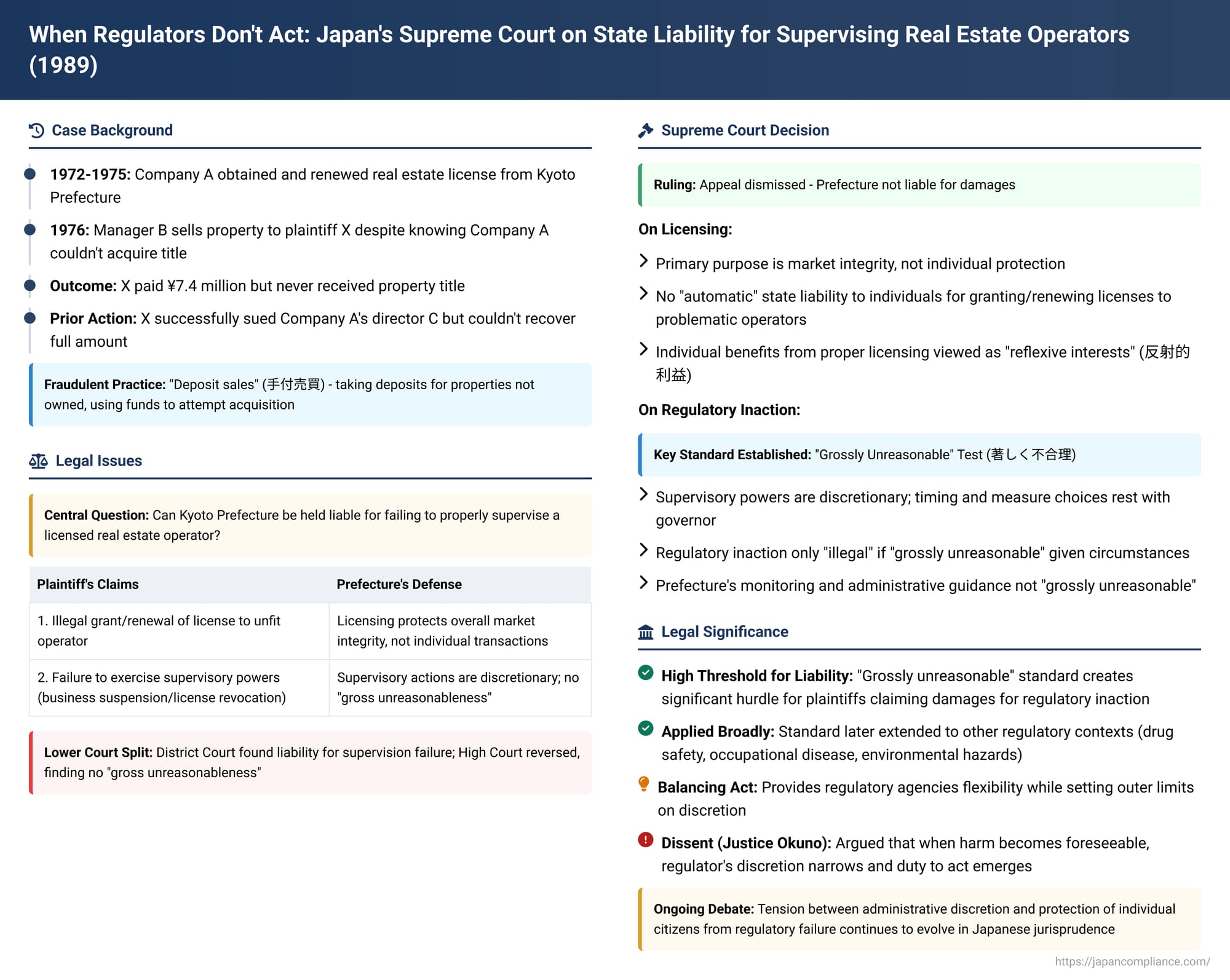

When Regulators Don't Act: Japan's Supreme Court on State Liability for Supervising Real Estate Operators

Date of Judgment: November 24, 1989

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

On November 24, 1989, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment in a case concerning the scope of state compensation liability for damages suffered by a citizen due to the fraudulent activities of a licensed real estate operator. The lawsuit specifically questioned whether a prefectural government could be held liable for allegedly acting illegally in (1) granting and renewing the realtor's license, and (2) subsequently failing to exercise its supervisory powers (such as business suspension or license revocation) against the problematic operator. This decision is a leading authority in Japanese administrative law, particularly for establishing a high threshold—that of "gross unreasonableness"—for finding state liability arising from the non-exercise of regulatory or supervisory powers. It also delved into the extent to which licensing systems are intended to protect the interests of individual transaction parties for the purposes of state compensation.

I. A Real Estate Deal Gone Wrong: The Factual Background

The case arose from a series of deceptive real estate transactions conducted by a licensed operator in Kyoto Prefecture.

The Licensed Operator and its Management:

A limited company, referred to here as Company A, had been granted a license to conduct real estate transaction business by the Governor of Kyoto Prefecture in October 1972. This license was subsequently renewed in October 1975. The de facto manager of Company A was an individual named B, while the registered representative director was C.

The Fraudulent Scheme – "Deposit Sales":

B, as the effective manager of Company A, engaged in a highly risky and often fraudulent business practice known as "deposit sales" (tetsuke baibai). This method involved Company A (under B's direction) taking substantial deposits, and often interim payments, from prospective property buyers for properties that Company A did not actually own at the time of the sale agreement. The general modus operandi was for B to use these customer funds to then attempt to acquire the target property from its true owner, with the intention of selling it on to the customer, hopefully at a profit. This practice inherently carried a high risk of failure if Company A could not subsequently secure title to the property.

The Plaintiff's Ill-Fated Transaction:

In September 1976, B, acting through Company A, entered into a contract to sell a property to X, the plaintiff in this case. Crucially, at the time of this sale agreement, B was aware that Company A had no realistic prospect of actually acquiring the title to this specific property and therefore would be unable to transfer it to X as promised. X, presumably unaware of this critical impediment, proceeded to pay a deposit and a subsequent interim payment to Company A. These funds, however, were allegedly diverted by B for other purposes, and Company A never acquired or transferred the property to X.

The Outcome for X – Financial Loss:

As a direct result of Company A's failure to deliver title to the property as contracted, X was unable to acquire the property for which substantial payments had been made. X consequently suffered a significant financial loss, quantified at JPY 7.4 million.

Prior Legal Action Against Company A's Representative:

Before initiating the lawsuit against Kyoto Prefecture, X had successfully sued C, the registered representative director of Company A, for damages arising from the failed transaction. The first instance court had ruled in X's favor in that lawsuit, and this judgment against C had become final and conclusive. It is implied that full recovery from C or Company A was likely not achieved, prompting the subsequent claim against the prefecture.

The Lawsuit Against Kyoto Prefecture (Y):

X then filed a lawsuit against Y (Kyoto Prefecture) seeking state compensation under Article 1, paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act. X's claims against the prefecture were based on two main allegations of illegal conduct by the Governor (acting through prefectural officials):

- That the Governor of Kyoto Prefecture had acted illegally in initially granting Company A its real estate business license and in later renewing that license. The implication was that Company A, or its principals like B, were fundamentally unfit to hold such a license due to their business practices or lack of integrity, and that the license should not have been issued or renewed had proper diligence been exercised by the licensing authority.

- That the Governor had also acted illegally by failing to exercise appropriate supervisory powers as mandated under the Real Estate Transaction Business Law (REBL). X argued that given Company A's problematic and allegedly fraudulent conduct (which presumably had generated complaints or should have been discoverable), the Governor should have taken timely and decisive disciplinary actions against Company A. Such actions could have included ordering a suspension of its business operations or, ultimately, revoking its license. X contended that this failure of regulatory oversight (a form of regulatory inaction) was a cause of the damages X subsequently suffered.

II. The Lower Courts' Diverging Views on State Liability

The case progressed through the Japanese court system with differing outcomes at the District Court and High Court levels regarding the state compensation claim.

Kyoto District Court (First Instance):

The Kyoto District Court, in adjudicating X's state compensation claim against Kyoto Prefecture, made the following findings:

- Regarding the initial granting and subsequent renewal of Company A's real estate license, the District Court found that these licensing decisions by the Governor were indeed illegal (presumably because it determined that Company A or its principals did not meet the statutory fitness requirements for holding such a license). However, despite this finding of illegality in the licensing process itself, the District Court denied X's claim for damages on this particular ground. It concluded that there was no legally sufficient causal link between the flawed licensing decisions and the specific financial damages that X had suffered in the later transaction.

- Regarding X's second claim—which concerned the Governor's alleged failure to exercise supervisory powers against Company A—the District Court found that this regulatory inaction was illegal. Furthermore, it found that there was a causal link between this illegal failure to supervise and the damages sustained by X. Consequently, the District Court partially upheld X's claim on this basis and ordered Kyoto Prefecture to pay a portion of the damages claimed by X.

Osaka High Court (Appeal):

Kyoto Prefecture appealed the District Court's decision to the Osaka High Court. The Osaka High Court reversed the part of the District Court judgment that had found in favor of X and had ordered the prefecture to pay damages. The High Court specifically addressed the issue of the Governor's failure to exercise supervisory powers over Company A. It concluded that this inaction, when assessed under the circumstances, was not "grossly unreasonable" (ichijirushiku fugōri) and therefore did not reach the level of illegality required to trigger state compensation liability under Japanese law.

Following this adverse decision from the Osaka High Court, X, the plaintiff, appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan.

III. The Supreme Court's Judgment: Setting a High Bar for State Liability Due to Regulatory Inaction

The Supreme Court of Japan, in its judgment dated November 24, 1989, ultimately dismissed X's appeal. In doing so, it affirmed the Osaka High Court's decision that Kyoto Prefecture was not liable for damages. The Supreme Court's reasoning provided important clarifications on the standards for state liability in cases involving allegedly flawed licensing and failures of regulatory oversight.

A. Regarding the Alleged Illegality of Granting or Renewing the Real Estate License

- Primary Purpose of the Real Estate Business Licensing System: The Supreme Court began its analysis by defining what it considered to be the primary purpose of the licensing system established under Japan's Real Estate Transaction Business Law (REBL). It stated that the "direct purpose of the licensing system... is to ensure the fairness of transactions and to promote the smooth distribution of land and buildings by preemptively excluding real estate businesses that pose a risk to the safety of real estate transactions". This frames the system as being primarily aimed at maintaining overall market integrity and efficiency.

- Protection of Individual Transaction Parties as an Indirect or Ultimate Goal, Not a Direct Guarantee: The Court acknowledged that the REBL does contain various provisions that take into account the protection of the interests of individual parties involved in real estate transactions. For example, Article 1 of the REBL explicitly lists the protection of purchasers and other related parties as one of its objectives, and the law mandates measures like business security deposits to provide a source of compensation for wronged clients. The Supreme Court conceded that the licensing system, in an ultimate or indirect sense, does contribute to the protection of these individual interests.

- Licensing System Does Not Generally Guarantee an Operator's Character or Directly Aim to Prevent Specific Individual Damages: However, the Supreme Court drew a critical distinction regarding the direct aims of the licensing system in the context of state compensation. It held that the system's purpose does not extend to providing a general, state-backed guarantee of the personal integrity, financial soundness, or ethical character of every individual or company that receives a real estate operator's license. Furthermore, the Court stated that it is "difficult to readily construe" that the licensing system's direct objective is the prevention of, or the provision of a specific remedy for, concrete financial damages that might be suffered by individual transaction parties due to the fraudulent or otherwise improper acts of a duly licensed operator. The redress for such specific, individualized damages, the Supreme Court implied, is generally to be sought through ordinary private law remedies, such as tort claims or breach of contract actions brought directly against the wrongdoing operator or its principals.

- Conclusion on Licensing Illegality for State Compensation Purposes: Based on this understanding of the licensing system's primary purpose, the Supreme Court concluded that the act of a governor (or other licensing authority) granting or renewing a real estate business license—even if it is subsequently determined that the operator did not, in fact, fully meet all the statutory licensing criteria at the time (e.g., due to undisclosed prior misconduct or financial instability)—does not immediately or automatically constitute an "illegal act" in relation to individual parties who subsequently transact with that operator, for the purposes of invoking state compensation liability under Article 1, paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act.

- The PDF commentary accompanying this case suggests that this part of the Supreme Court's ruling effectively treats the benefit that individual transaction parties derive from the proper administration of the licensing system as a "reflexive interest" (hansha-teki rieki). A reflexive interest is generally understood as an indirect benefit that an individual might receive as a consequence of a law that is primarily aimed at achieving a broader public good or maintaining public order, rather than directly conferring an enforceable right upon that individual against the state for flawed administration. While the Supreme Court did not explicitly use the term "reflexive interest" in its judgment, its reasoning here aligns closely with that concept. The commentary also notes that this view has been subject to academic criticism, with some scholars arguing that various specific provisions within the REBL (such as those mentioned above concerning purchaser protection and security deposits) do indeed indicate a more direct legislative intent to protect individual transaction parties, which should be given greater weight when assessing state liability for failures in the licensing or supervision process. The Supreme Court's careful phrasing—that flawed licensing is not "immediately... illegal"—also leaves a slight theoretical opening, suggesting that the Court did not entirely rule out the possibility that, in some exceptional circumstances, a flawed licensing decision could be deemed illegal for state compensation purposes in relation to an individual. However, the judgment did not provide any specific criteria for when such a situation might arise.

B. Regarding the Alleged Illegality of Failing to Exercise Supervisory Powers (Regulatory Inaction)

- The Discretionary Nature of Supervisory Powers: The Supreme Court then turned to X's second major claim: that the Governor of Kyoto Prefecture had acted illegally by failing to exercise appropriate supervisory powers against Company A, such as ordering a suspension of its business operations or revoking its license, particularly once evidence of its problematic and potentially fraudulent conduct began to emerge. The Court began by emphasizing that the Real Estate Transaction Business Law grants governors (and other relevant authorities) a range of supervisory powers over licensed real estate operators. These powers include the authority to issue necessary instructions for business improvement, to order the suspension of business operations for a specified period, or, in more serious cases, to revoke an operator's license entirely. The Court stressed that the decision of which of these various supervisory measures to take, if any, and, critically, when to exercise such powers, is generally entrusted to the "reasonable discretion of the governor based on professional judgment". This acknowledges that regulators often need flexibility to tailor their responses to the specific circumstances of each case.

- The "Grossly Unreasonable" (ichijirushiku fugōri) Standard for Finding Illegality in Regulatory Inaction: Based on this understanding of the discretionary nature of most supervisory powers, the Supreme Court established a notably high threshold for finding that a failure to exercise such powers (i.e., regulatory inaction) constitutes an "illegal" act for the purposes of state compensation liability. It ruled: "Therefore, even if an individual transaction party suffers damage due to the improper conduct of such a business operator, unless the non-exercise of [supervisory] authority, under the specific circumstances and in light of the purpose and objectives for which such supervisory authority was granted to the governor, is found to be grossly unreasonable (ichijirushiku fugōri), the said non-exercise of authority should not be evaluated as illegal for the application of Article 1, paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act in relation to the said transaction party". This "grossly unreasonable" standard implies that mere error in judgment, or a failure to take what might, with hindsight, appear to be the optimal regulatory action, is not sufficient to trigger state liability. The inaction must be so lacking in rationality, given the circumstances and the aims of the regulatory scheme, as to be indefensible.

- Application of the "Grossly Unreasonable" Standard to the Facts of This Case: Although the provided PDF snippet does not detail the Supreme Court's full application of this standard to the specific facts involving Company A, the commentary indicates that the Court, in its complete reasoning, considered the actions that were taken by the Kyoto prefectural officials. This included monitoring complaints against Company A and engaging in "administrative guidance" (gyōsei shidō) with both Company A and some of the affected victims in an attempt to resolve issues. The Supreme Court ultimately concluded that the failure of these officials to escalate their intervention to formal disciplinary actions, such as license revocation or a mandatory business suspension, before X's damaging transaction occurred, was not "grossly unreasonable" in the specific circumstances as presented to the Court. Therefore, the claim based on regulatory inaction also failed.

- The Dissenting Opinion of Justice Okuno: It is important to acknowledge that this aspect of the Supreme Court's decision was not unanimous. Justice Okuno issued a dissenting opinion. He argued that while the exercise of supervisory powers is generally discretionary, this discretion is not absolute and must be exercised in a way that serves the protective purposes of the Real Estate Transaction Business Law. Justice Okuno contended that when it becomes foreseeable to the regulatory authority that failing to take decisive supervisory action (such as license revocation or business suspension) against a demonstrably delinquent real estate operator will inevitably lead to an increase in, or a continuation of, harm to transaction parties—thereby frustrating the fundamental purpose of the REBL, which includes protecting those parties—then the governor (or other supervising authority) no longer has the discretion to simply refrain from acting. At such a critical point, Justice Okuno argued, a positive duty arises for the governor to take appropriate and reasonably timely supervisory action to prevent further harm. He also suggested that this duty is owed even in relation to future transaction parties who might be victimized if the delinquent operator is allowed to continue its improper activities unchecked.

IV. Legal Commentary and Analysis: Understanding the Scope of State Duty in Regulatory Contexts

This 1989 Supreme Court judgment has been a focal point of extensive legal commentary in Japan, particularly for its pronouncements on state liability for regulatory inaction and the scope of protection afforded by licensing regimes.

A Leading Case Establishing the "Grossly Unreasonable" Standard for Regulatory Inaction:

- This decision is widely recognized by legal scholars in Japan as a leading, if not foundational, case concerning state compensation liability for the failure of regulatory authorities to properly exercise their supervisory powers over private entities—a scenario often termed "regulatory inaction" (kisei kengen no fukōshi). The demanding "grossly unreasonable" (ichijirushiku fugōri) standard articulated by the Supreme Court in this decision for determining the illegality of such inaction has proven to be highly influential in subsequent jurisprudence. The PDF commentary explicitly states that this precise standard was later generalized by the Supreme Court and applied as a benchmark in other significant state compensation cases involving different regulatory contexts, including those concerning drug safety (notably, the Chloroquine drug injury litigation), occupational diseases (such as the Chikuhō dust lung disease litigation and the Minamata disease Kansai litigation), and public health issues related to asbestos exposure (the Sennan asbestos litigation). This consistent application across diverse fields underscores the foundational nature of the legal principle established in this 1989 real estate supervision case.

The Scope of Protection Afforded by Licensing Systems and the "Reflexive Interest" Debate:

- The Supreme Court's reasoning concerning the alleged illegality of the initial granting and subsequent renewal of Company A's real estate license (summarized as Point I in the judgment analysis above) touches upon a complex and frequently debated area of administrative law: the extent to which regulatory licensing schemes are deemed to protect the private, individual interests of persons who transact with the entities that are licensed under those schemes, as opposed to primarily serving broader public interests such as market order or general safety. The Court's conclusion that the real estate licensing system does not directly aim to prevent or specifically remedy individual financial damages suffered by particular transaction parties, and its suggestion that redress for such damages is generally to be sought through private law remedies against the wrongdoing operator, effectively treats the benefit that an individual transaction party derives from the proper administration of the licensing system as an indirect or "reflexive interest" (hansha-teki rieki). While the Supreme Court did not explicitly use the term "reflexive interest" in its judgment, its underlying reasoning aligns closely with this traditional legal concept. A reflexive interest is generally understood in Japanese administrative law as an incidental benefit that an individual might happen to receive as a consequence of a law that is primarily aimed at achieving a broader public good or maintaining public order, rather than being intended to directly confer an individually enforceable legal right upon that person against the state for flawed administration of that law.

- This particular perspective adopted by the Court, as the PDF commentary notes, has been subject to considerable academic criticism. Critics often point to various specific provisions within regulatory statutes like the Real Estate Transaction Business Law (REBL)—such as Article 1 of the REBL, which explicitly includes the protection of purchasers and other related parties among its stated objectives; Article 65, paragraph 1, item (i), which empowers the governor to issue necessary instructions to a realtor if their actions are deemed likely to harm the interests of transaction parties; and the mandatory 営業保証金 (eigyō hoshōkin) or business security deposit system, which is specifically designed to provide a fund for compensating clients who have been wronged by a realtor—as clear evidence that these laws do indeed have a direct and intentional protective purpose for individual transaction parties. These critics argue that this direct protective purpose should be given more significant weight by the courts when they are assessing the state's potential liability for serious failures in the licensing or ongoing supervision process.

- The PDF commentary also astutely points out that the Supreme Court's careful and somewhat guarded phrasing in its judgment—stating that flawed licensing is not "immediately" or "automatically" illegal in relation to individual transaction parties—does leave a slight theoretical opening. It suggests that the Court did not entirely and definitively rule out the possibility that, in some exceptional or particularly egregious circumstances, a flawed licensing decision could be deemed illegal for state compensation purposes in relation to an individual. However, the 1989 judgment unfortunately did not provide any specific criteria or guidance for determining when such a situation might arise, leaving this as an area for potential future jurisprudential development.

Regulatory Inaction as a Matter of Discretion and the Application of the "Grossly Unreasonable" Standard:

- The Supreme Court's treatment of the prefectural governor's failure to exercise supervisory powers against Company A (summarized as Point II in the judgment analysis) by framing it primarily as an issue of administrative discretion, subject to judicial review only for "gross unreasonableness," is a common and characteristic approach in Japanese administrative law when courts are called upon to assess liability for alleged regulatory inaction. The core legal question in such cases, as the PDF commentary suggests, is not so much about affixing a precise doctrinal label like "abuse of discretion" or "non-exercise of a discretion that has shrunk to zero," but rather about how courts substantively evaluate the entirety of the factual circumstances and the regulator's conduct (or lack thereof) to determine if the inaction complained of crosses the high threshold of "gross unreasonableness" and thus becomes legally actionable.

- The commentary posits that although the Supreme Court did not explicitly enumerate them in this judgment, its holistic assessment of "gross unreasonableness" likely involves, in substance, a comprehensive consideration of several factors that are also common to general tort liability analysis. These would typically include the importance and nature of the legal interest that was ultimately harmed by the inaction, the degree of foreseeability of that harm occurring if no regulatory action was taken, the actual possibility of avoiding or mitigating the harm through timely and appropriate regulatory intervention, and the overall reasonableness of expecting the regulatory authority to have acted under the specific circumstances (this latter element is often referred to in Japanese legal theory as "expectancy" or kitai kanōsei – the possibility of expecting a certain action).

- The PDF commentary also makes an interesting observation regarding the full reasoning of the Supreme Court (a portion of which was not detailed in the provided PDF snippet). It notes that the Supreme Court, in reaching its conclusion that the inaction was not grossly unreasonable, appears to have given positive weight to the fact that "after the renewal of the license in question, the responsible [prefectural] officials monitored the progress of negotiations between Company A and the [previously identified] victims, explored possibilities for victim relief, and continued to provide administrative guidance [gyōsei shidō]". This suggests that evidence of ongoing, albeit perhaps ultimately insufficient or ineffective, administrative efforts to address a problem might weigh against a judicial finding that the regulator's inaction was "grossly unreasonable."

- However, the commentary also raises a critical counter-perspective from the facts of this case. Given the prior history of B, the de facto manager of Company A (which reportedly included a previous conviction for violations of the REBL, and the fact that Company A's license had been renewed while B was still under a suspended sentence for that prior offense), a compelling argument could be made that the administrative authorities had, in a sense, contributed to creating a dangerous situation by allowing such an operator with a problematic history to continue in business. From this viewpoint, merely providing administrative guidance to an entity with such a track record might be seen as an inadequate or insufficiently robust response, and the failure to take more decisive and formal disciplinary action much sooner could indeed be viewed as more problematic and potentially "grossly unreasonable".

The Interplay Between the Court's View on Licensing and Its View on Subsequent Supervisory Duties:

- The PDF commentary makes an insightful point about the potential interplay between the Supreme Court's findings on the initial licensing issue (Point I of the judgment summary) and its subsequent findings on the failure to exercise supervisory powers (Point II). It notes that the Supreme Court, in its discussion of Point II (regulatory inaction), did not explicitly reiterate or extensively discuss the "scope of protection" afforded to third parties in the context of supervisory inaction, as it had done when discussing the initial licensing decisions in Point I. The commentary suggests that the Supreme Court's adoption of a "reflexive interest"-like approach in Point I (which effectively downplayed the direct protection afforded to individual transaction parties by the mere act of licensing) might have been "one reason" why, when it later came to consider the failure of the governor to exercise supervisory powers against Company A, it did not place heavy emphasis on the initial (alleged) illegality of the license grant or renewal as a factor that might have exacerbated the wrongfulness of the later failure to supervise effectively. In other words, if the initial licensing decision itself was not seen as creating a strong, direct legal duty owed by the state to protect individual X from Company A's future misconduct, then a subsequent failure to adequately supervise that same company might be judged by a somewhat different or perhaps less stringent standard regarding its impact on X.

Subsequent Developments in Lower Court Case Law:

- It is also interesting to note, as the PDF commentary does, that some subsequent lower court decisions in Japan, while formally citing this 1989 Supreme Court judgment and its "grossly unreasonable" standard for regulatory inaction, have nonetheless found state liability for failures to properly supervise other types of businesses (for example, in cases involving fraudulent activities by mortgage securities companies or serious mismanagement within certain types of cooperative societies). In those later cases, the lower courts either appeared to apply the "grossly unreasonable" standard with a greater degree of effective scrutiny given the specific egregious facts before them, or they found that the nature of the interest held by the plaintiffs in those particular regulatory contexts was more than merely "reflexive" and thus deserved stronger and more direct protection from regulatory failure. This suggests that while the Supreme Court in 1989 certainly set a high bar for liability, its application by lower courts can still be highly fact-intensive and may, in appropriate circumstances, lead to findings of state liability for regulatory inaction.

V. Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's November 24, 1989, judgment in this case concerning the supervision of a real estate operator is a seminal decision in the complex field of state compensation law. It established two key principles that continue to influence Japanese administrative law. Firstly, the Court held that while the primary purpose of a regulatory licensing system, such as that for real estate businesses, is to ensure overall market fairness and stability, this does not automatically translate into direct state liability to individual consumers for financial damages they may suffer due to the misconduct of a licensed operator, even if the license itself was arguably improperly granted or renewed. The protection afforded to individuals in this regard is often seen as indirect.

Secondly, and perhaps more significantly for the broader landscape of regulatory accountability, the Court articulated the highly influential "grossly unreasonable" standard for assessing the illegality of a regulator's failure to exercise their discretionary supervisory powers. This standard sets a notably high threshold for plaintiffs seeking damages for regulatory inaction, requiring them to demonstrate that the authority's failure to intervene was not merely an error in judgment or a suboptimal policy choice, but so lacking in rationality, given all the circumstances, as to be legally indefensible. While this standard provides a degree of protection to regulatory agencies in their challenging task of discretionary decision-making, this landmark ruling, particularly through its strong dissenting opinion and its interpretation in subsequent lower court cases, continues to fuel an important and ongoing debate in Japan about the precise scope of the state's duty to protect its citizens from harm caused by inadequately supervised or regulated entities.