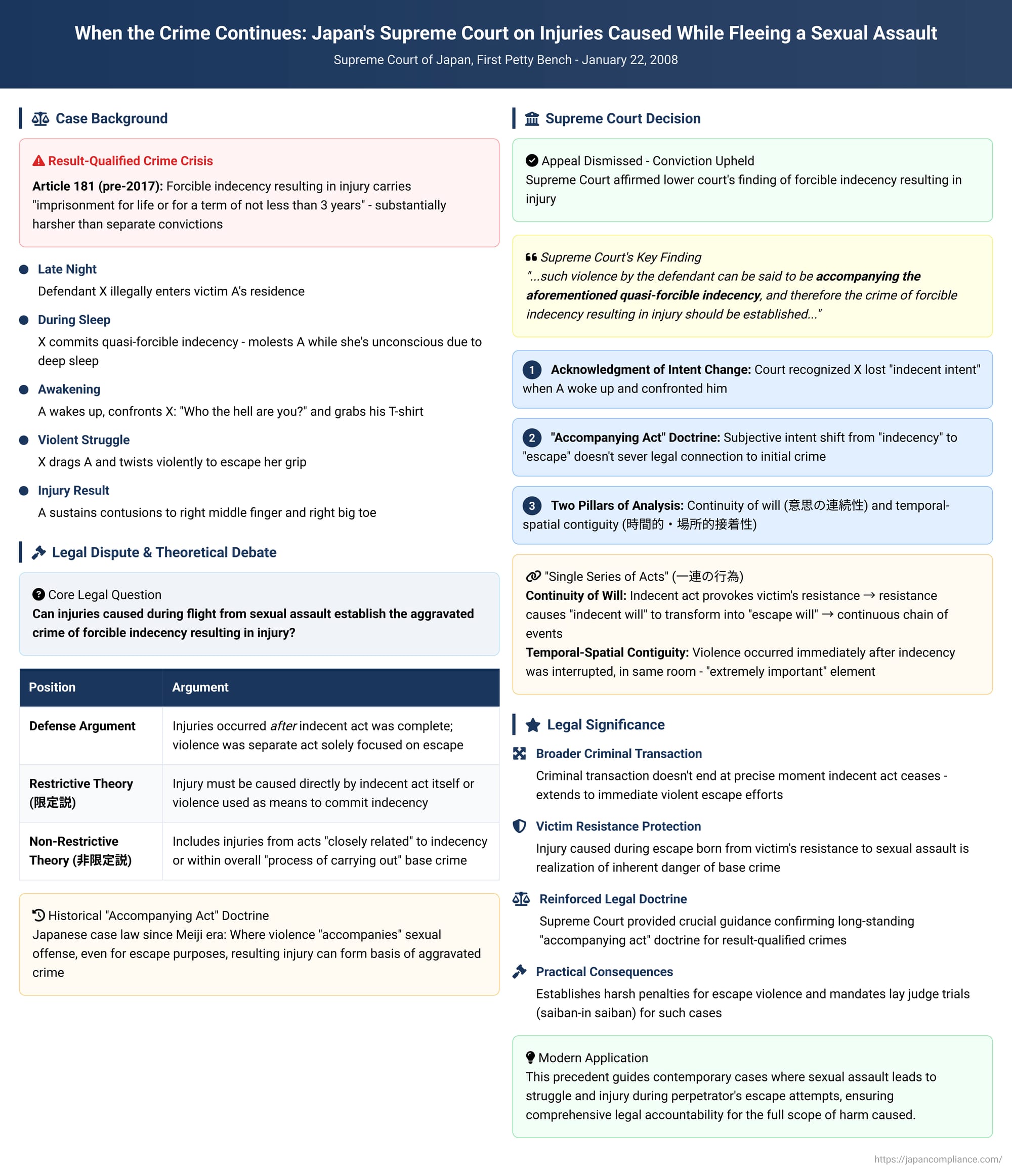

When the Crime Continues: Japan's Supreme Court on Injuries Caused While Fleeing a Sexual Assault

In the complex realm of criminal law, defining the precise moment a crime ends can be as crucial as defining when it begins. This is particularly true for "result-qualified crimes," where a base offense is punished more severely because it leads to a graver outcome, such as injury or death. A critical question often arises: what if the injury occurs not during the primary criminal act, but in the immediate, chaotic aftermath as the perpetrator tries to escape?

On January 22, 2008, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued a pivotal decision in just such a case, addressing whether an injury caused during a flight from the scene of a sexual assault could establish the crime of forcible indecency resulting in injury. The ruling delves into the intricate concepts of causation, intent, and what it means for one act to "accompany" another, offering a crucial interpretation with significant practical consequences. A conviction for forcible indecency resulting in injury carries a penalty of "imprisonment for life or for a term of not less than 3 years," a substantially harsher sentence than separate convictions for indecency and assault, and it also mandates a trial by a lay judge panel (saiban-in saiban).

The Facts of the 2008 Case

The case centered on the actions of the defendant, X, late one night. The facts, as established by the lower courts and affirmed by the Supreme Court, were as follows:

- X illegally entered the residence of the victim, A.

- He found A asleep and, taking advantage of her state of unconsciousness due to deep sleep, he molested her by fondling her private parts over her underwear. This act constitutes "quasi-forcible indecency," which applies when the victim is in a state of unconsciousness or unable to resist.

- The act caused A to awaken. She immediately confronted X, demanding in a strong tone, "Who the hell are you?" and grabbed the back of his T-shirt with both hands.

- In an effort to escape, X struggled violently. He dragged A and twisted his upper body intensely to break her grip.

- As a direct result of this struggle, A sustained injuries, specifically contusions to her right middle finger and right big toe.

The defendant appealed his conviction, arguing that the injuries occurred after he had completed the indecent act and was solely focused on escaping. Therefore, he contended, the act of violence causing the injury was separate from the indecency, and he should not be convicted of the single, aggravated crime of forcible indecency resulting in injury.

The Legal Conundrum: Defining the Boundaries of a Single Criminal Act

The case forced the Court to clarify the scope of Article 181 of the Penal Code (pre-2017 amendment), which establishes the crime of forcible indecency resulting in injury or death. This type of offense is known as a result-qualified crime (kekkateki kajūhan), where the law prescribes a heavier punishment because the commission of a base crime (like indecency) has a specific, dangerous tendency to lead to a more severe result (like injury).

The central legal debate has long revolved around how tightly the resulting injury must be connected to the base crime of indecency. Scholarly opinion has been divided.

- The Restrictive Theory (限定説): Proponents of this view argue that for the aggravated crime to be established, the injury must be caused directly by the indecent act itself or by the violence and threats used as the means to commit the indecency. This view often points to the difference in wording between the statute for robbery-injury (Art. 240), which is interpreted broadly to cover any injury caused "on the occasion of the robbery," and the statute for indecency-injury (Art. 181), whose wording suggests a more direct causal link is required.

- The Non-Restrictive Theory (非限定説): This opposing view argues that the causal act is not so narrowly limited. While not boundless, this theory would include injuries resulting from acts that are "closely related" to the indecency or that occur within the overall "process of carrying out" the base crime.

Japanese case law, dating back to the Meiji era, has generally navigated this issue using the concept of "accompanying" acts (随伴する行為, zuihan suru kōi). Courts have consistently found that where an act of violence "accompanies" the sexual offense, even if its purpose is to escape or resist arrest, the resulting injury can form the basis of the aggravated crime. The 2008 Supreme Court case provided the first opportunity for the nation's highest court to apply this doctrine to a fleeing scenario in the modern era.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Affirming the "Accompanying Act" Doctrine

The Supreme Court upheld the lower court's decision and dismissed the appeal. In its reasoning, the Court directly addressed the defendant's central claim about his change in intent.

The Court acknowledged that X committed the violence against A after he had "lost his intent to commit an indecent act" due to her waking up and confronting him. Nonetheless, the Court concluded:

"...such violence by the defendant can be said to be accompanying the aforementioned quasi-forcible indecency, and therefore the crime of forcible indecency resulting in injury should be established for the injury to the said victim caused thereby."

This concise statement powerfully affirmed that a perpetrator's shift in subjective intent from "indecency" to "escape" does not automatically sever the legal connection between the initial crime and the subsequent injury. The violence was an "accompanying" act, and that was sufficient.

Deconstructing "Accompanying": The Two Pillars of Analysis

While the Supreme Court's decision itself is brief, legal analysis and prior case law help to illuminate the factors that underpin the "accompanying act" framework. The determination generally rests on two key pillars: the continuity of intent and temporal-spatial contiguity.

Pillar 1: Continuity of Will (意思の連続性)

The most complex aspect of the ruling is how it reconciles the finding that X's violence was "accompanying" with the simultaneous acknowledgement that his "indecent intent" was gone. The key lies in the concept of a single, unbroken chain of events driven by a continuous will.

The prevailing interpretation is that this is a question of a "single series of acts" (ichiren no kōi). In a situation like this, the indecent act provokes the victim's resistance. That resistance, in turn, directly causes the perpetrator's "indecent will" to transform into an "escape will". Because one flows immediately and causally from the other, there is a "continuity of will" that links the indecency and the subsequent violence into one criminal transaction. The will to escape is not a new, independent impulse but a direct consequence of the initial crime being discovered.

This can be contrasted with a historical case from 1926. In that case, after a rape, the perpetrator later assaulted the victim again with a new intent to coerce her into silence. The court treated this second assault as a separate crime, not as part of an aggravated rape-injury offense. The key difference is that the second violent intent was not a direct, immediate transformation of the indecent will but a new one formed after a break in the action.

Pillar 2: Temporal and Spatial Contiguity (時間的・場所的接着性)

The second pillar is the proximity in time and place between the base crime and the act causing injury. This factor provides strong evidentiary support for the conclusion that the acts are part of a single event.

In X's case, the connection was undeniable. The violence occurred immediately after the indecency was interrupted, and it happened in the very same room within the victim's home. This close temporal and spatial link was explicitly noted by the first-instance court and is considered an "extremely important" element in the analysis.

Some legal scholars view this factor less as a positive requirement and more as a potential "negative" check. In this view, close contiguity is expected in a single series of acts, but a significant gap in time or distance could serve to break the chain, even if the perpetrator's motive appears connected.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2008 decision solidified a broader interpretation of when an injury can be legally attributed to a sexual offense. It affirmed that the criminal transaction does not end at the precise moment the indecent act ceases. When a perpetrator's act of indecency is discovered and met with resistance, the ensuing struggle to flee is not a new, independent crime but an "accompanying" part of the original offense.

The ruling establishes that an injury caused during such an escape, born directly out of the victim's resistance to the sexual assault, is considered a realization of the inherent danger of the base crime. By reinforcing the long-standing "accompanying act" doctrine, the Court provided crucial guidance, confirming that the legal boundaries of a sexual assault extend to include the immediate, violent efforts to escape its consequences.