When Public Permission Meets Private Contracts: A 1961 Supreme Court Ruling on Agricultural Land Sales

Judgment Date: May 26, 1961

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

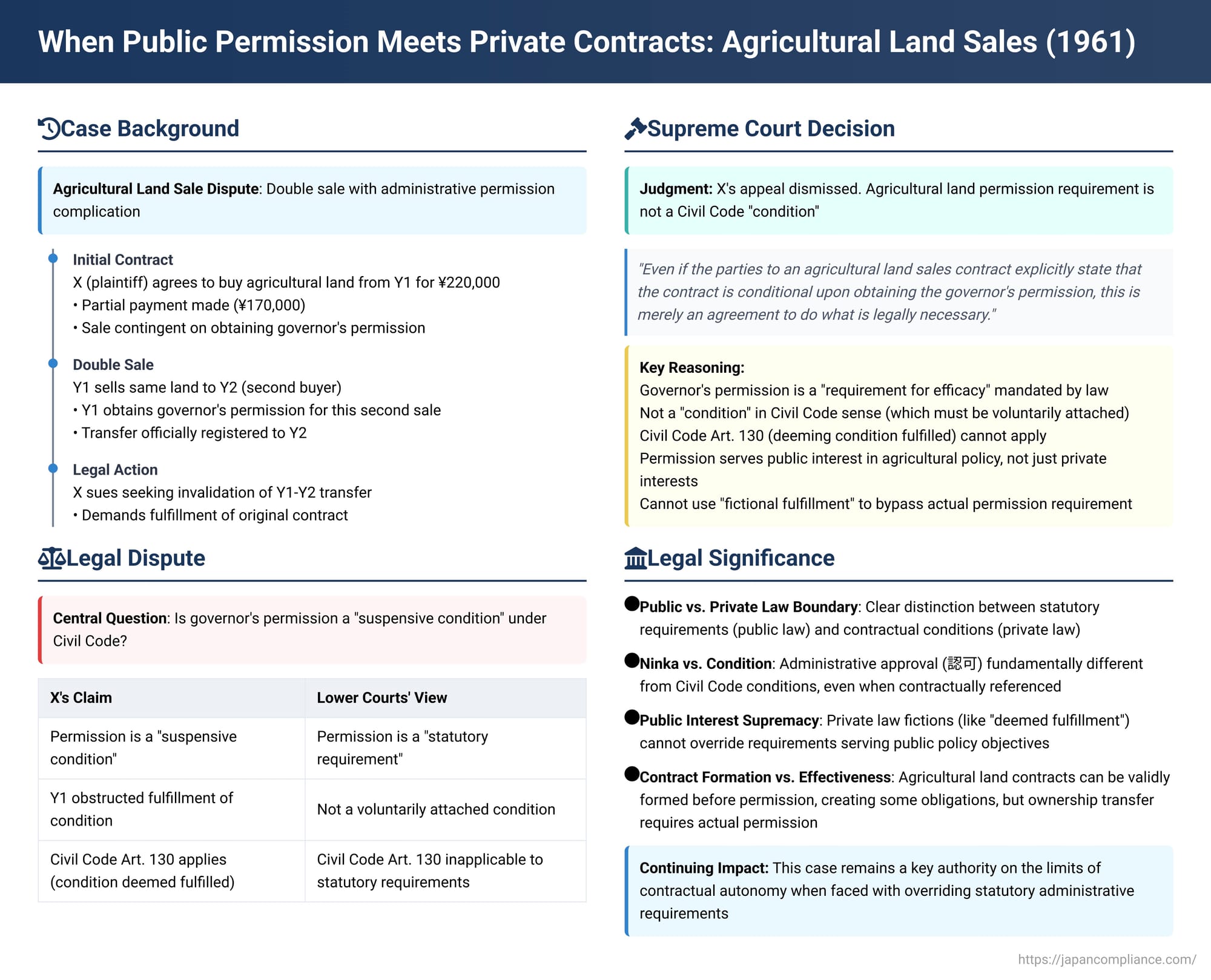

Contracts for the sale of agricultural land in Japan operate under a special legal framework, primarily governed by the Agricultural Land Act. This Act mandates permission from a public authority (historically the prefectural governor, now generally the local Agricultural Committee) for the transfer of such land. A 1961 Supreme Court decision delved into the complex interplay between this statutory permission requirement and the general principles of contract law found in the Civil Code, particularly those concerning "conditional legal acts." The Court clarified that this mandatory public permission is not a "condition" in the way private parties might attach conditions to their agreements, and its absence cannot be overcome by certain Civil Code provisions designed for party-stipulated conditions.

The Double Sale and the Disputed Permission: A Farmer's Predicament

The case involved X (the plaintiff), who entered into an agreement with Y1 (the defendant seller) to purchase agricultural land, including both ownership and cultivation rights. The agreed price was 220,000 yen. A crucial part of their agreement was that the sale was contingent upon obtaining the prefectural governor's permission, as required by Article 3 of the Agricultural Land Act then in force. X paid a significant portion of the purchase price (170,000 yen) immediately, with the understanding that the remaining balance would be paid once the governor's permission was secured and the ownership transfer was formally registered.

However, the situation became complicated. Y1 subsequently entered into another sales contract for the very same agricultural land with a different buyer, Y2 (another defendant). Y1 then proceeded to obtain the governor's permission for this second sale to Y2 and completed the official registration of ownership transfer in Y2's name.

Feeling wronged, X initiated a lawsuit. He sought, among other things, a court declaration that the transfer procedures between Y1 and Y2 were invalid. He also demanded that Y1 fulfill their original agreement by obtaining the necessary permission for the sale to X and then completing the ownership transfer registration to him.

Lower Courts' Views on the "Condition"

- The First Instance court (Matsuyama District Court, Saijo Branch) dismissed X's claim.

- X appealed to the Takamatsu High Court. In the appeal, X argued that the sales contract with Y1 was a "conditional legal act" (jōken-tsuki hōritsu kōi) in the sense of the Civil Code, with the governor's permission acting as a "suspensive condition" (停止条件 - teishi jōken) – meaning the contract's main effect (transfer of ownership) was suspended until the condition (permission) was fulfilled. X contended that Y1 had a legal obligation to cooperate in obtaining this permission but had failed to do so. Furthermore, X claimed that Y1's act of selling the land to Y2 constituted an obstruction of the fulfillment of X's condition, which would typically engage provisions of the Civil Code. Specifically, X invoked Civil Code Article 130, which (in certain circumstances where a party whose interests are negatively affected by the non-fulfillment of a condition improperly obstructs its fulfillment) allows the condition to be "deemed fulfilled." X argued that, based on this principle, the governor's permission for his purchase should be considered as having been obtained, thus validating his claim to the land.

The High Court, however, rejected X's arguments. It distinguished between conditions voluntarily attached by parties to a contract (as envisaged by Civil Code Articles 127 et seq.) and requirements imposed by law. The High Court defined a "condition" under the Civil Code as an adjunct to a legal act that makes its efficacy (coming into effect or ceasing to be effective) dependent on the occurrence or non-occurrence of a future, uncertain event, implying that such conditions must be set by the free will of the contracting parties. In contrast, the governor's permission for agricultural land sales was characterized as a "legal requirement for the efficacy of the legal act" (hōritsu kōi no kōryoku hassei yōken). The court reasoned that even if one were to call such legally mandated prerequisites "statutory conditions" (hōtei jōken), they do not fall under the category of "conditions" regulated by Civil Code Articles 127 et seq. Therefore, the parties' agreement to make their contract conditional on obtaining the governor's permission was merely an affirmation of a step that was already legally indispensable; it did not transform the contract into a "suspensive conditional legal act" in the Civil Code sense. Consequently, the High Court dismissed X's appeal.

X further appealed to the Supreme Court, maintaining that the High Court had erred in its interpretation of conditional legal acts under the Civil Code.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Permission as a "Statutory Requirement," Not a Civil Code "Condition"

The Supreme Court, in its judgment on May 26, 1961, dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision but with more detailed reasoning on the specific application of Civil Code provisions.

1. Not a "Suspensive Conditional Legal Act"

The Supreme Court concurred with the High Court's fundamental position:

- A legal act aimed at transferring ownership of agricultural land does not produce any legal effect unless and until the prefectural governor's permission is obtained, as stipulated by the Agricultural Land Act (Article 3, Paragraph 4, under the then-current Act).

- The governor's permission is a "requirement for the efficacy of the legal act."

- Therefore, even if the parties to an agricultural land sales contract explicitly state that the contract is "conditional" upon obtaining the governor's permission, this "is merely an agreement to do what is legally necessary." It does not convert the sales contract into what is known in Civil Code terms as a "suspensive conditional legal act."

2. Civil Code Article 130 (Deeming Condition Fulfilled) Inapplicable to this Statutory Requirement

The Supreme Court then addressed the crucial argument regarding Civil Code Article 130, which allows a condition to be "deemed fulfilled" if a party improperly obstructs its fulfillment.

- The Court stated that even if one were to assume, for argument's sake, that some Civil Code provisions concerning conditions could be applied by analogy to "statutory conditions" (like the governor's permission) where their nature permits, this would not help X in this case.

- The High Court was correct in concluding that, regarding the agricultural land sales contract between X and Y1, even if Y1 had engaged in acts that obstructed the "fulfillment of the condition" (i.e., obtaining the governor's permission for X), Civil Code Article 130 could not be applied to deem the contract effective and thereby make X the owner of the land.

- The underlying reason for this is paramount: "the sale of agricultural land requires the governor's permission based on public interest." As long as the governor's permission is, in reality, absent for X's purchase, the transfer of ownership cannot take effect. This is the clear mandate of Article 3 of the Agricultural Land Act.

- Therefore, "it is not permissible by nature to determine the effect of such an agricultural land ownership transfer through a fictional effect attached to the parties' intentions, such as the 'deeming' provision of Civil Code Article 130." The public interest embedded in the statutory permission process cannot be overridden by a private law fiction based on party conduct.

Unpacking the Legal Concepts: Public Interest in Farmland Reigns Supreme

This Supreme Court decision is a foundational ruling on the interaction between mandatory administrative approvals and private contractual arrangements in Japan.

Agricultural Land Act: Protecting Public Interest in Farmland

The Agricultural Land Act imposes strict controls on the transfer of rights in agricultural land. Its primary objectives include preserving the outcomes of post-World War II land reforms (which aimed to create a system of owner-cultivators), preventing speculative ownership of farmland, ensuring that land passes to those who will cultivate it properly and efficiently, and thereby promoting overall agricultural productivity. The requirement for permission from the Agricultural Committee (formerly the governor) for sales and other transfers (with limited exceptions) is the cornerstone of this regulatory regime. Any transfer made without this permission is legally void. The application for permission generally needs to be a joint submission by the parties involved.

"Approval" (Ninka) in Administrative Law vs. Civil Code "Conditions"

The type of administrative permission required under the Agricultural Land Act is often classified by legal scholars as a ninka (認可 – approval or ratification). A ninka is an administrative act that bestows full legal effect upon a private law act (like a contract) that would otherwise be incomplete or ineffective. This is distinct from a kyoka (許可 – permit), which typically lifts a general prohibition on a certain activity. In the case of agricultural land sales, the contract between the buyer and seller is generally considered to be validly formed even before the ninka is obtained. This initial contract creates certain obligations between the parties, such as the seller's duty to cooperate with the buyer in the application process for the ninka. The actual transfer of ownership rights, however, only becomes effective upon the granting of the ninka.

This is fundamentally different from "conditions" as understood in Civil Code Articles 127 et seq. Civil Code conditions are stipulations voluntarily attached by the contracting parties to make the effect of their agreement dependent on some future, uncertain event. While the outcome of a ninka application is also a future uncertain event, the requirement for the ninka itself is not a matter of party volition but a mandate of public law.

The Supreme Court's decision firmly established that merely agreeing to obtain a legally required ninka does not transform that requirement into a "suspensive condition" under the Civil Code. The parties are simply acknowledging a pre-existing legal necessity.

Why a Party Cannot "Deem" Government Permission to be Granted

The most critical part of the ruling is its rejection of the analogous application of Civil Code Article 130 to the ninka requirement. Article 130 allows a condition to be fictionally "deemed fulfilled" if its fulfillment is improperly obstructed by a party who would be disadvantaged by its occurrence. This provision is designed to protect the good faith expectations of parties in private contractual settings.

However, the Supreme Court reasoned that the ninka for agricultural land sales serves a vital public interest. The decision to grant or withhold permission is made by a public authority based on considerations of agricultural policy, not on the private wishes or conduct of the contracting parties alone. To allow one party to "deem" this public permission obtained simply because the other party acted obstructively would undermine the entire statutory scheme and the public interests it is designed to protect. The actual, substantive approval by the competent public authority cannot be bypassed by a private law fiction.

Implications of the Ruling

This 1961 judgment clearly demarcated the boundary between private contractual autonomy and overriding public law requirements. It established that:

- Legally mandated administrative approvals, like the permission for agricultural land sales, are not "conditions" in the Civil Code sense, even if parties refer to them as such.

- Private law mechanisms like Civil Code Article 130, which allow for the fictional fulfillment of conditions due to party misconduct, cannot be used to circumvent the need for actual administrative approval when that approval is required for reasons of public interest.

It is worth noting, as legal commentators have pointed out, that even if the buyer (X) could not "deem" the permission obtained to secure the land itself, he might still have other potential claims against the seller (Y1) for breach of the contractual duty to cooperate in the permission process, potentially leading to a claim for damages. This specific judgment, however, focused on the impossibility of compelling the transfer of ownership without actual public permission.

Conclusion: The Distinct Nature of Legally Mandated Administrative Approvals

The Supreme Court's decision underscores the distinct nature of administrative approvals required by law for private transactions, especially when those approvals serve significant public policy objectives. While parties are free to structure their contracts and attach their own conditions, they cannot use private law doctrines to bypass or fictionally satisfy fundamental legal requirements imposed by statutes like the Agricultural Land Act. The integrity of such regulatory schemes, designed to protect broader public interests, takes precedence. This case remains a key authority in understanding the limits of contractual autonomy when faced with overriding statutory mandates involving administrative oversight.