When Rehabilitation Fails: A 2014 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Secured Creditor Agreements in Subsequent Bankruptcy

In Japanese civil rehabilitation proceedings, a common and vital tool for facilitating a debtor company's turnaround is the "agreement on the right of separation" (別除権協定 - betsujoken kyōtei). This is a negotiated settlement between the financially distressed debtor company and its secured creditors regarding the treatment of secured claims and the underlying collateral. Typically, such an agreement might involve the debtor agreeing to pay a "redemption price" (受戻価格 - ukemodoshi kakaku) for the collateral—often its assessed value, which may be less than the full secured debt—in installments over time. In return, the secured creditor usually agrees not to foreclose on the collateral as long as the debtor adheres to the payment schedule, allowing the debtor to continue using essential assets for its business operations. These agreements often contain clauses specifying conditions under which they will terminate, such as the failure or non-confirmation of the overall rehabilitation plan.

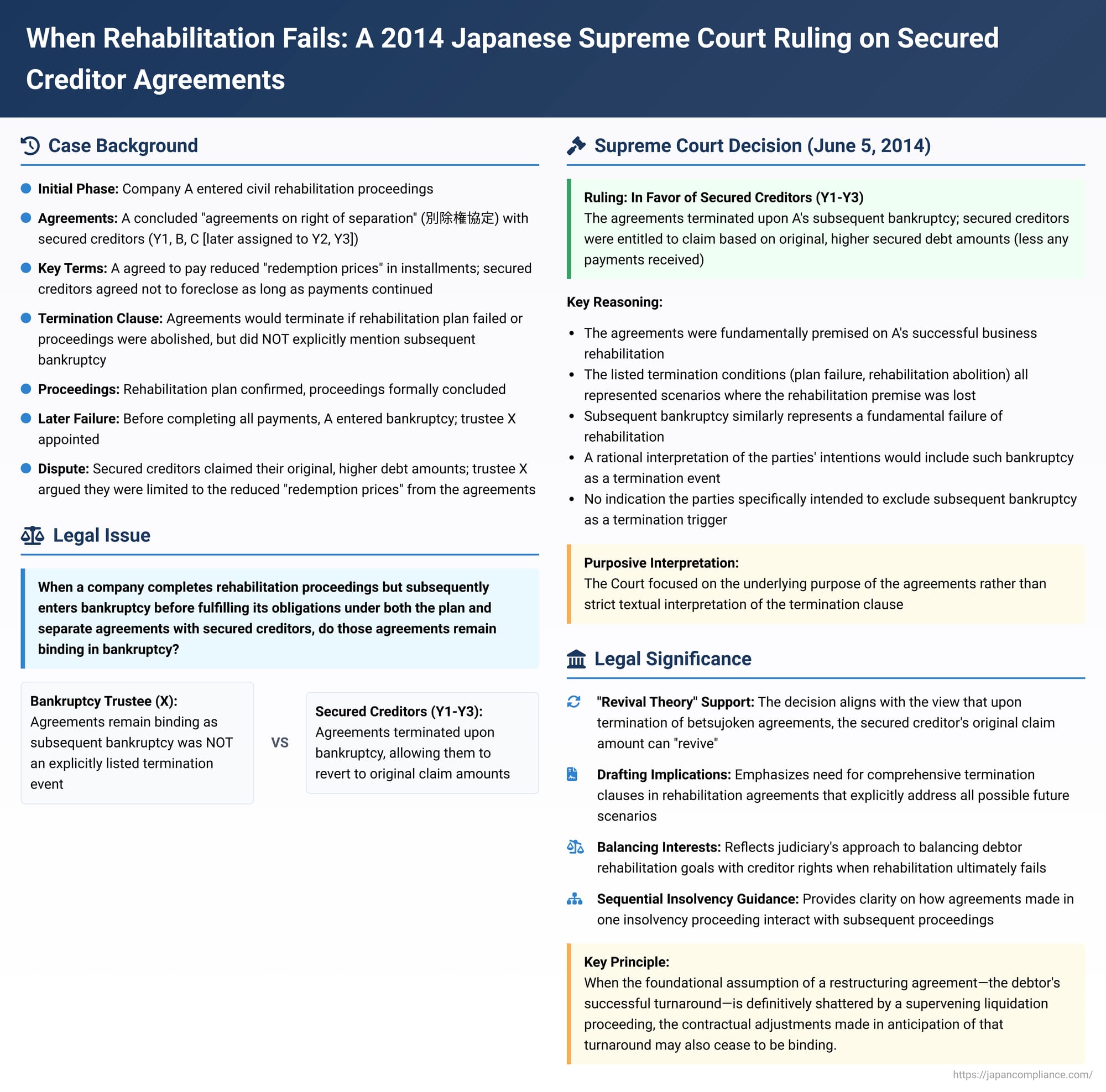

A complex legal question arises if a company, after its civil rehabilitation proceedings have formally concluded (meaning the plan is being implemented), subsequently fails to complete all its obligations under both the confirmed rehabilitation plan and such a betsujoken agreement, and then slides into bankruptcy. Does the betsujoken agreement—and specifically, the reduced claim amount based on the redemption price—remain binding in the new bankruptcy proceeding? Or does the agreement terminate, allowing the secured creditor to assert their original, larger claim? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this critical issue in a judgment on June 5, 2014.

Factual Background: Rehabilitation, Secured Creditor Agreements, and Subsequent Bankruptcy

The case involved A Co., a company that had entered civil rehabilitation proceedings. At the time these proceedings commenced, Y1, along with two other entities B and C (whose rights were later assigned to Y2 and Y3, respectively, who became the appellants), held mortgages (referred to as the "subject security interests") over A Co.'s real property, securing their respective claims against A Co.

During the civil rehabilitation process, A Co. (acting as the procedural entity, likely the debtor-in-possession or represented by a supervisor/trustee if a management order was in place) successfully negotiated and concluded betsujoken agreements with each of these secured creditors: Y1, B, and C. These agreements shared several key features:

- A Co. and the secured creditors formally acknowledged that, for the purpose of the agreement, the amount of the secured claims was effectively reduced to an agreed-upon "redemption price" for the respective encumbered properties. This redemption price was typically set at or near the current market value of the collateral and was often less than the full outstanding amount of the original secured debt.

- A Co. committed to paying this agreed redemption price to each secured creditor in installments over a period of several years.

- A Co. was permitted to continue using the mortgaged properties (which were essential for its business) as long as it complied with the installment payment schedule. If A Co. defaulted on two or more installments or other specified conditions occurred, the secured creditors would regain the right to enforce their security interests (e.g., foreclose on the properties).

- Upon A Co.'s full payment of the agreed redemption price, the respective security interests would be extinguished.

- The agreements also likely stipulated an "expected deficiency amount" (不足額確定合意 - fusokugaku kakutei gōi) for each secured creditor. This represented the portion of their original secured debt that exceeded the agreed redemption price, and for this deficiency, the creditors would typically participate as general rehabilitation creditors, receiving payments under the terms of A Co.'s overall rehabilitation plan.

- Crucially, each betsujoken agreement contained a termination clause (解除条件条項 - kaijo jōken jōkō). This clause specified certain events that would cause the agreement to terminate, such as: (a) the overall rehabilitation plan for A Co. failing to become legally effective, (b) the rehabilitation plan not being confirmed by the court, OR (c) the civil rehabilitation proceedings for A Co. being formally abolished (再生手続廃止の決定 - saisei tetsuzuki haishi no kettei) before the plan was completed. Notably, the termination clause did not explicitly list the subsequent commencement of bankruptcy proceedings against A Co. (especially after the rehabilitation proceedings themselves had formally concluded but before all plan and agreement payments were completed) as a trigger for termination.

A Co.'s rehabilitation plan, which incorporated these betsujoken agreements and provided for payments on the deficiency claims, was eventually confirmed by the court. Three years after the plan confirmation, A Co.'s civil rehabilitation proceedings were formally concluded by a court order (再生手続終結 - saisei tetsuzuki shūketsu), indicating that the plan was being duly implemented.

A Co. continued to make payments under both the confirmed rehabilitation plan and the betsujoken agreements for some time. However, before it could complete all these long-term payment obligations, A Co.'s financial situation deteriorated again, and it either filed for bankruptcy itself or had a bankruptcy petition filed against it by other creditors. Consequently, A Co. had new bankruptcy proceedings commenced against it, and X was appointed as its bankruptcy trustee.

Subsequently, the real properties that were the subject of the betsujoken agreements were sold through a foreclosure auction initiated by Y2 (as successor to B's rights). When the proceeds from this auction were to be distributed, a dispute arose. The proposed distribution table allocated funds to Y1, Y2, and Y3 based on their original, pre-agreement secured claim amounts (less any payments they had already received from A Co. under the plan or agreements). These original claim amounts were significantly higher than the "redemption prices" that had been stipulated in the earlier betsujoken agreements.

Bankruptcy trustee X objected to this proposed distribution. X argued that the secured creditors' claims should be capped at the (lower) redemption prices that had been agreed upon in the betsujoken agreements (again, less payments already received). X's position was that these agreements were still valid and binding, and therefore defined the maximum secured claim amount.

The Matsuyama District Court (first instance) rejected trustee X's objection, effectively siding with the secured creditors (Y1, Y2, Y3) and allowing them to claim based on their larger, original debt amounts. However, on appeal, the Takamatsu High Court reversed this decision, ruling in favor of trustee X. The High Court held that the betsujoken agreements had not terminated simply because A Co. had later entered bankruptcy. Since "subsequent bankruptcy after rehabilitation conclusion but before plan completion" was not an explicitly listed termination condition in the agreements, the High Court found the agreements (and their lower "redemption price" claim amounts) to be still in effect. The secured creditors Y1, Y2, and Y3 then appealed this High Court ruling to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Issue: Interpreting Termination Clauses in Betsujoken Agreements when Rehabilitation is Followed by Bankruptcy

The central legal question for the Supreme Court was one of contract interpretation: When a betsujoken agreement made during civil rehabilitation includes a termination clause listing specific rehabilitation-related failures (like non-confirmation of the plan or abolition of the proceedings) as triggers for termination, does that clause also implicitly cover the scenario where the debtor company successfully concludes its rehabilitation proceeding but then enters bankruptcy before fulfilling all its payment obligations under both the confirmed rehabilitation plan and the betsujoken agreement? If the agreement is deemed terminated by the subsequent bankruptcy, the secured creditor might be able to revert to claiming their original, larger debt. If the agreement remains in force, their secured claim would likely be limited to the agreed (and usually lower) "redemption price."

This required the Court to consider the parties' likely intent when they made these agreements and the fundamental purpose such agreements serve within the context of a civil rehabilitation aimed at business turnaround.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Subsequent Bankruptcy Does Terminate the Agreements, Reviving Original Claim Amounts

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of June 5, 2014, reversed the High Court's decision and reinstated the first instance judgment. This meant that the Court found that the betsujoken agreements had indeed terminated upon A Co.'s subsequent bankruptcy commencement. As a result, the secured creditors (Y1, Y2, and Y3) were entitled to have their claims in the bankruptcy distribution calculated based on their original, higher secured debt amounts (less, of course, any payments they had already received from A Co. under the plan or the agreements before the bankruptcy).

The Supreme Court's reasoning was based on a purposive and rational interpretation of the parties' intent behind the termination clauses in the betsujoken agreements:

- Underlying Premise of the Agreements: The Court started by emphasizing that the betsujoken agreements were clearly and fundamentally premised on the assumption that A Co.'s business would be successfully rehabilitated through the diligent execution of its civil rehabilitation plan. These agreements were specifically designed as tools to make that rehabilitation feasible, for instance, by allowing A Co. to retain use of essential assets while making reduced, structured payments.

- Listed Termination Conditions Reflect Loss of This Fundamental Premise: The termination conditions explicitly listed in the agreements—such as the rehabilitation plan failing to become legally effective, the plan not being confirmed by the court, or the entire civil rehabilitation proceeding being formally abolished—all represent scenarios where this underlying premise of successful rehabilitation through the plan is fundamentally lost.

- Subsequent Bankruptcy is Equivalent to Loss of This Premise: The Court then considered the scenario at hand: A Co.'s civil rehabilitation proceedings had formally concluded (meaning the plan was confirmed and had been in implementation for over three years), but A Co. subsequently entered bankruptcy before it could complete all its payment obligations under both the plan and the betsujoken agreements. The Supreme Court reasoned that this situation, where the company ultimately fails and enters bankruptcy before fulfilling the terms of its prior rehabilitation, is, in substance, no different from a situation where the rehabilitation proceedings are formally abolished (an event often triggered by the debtor's inability to implement the plan, which itself frequently leads to a direct transition to bankruptcy under court order). In both scenarios, the critical premise that A Co. would achieve successful business rehabilitation through the execution of its rehabilitation plan is irretrievably lost.

- Rational Interpretation of the Parties' Intent: The Court found no indication that the parties, when drafting the termination clauses, had specifically intended to exclude such a subsequent, pre-completion bankruptcy as a ground for termination, while explicitly including other forms of rehabilitation failure like plan non-confirmation or proceeding abolition. A rational interpretation of the contracting parties' intentions would be that the termination clause was meant to cover any situation where the fundamental goal of achieving rehabilitation through the agreed-upon plan became impossible.

- Consequence of Termination – Revival of Original Secured Claim Amounts: Since A Co. did, in fact, enter bankruptcy proceedings before fulfilling its obligations under the confirmed rehabilitation plan and the associated betsujoken agreements, the Supreme Court concluded that these agreements lost their legal effect from the moment of A Co.'s bankruptcy commencement. As a result, the amount of the secured claims held by Y1, Y2, and Y3 reverted from the contractually reduced "redemption prices" back to their original, larger amounts (less any payments A Co. had already made). The distribution table prepared in the bankruptcy auction, which was based on these higher, revived claim amounts, was therefore deemed correct.

The "Revival Theory" vs. "Fixation Theory" in Context

The PDF commentary accompanying this case delves into a broader academic debate in Japanese insolvency law concerning the effect of terminating a betsujoken agreement, especially one that includes a "deficiency confirmation agreement" (不足額確定合意 - fusokugaku kakutei gōi) where the secured creditor agrees to reduce their secured claim to the value of the collateral (the redemption price) and treat the rest as an unsecured claim. The debate centers on what happens if the betsujoken agreement is later terminated:

- The "Revival Theory" (復活説 - fukkatsu setsu): This theory argues that upon the termination of the betsujoken agreement, the secured creditor's original, larger secured claim amount "revives" (after crediting any payments already received under the agreement or plan). The Supreme Court's decision in this 2014 case, by allowing the secured creditors to claim based on their original, larger debt amounts after the betsujoken agreements were deemed terminated by the subsequent bankruptcy, is seen by many commentators as being consistent with, or supportive of, this "revival theory," at least in circumstances where the termination is due to a fundamental frustration of the rehabilitation's purpose.

- The "Fixation Theory" (固定説 - kotei setsu): This opposing theory argues that once a secured claim is contractually reduced to an agreed-upon redemption price within a betsujoken agreement, that reduction is generally final and the claim does not automatically revert to its original, higher amount even if the betsujoken agreement itself is later terminated for some reason (unless the agreement itself explicitly provides for such revival).

The PDF commentary suggests that the Supreme Court's 2014 decision does not definitively settle the broader revival versus fixation debate for all possible scenarios of betsujoken agreement termination (for example, if termination occurs due to the debtor's simple default on installment payments without a new supervening insolvency proceeding). The specific facts of this case, involving a subsequent bankruptcy that fundamentally undermined the entire basis of the prior rehabilitation effort, were key to the Court's purposive interpretation of the termination clause.

Implications for Secured Creditors and Restructuring Agreements

This Supreme Court judgment carries important implications:

- Importance of Comprehensive Termination Clauses: It underscores the need for extremely careful and comprehensive drafting of termination clauses in betsujoken agreements made during civil rehabilitation or corporate reorganization. Parties should endeavor to explicitly address various potential future scenarios, including the possibility of a subsequent bankruptcy proceeding before full plan/agreement performance, if they wish to achieve a different outcome regarding claim amounts.

- Balancing Debtor Rehabilitation Goals with Creditor Rights: The decision reflects the judiciary's attempt to strike a balance. Betsujoken agreements are crucial tools for facilitating debtor rehabilitation by allowing continued use of essential assets. However, if the rehabilitation ultimately fails and is superseded by a liquidation proceeding (bankruptcy), the concessions made by secured creditors in those agreements (like reducing their secured claim to the collateral's value) may no longer be binding if the fundamental premise of those concessions—successful rehabilitation—has collapsed.

- Complexities of Sequential Insolvency Proceedings: The case illustrates the significant legal complexities that can arise when a company goes through one form of insolvency proceeding (like civil rehabilitation, which aims for restructuring) and then, due to continued financial failure, subsequently enters another, often more terminal, form of proceeding (like bankruptcy, which usually aims for liquidation). The interaction of agreements made in the first proceeding with the rules of the second proceeding requires careful legal analysis.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's June 5, 2014, decision provides important guidance on the interpretation of termination clauses within "agreements on the right of separation" (betsujoken kyōtei) when a company's civil rehabilitation effort is ultimately followed by bankruptcy before the rehabilitation plan is fully executed. By adopting a purposive interpretation focused on the underlying premise of successful rehabilitation, the Court held that a subsequent bankruptcy, even if not explicitly listed as a termination trigger, can cause such agreements to lose their effect. This, in turn, can allow secured creditors to assert their original, larger claim amounts (less any payments already received) in the ensuing bankruptcy distribution. This ruling emphasizes that when the foundational assumption of a restructuring agreement—the debtor's successful turnaround—is definitively shattered by a supervening liquidation proceeding, the contractual adjustments made in anticipation of that turnaround may also cease to be binding.