When Self-Defense Ends and Assault Begins: A 2008 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Decision Date: June 25, 2008

The law of self-defense protects the right of an individual to use force against an imminent threat. But this right is not a blank check. The doctrine of excessive self-defense exists to address situations where a person, acting defensively, uses more force than necessary. A particularly complex question arises when the defensive action continues after the threat has been neutralized. Is this entire sequence one continuous act of "excessive self-defense," or does it split into two legally distinct events: a justified defense followed by an unjustified assault?

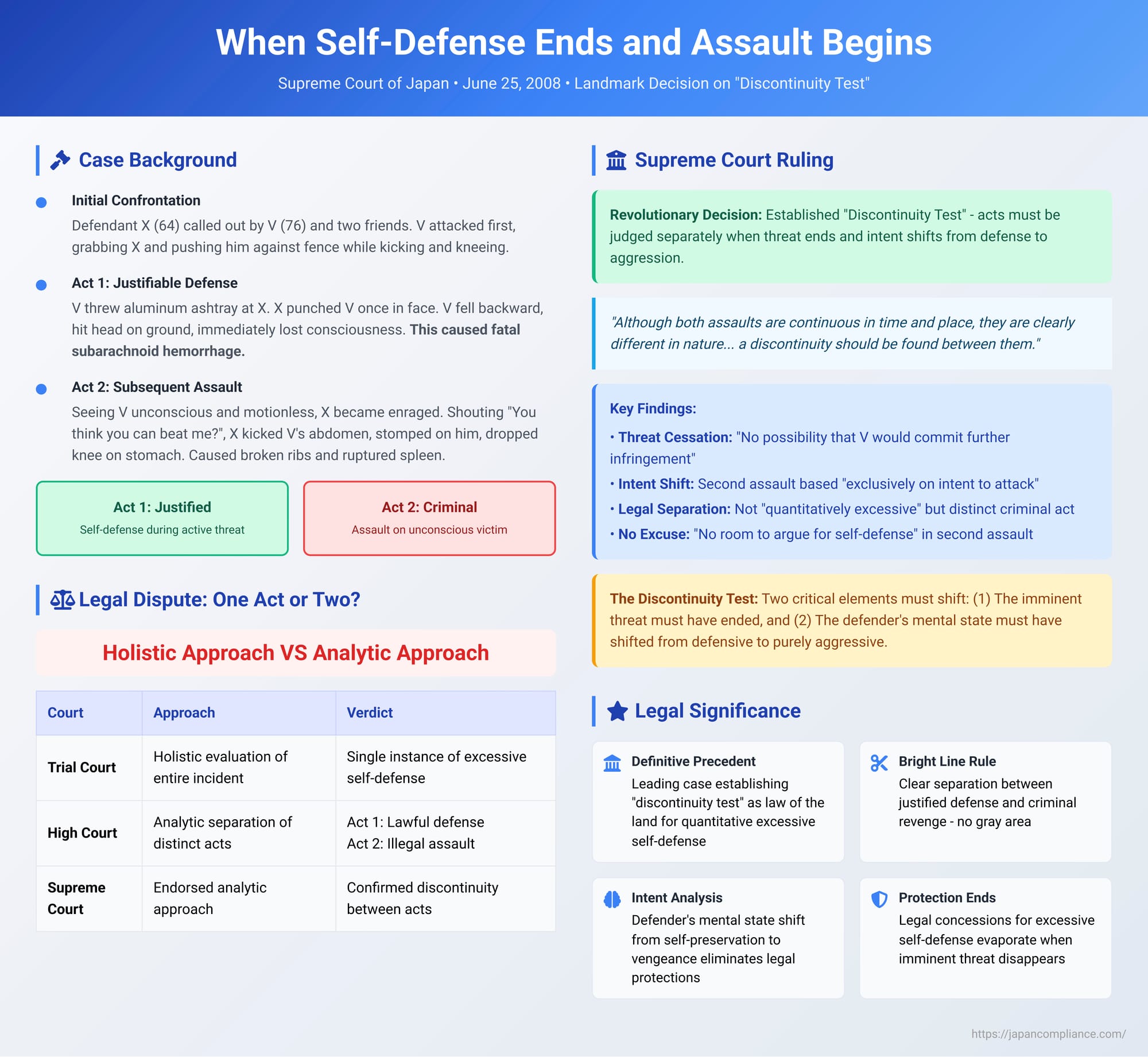

On June 25, 2008, the Supreme Court of Japan issued a landmark decision that provided a clear and powerful answer to this question. The case involved a violent altercation where the defendant, after successfully felling his attacker in a justifiable act of self-defense, proceeded to viciously beat the now-unconscious man. In its ruling, the Court established a crucial "discontinuity" test for separating a legitimate defensive act from a subsequent criminal assault, drawing a bright line between self-preservation and revenge.

The Factual Background: A Confrontation in Two Acts

The incident began when the defendant, X (then 64 years old), was called out by an acquaintance, V (then 76 years old), who was accompanied by two friends, A and B. X, who had been subjected to unprovoked assaults by V in the past, agreed to speak with him.

The confrontation quickly escalated into a physical brawl. V attacked X without warning, grabbing him and pushing him against a fence while kicking and kneeing him. X, seeing V's friends approaching and fearing a three-on-one attack, shouted "I'm yakuza!" in an attempt to intimidate them. The fight continued, culminating in a sequence of two distinct "acts" of violence by the defendant.

Act 1: The Justifiable Defense

As the two men grappled, V picked up a large, cylindrical aluminum ashtray and threw it at X. X dodged the ashtray. As V was off-balance from the throw, X punched him once in the face. This single punch caused V to fall backward, strike his head on the tiled ground, and immediately lose consciousness, lying motionless on his back. Critically, this first act of violence—the single punch and resulting fall—was the cause of V's subsequent death from a subarachnoid hemorrhage due to a skull fracture.

Act 2: The Subsequent Assault

Seeing V lying on the ground, unconscious and unmoving, X became enraged. He was fully aware that V was incapacitated. Shouting, "You think you can mess with me? You think you can beat me?", X proceeded to launch a second, vicious assault on the helpless man. He kicked V's abdomen, stomped on him, and dropped his knee onto his stomach. This second assault caused additional, non-fatal injuries, including broken ribs and a ruptured spleen.

The Journey Through the Courts: One Act or Two?

The central legal question was how to evaluate this sequence of events. Was it a single, continuous act of excessive self-defense, or was it two separate acts with different legal characters?

- The Trial Court: A "Holistic" Finding of Excessive Self-Defense. The first-instance court found that the first assault was a legitimate act of self-defense, but the second assault occurred after the threat from V had ended and was driven purely by an intent to harm. However, the court then chose to perform a "holistic evaluation" of the entire incident. It bundled both acts together and concluded that, as a whole, they constituted a single instance of excessive self-defense, convicting the defendant of the crime of Injury Resulting in Death.

- The High Court: An "Analytic" Finding of Separate Acts. The appellate court disagreed with the trial court's methodology. While it also found that the first assault was justifiable self-defense and the second was not, it rejected the "holistic" approach. The High Court ruled that the two acts were "clearly different in nature" and that there was a legal "discontinuity" between them. The threat from V had ceased, and the defendant's intent had shifted from defense to pure aggression. Therefore, the acts had to be analyzed separately. This led to a startling conclusion:

- The first assault, which caused the fatal injury, was lawful self-defense. Therefore, X was not criminally responsible for V's death.

- The second assault was a separate and illegal act of violence.

The High Court overturned the conviction for Injury Resulting in Death and instead convicted X only of the lesser crime of Injury for the second assault.

The defendant's counsel appealed, arguing for a return to the trial court's holistic approach, which would frame the entire event under the umbrella of self-defense.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Ruling: The "Discontinuity" Test

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal and fully endorsed the High Court's analytical approach, cementing the "discontinuity" test as the law of the land for such cases.

The Court's reasoning was clear and direct. It first affirmed the factual basis: after the first assault, there was "no possibility that V would commit a further act of infringement against the defendant." The defendant "was fully aware of this." His second assault was therefore based "exclusively on an intent to attack," and as such, "it is clear that the second assault does not satisfy the requirements for self-defense."

The Court then explained why the two acts could not be bundled together:

"Although both assaults are continuous in time and place, they are clearly different in nature with respect to the continuity of the infringement by V and the existence of an intent to defend on the part of the defendant... a discontinuity should be found between them. It cannot be recognized as a case in which, in the course of continuing a counter-attack against an imminent and unjust attack, the counter-attack became quantitatively excessive."

Therefore, the Court concluded, it was "not appropriate to consider both assaults holistically and find a single instance of excessive self-defense." The acts must be judged separately. The first assault was justifiable self-defense and not a crime. The second assault was a crime of injury, with "no room to argue for self-defense, let alone excessive self-defense."

A Deeper Dive: The Legal Theory of "Quantitative Excessive Self-Defense"

This case is the leading Japanese precedent on what is known as "quantitative excessive self-defense" (ryōteki kajō bōei). This is distinct from the more common "qualitative" excess, where a defender uses a disproportionate level of force (e.g., a deadly weapon against an unarmed attacker) against an ongoing threat. Quantitative excess, by contrast, deals with continuing an attack after the threat has ceased.

The Supreme Court's 2008 ruling resolves the long-standing debate between two methods of analysis for these cases:

- The Holistic Approach: This method, often used in older precedents, views the entire confrontation as a single, unbroken event. If the initial action was defensive, the entire sequence is evaluated under the rubric of self-defense, often leading to a finding of excessive self-defense for the later parts of the attack.

- The Analytic Approach: This method, which the Supreme Court championed in this case, dissects the confrontation into legally distinct phases. It assesses the legality of each phase based on the specific circumstances present at that moment.

The Court's "discontinuity" test provides the key for determining when an analytic approach is required. A continuous event is legally severed into two parts when there is a clear shift in two critical elements:

- The Threat: The imminent threat from the aggressor must have ended.

- The Defender's Intent: The defender's mental state must have shifted from a defensive one to a purely aggressive one.

In this case, V being knocked unconscious marked the definitive end of the threat. The defendant's own enraged shouts ("You think you can beat me?") provided powerful evidence of his shift in intent from self-preservation to vengeful punishment.

The theoretical justification for this approach is that the legal concession for excessive self-defense—a potential reduction or waiver of punishment—is based on the idea that the defender acted under the extreme psychological pressure, excitement, or confusion of an ongoing attack. Once that attack has clearly ended and the defender is no longer under such duress, the rationale for this legal concession disappears. A calculated or rage-fueled attack on a now-helpless person, even one who was the initial aggressor, is simply a new assault, not a continuation of a defensive act.

Conclusion: A Bright Line Between Defense and Revenge

The 2008 Supreme Court decision provides a clear and essential framework for courts, prosecutors, and defenders when analyzing complex and violent confrontations. It establishes the "discontinuity" test as the definitive method for distinguishing between a single, continuous act of excessive self-defense and a justifiable defense followed by a separate, illegal assault.

The ruling draws a bright and crucial line in the sand. The legal protections of self-defense, even the mitigated protections afforded to excessive defense, evaporate the moment the imminent threat disappears. An attack on a neutralized aggressor, no matter how blameworthy their prior conduct may have been, is not a continuation of defense. It is a new act of violence, born not of fear, but of revenge—and for that, the law offers no excuse.