treated as the shareholder by Y Company. A was therefore entitled to the new share allotment.

- The Transferor (X): Even though X was still on the register, X could not be treated as the shareholder by Y Company concerning the transferred shares. X's attempt to claim the new shares was therefore unfounded.

This case is particularly noteworthy because it wasn't the unregistered transferee (A) suing the company to be recognized. Instead, it was the erroneously registered transferor (X) attempting to exercise rights, and the company's (and ultimately the court's) position was effectively that X had no such rights because A should have been recognized. The company's failure to register A's title became the basis for denying X's claim.

3. The "Assertive Effect Limitation Theory" (Taiko-ryoku Seigen Setsu) vs. "Definitive Theory" (Kakutei Setsu)

The interpretation of Article 130(1) of the Companies Act (which states an unregistered shareholder cannot assert rights against the company) has been a subject of academic discussion.

- The Definitive Theory (Kakutei Setsu) might suggest a very strict interpretation: if you're not on the register, the company generally cannot recognize you, and you cannot demand recognition, with very limited exceptions.

- The prevailing view, however, is the Assertive Effect Limitation Theory (Taiko-ryoku Seigen Setsu). This theory posits that Article 130(1) primarily means that an unregistered shareholder cannot force the company to recognize them. However, the company may choose to recognize an unregistered shareholder if it is willing to accept any associated risks (e.g., if the person turns out not to be the true owner).

If the majority view (Assertive Effect Limitation Theory) allows a company to voluntarily recognize an unregistered shareholder, why was Y Company's negligence in failing to register A so crucial in this case for determining that A, not X, was the shareholder?

The commentary surrounding such cases suggests this distinction can be important for the company's "exempting effect." If a company voluntarily deals with an unregistered shareholder, it does so at its own risk and might not be protected if, for instance, it pays a dividend to the wrong person. However, if the situation is one where the company wrongfully or negligently failed to register the true owner, the legal treatment leans towards viewing the situation as if the registration had been properly made. In such a scenario, the company, by treating the actual (but unregistered) transferee as the shareholder, might still benefit from the exempting effect, as it is acting in accordance with its obligation stemming from its own prior fault. Its actions are not purely voluntary but rather a correction of its error.

4. Negligence Leading to Failure vs. Deemed Completion of Registration

Another line of thought in Japanese corporate law suggests that in certain situations of company error, particularly where the failure to complete registration is a mere administrative oversight despite the company's intention to register, the registration might be considered legally complete. This view would distinguish between a malicious refusal and a simple, negligent lapse in internal procedures.

The Supreme Court's judgment in this case, however, doesn't delve into such a distinction for "negligent failure." It groups company negligence leading to non-registration with outright wrongful refusal, with the common outcome that the company must treat the transferee as the shareholder. The focus is less on whether the registration is "deemed complete" and more on the company's duty to recognize the party who rightfully sought registration.

Broader Implications and Related Considerations

The principles highlighted in this 1966 judgment resonate with other related issues in Japanese corporate law:

1. Asserting Shareholder Rights Against Third Parties

For shares in companies that do not issue share certificates, Article 130(1) of the Companies Act also means that registration on the shareholder register is generally required to assert one's status as a shareholder against third parties (not just the company). This raises a question: if a company wrongfully refuses to register a transfer, can the transferee still assert their shareholder status against a third party (e.g., another claimant to the same shares)?

- One view is that, generally, the transferee cannot assert their status against third parties unless the third party was acting in bad faith (e.g., knew about the wrongful refusal or the company's habitual non-compliance).

- An alternative view argues that if the company's refusal was wrongful, the situation should be treated as if registration occurred, thereby allowing the transferee to assert their rights against third parties as well. The answer often depends on how broadly the corrective effect of the "wrongful refusal" doctrine is interpreted.

2. Constructive or De Facto Wrongful Refusal

There have been instances where, even if a formal registration request wasn't made or was somehow deficient, courts have found a "de facto" wrongful refusal. This might occur if it's abundantly clear that the company would reject any such request from the rightful shareholder, knows the person is the owner, and that ownership can be easily proven. In such cases, the courts might allow the shareholder to assert rights against the company as if a wrongful refusal had occurred. This contrasts with situations where shareholder status is genuinely in dispute (e.g., due to ongoing litigation over a will bequeathing shares), where a company's caution in registering a transfer would likely not be deemed a wrongful refusal.

3. Succession and Name Registration

In cases of universal succession, such as inheritance, the prevailing academic view and practice generally require the heir to undergo the name registration process to assert their shareholder rights against the company, even though they acquire the shares automatically by operation of law. While there was some initial indication from drafters of the Companies Act that registration might not be necessary for heirs to assert their status, the mainstream interpretation favors requiring registration for clarity and order in company administration.

Conclusion: Corporate Accountability in Record-Keeping

The Supreme Court's July 1966 decision underscores a vital tenet of corporate responsibility: a company cannot use its own administrative failures—be it deliberate refusal or mere negligence—to misallocate shareholder rights. When a shareholder properly requests the registration of a share transfer, and the company fails to act, the company must nevertheless recognize the transferee as the true shareholder. The seller, still listed on the register due to the company's error, loses their standing as shareholder for those transferred shares. This principle ensures that the integrity of the shareholder register system is maintained not by rigid formalism, but by an underlying commitment to fairness and the recognition of rightful ownership, holding companies accountable for the accuracy of their own records.