When Reality Blurs: Japan's Supreme Court on Acts by Schizophrenic Individuals and the Medical Treatment & Supervision Act

Date of Decision: June 18, 2008, Supreme Court of Japan (Third Petty Bench)

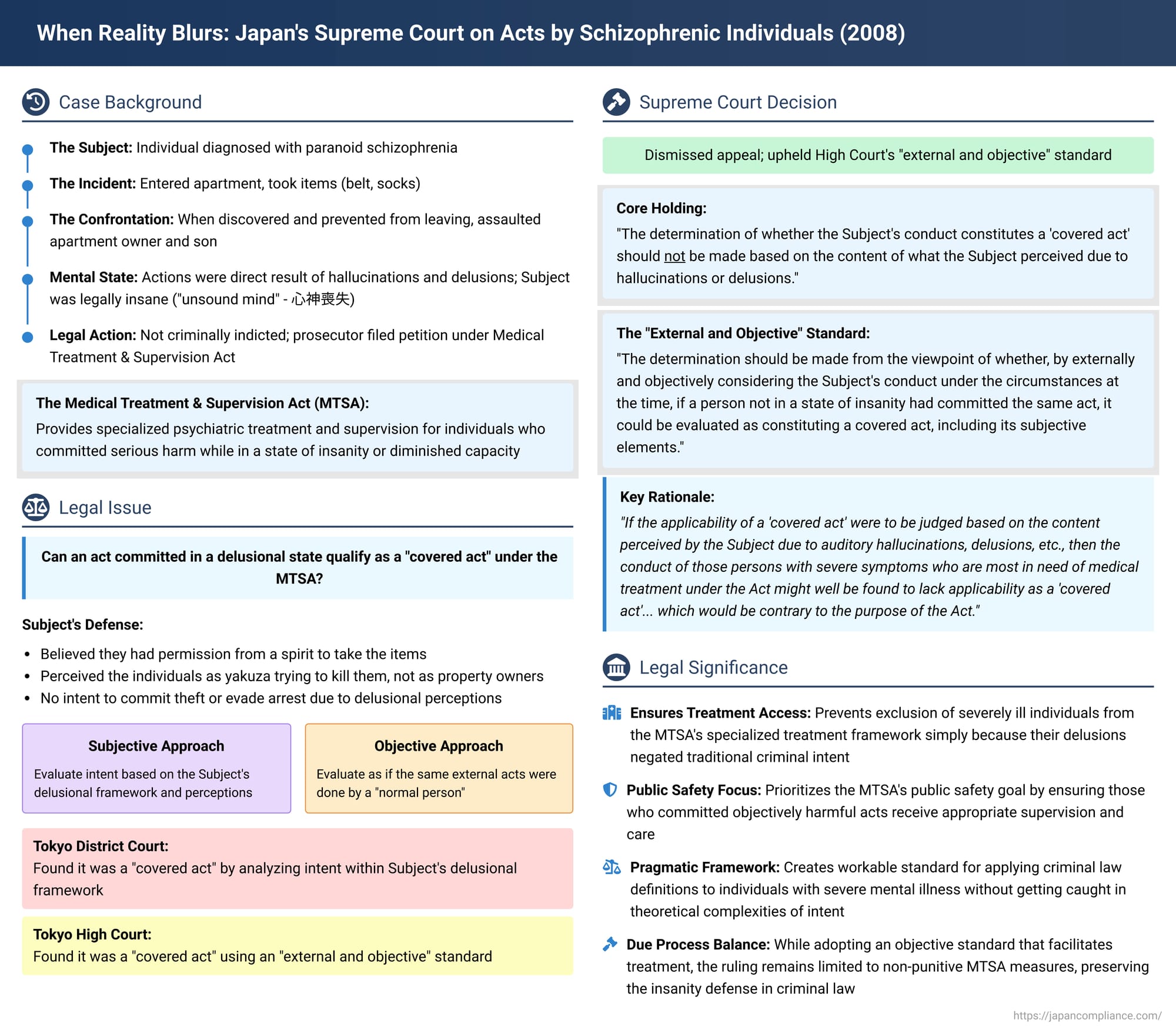

Japan's legal system, like many others, faces the complex challenge of addressing harmful acts committed by individuals suffering from severe mental illness. When such individuals are found to be legally insane or to have diminished capacity at the time of their actions, they may not be held criminally responsible in the traditional sense. Instead, Japan's "Act for Medical Treatment and Supervision of Persons Who Have Caused Serious Harm to Others in a State of Insanity or Diminished Capacity" (commonly known as the 医療観察法 - Iryō Kansatsu Hō, or the Medical Treatment and Supervision Act, MTSA) provides a specialized system for their compulsory psychiatric treatment and supervision. A key Supreme Court decision on June 18, 2008, clarified how courts should determine whether an act committed by an individual in a delusional state, specifically due to paranoid schizophrenia, qualifies as a "covered act" (対象行為 - taishō kōi) triggering the application of this Act.

The Incident: A Delusional State and Harmful Actions

The case involved an individual (referred to as "the Subject") diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. The incident unfolded as follows:

- The Subject unlawfully entered the apartment of Mr. B through an unlocked door.

- Inside, the Subject took a belt belonging to Mr. B's son, C, and a pair of socks belonging to Mr. B.

- The Subject was discovered by Mr. B's wife, D, who immediately contacted her husband.

- Mr. B and his son C rushed to the apartment. Mr. B then called the police to report a burglary.

- To prevent the Subject from escaping, C grabbed hold of the belt the Subject was wearing (or had slung over their shoulder).

- At this point, the Subject suddenly became violent, assaulting both C and Mr. B, and causing them physical injuries.

It was established that the Subject's actions—from entering the apartment to the assault—were a direct result of auditory hallucinations, delusions, and other symptoms stemming from their paranoid schizophrenia. The Subject was found to have been in a state of "unsound mind" (心神喪失 - shinshin sōshitsu, equivalent to legal insanity) at the time of these events.

Consequently, the public prosecutor decided not to indict the Subject for criminal offenses (such as theft and assault or robbery). Instead, recognizing the severity of the acts and the Subject's mental state, the prosecutor filed a petition with the court to place the Subject under the MTSA, asserting the need for specialized medical treatment and supervision.

The Legal Challenge: Defining a "Covered Act" under the MTSA

For the MTSA to apply, the individual must have committed a "covered act," which is defined in Article 2 of the Act as one of several specified serious offenses (e.g., homicide, robbery, arson, sexual offenses, injury). In this case, the act in question was potentially "robbery by ex post facto force" (事後強盗 - jigo gōtō), which in Japanese law involves committing a theft and then, to prevent arrest, recover the goods, or destroy evidence, resorting to violence or threats. This crime, like most listed in the MTSA, requires specific criminal intent (subjective elements, or mens rea).

The court-appointed attendant (付添人 - tsukisoinin, legal counsel for the Subject in MTSA proceedings) argued that the Subject's actions did not meet the criteria for a "covered act" because their delusional state negated the necessary criminal intent:

- No Intent for Theft: The Subject believed they had received explicit permission from the deceased former owner of the belt and socks (who communicated with them from the spirit world) to take these items.

- No Intent to Evade Arrest: The Subject perceived Mr. B and C not as individuals attempting to apprehend a thief, but as yakuza (organized crime members) who were trying to kill them. Thus, the Subject did not believe their actions were aimed at effecting an arrest.

- Mistaken Self-Defense (誤想防衛 - gosō bōei): The Subject misidentified Mr. B and C's actions as an imminent and unlawful attack, and therefore, the assault was committed in the delusional belief that it was necessary to protect themselves.

Based on these arguments, the attendant contended that the essential subjective elements of robbery by ex post facto force were absent, meaning no "covered act" had occurred, and thus, the MTSA should not apply.

Lower Court Rulings:

- Tokyo District Court: The District Court found that the Subject's actions did constitute a "covered act." It attempted to find the requisite intent (for theft and evading arrest) by analyzing the Subject's actions from within their delusional framework. It rejected the claim of mistaken self-defense.

- Tokyo High Court: The High Court also concluded that a "covered act" had occurred but adopted a different line of reasoning. It held that the determination should not be based on the Subject's internal, delusional perceptions. Instead, the Subject's conduct should be viewed "objectively and externally" (kyakkanteki-teki, gaikei-teki ni). The critical question, according to the High Court, was whether, if a "normal person" (tsūjō-jin) had committed the same external acts, the subjective elements of the crime (like intent) would be found. The High Court concluded that if an ordinary person had acted in the same way, they would be deemed to have stolen the items and then used violence to evade arrest. It also dismissed the mistaken self-defense argument on this objective basis.

The attendant appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court, arguing, inter alia, that subjecting an individual to confinement under the MTSA for an act that lacked genuine subjective criminal elements would violate the due process protections of Article 31 of the Japanese Constitution.

The Supreme Court's Ruling (June 18, 2008)

The Supreme Court unanimously dismissed the appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's approach and its conclusion that the Subject's actions constituted a "covered act" under the MTSA.

Purpose of the Medical Treatment and Supervision Act (MTSA):

The Court began by reiterating the objectives of the MTSA: to provide continuous and appropriate medical care and supervision to individuals who have committed serious harmful acts while in a state of legal insanity or diminished capacity. The goals are to improve their mental condition, prevent the recurrence of similar harmful acts, and thereby promote their social reintegration.

The "External and Objective" Standard for Determining "Covered Acts":

The Supreme Court endorsed the High Court's "external and objective" standard for assessing whether an act constitutes a "covered act" under the MTSA, particularly in cases where the individual's actions were driven by severe psychotic symptoms like hallucinations and delusions.

The Court articulated the standard as follows:

In cases such as the present one, where the Subject performed acts based on auditory hallucinations, delusions, etc., due to paranoid schizophrenia, the determination of whether the Subject's conduct constitutes a "covered act" should not be made based on the content of what the Subject perceived due to such hallucinations or delusions.

Instead, the determination should be made from the viewpoint of whether, by externally and objectively considering the Subject's conduct under the circumstances at the time, if a person not in a state of insanity or diminished capacity had committed the same act, it could be evaluated as an act constituting the commission of a covered act, including its subjective elements.

If this can be affirmed, then it can be found that the Subject committed a "covered act."

Rationale for this Standard:

The Supreme Court provided a crucial policy rationale for adopting this objective standard:

"Because, if the applicability of a 'covered act' were to be judged based on the content perceived by the Subject due to such auditory hallucinations, delusions, etc., then the conduct of those persons with severe symptoms who are most in need of medical treatment under the Medical Treatment and Supervision Act might well be found to lack applicability as a 'covered act' in terms of subjective elements, which would be contrary to the purpose of the Act."

In essence, a strict adherence to finding actual, reality-based criminal intent in a severely delusional individual could lead to a paradoxical situation where those most affected by their mental illness (and thus potentially most in need of the MTSA's specialized interventions) would be excluded from its provisions. The objective standard aims to prevent this.

Discussion: Navigating Criminal Intent and Mental Incapacity

This Supreme Court decision grapples with a fundamental tension: how to apply legal definitions of crimes (which typically require a certain mental state, or mens rea) to individuals whose mental state is, by definition, profoundly disturbed and not aligned with objective reality.

- The MTSA's Therapeutic Focus: It's important to remember that the MTSA is not a punitive system. Its primary goal is not to punish but to provide medical treatment, manage risk, and facilitate the social reintegration of individuals who have committed serious harm due to mental incapacity. This therapeutic and public safety orientation heavily influenced the Supreme Court's interpretative approach.

- Sidestepping Complex Criminal Law Debates: The "external and objective" standard allowed the Supreme Court to address the practical needs of the MTSA without delving deeply into contentious theoretical debates within Japanese criminal law regarding the nature of intent (e.g., whether intent is purely a definitional component of a crime – kōsei yōken-teki koi – or also intrinsically linked to culpability/responsibility – sekinin yōso). By focusing on how a "normal person's" actions would be interpreted, the Court found a way to affirm the "covered act" requirement while ensuring the Act's applicability to its target population.

Evaluating the Supreme Court's "External/Objective" Approach

The Supreme Court's pragmatic solution has both benefits and points of contention:

- Benefits:

- Ensuring Access to Treatment: The primary advantage is that it ensures individuals whose harmful actions are a direct manifestation of severe mental illness (and who are consequently found not criminally responsible due to insanity) can be brought within the ambit of the MTSA's specialized treatment and supervision framework. This helps prevent a "gap" in the system where very ill individuals might otherwise receive neither criminal sanctions nor appropriate long-term psychiatric care and risk management.

- Focus on External Harm: It aligns the assessment with the objective harm caused and the external characteristics of the act, which are often what trigger societal concern and the need for intervention.

- Potential Criticisms and Concerns:

- Inferring "Normal" Intent: Legal scholars and practitioners have debated whether it is always straightforward or accurate to infer what a "normal person's intent" would have been based solely on external actions, especially when those actions themselves might be bizarre or heavily influenced by underlying delusional thought processes that are not immediately apparent externally.

- Legal Fiction Argument: Some critics argue that this approach involves a degree of legal fiction by attributing a sane person's mental state and intentions to someone who was, by definition, not operating with a sane mind at the time of the act. This raises questions about the coherence of applying criminal definitions in such a modified way.

- Due Process Considerations: While the MTSA is therapeutic, it still involves a significant deprivation of liberty through compulsory hospitalization and treatment. Therefore, ensuring that the criteria for triggering the Act are applied with due regard for an individual's rights remains crucial. The "external and objective" standard must be applied carefully and consistently to meet due process requirements.

Constitutional Considerations and Due Process

Article 31 of the Japanese Constitution guarantees due process of law. Any system that imposes significant restrictions on personal liberty, even for therapeutic purposes like the MTSA, must adhere to these principles. This includes ensuring that the legal criteria for invoking the MTSA are sufficiently clear and that the process is fair.

The Supreme Court's adoption of the "external and objective" standard can be seen as an attempt to provide a workable and clear definition for "covered acts" within the unique, non-punitive context of the MTSA. However, the debate over whether this standard fully satisfies all due process concerns, or whether further legislative clarification might be beneficial (e.g., by explicitly stating in the MTSA that a lack of reality-based intent due to the underlying mental disorder does not preclude an act from being a "covered act"), continues among legal experts.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's 2008 decision in this case established a vital interpretative rule for the application of the Medical Treatment and Supervision Act. By endorsing an "external and objective" standard for determining whether an act committed by a mentally incapacitated individual qualifies as a "covered act," the Court prioritized the MTSA's core objectives of providing treatment and ensuring public safety. This approach ensures that individuals whose harmful conduct is a direct consequence of severe mental illness, leading to a finding of legal insanity, are not paradoxically excluded from the specialized care the Act is designed to offer simply because their delusional state prevents them from forming criminal intent in the traditional, reality-based sense.

While the ruling offers a pragmatic solution to a difficult legal problem, it also highlights the ongoing challenges and inherent tensions in harmonizing established principles of criminal law with the specific needs and goals of forensic mental health legislation. The decision continues to inform legal practice and scholarly debate regarding the rights and treatment of individuals with severe mental illness who come into contact with the justice system in Japan.