When Talk Turns to Trouble: Antitrust Risks of Information Exchange in Japan – Lessons from the Shutter Cartel Case

TL;DR

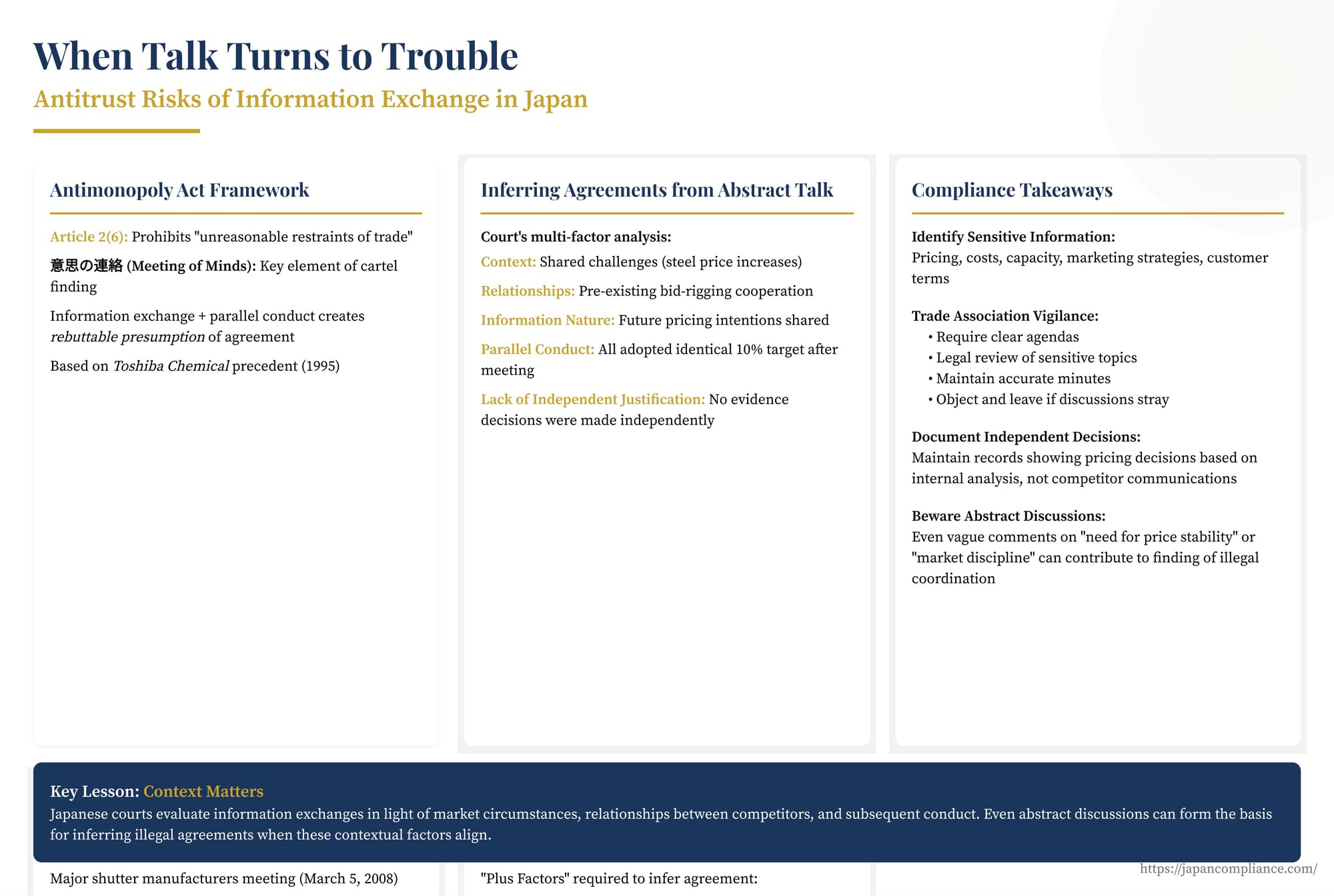

- Japan’s Antimonopoly Act infers a cartel when competitors share sensitive future data (prices, output) and later act in parallel.

- The 2023 Tokyo High Court “Shutter cartel” ruling confirmed that even vague talk of a “10 % increase” plus subsequent aligned price hikes showed a meeting of minds.

- Firms must police trade-association talks, ban pricing chatter and document independent decision-making to avoid JFTC surcharges and criminal exposure.

Table of Contents

- Information Exchange and Inferring Agreements under the AMA

- The Shutter Cartel Case: Background (Tokyo High Court, April 7 2023)

- Inferring Price-Fixing from "Abstract" Information Exchange

- Comparison with US Antitrust Standards

- Compliance Takeaways for Businesses Operating in Japan

- Conclusion

Exchanging information with competitors can be a tightrope walk under antitrust laws worldwide. While some sharing, particularly within legitimate trade association activities, can be benign or even procompetitive, discussions involving competitively sensitive topics like pricing, costs, output, or strategic plans can easily cross the line into illegal collusion. Proving an explicit agreement to fix prices or rig bids can be challenging for authorities, making the analysis of information exchange and subsequent market behavior crucial.

Japan's Antimonopoly Act (AMA) strictly prohibits "unreasonable restraints of trade" (不当な取引制限 - futō na torihiki seigen), which includes cartels like price-fixing and bid-rigging. A key element is establishing a "meeting of minds" (意思の連絡 - ishi no renraku) among competitors to coordinate their actions. This doesn't necessarily require a formal contract; Japanese antitrust authorities and courts can, and often do, infer the existence of such an understanding from circumstantial evidence. A recent Tokyo High Court decision involving major shutter manufacturers highlights how even seemingly abstract discussions among competitors can lead to findings of illegal collusion when viewed in context.

Information Exchange and Inferring Agreements under the AMA

Article 2(6) of the AMA defines an unreasonable restraint of trade as business activities where undertakings mutually restrict or conduct their business activities in concert with other undertakings, thereby substantially restraining competition in a particular field of trade contrary to the public interest. The cornerstone is the mutual understanding or "meeting of minds" (ishi no renraku) to coordinate competitive behavior.

Direct evidence of such an agreement (like a signed contract or explicit communication) is often absent in cartel cases. Consequently, the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) and courts rely heavily on indirect evidence. A well-established principle in Japanese antitrust jurisprudence, stemming from landmark cases like Toshiba Chemical (Tokyo High Court, September 25, 1995), holds that:

- Where competitors exchange information concerning competitively sensitive matters (especially future pricing or output intentions), and

- Subsequently engage in parallel conduct consistent with that exchange (e.g., uniform price increases),

- A rebuttable presumption arises that there was a "meeting of minds" (ishi no renraku) to coordinate this conduct.

The burden then shifts to the companies to demonstrate that their parallel actions were the result of independent business decisions based on market conditions, rather than coordination stemming from the information exchange. Simply pointing to shared external factors (like rising input costs) may not be sufficient if the timing and nature of the parallel conduct align closely with the specific information exchanged.

The Shutter Cartel Case: Background (Tokyo High Court, April 7, 2023)

The case involved cease-and-desist orders and significant surcharge payment orders issued by the JFTC against major Japanese shutter manufacturers: Sanwa Shutter Corp. (三和シヤッター工業), Bunka Shutter Co., Ltd. (文化シヤッター), Toyo Shutter Co., Ltd. (東洋シヤッター), and (for one part of the case) Sanwa Holdings Corp. (三和ホールディングス).

The JFTC found two distinct violations under AMA Article 2(6):

- The "Kinki Agreement": From at least May 2007, the four companies engaged in bid-rigging for specific shutter products ordered by construction companies in the Kinki (近畿) region, essentially deciding amongst themselves who would win particular bids.

- The "National Agreement": Around March 5, 2008, executives from Sanwa Shutter, Bunka Shutter, and Toyo Shutter met and reached an understanding to raise their sales prices for specific shutter products nationwide by approximately 10%, starting with quotes issued from April 1, 2008.

The companies challenged the JFTC's findings, particularly regarding the National Agreement, arguing the evidence of a "meeting of minds" was insufficient. The Tokyo High Court, in its decision on April 7, 2023 (Case Nos. 2020 [Gyo-Ke] 10-12), ultimately upheld the JFTC's decision on both agreements. The court's analysis regarding the inference of the National Agreement from information exchange is particularly instructive.

Inferring Price-Fixing from "Abstract" Information Exchange

The evidence underpinning the finding of the National price-fixing agreement centered on the March 5, 2008 meeting between high-level executives of the three main shutter companies. The specific content of the discussion, as reconstructed by the JFTC and accepted by the court, appeared somewhat general or abstract:

- One executive reportedly stated something to the effect of, "We need about a 10 percent [increase]," with another agreeing, "Yes, that's right."

- There was a comment about needing to raise prices presented in quotations to customers.

- There was discussion regarding the fact that Sanwa Shutter and Bunka Shutter were planning to publicly announce price increases soon.

The companies argued that such abstract conversation did not amount to a concrete agreement to fix prices. However, the Tokyo High Court disagreed, finding that the JFTC had sufficient grounds to infer a "meeting of minds" when considering the exchange in light of several key contextual factors and subsequent actions:

- Context, Motive, and Pre-existing Relationships:

- Shared Challenges: All three companies faced identical market pressures – demands from general contractors (customers) for lower prices and significant increases in the cost of steel (a major input), particularly an anticipated major hike from April 2008. This provided a strong common motive to raise prices.

- Timing: The meeting occurred precisely when the companies were individually contemplating price increases due to the imminent steel cost surge.

- Established Cooperation: Crucially, the companies were not just competitors; they were already engaged in coordinated activity through the Kinki bid-rigging scheme. Furthermore, they were reportedly initiating discussions for similar coordination in the Kanto region, led by the same executives present at the March 5th meeting. This pre-existing cooperative relationship fostered the mutual understanding and trust necessary to facilitate a coordinated price increase.

- Nature of Information Exchanged:

- Competitively Sensitive: While perhaps not explicitly stating "Let's agree to raise prices by exactly 10%," the discussion touched upon core competitive parameters: the magnitude of the desired increase ("about 10 percent"), the method (raising quoted prices), and implicitly, coordination/timing (referencing planned public announcements).

- Beyond Public Knowledge: This exchange involved sharing internal considerations and future intentions – information companies would normally keep confidential from competitors in a truly competitive environment. The court viewed this sharing of sensitive internal perspectives as indicative of an underlying understanding.

- Subsequent Parallel Conduct:

- Shift After Meeting: The court noted evidence suggesting that prior to the March 5th meeting, none of the three companies had definitively settled internally on a specific 10% price increase target.

- Convergence on 10%: Following the meeting, however, all three companies successively adopted the 10% figure (matching the level discussed) as their internal target for the price increase and issued instructions to their respective sales offices to implement it from April 1st.

- Alignment with Discussion: This parallel adoption of the specific 10% target, closely following the meeting where that figure was discussed, was seen as behavior conforming to an inferred agreement, not mere coincidence.

- Lack of Independent Justification:

- The court found no compelling "special circumstances" to suggest that the companies' decisions to target a 10% increase immediately after the meeting were made independently of each other or the discussion. While rising steel costs provided a general reason to raise prices, it didn't explain the specific convergence on the 10% figure at that particular time.

Therefore, the High Court concluded that the combination of the context (shared motive, existing cooperation), the nature of the information exchanged (sensitive future intentions), and the subsequent, closely aligned parallel conduct provided substantial evidence to infer a "meeting of minds" – an illegal price-fixing agreement under the AMA. The abstract nature of the conversation alone did not preclude this finding when viewed holistically with the surrounding circumstances.

Comparison with US Antitrust Standards

The Japanese approach to inferring agreements from information exchange bears comparison to US law under Section 1 of the Sherman Act. US courts also rely on circumstantial evidence to prove conspiracies, as direct evidence is often unavailable.

- Parallel Conduct Alone is Insufficient: Like in Japan, US law holds that mere parallel conduct among competitors (e.g., parallel price increases) is not, by itself, enough to establish an illegal agreement. Such conduct could equally be the result of independent responses to common market conditions (conscious parallelism).

- "Plus Factors": To infer a conspiracy from parallel conduct, US plaintiffs must typically present additional evidence – "plus factors" – that tends to exclude the possibility of independent action. These plus factors can include:

- Actions taken by firms that would be against their self-interest unless competitors also acted similarly.

- Evidence of specific types of information exchange, particularly regarding future prices or output intentions.

- The presence of mechanisms for monitoring or enforcing adherence to a potential agreement.

- A historical context of collusion in the industry.

- The complexity or artificiality of the parallel conduct.

- Information Exchange Analysis: The exchange of competitively sensitive information, especially future pricing data, is a significant plus factor in the US. However, US courts generally do not apply a formal rebuttable presumption like the one derived from Japan's Toshiba Chemical case. Instead, the information exchange is weighed alongside other evidence (parallel conduct and other plus factors) to determine if an inference of agreement is warranted under the totality of the circumstances. The focus is on whether the evidence, taken as a whole, makes the existence of an agreement more likely than not and tends to rule out independent action.

While both systems analyze context, the nature of information, and parallel behavior, the Japanese framework, particularly the potential presumption arising from exchange followed by parallelism, might arguably present a somewhat different analytical pathway than the US "plus factor" approach, although the practical outcomes in clear cases might often be similar.

Compliance Takeaways for Businesses Operating in Japan

The Shutter case serves as a potent reminder of the antitrust risks associated with competitor communications in Japan. Even seemingly informal or high-level discussions can form the basis for inferring an illegal agreement if other circumstantial factors align. To mitigate these risks, companies (including US firms operating in Japan) should implement robust compliance measures:

- Identify Sensitive Information: Clearly define what constitutes competitively sensitive information for your business – this typically includes current and future pricing, discounts, costs, production levels, capacity plans, marketing strategies, specific customer information, and terms of sale.

- Strict Communication Protocols: Establish clear rules prohibiting employees from discussing sensitive topics with competitors, whether directly, through intermediaries, or at industry gatherings. This includes avoiding informal "off-the-record" conversations.

- Trade Association Vigilance:

- Ensure participation in trade associations adheres to strict antitrust guidelines.

- Insist on clear agendas circulated in advance, avoiding sensitive topics.

- Have legal counsel review agendas and attend meetings whenever sensitive topics might arise.

- Keep accurate minutes, and object on the record (and leave, if necessary) if discussions stray into prohibited areas.

- Avoid participation in unsupervised data exchanges, especially concerning future plans or individual company data.

- Beware of Abstract Discussions: The Shutter case demonstrates that danger lies not only in explicit agreements but also in discussions that facilitate coordinated conduct. Avoid conversations that could be interpreted as signaling future intentions or reaching a common understanding on competitive parameters, even if vague (e.g., "prices need to go up significantly," "we should aim for stability").

- Document Independent Decision-Making: Maintain thorough internal documentation justifying key commercial decisions (especially pricing changes). This documentation should demonstrate that decisions were based on independent analysis of market conditions, costs, and company strategy, not on communications with competitors. This is particularly important if your actions happen to parallel those of competitors.

- Regular Antitrust Training: Conduct periodic, practical antitrust training for all employees who interact with competitors or participate in industry associations, emphasizing the risks of information exchange.

Conclusion

The Tokyo High Court's decision in the Shutter cartel case underscores the JFTC's and Japanese courts' commitment to combating cartels, even when direct evidence of an agreement is lacking. The ruling reaffirms that a "meeting of minds" (ishi no renraku) can be inferred from a combination of circumstantial factors, with the exchange of competitively sensitive information – even if seemingly abstract – playing a pivotal role when viewed alongside market context and subsequent parallel behavior. For businesses operating in Japan, this highlights the critical importance of maintaining strict discipline in competitor communications and ensuring that all commercial decisions are, and can be documented as, independently determined. Robust compliance programs and ongoing employee education are essential safeguards against inadvertently crossing the line into an unreasonable restraint of trade under the Japanese Antimonopoly Act.

- Fair Dealings in Japan: Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position and the Oshigami Case

- Antitrust Enforcement in Japan’s Liberalized Energy Markets: Lessons from Recent Cartel and Collusion Cases

- Antitrust Alert: Lessons from Japan's Fisheries Cooperative Case on Exclusive Dealing

- JFTC – Guidelines on Information Exchange Between Competitors (Japanese)

- JFTC – 2023 Shutter Cartel Press Release (Japanese)