When Public Tax Collection Meets Private Law: Protecting Third Parties in Sales Based on False Property Registrations

Judgment Date: January 20, 1987

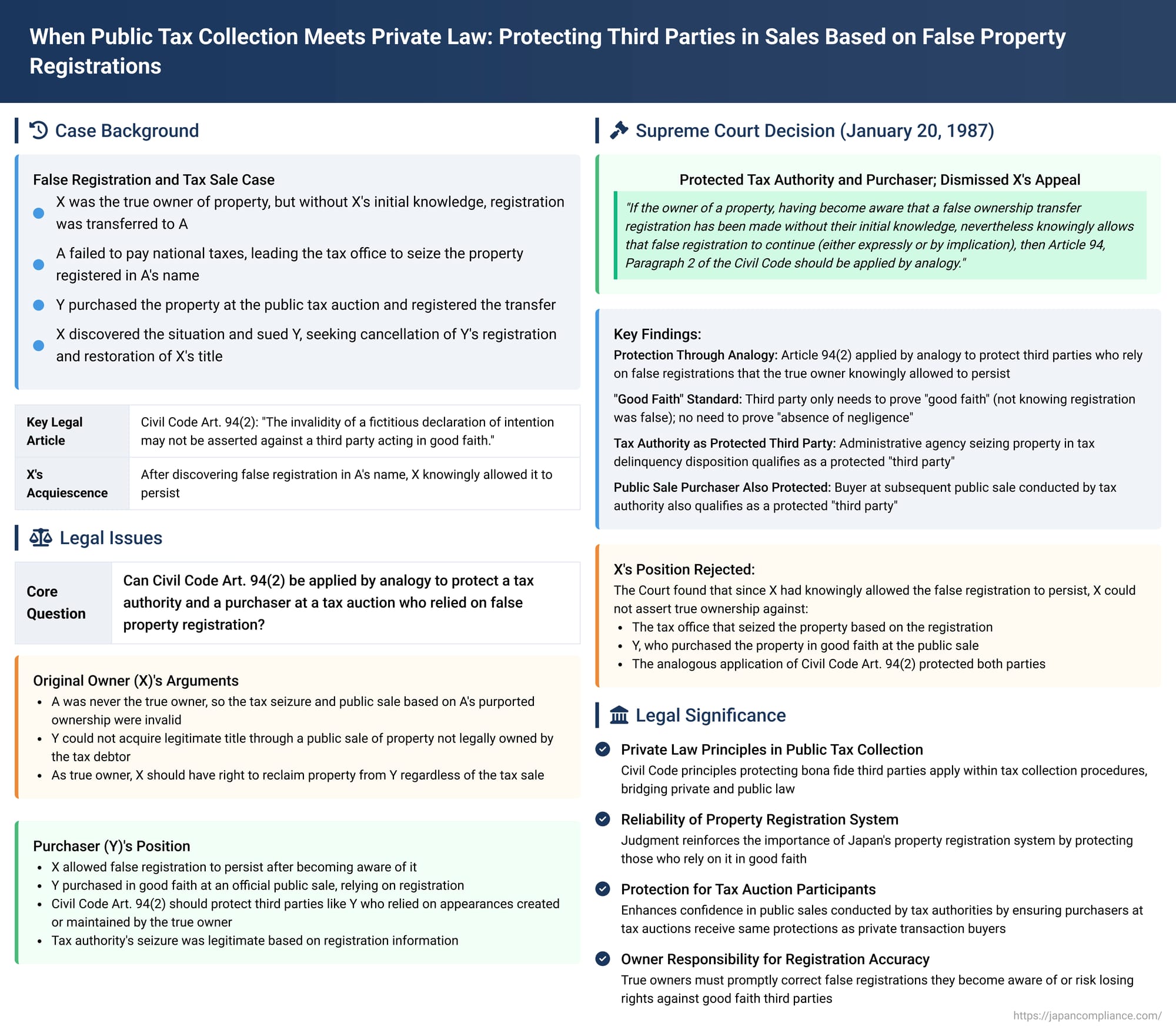

In a significant ruling that underscores the interplay between public tax collection procedures and private law principles, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan affirmed the protection granted to bona fide purchasers at tax auctions, even when the property was sold based on a registration that did not reflect the true ownership, provided the true owner had acquiesced to the false registration. The case hinged on the analogous application of Article 94, Paragraph 2 of the Japanese Civil Code, which safeguards third parties acting in good faith who rely on fictitious declarations of intention.

Background: A Property Lost and a Tax Sale

The plaintiff, X (appellant), was the original and true owner of a parcel of land and a building erected thereon ("the subject property"), and X duly held the ownership registration. However, at some point, without X's initial knowledge, an ownership transfer registration for the subject property was made in the name of an individual, A.

Subsequently, A became delinquent in the payment of national taxes. As a result, the Director of the Okinawa National Tax Office, B (a participating party in the lawsuit), initiated a tax delinquency disposition against A. As part of this process, B seized the subject property—which was registered in A's name—and an official seizure registration was made. Following the seizure, the tax office conducted a public sale (kōbai) of the subject property to satisfy A's unpaid taxes. At this public sale, Y (defendant, appellee) purchased the subject property and completed the ownership transfer registration into Y's name.

Upon discovering these events, X filed a lawsuit against Y, seeking the cancellation of the ownership transfer registration made to Y and the restoration of X's registered title. X's fundamental argument was that since A was never the true owner, the public sale based on A's purported ownership was invalid, and therefore Y could not have acquired legitimate title. (X had initially also sought a declaration from the court that the public sale itself was invalid against the tax office chief, B, but this part of the claim was later withdrawn).

Y, the purchaser, countered by arguing that even if A was not the true owner at the time of the public sale, Y had validly acquired ownership. Y's defense rested on the analogous application of Article 94, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code. This provision typically protects a third party who, in good faith, relies on a fictitious transaction or declaration of intention made by two other colluding parties. Y contended that X, by knowingly allowing the false registration in A's name to persist, had created a misleading appearance of ownership upon which Y, as a bona fide purchaser at the public sale, had relied.

The appellate High Court had ruled against X, prompting X to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Core Legal Issue: Applying Civil Code Protections in a Tax Collection Context

The central question before the Supreme Court was whether Article 94, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code could be applied by analogy to protect both the tax authority (which seized the property based on the registration in A's name) and the purchaser (Y) at the subsequent public sale, especially when the true owner (X) had become aware of the false registration but allowed it to continue.

Civil Code Article 94, Paragraph 2 states: "The invalidity of a fictitious declaration of intention referred to in the preceding paragraph may not be asserted against a third party acting in good faith."

Paragraph 1 of Article 94 deals with a fictitious declaration of intention made by a party in collusion with another party, which is deemed null and void between those parties. The "analogous application" (ruisui tekiyō) of Paragraph 2 extends its protective reach beyond direct collusion cases. It can apply to situations where a true owner, even if not initially part of creating the false appearance, becomes aware of an incorrect or false registration in another person's name and, through their subsequent conduct (expressly or implicitly acquiescing to it), allows this misleading public record to persist.

The Supreme Court's Reasoning and Decision

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, affirming the High Court's decision. The Court's reasoning was rooted in established principles regarding the protection of third parties who rely on the public record of property registrations.

Analogous Application of Civil Code Article 94, Paragraph 2

The Court first reiterated a key principle: If the owner of a property, having become aware that a false ownership transfer registration has been made without their initial knowledge, nevertheless knowingly allows that false registration to continue (either expressly or by implication), then Article 94, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code should be applied by analogy.

This means that the true owner may be prevented from asserting their underlying true ownership against a third party who has acted in reliance on the false registration.

Requirements for Third-Party Protection

The Court then clarified the conditions a third party must meet to receive protection under this analogous application:

- The third party needs to allege and prove their "good faith" (善意 - zen'i). In this context, good faith means they were unaware that the registration was false or that the registered person was not the true owner.

- Crucially, the third party does not need to allege and prove that their good faith was also "without negligence" (無過失 - mukashitsu). A mere showing of good faith (i.e., lack of knowledge of the true state of affairs) is sufficient. The Supreme Court cited several of its own precedents supporting this interpretation.

Defining a "Third Party" in this Context

The Court defined a "third party" eligible for protection under Article 94, Paragraph 2 (and its analogous application) as:

Someone other than the parties directly involved in creating the false appearance (or their general successors in interest) who has subsequently acquired a legal interest concerning the object of that false display (in this case, the property).

Tax Authority and Public Sale Purchaser Qualify as Protected "Third Parties"

This was a critical part of the ruling for the specific facts of the case. The Supreme Court explicitly held that both:

- The administrative agency (the tax authority) that seizes the registered property as part of a tax delinquency disposition against the person named in the (false) registration, AND

- The purchaser who buys the property at the subsequent public sale conducted by the tax authority,

qualify as "third parties" for the purposes of protection under Article 94, Paragraph 2. The Court referenced several of its past decisions, including a significant 1956 ruling (Showa 31.4.24), which supported this position. This earlier case had established that the State, when seizing property in a tax delinquency disposition, is in a position analogous to a seizing creditor in a civil execution and should not be treated less favorably than a private creditor regarding reliance on property registrations.

Application to X's Case

The Supreme Court found that the High Court's factual findings were adequately supported by the evidence presented. While the Supreme Court's judgment text itself does not detail these specific findings, they would have pertained to X's knowledge and subsequent acquiescence to the false registration in A's name, and to Y's good faith as a purchaser.

Based on these established facts (as determined by the High Court), the Supreme Court concluded that the High Court's legal judgment was correct: X could not assert their true ownership against the participating tax office chief (B) or against the purchaser (Y). The analogous application of Civil Code Article 94, Paragraph 2, protected Y's acquisition of title through the public sale.

Therefore, X's appeal was dismissed, and Y's ownership, obtained through the tax auction, was upheld.

Significance and Implications of the Ruling

This 1987 Supreme Court decision carries several important implications for the intersection of tax law and private law:

- Reinforcement of Private Law Principles in Public Law Contexts: The judgment strongly affirms that principles from private law, such as the protection of bona fide third parties who rely on false appearances of title (as embodied in Civil Code Article 94, Paragraph 2), are applicable within public law spheres, including tax collection procedures and public sales conducted by tax authorities.

- Protection for Tax Authorities and Public Sale Purchasers: It clarifies that both the seizing tax authority and an innocent purchaser at a tax auction can be shielded by these private law protections if the true owner has, by their conduct, allowed a false registration to persist. This promotes confidence in the reliability of public sales conducted by tax authorities.

- Emphasis on the Public Register: The ruling underscores the legal importance of property registration in Japan. The policy of protecting those who rely in good faith on the public register extends even to situations where the underlying basis for the registration (A's purported ownership) was flawed, provided the true owner's acquiescence contributed to the misleading state of affairs.

- Standard of "Good Faith": The decision reiterates that for a third party to gain protection under Article 94, Paragraph 2, the standard is "good faith" (lack of knowledge of the defect in title), and the more stringent requirement of "absence of negligence" is not imposed on the third party.

- Nature of Tax Claims: While not the central focus of this specific judgment's text, this case fits into a broader jurisprudential trend where Japanese courts, in the absence of specific overriding tax statutes, tend to apply general private law principles to the enforcement of tax claims. Earlier Supreme Court cases had already established that the State, in tax collection, is often in a position analogous to a private creditor and can benefit from rules like those governing the registration of property rights. While some early cases mentioned a "public interest" element in upholding the integrity of public sales, later cases, including this one, focus more directly on applying the established private law doctrines regarding reliance on false appearances.

This case serves as a clear reminder to property owners of the importance of diligently monitoring their property registrations and taking prompt action to correct any inaccuracies. Failure to do so, particularly if one becomes aware of a false registration and allows it to continue, can lead to the irreversible loss of property to a bona fide third party, even if that party acquires the property through a tax sale initiated against the falsely registered owner. It highlights the balance the law strikes between protecting true ownership and safeguarding the security of transactions and the reliability of public records.