When the Board Doesn't Know: Validity of Deals by Japanese Representative Directors Lacking Internal Approval

Case: Action for Recovery of Buildings and Land, Confirmation of Ownership, and Procedures for Transfer of Registration, and Counterclaim

Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of September 22, 1965

Case Number: (O) No. 1378 of 1961

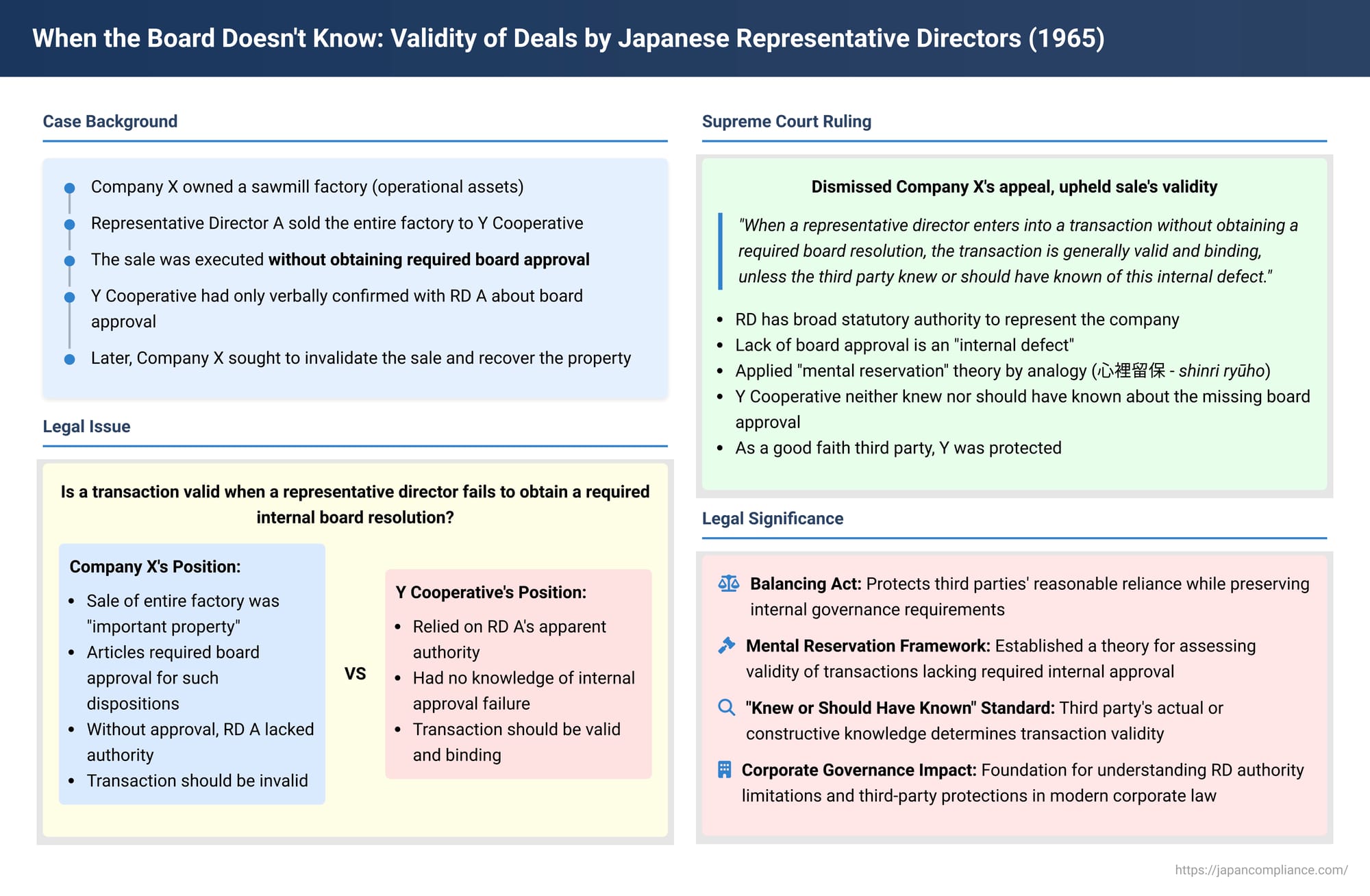

In the structure of a Japanese stock company (株式会社 - kabushiki gaisha), the representative director (代表取締役 - daihyō torishimariyaku, often abbreviated as RD) is typically vested with broad authority to act on behalf of the company in its external dealings. However, for certain significant matters, the company's internal decision-making power rests with the board of directors. This raises a critical question: what is the legal status of a transaction entered into by a representative director with a third party if the RD failed to obtain a necessary internal resolution of approval from the board? A foundational Supreme Court decision on September 22, 1965, addressed this issue, establishing a principle that seeks to balance the protection of third parties relying on the RD's apparent authority with the company's internal governance requirements, notably by drawing an analogy to the legal concept of "mental reservation."

A Sawmill Sold, A Board Bypassed: Facts of the Case

The plaintiff, Company X, was engaged in the lumber and sawmill business. It entered into a sales contract (the "Sale Agreement") to transfer its entire sawmill factory – which included land, buildings, machinery, and equipment, essentially constituting all of Company X's operational assets – to Y Cooperative (the defendant). Y Cooperative intended to use the acquired property as a lumberyard.

The Sale Agreement was concluded on behalf of Company X by its representative director, A. However, a crucial internal step was missing. Company X's articles of incorporation stipulated that "important matters" required a resolution of its board of directors. Despite the significance of selling its entire operational factory, RD A proceeded with the Sale Agreement without obtaining any such resolution from Company X's board of directors. Furthermore, no shareholders' meeting was convened to approve this transaction.

When Y Cooperative was negotiating the purchase, its due diligence regarding Company X's internal approvals was limited. It had only orally asked RD A whether the necessary board resolution for the factory transfer had been obtained; it did not undertake a more detailed investigation into the matter.

Subsequently, a dispute arose, and Company X (presumably under new circumstances or leadership) sought to invalidate the Sale Agreement and demanded that Y Cooperative return the factory property. Company X advanced several arguments for the agreement's invalidity:

- The sale of its entire factory amounted to a "transfer of business" (営業譲渡 - eigyō jōto, a concept similar to "business transfer" or 事業譲渡 - jigyō jōto under current company law). Such a fundamental transaction required a special resolution of the shareholders' meeting, which had not occurred. (The High Court later rejected this characterization, finding it was not a "transfer of business" in the legal sense that mandates a special shareholder resolution, and this point was not the primary focus of the Supreme Court's main reasoning on the board approval issue).

- Even if not a "transfer of business," the sale of the entire factory unquestionably constituted a disposition of "important property," which, under Company X's articles of incorporation (and general principles of board authority), required a resolution of the board of directors. This approval was absent.

- RD A had allegedly abused his authority in connection with the transaction, purportedly misappropriating a large portion of the sales proceeds as his own remuneration. (The High Court, in its findings, did acknowledge this abuse of authority by RD A).

Y Cooperative contested these claims, arguing that the Sale Agreement was valid and that it had legitimately acquired ownership of the factory. It filed a counterclaim seeking confirmation of the existence and validity of the Sale Agreement.

The Lower Courts' Stance: Protecting the Unknowing Buyer

Both the court of first instance (Nagano District Court, Kisofukushima Branch) and the appellate court (Tokyo High Court) ruled against Company X, dismissing its demand for the return of the property. The High Court, while finding that RD A had indeed abused his authority, focused on the lack of board approval for what it considered a disposition of important property. It concluded that Y Cooperative, the buyer, neither knew nor could reasonably have been expected to know (a standard often expressed as "knew or should have known with due care" - 知りまたは知り得べかりし - shiri matawa shiriubekarishi) about this internal failure by Company X to secure a board resolution. This lack of actual or constructive knowledge on Y Cooperative's part was deemed critical. Company X appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling: The "Mental Reservation" Analogy

The Supreme Court dismissed Company X's appeal, thereby upholding the validity of the Sale Agreement with Y Cooperative. Its reasoning provided a significant framework for analyzing transactions made by representative directors without required internal board approval:

- Representative Director's Authority and the Role of Board Resolutions: The Court acknowledged that when a company's internal decision-making authority for specific business execution matters (like the disposition of important property) is vested in the board of directors, the representative director is indeed required to act in accordance with a board resolution when representing the company in external legal acts related to such matters.

- RD's General and Broad External Authority: However, the Court immediately juxtaposed this with the broad statutory authority granted to the representative director. Under the then-Commercial Code (Article 261, Paragraph 3, and Article 78, Paragraph 1), the RD possessed the authority to perform all judicial and extra-judicial acts relating to the company's business. This grant of comprehensive authority is a cornerstone of the RD system.

- Lack of Board Resolution as an "Internal Defect": Drawing these threads together, the Supreme Court reasoned that if a representative director carries out an external transaction that objectively requires an internal board resolution, but does so without actually obtaining that resolution, the transaction primarily suffers from a lack of internal corporate decision-making.

- The General Rule – Transaction is Valid Externally: Despite this internal defect, the transaction entered into by the RD with a third party is, in principle, valid in its external effect. The RD has the apparent and general statutory authority to bind the company.

- The Exception – Third Party's Knowledge or Negligence Regarding the Internal Defect: The transaction becomes invalid only if the counterparty (the third party) knew, or reasonably should have known (i.e., was negligent in not knowing), that the necessary board resolution had not, in fact, been obtained.

- Application to the Present Case: The Supreme Court accepted the High Court's factual finding that RD A required a board resolution to sell the factory (as it was an "important matter" under Company X's articles) but failed to secure one. However, the High Court had also found that Y Cooperative (the buyer) neither actually knew about this lack of internal approval nor could it have reasonably been expected to know (i.e., Y Cooperative was not negligent in its lack of knowledge). The Supreme Court found no error in this factual assessment by the High Court.

Therefore, because Y Cooperative was, in effect, a good faith and non-negligent third party with respect to Company X's internal governance failure, the Sale Agreement was held to be valid and binding on Company X, despite the absence of the required board resolution.

Analysis and Implications: Balancing Internal Governance with Transaction Security

This 1965 Supreme Court decision was a landmark because it was the first by the highest court to clearly articulate a legal framework, often referred to by commentators as the "mental reservation" (shinri ryūho) theory by analogy, for assessing the validity of transactions entered into by a representative director who lacked a requisite internal board approval.

- The Tension: RD's External Authority vs. Board's Internal Control:

Japanese company law creates an inherent tension. The RD is granted broad statutory power to represent the company in all its business dealings (now Companies Act Article 349, Paragraph 4). This authority is generally considered "unlimitable" as against third parties who act in good faith (now Companies Act Article 349, Paragraph 5, which protects third parties who are unaware and not grossly negligent regarding restrictions on RD's authority).

Simultaneously, the board of directors is vested with the power to make decisions on important business matters, and certain critical decisions cannot be delegated away from the board (now Companies Act Article 362, Paragraph 4, which explicitly lists "disposition and acquisition of important property" as a matter for board resolution).

This case grappled with the consequences when these two principles collide: an RD with general external authority acts on an important matter without the specific internal decision of the board. - The "Mental Reservation" (心裡留保 - shinri ryūho) Analogy:

The Supreme Court's reasoning in this case is widely understood by legal scholars as drawing an analogy to the concept of "mental reservation" found in Article 93 of the Japanese Civil Code. Article 93 states that a declaration of intent is not invalidated even if the declarant makes it knowing that it does not reflect their true inner intention (mental reservation), unless the other party to whom the declaration was made knew, or should have known, of this discrepancy between the declared intent and the true intent.

In the corporate context of this Supreme Court case, the RD's act of entering into the Sale Agreement is viewed as the outward declaration of the company's intent, which appears valid given the RD's general representative authority. However, the lack of the internal board resolution signifies that the company's "true collective intent" (as should have been formed by the board) to enter into this specific transaction was absent.

Following the analogy, the RD's transaction (the outward declaration) is held to be valid, binding the company, unless the third-party counterparty knew or was negligent in not knowing that the company's "true intent" (i.e., the necessary internal board approval) was missing. - Critiques of the "Mental Reservation" Analogy:

Many legal scholars have found this analogy to be somewhat artificial or strained. A key criticism is that, unlike a typical mental reservation scenario where the declarant consciously misrepresents their intent, a representative director usually does intend for the company to be bound by the transaction they are concluding, even if they are aware they are bypassing an internal approval process. The analogy, therefore, focuses more on the "company's lack of true (collective) intent" due to the missing board decision, rather than a mental reservation on the part of the RD themselves. - Alternative Theoretical Frameworks:

While the Supreme Court adopted this "mental reservation" approach, other legal theories could also be considered:- Abuse of Authority (権限濫用 - kengen ran'yō): If a representative director acts for their own personal benefit or in a way that is clearly detrimental to the company's interests, even if the act is within the general scope of their authority, it can be deemed an abuse of that authority. Transactions resulting from such abuse are often held to be invalid against third parties who knew or should have known of the director's improper purpose. The High Court in this case did find that RD A had abused his authority by misappropriating sales proceeds. The Supreme Court's "mental reservation" approach to the lack of board approval might be seen as having a similar protective effect for good-faith third parties as the abuse of authority doctrine often does.

- Scope of Representative Authority and Statutory Restrictions: A more modern and widely supported view, particularly under the current Companies Act, is to consider provisions like Article 362, Paragraph 4 (which lists matters requiring a board resolution, such as the disposition of important property) as directly imposing a limitation on the representative director's authority for those specific types of transactions. If an RD acts without board approval on such a matter, they are acting beyond their actual authority. In such cases, the validity of the transaction with a third party would then be determined by Article 349, Paragraph 5 of the Companies Act. This article protects a "third party in good faith" (which is generally interpreted as meaning a third party who was unaware of the restriction on the RD's authority and was not grossly negligent in being unaware). This approach tends to lead to a "good faith and no gross negligence" standard for the third party, which some see as more aligned with other areas of corporate law than the "knew or should have known" (simple negligence) standard arguably implied by the strict mental reservation analogy.

- The "Knew or Should Have Known" Standard:

The Supreme Court's threshold for invalidating the transaction – that the third party "knew or reasonably should have known" about the lack of board approval – implies a negligence standard for the third party. If a reasonably prudent third party, under the circumstances, would have made inquiries that would have revealed the lack of internal approval, their failure to do so could render the transaction voidable by the company. The application of this standard by courts has varied over time, sometimes appearing relatively strict on third parties, other times more lenient. There remains an ongoing discussion in legal scholarship about whether this standard should be interpreted as requiring the absence of simple negligence or the absence of gross negligence to align it more consistently with other third-party protection rules in company law. - Who Can Assert Invalidity?

While this case involved the company (Company X) itself trying to assert the invalidity of the transaction, a subsequent Supreme Court decision in 2009 (concerning a different but related issue of RD authority) clarified that, generally, only the company can assert the invalidity of a transaction due to a lack of internal board approval. Third parties (for example, a debtor whose debt was assigned by an RD without board approval) usually cannot raise this internal corporate defect as a defense, unless special circumstances exist (such as the company itself having already decided to repudiate the transaction). - Historical Context:

It's noteworthy that this 1965 Supreme Court decision was rendered before the "disposition of important property" was explicitly listed as a matter requiring a board resolution in the text of the Commercial Code itself (this explicit statutory listing came with the 1981 revision of the Commercial Code). At the time of this case, the requirement for Company X's board to approve such a significant sale would have stemmed either from its own articles of incorporation or from general principles of corporate law regarding the board's authority over fundamental corporate matters. The Supreme Court's application of the "mental reservation" theory in this context set a precedent for how to deal with a lack of internal authorization, regardless of whether that authorization was mandated by statute or by the company's own internal rules.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment of September 22, 1965, established a foundational principle in Japanese corporate law: when a representative director enters into a transaction with a third party that requires, but lacks, an internal board of directors' resolution, the transaction is generally considered valid and binding on the company. It can only be invalidated by the company against the third party if that third party knew, or was negligent in not knowing (i.e., "should have known"), that the necessary internal approval was missing.

By drawing an analogy to the Civil Code concept of "mental reservation," the Supreme Court prioritized the safety and predictability of external commercial transactions, ensuring that third parties dealing in good faith with a company's representative director are not unduly prejudiced by internal corporate governance failings of which they are reasonably unaware. While the specific legal theory underlying this approach (the "mental reservation" analogy) has been subject to academic debate and refinement over the years, its practical effect of protecting reasonably reliant third parties while still holding RDs accountable internally has been an influential tenet of Japanese corporate law.