When the Land is Reshaped: Legal Challenges to Completed Projects in Japan

Judgment Date: January 24, 1992

Case Number: 1990 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 153 – Revocation of Land Improvement Project Implementation Approval

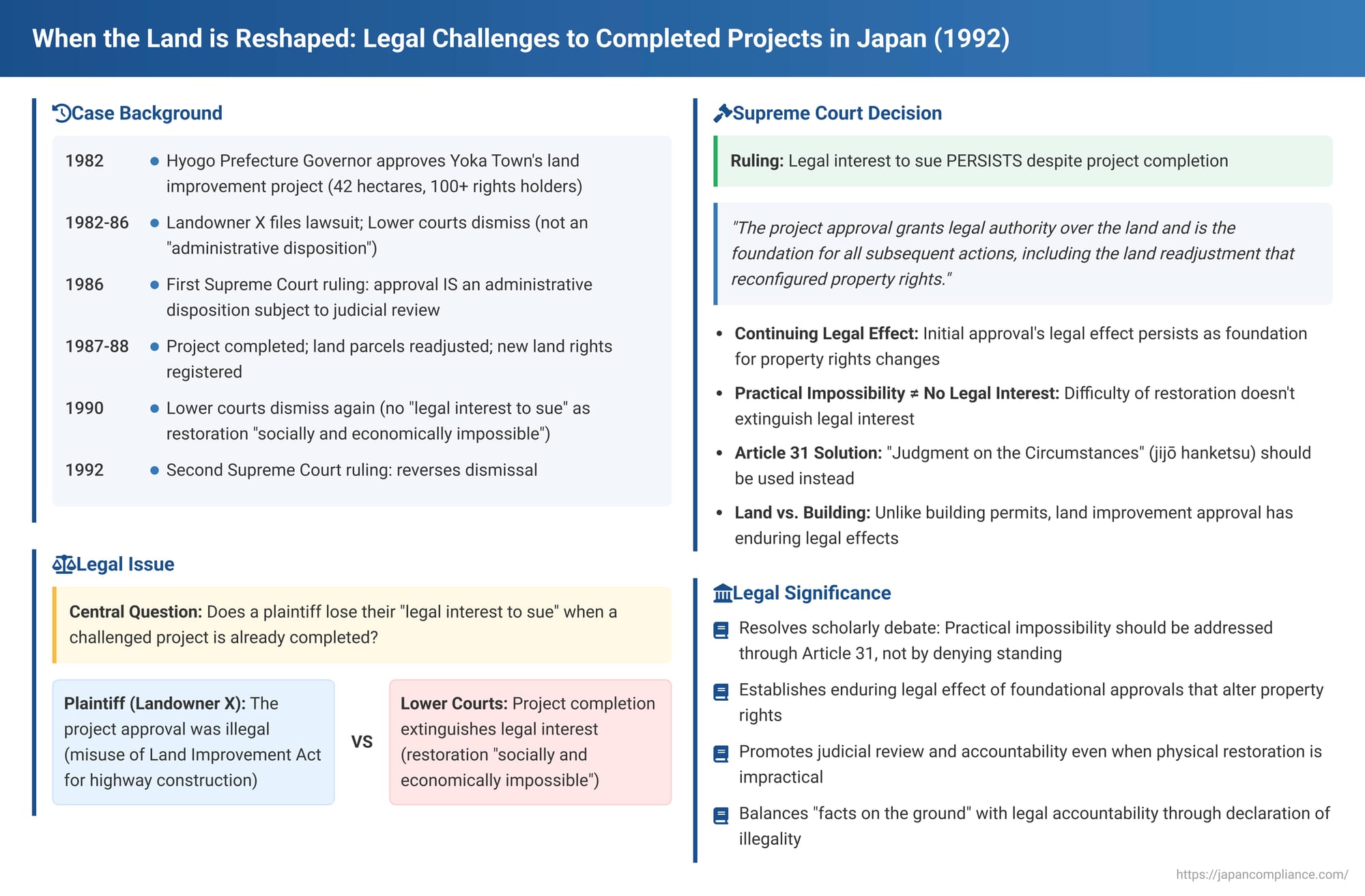

What happens when a government-approved project, challenged in court for its legality, is completed before the judges can render a final verdict? This scenario presents a significant dilemma: does the completion render the lawsuit meaningless, even if the initial approval was flawed? The Japanese Supreme Court tackled this question head-on in a pivotal 1992 decision concerning a land improvement project in Yoka Town, Hyogo Prefecture. The ruling clarified the crucial difference between the practical difficulty of undoing a completed project and a citizen's continuing legal interest in challenging the project's foundational approval.

The Yoka Town Project: Farmland Improvement or Highway Diversion?

The case began when the Governor of Hyogo Prefecture (the Defendant/Appellee, "Y") granted approval to Yoka Town on September 30, 1982, for a municipal land improvement project (tochi kairyō jigyō). This approval was publicly announced on October 12, 1982. X, a landowner within the designated project area, filed a lawsuit seeking to revoke this approval.

X's core contention was that the project was an abuse of the Land Improvement Act. X alleged that its true purpose was not to benefit agriculture but to facilitate the construction of a new bypass for National Highway Route 9. Consequently, X argued, the project did not meet the statutory definition of a land improvement project under Article 2, Paragraph 2 of the Act, and it lacked the requisite necessity and comprehensiveness mandated by the Act's enforcement ordinance.

A Winding Road Through the Courts

The legal journey was lengthy and complex.

- Initial Lower Court Rulings: The first set of lower court decisions dismissed X's suit, finding that the approval for the project implementation was not an "administrative disposition" (gyōsei shobun) that could be challenged through a revocation lawsuit.

- First Supreme Court Intervention (1986): X appealed, and in a significant 1986 decision, the Supreme Court reversed the lower courts. It held that the approval did constitute an administrative disposition subject to judicial review, likening its role and impact to that of project decisions in nationally or prefecturally operated land improvement schemes. The case was remanded back to the Kobe District Court for further proceedings.

Crucially, while the litigation was ongoing, Yoka Town proceeded with the project. By March 1987, all construction work under the project plan was completed. A land readjustment plan (kanchi keikaku) was formulated, and after public notice and review, Y approved this plan on December 16, 1987. Yoka Town carried out the land readjustment disposition (kanchi shobun)—a process of reallocating land parcels to owners—on December 22, 1987. The corresponding property registrations were finalized on February 1, 1988. The total project cost amounted to approximately 270.56 million yen, affecting an area of 39.4 hectares (later expanded to 42 hectares) and involving around 100 rights holders. X also received two parcels of land through this readjustment.

- Post-Remand Lower Court Rulings: When the case returned to the Kobe District Court, it was again dismissed on February 21, 1990, but for a different reason. The court, acknowledging the completion of the project, the substantial investment, and the finalized land readjustment, ruled that X no longer had a "legal interest to sue" (uttae no rieki). It reasoned that restoring the area to its original state was, if not physically impossible, then "socially and economically impossible" given the significant losses that would entail. Therefore, revoking the initial approval would serve no practical purpose. The Osaka High Court upheld this dismissal on June 28, 1990.

X appealed to the Supreme Court for a second time.

The Supreme Court's 1992 Decision: Legal Interest Survives Practical Hurdles

On January 24, 1992, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court delivered its judgment, decisively overturning the lower courts' dismissal and remanding the case back to the Kobe District Court. The Supreme Court’s reasoning centered on the nature of the legal interest to sue and how it interacts with the practicalities of a completed project.

The Enduring Legal Effect of the Initial Approval

The Supreme Court began by clarifying the legal significance of the initial project approval:

- It grants the project implementer (Yoka Town) the legal authority—the "right to implement a land improvement project" (tochi kairyō jigyō shikōken)—over the land within the project area.

- All subsequent procedures and administrative dispositions within the project, most notably the land readjustment disposition (kanchi shobun), are legally predicated on the valid existence of this initial approval.

- Consequently, if the initial approval were to be revoked by a court judgment, the legal validity of these subsequent actions, including the land readjustment that reconfigured property rights, would inevitably be affected. If the initial approval is nullified, any subsequent land exchange disposition loses its foundation, potentially reviving original property rights and creating a legal obligation for restoration.

"Socially and Economically Impossible" Restoration: A Matter for Article 31

The core of the Supreme Court's decision lay in how to treat the argument that restoration was "socially and economically impossible."

- The Court held that such practical impossibility, stemming from the completion of construction and land readjustment during the pendency of the lawsuit, does not extinguish the plaintiff's legal interest in seeking the revocation of the initial approval.

- Instead, these circumstances—the significant social and economic losses that would result from attempting to undo the completed project—are precisely the kind of factors to be considered under Article 31 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act. This article provides for a "judgment on the circumstances" (jijō hanketsu).

Understanding the "Judgment on the Circumstances" (Jijō Hanketsu)

Article 31 allows a court, even if it finds an administrative disposition illegal, to dismiss the plaintiff's claim for revocation if annulling the disposition would cause serious harm to the public interest. However, when rendering such a judgment, the court must explicitly declare the illegality of the disposition in the main text of its judgment.

This declaration of illegality is not merely symbolic. It has res judicata effect, meaning it is legally binding. For instance, if a plaintiff subsequently files a state compensation (damages) lawsuit concerning the same illegal disposition, the issue of its illegality cannot be re-litigated by the state.

Distinction from Building Permit Cases

The legal effect of an approval for a land improvement project, which includes land readjustment, differs from that of a building confirmation (permit). In cases where a building permit is challenged after construction is complete (e.g., Supreme Court, October 26, 1984), the legal interest to sue for revocation of the permit is often lost. This is because the building permit's primary legal effect (authorizing the commencement of construction) is considered exhausted upon completion, and subsequent regulatory actions like completion inspections or correction orders for the existing building are based on different legal criteria, not solely on the validity of the original permit.

In contrast, the approval for a land improvement project underpins the entire sequence of subsequent actions, including the land readjustment which permanently alters property rights. Its legal effect continues to support these altered rights even after project completion. Therefore, its revocation would legally undermine these ongoing rights.

Why a Jijō Hanketsu Matters More Than Dismissal

The Supreme Court's decision to favor the jijō hanketsu route over outright dismissal for lack of legal interest has significant benefits for a plaintiff in X's position:

- Preserves Judicial Review: It ensures that the legality of the initial administrative action can still be judicially determined, even if the project has advanced significantly.

- Vindication and Legal Foundation: A declaration of illegality in a jijō hanketsu provides official vindication for the plaintiff's claim that the administration acted unlawfully. More importantly, it provides a solid legal basis for subsequent claims, particularly for damages.

- Avoids Premature Termination: Dismissing the suit for lack of legal interest due to practical unfeasibility of restoration effectively shields the initial administrative act from a full review of its legality once enough "facts on the ground" have been created. The Supreme Court's approach prevents this.

It should be noted that the plaintiff X was not arguing for a jijō hanketsu as the basis for their standing; rather, they sought full revocation. However, the Court's decision clarified that the possibility of a jijō hanketsu is the proper way to handle the tension between an illegal act and irreversible consequences, not by denying standing.

Significance of the 1992 Ruling

This Supreme Court judgment is a landmark for several reasons:

- It definitively resolved a long-standing debate among legal scholars and in lower court precedents regarding whether the practical impossibility of restoring the original state extinguishes the legal interest to sue or whether it should be dealt with through a judgment on the circumstances. The Court firmly endorsed the latter.

- It reinforces the importance of the initial project approval as a foundational legal act whose validity underpins all subsequent project components, including land title readjustments.

- It champions a plaintiff's access to a judicial determination on the legality of an administrative action, even when physical realities make a complete remedy impractical. The focus shifts to what legal pronouncements are still meaningful.

- The principle of non-suspension of execution (whereby filing a lawsuit doesn't automatically halt the challenged administrative action) means that projects often continue during litigation. This ruling provides a crucial mechanism for courts to address illegalities discovered after substantial completion without necessarily causing massive public disruption, while still holding the administration accountable through a declaration of illegality.

- This approach aligns with later Supreme Court jurisprudence, such as a 2012 decision involving a Labor Relations Commission order, where the Court affirmed that factual difficulties in implementing an order, short of objective impossibility, do not nullify its legal effect or the interest in challenging it.

Conclusion: Upholding Legal Review in the Face of Irreversible Change

The Supreme Court's 1992 decision in the Yoka Town land improvement project case underscores a vital principle: the practical difficulty of undoing a completed project does not automatically negate a citizen's legal interest in challenging the lawfulness of the project's initial approval. By directing such situations towards the "judgment on the circumstances" mechanism, the Court ensures that the legality of administrative actions can still be scrutinized and declared, providing a pathway for accountability and potential redress (like damages), even when the clock cannot be turned back on the physical changes. This judgment strikes a balance between recognizing the finality of complex projects and upholding the fundamental right to judicial review of government actions.