When Rules Go Too Far: Japan's Supreme Court on Invalidating Prison Regulations

A Third Petty Bench Ruling from July 9, 1991

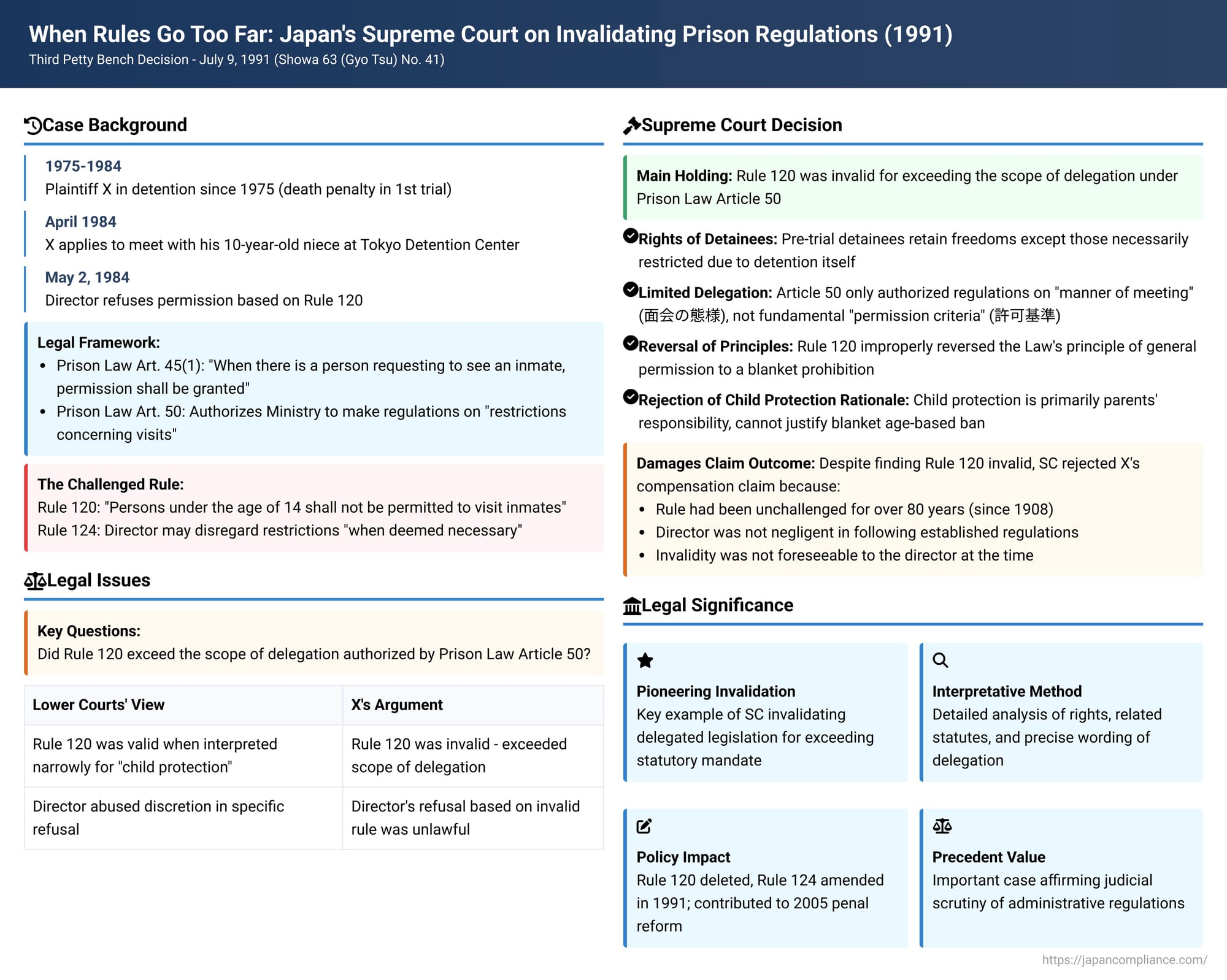

Modern governance relies heavily on "delegated legislation"—where primary laws enacted by the legislature empower executive bodies to make more detailed rules and regulations. This is often necessary for practical reasons, allowing for flexibility and technical expertise. However, a fundamental principle of the rule of law is that such administrative regulations must remain strictly within the boundaries set by the parent statute. A significant decision by the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on July 9, 1991 (Showa 63 (Gyo Tsu) No. 41), addressed this critical issue, ultimately invalidating a long-standing prison regulation concerning a detainee's right to receive visitors, specifically children.

The Facts: A Detainee, A Niece, and A Refused Visit

The plaintiff, X, had been indicted for serious offenses, including violations of the Explosives Control Act, and had been held in pre-trial detention at the Tokyo Detention Center since July 1975. He had already received a death sentence in his first trial, and his appeal against that sentence had been dismissed by the appellate court.

In April 1984, X applied to the director of the Tokyo Detention Center for permission to meet with his niece by marriage (his adoptive mother's granddaughter), who was 10 years old at the time. On May 2, 1984, the detention center director refused this request. The refusal was based on Rule 120 of the then-operative Prison Law Enforcement Regulations (旧監獄法施行規則 - Kyū Kangoku-hō Shikō Kisoku, hereinafter "the Regulations").

The Challenged Regulation: A Ban on Young Visitors

The legal framework governing visits to detainees at the time was based on the old Prison Law (旧監獄法 - Kyū Kangoku-hō, hereinafter "the Law") and the Regulations made under it:

- Prison Law, Article 45(1): This provision stated, "When there is a person requesting to see an inmate, permission shall be granted". This established a general principle of allowing visits.

- Prison Law, Article 50: This article provided the authority for delegated legislation. It stated, "Restrictions concerning the presence of an official during a visit... and other restrictions concerning visits... shall be determined by order (命令ヲ以テ之ヲ定ム)". This "order" referred to a Ministry of Justice Ordinance, which took the form of the Regulations.

- Prison Law Enforcement Regulations, Rule 120 (old version): This rule stipulated, "Persons under the age of 14 shall not be permitted to visit inmates". This created a near-blanket ban on visits by young children.

- Prison Law Enforcement Regulations, Rule 124 (old version): This rule provided a narrow exception, stating, "When the director deems it necessary for treatment or other reasons, the restrictions of the preceding four articles [which included Rule 120] may be disregarded".

The Legal Battle: Scope of Delegation and Abuse of Discretion

X filed a lawsuit against the State (Y), seeking damages under Article 1(1) of the State Compensation Act. He argued two main points:

- Rule 120 of the Regulations was itself illegal because it exceeded the scope of the rule-making authority delegated by Article 50 of the Prison Law.

- Alternatively, even if Rule 120 were deemed legal, the detention center director's refusal of this specific meeting constituted an abuse of discretion and was therefore unlawful.

The Tokyo District Court (first instance) and the Tokyo High Court (second instance) took a nuanced approach. They found Rule 120 (when read together with the discretionary exception in Rule 124) to be legal, but only by applying a restrictive interpretation. They reasoned that the purpose of these rules was the "protection of the emotional well-being of young children," and that they should be interpreted as allowing restrictions on visits only to the extent necessary to avoid concrete harm to this objective in specific cases. Despite finding the rule itself (under this interpretation) lawful, both lower courts concluded that the specific refusal of X's meeting request was an abuse of the director's discretion and was negligent, and they awarded X damages. The State then appealed this finding of liability to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision of July 9, 1991

The Supreme Court overturned the lower courts' finding of liability against the State. While the Supreme Court agreed with the ultimate conclusion that the refusal to permit the visit was unlawful, its reasoning was fundamentally different: it found that Rule 120 itself was invalid. However, it concluded that the director was not negligent in applying this long-standing (though invalid) rule, and therefore, X's claim for damages was dismissed.

Invalidity of Rule 120:

The Court's reasoning for declaring Rule 120 invalid was as follows:

- Rights of Detainees: The Court began by affirming a general principle regarding pre-trial detainees: they are, in principle, guaranteed the same freedoms as ordinary citizens, except for such restrictions as are inherently necessary due to the detention itself (e.g., restrictions to prevent escape or the destruction of evidence, or those necessary to maintain discipline and order within the detention facility). This principle had been established in previous Supreme Court precedents.

- Interpretation of Prison Law Article 45 (The Right to Visits): Article 45(1) of the Prison Law ("When there is a person requesting to see an inmate, permission shall be granted") establishes a principle of general permission for visits between detainees and external persons. This principle is further supported by Article 80 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, which states that a detained defendant may meet with persons other than their counsel within the scope of the law. Restrictions on this general right to visits are exceptional and can only be imposed for specific, legitimate reasons: (a) to the necessary and reasonable extent to prevent the detainee's escape or the destruction of evidence, or (b) to the necessary extent to prevent disturbances to prison discipline or order where there is a considerable and probable risk of such disturbances occurring. Importantly, the Court stated that this general principle of allowing visits applies even if the person requesting the visit is a young child.

- Interpretation of Prison Law Article 50 (The Scope of Delegation): Article 50 of the Prison Law delegated to an "order" (which became the Ministry of Justice's Regulations) the power to set restrictions only concerning the "manner/mode of meeting" (面会の態様 - menkai no taiyō). Examples given included the presence of an official during the visit, the location, time, and frequency of visits. Crucially, the Supreme Court held that Article 50 did not permit the Regulations to alter the fundamental "permission criteria" (許可基準 - kyoka kijun) for visits that were established by Article 45 of the Law itself.

- Rule 120 Exceeded Delegated Authority: The Court found that Rule 120 was fundamentally different in nature from other rules (such as Rules 121 to 128) that dealt with the manner or mode of visits. Rule 120, by stating "Persons under the age of 14 shall not be permitted to visit inmates," imposed a general prohibition on visits between detainees and young children. Rule 124 then allowed only limited exceptions to this prohibition at the director's discretion. This, the Court concluded, effectively reversed the Prison Law's principle of general permission for visits and instead established a general prohibition with narrow exceptions for a specific category of visitors. This amounted to a change in the fundamental permission criteria, not merely a regulation of the manner of visits.

- Rejection of Child Protection Rationale and Lower Courts' Interpretation: The Court acknowledged that Rule 120 might have been established out of a desire to protect the emotional well-being of young children who might be adversely affected by visiting a detention facility. However, it stated that these rules, by not being directly based on a statutory provision authorizing such a sweeping prohibition, significantly restricted the detainee's freedom of visitation and therefore exceeded the scope of rule-making authority delegated by Prison Law Article 50. The Supreme Court explicitly rejected the lower courts' attempt to save Rule 120 through a limiting interpretation. It reasoned that since detainees retain the general freedoms of citizens (outside those restrictions inherent to their confinement), and since the protection of a child's emotional well-being is primarily the responsibility of their parents or legal guardians, the Prison Law itself could not be interpreted as intending or permitting a blanket, across-the-board ban on visits between detainees and young children solely based on the visitor's age.

Therefore, Rule 120 (and Rule 124 insofar as it created exceptions to this invalid prohibition) was deemed invalid for exceeding the scope of delegation under Article 50 of the Prison Law, even if one tried to apply a restrictive interpretation to it.

Since Rule 120 was invalid, and there were no findings in this case that X's meeting with his 10-year-old niece would pose any risk of escape, destruction of evidence, or disruption of prison order, the detention center director should have permitted the visit in accordance with the principle in Prison Law Article 45. The refusal was, therefore, unlawful.

"Exceeding the Scope of Delegation" (委任の範囲の逸脱 - Inin no Hani no Itsudatsu)

This case is a clear illustration of the legal doctrine of inin no hani no itsudatsu, or "exceeding the scope of delegation." This principle dictates that when a legislature (like the National Diet) delegates authority to an executive body to make detailed rules (like the Ministry of Justice issuing the Prison Law Enforcement Regulations), those rules must:

- Be consistent with the parent statute.

- Not contradict the provisions or the fundamental principles of the parent statute.

- Not unduly expand upon the authority granted by the parent statute.

If a regulation fails these tests, it can be declared null and void by the courts, as happened with Rule 120 in this instance. This case focused squarely on the content of the delegated legislation being incompatible with the limits set by the delegating statute.

No Negligence, No Compensation Despite Unlawful Act

Despite finding the director's refusal unlawful because it was based on an invalid rule, the Supreme Court ultimately denied X's claim for State compensation. The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Rule 120 (and its related provisions) had been promulgated in 1908 (Meiji 41) and had remained in effect for over 80 years without its validity being seriously questioned in administrative practice or successfully challenged in court until this very case.

- In fact, both the District Court and the High Court in X's lawsuit had initially upheld the validity of Rule 120 (through restrictive interpretation).

- Given this long history and the lack of prior successful challenges, it could not be said that the invalidity of Rule 120 was easily foreseeable by the detention center director at the time of the refusal.

- A public official, like the prison director, has a duty to carry out their functions in accordance with existing laws and regulations. Since the director acted in accordance with the long-standing Rule 120, it could not be concluded that the director was "negligent" (過失 - kashitsu) in the sense required by Article 1(1) of the State Compensation Act, even though the rule itself was later found to be invalid by the Supreme Court.

Thus, while the act of refusal was based on an invalid rule and was therefore unlawful, the lack of foreseeability of the rule's invalidity meant the director's conduct did not meet the "negligence" threshold for state compensation.

Significance and Impact of the Ruling

This 1991 Supreme Court decision is considered a landmark for several reasons:

- Pioneering Invalidation of Delegated Legislation: It stands as a key example of the Supreme Court exercising its power to invalidate a piece of delegated legislation (a ministry ordinance) for exceeding the scope of its statutory mandate. It reinforced the principle that administrative rules are subordinate to laws passed by the Diet.

- Meticulous Interpretative Method: The Court engaged in a detailed and careful interpretation of the relevant legal provisions, examining the nature of the rights at stake (a detainee's freedom to receive visitors), related statutes (like the Code of Criminal Procedure), and, crucially, the precise wording and intent of the delegating provision in the parent Prison Law (Article 50, which focused on the "manner of meeting" rather than the fundamental right to meet).

- Significant Impact on Penal Policy: The judgment had a direct and substantial impact on penal policy and practice in Japan. Following this decision, Rule 120 was deleted from the Prison Law Enforcement Regulations, and Rule 124 was amended in 1991. This ruling also contributed to the broader momentum for reforming the treatment of detainees, which culminated in the comprehensive overhaul of the old Prison Law and its replacement by the Act on Penal Detention Facilities and Treatment of Inmates and Detainees in 2005.

- Important Precedent: While there were a few earlier instances where the Supreme Court had found delegated legislation unlawful (notably a 1963 criminal case regarding fishing regulations and the 1971 Agricultural Land Act Enforcement Order case concerning land resale ), this 1991 decision is particularly significant for its clear reasoning in the context of administrative regulations that impinge upon fundamental freedoms. It is part of a line of important Supreme Court cases that scrutinize the legality of administrative orders and regulations.

Conclusion

The 1991 Supreme Court ruling in the case of the refused prison visit serves as a powerful affirmation of the principle that administrative rulemaking, even when duly authorized by statute, must strictly adhere to the limits and purposes of that statutory authorization. This is especially critical when fundamental freedoms, such as a detainee's ability to maintain contact with the outside world, are at stake. The decision highlights the judiciary's role in maintaining the hierarchy of laws and ensuring that administrative convenience or long-standing practice does not override statutory mandates or constitutional principles. While the plaintiff in this specific case did not ultimately receive compensation due to the Court's finding on negligence, the judgment's invalidation of a decades-old regulation sent a clear message about the importance of respecting the scope of delegated legislative authority and contributed significantly to the reform of penal administration in Japan.