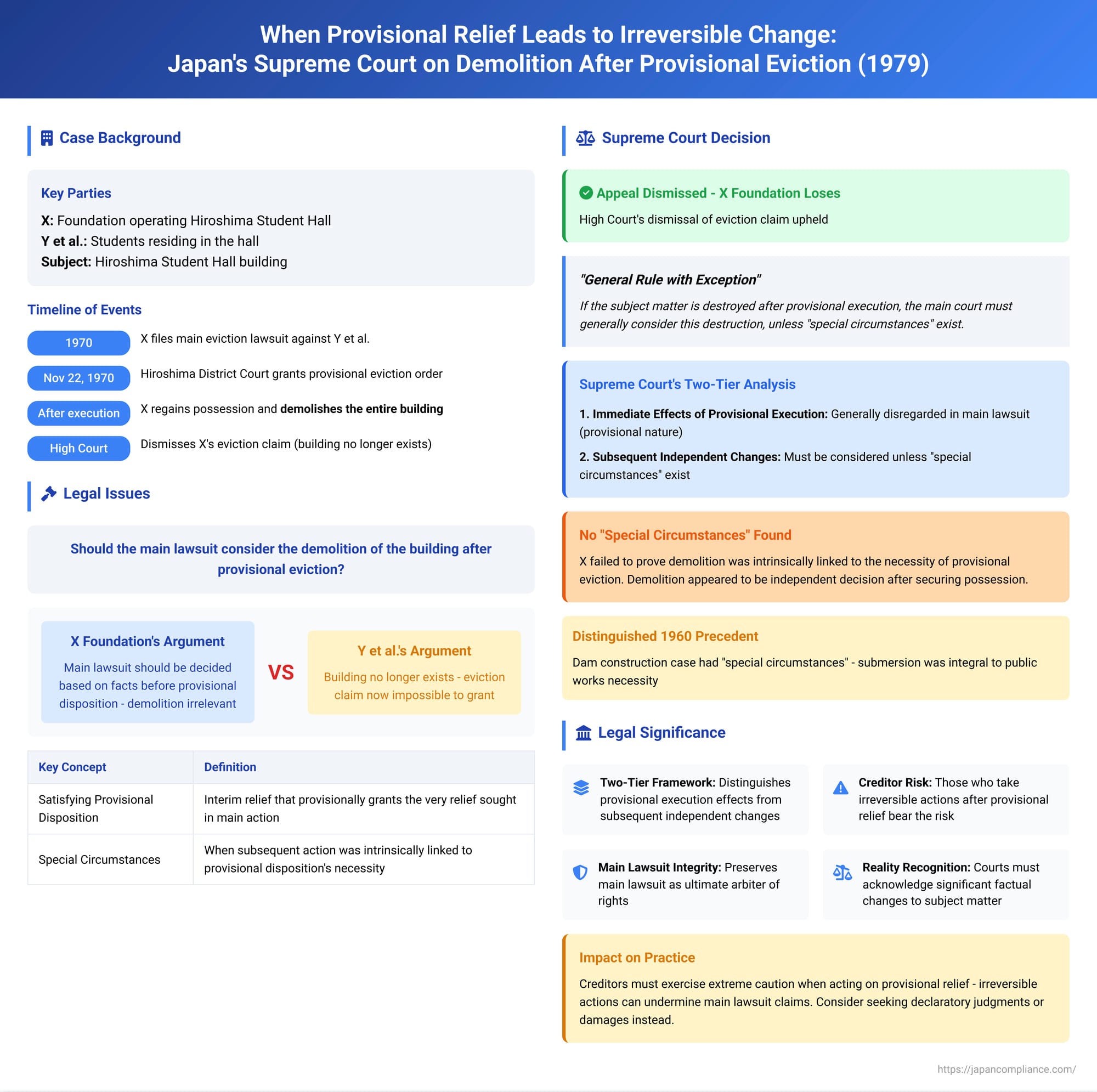

When Provisional Relief Leads to Irreversible Change: Japan's Supreme Court on Demolition After Provisional Eviction and Its Impact on the Main Case

Date of Supreme Court Decision: April 17, 1979

Provisional remedies, such as a "provisional disposition to determine a provisional status" (仮の地位を定める仮処分 - kari no chii o sadameru karishobun), are designed to offer swift, temporary protection of a creditor's rights pending the outcome of a full lawsuit. Sometimes, these remedies can be "satisfying" (満足的仮処分 - manzoku-teki karishobun), meaning they provisionally grant the creditor the very relief sought in the main action—for example, ordering the eviction of occupants from a property. A critical question arises when the creditor, after enforcing such a provisional disposition, takes further, irreversible actions, such as demolishing the property in question. How do these subsequent actions impact the ongoing main lawsuit? A 1979 Supreme Court of Japan decision (Showa 51 (O) No. 937) provided a nuanced answer, balancing the provisional nature of interim relief with the realities of irreversible factual changes.

The Factual Background: Student Hall Eviction and Demolition

The case involved X, a foundational juridical person that provided student accommodation in its Hiroshima Student Hall, and Y et al., students residing in the hall.

- The Dispute and Main Lawsuit: X foundation claimed that the occupancy of Y et al. in the student hall was illegal and initiated a lawsuit for their eviction (the "main lawsuit").

- Provisional Disposition for Eviction: While this main eviction lawsuit was pending, X obtained a provisional disposition order from the Hiroshima District Court on November 22, 1970. This order, based on X's asserted ownership rights, mandated the eviction of Y et al. from the student hall. This was a "satisfying" provisional disposition as it temporarily achieved X's primary litigation goal.

- Execution and Subsequent Demolition: X proceeded to execute this provisional disposition, successfully regaining possession of the student hall from Y et al. Immediately thereafter, X demolished the entire student hall building.

- Lower Court Proceedings in the Main Lawsuit:

- The Hiroshima District Court (court of first instance) initially ruled in favor of X in the main lawsuit, upholding the eviction claim.

- Y et al. appealed to the Hiroshima High Court. A key argument on appeal was that the building, the very subject of the eviction claim, no longer existed due to X's demolition.

- X countered that the main lawsuit should be decided based on the facts as they stood before the provisional disposition was executed and the building demolished. X argued that the court should not take into account factual changes brought about by the enforcement of the provisional order or subsequent related actions.

- The Hiroshima High Court reversed the District Court's decision and dismissed X's eviction claim. It reasoned that the subject matter of the claim—the building—had been destroyed and therefore an eviction order was no longer tenable.

X foundation then appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Conundrum: Does the Main Lawsuit Ignore Post-Provisional Changes?

The central legal question was whether the demolition of the student hall by X, after X had regained possession through a provisional eviction order, should be considered by the court when deciding the merits of X's original eviction claim in the main lawsuit. X's position was that such subsequent events were irrelevant to the underlying right to evict.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Balancing Provisionality with Supervening Reality

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of April 17, 1979, dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision to dismiss the eviction claim. The Court's reasoning carefully distinguished between the immediate effects of a provisional disposition's execution and significant, subsequent factual changes.

- General Rule Regarding the Effect of Provisional Execution on the Main Lawsuit:

The Court acknowledged a general principle: the factual state created merely by the execution of a provisional disposition itself is, by its nature, provisional and temporary. Therefore, this altered state of affairs (e.g., the fact that Y et al. were no longer physically in the building due to the provisional eviction) should, in principle, not be taken into account by the court when adjudicating the merits of the underlying claim in the main lawsuit. The main lawsuit is intended to definitively determine the parties' substantive rights as they existed, irrespective of the interim provisional measures. This part of the reasoning was consistent with an earlier Supreme Court precedent from 1960. - Crucial Distinction for Subsequent and Independent Factual Changes:

However, the Supreme Court drew a critical distinction for new factual changes that occur after the execution of a provisional disposition, particularly when these changes are brought about by the creditor and fundamentally alter the subject matter of the dispute. - The Rule for Post-Execution Destruction of the Subject Matter:

The Court held that if, after a provisional disposition has been executed, the subject matter of the preserved right (in this case, the student hall building) is destroyed, the court adjudicating the main lawsuit must generally take this subsequent destruction into account when determining the outcome of the claim. - The "Special Circumstances" Exception:

This general rule—that subsequent destruction must be considered—applies unless "special circumstances" (特別の事情 - tokubetsu no jijō) exist. Such special circumstances would be present if:- The creditor's act of causing the factual change (e.g., demolition of the building) was intrinsically linked to, and formed a necessary basis for, the original justification and necessity of the provisional disposition itself. For example, if the building was an imminent danger requiring immediate demolition, and the provisional eviction was a necessary prelude to that urgent demolition.

- And, in reality, the creditor carried out this fundamental change (demolition) as a direct, immediate, and integral follow-up to the execution of the provisional disposition, making the demolition substantively part of what the provisional disposition was intended to achieve or enable.

- Application to the Current Case:

- X foundation obtained the provisional eviction order and, after regaining possession, demolished the building.

- Critically, X did not allege or prove any such "special circumstances." There was no evidence presented that the demolition was urgently required for safety reasons that underpinned the necessity of the provisional eviction itself, or that the provisional order implicitly contemplated or necessitated the immediate demolition as part of its core purpose. The demolition appeared to be an independent decision and action taken by X after it had secured possession through the provisional remedy.

- Therefore, the "special circumstances" exception did not apply. The general rule—that the court in the main lawsuit must consider the subsequent destruction of the building—prevailed.

- Outcome of the Main Lawsuit:

Since the student hall, the subject matter of X's eviction claim, no longer existed at the time of the High Court's decision (and the Supreme Court's review), X's claim for an order to evict Y et al. from that specific building had become moot or impossible to grant. The High Court's decision to dismiss X's claim was therefore affirmed as correct in its conclusion. - Distinguishing the 1960 Precedent:

The Supreme Court explicitly distinguished its current ruling from its 1960 decision (Supreme Court, First Petty Bench, February 4, 1960, Minshu Vol. 14, No. 1, p. 56). In the 1960 case, a provisional disposition had ordered the removal of a building from land that was urgently needed for dam construction, which would lead to the land's submersion. The subsequent submersion of the land (and thus the effective destruction of the building's utility in that location) was considered to be an integral part of the necessity and purpose of the provisional disposition. The urgent public works project provided the "special circumstances." X's demolition of the student hall in the present case lacked such an intrinsic, justifying link to the grounds upon which the provisional eviction order was granted.

Implications and Analysis

This Supreme Court decision offers important clarifications on the complex relationship between satisfying provisional dispositions and the main lawsuit:

- Nature of "Satisfying Provisional Dispositions": These are potent interim remedies that grant the creditor, on a provisional basis, the substantive relief sought in the main action (e.g., possession of property, cessation of an activity). While effective in the short term, their provisional nature means they do not replace the need for a definitive judgment on the merits in the main lawsuit.

- Provisionality and the Main Lawsuit: The core principle that civil provisional remedies are temporary and ancillary to the main lawsuit is upheld. The mere execution of a provisional order does not dictate the outcome of the main lawsuit regarding the underlying rights of the parties. The main lawsuit is where those rights are finally determined.

- Factual State Created by Provisional Execution vs. Subsequent Factual Changes:

- The immediate factual state created by the provisional disposition's execution (e.g., Y et al. being physically removed from the Hiroshima Student Hall) is generally not considered by the main court in deciding whether X had the right to evict them. The right itself is what's at issue.

- However, this decision makes it clear that if the creditor, after enforcing the provisional remedy, independently creates a new, significant, and often irreversible factual state (like demolishing the very building they are suing to recover), this new state of affairs is generally relevant to the main lawsuit. The lawsuit cannot proceed as if this fundamental change never occurred.

- Risk Borne by the Creditor: A creditor who takes drastic and irreversible actions, such as demolishing a building after obtaining possession through a provisional order, does so at their own risk. If they ultimately lose the main lawsuit (i.e., if it is determined that they had no legal right to evict or repossess), they could face substantial liabilities for wrongful execution of the provisional remedy and for the destruction of the property.

- Scholarly Discussions: Legal commentary surrounding such cases often discusses the appropriate course for a plaintiff in the main lawsuit when such irreversible changes occur. While the original claim (e.g., for eviction from a now-nonexistent building) may become untenable, the plaintiff might need to consider amending their claim to seek, for example, a declaratory judgment confirming their rights as they existed at the time of the provisional order, or damages for unlawful occupation up to that point, rather than persisting with a claim for physically impossible relief.

- No "Special Circumstances" in this Case: X's failure to demonstrate that the demolition was an integral and necessary component of the provisional relief sought was fatal to its argument that the demolition should be disregarded. The act appeared to be a separate decision made after possession was secured.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's April 17, 1979, decision carefully navigates the interplay between the temporary relief afforded by provisional dispositions and the definitive adjudication sought in the main lawsuit. It establishes a two-tiered approach:

- The immediate factual consequences flowing directly from the execution of a "satisfying" provisional disposition are generally disregarded when the main court assesses the underlying legal rights.

- However, significant new factual changes to the subject matter, particularly irreversible ones like destruction, brought about by the creditor after the execution of the provisional order, will generally be taken into account by the main court, unless those changes were so intrinsically linked to the necessity and purpose of the provisional order itself as to constitute "special circumstances."

This ruling underscores the caution that creditors must exercise when acting upon the strength of a provisional disposition. While such orders provide crucial interim protection, any subsequent, independent actions that irreversibly alter the subject matter of the dispute can have profound consequences for the viability of their claims in the main lawsuit. The decision reinforces the integrity of the main lawsuit as the ultimate arbiter of rights, while acknowledging that real-world events subsequent to provisional measures cannot always be ignored.