When Promises Fade: Government Policy Shifts and Business Reliance in Japan – The 1981 Factory Inducement Case

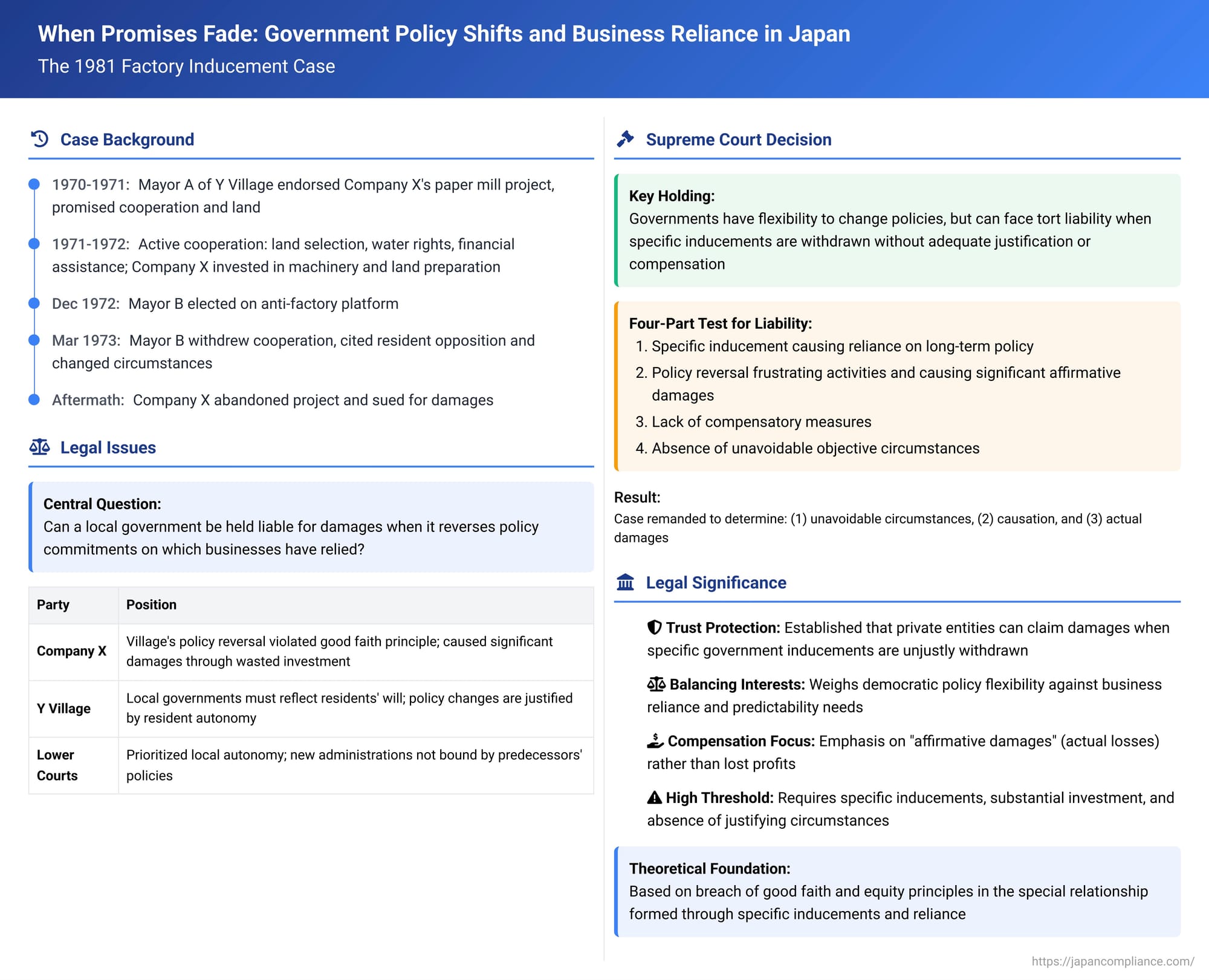

Governments often seek to attract businesses through various incentives and policy commitments. But what happens when a new administration, reflecting a shift in public sentiment or priorities, reverses those commitments after a company has already invested significantly? A pivotal judgment by the Supreme Court of Japan on January 27, 1981, addressed this complex scenario, establishing important principles for the protection of trust (shinrai no hogo) in relationships between government entities and private businesses.

The Factual Background: A Factory Project and a Political Shift

The case originated in Y Village, located in Okinawa Prefecture, which at the time of the initial events was under the administration of the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands before its reversion to Japan in May 1972.

- Initial Plan and Village Endorsement (1970-1971): In November 1970, Company X developed plans to construct a paper mill within Y Village. Company X petitioned Mr. A, who was the mayor of Y Village at the time, to support the factory's establishment and to arrange for the transfer of village-owned land to be used as part of the factory site. Following a resolution by the village council, Mayor A officially agreed to attract the factory and provide the land. In March 1971, Mayor A explicitly promised Company X the village's full cooperation in the factory's construction.

- Active Cooperation and Investment (1971-1972): A period of active cooperation followed. The factory site was selected through joint efforts. Company X bore the financial responsibility for compensating existing cultivators on the chosen land. Mayor A provided a formal letter of consent for Company X's application for necessary water rights (then managed by the US Civil Administration). Furthermore, when Company X was preparing to order machinery, Mayor A assisted by sending a letter to financial institutions, urging them to facilitate loans for Company X's equipment purchases. Relying on these commitments and active support, by December 1972, Company X had placed orders for the required machinery and had completed the necessary land preparation work for the factory site.

- Shift in Village Leadership and Policy (1972-1973): Around the same time, in December 1972, a mayoral election was held in Y Village. The incumbent, Mayor A, was defeated by Mr. B, who assumed office as the new mayor in January 1973. Mayor B had garnered support from local residents who were opposed to the paper mill's construction and, upon taking office, adopted a stance against the project.

- Withdrawal of Cooperation: Mayor B's administration took concrete steps to halt the project. When Company X submitted its building permit application in accordance with Okinawa's then-current building regulations, Mayor B, contrary to procedural requirements, did not forward the application to the designated prefectural building official. On March 29, 1973, Mayor B officially notified Company X of the village's disagreement with the building permit application. The reasons cited included opposition from residents near the proposed factory site, significant changes in social conditions since the initial village council resolution to attract the factory, and concerns that the factory might impede future regional development. The judgment text also notes that the existence of a planned agricultural dam upstream of the factory site was mentioned as a reason by Mayor B.

- Project Abandonment and Lawsuit: Faced with this complete withdrawal of cooperation from Y Village, Company X concluded that the construction and operation of the factory had become impossible and was forced to abandon the project. Company X subsequently filed a lawsuit against Y Village, seeking compensation for the damages incurred due to this policy reversal. The claim was primarily based on tort liability under Article 709 of the Civil Code, alleging that the village's change in policy violated the principle of good faith, and also, separately, under Article 1 of the State Compensation Act for Mayor B's failure to forward the building permit application.

Lower Courts: Prioritizing Local Autonomy

The lower courts were not sympathetic to Company X's plight:

- The Naha District Court (first instance) dismissed Company X's claim. It reasoned that local public entities are established to promote the welfare of their residents and must operate in accordance with the residents' will. Therefore, if a local government's policy to attract businesses is subsequently changed due to shifts in resident opinion or the election of a new administration with a different mandate, the company cannot demand that the new leadership uphold the expectations created by the previous one. The court found that the new administration's refusal to cooperate did not violate the principle of good faith or other similar legal principles.

- The Fukuoka High Court, Naha Branch (second instance) upheld the District Court's decision, employing similar reasoning.

Company X appealed this outcome to the Supreme Court of Japan. (The part of the appeal concerning Mayor B's failure to forward the building permit was dismissed by the Supreme Court on procedural grounds, due to the late submission of reasons for appeal, and is not the focus here).

The Supreme Court's Decision: Balancing Policy Flexibility with Protection of Trust

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of January 27, 1981, took a more nuanced approach, partially reversing the High Court's decision and remanding the case for further consideration.

Government's Right to Change Policy

The Court began by acknowledging a fundamental aspect of public administration:

- The "principle of resident autonomy" (jūmin jichi no gensoku), which dictates that the policies of a local public entity should be conducted based on the will of its residents, is a basic principle of local government organization and operation.

- Furthermore, even when a local government, as an administrative body, decides on a policy intended to be continuous over the future, it is natural for such policies to be subject to change due to evolving social conditions or other factors. As a general rule, a local government is not rigidly bound by its previous policy decisions.

When Trust Warrants Legal Protection

However, the Supreme Court established that this governmental flexibility is not absolute, particularly when specific commitments have been made to private parties:

- The Court stated that a different situation arises if the local government's decision goes beyond merely establishing a general ongoing policy and involves individual, specific recommendations or inducements (kobetsuteki, gutaiteki na kankoku naishi kan'yū) directed at a particular entity, encouraging it to undertake specific activities that align with the stated policy.

- This is especially relevant if the nature of the activity is such that it requires the continuation of that policy for a considerably long term to yield results commensurate with the capital or labor invested by the private entity.

- In such scenarios, it is typical for the specific entity to rely on the understanding that the policy will be maintained as a foundation for its activities and to commence those activities or preparatory work based on this trust.

The Role of Good Faith and Equity

The Supreme Court then invoked a core legal principle to govern these relationships:

- Even if no formal contract explicitly obligating the local government to maintain the policy has been concluded, when parties have entered into such close negotiations and a relationship of reliance, the principle of good faith and equity (shingi kōhei no gensoku) must regulate their interactions.

- According to this principle, if the policy is changed, the trust placed by the private entity that acted upon the government's specific inducements must be afforded legal protection. The legal commentary highlights that the Supreme Court's derivation of legal protection from this broad principle, rather than solely from a strict interpretation of tort statutes, gives the ruling a "law-creating color".

Conditions for Tort Liability for Policy Change

The Court laid out specific conditions under which a local government could be held liable in tort for damages resulting from such a policy change:

- Specific Inducement and Reliance: The local government must have made individual, specific recommendations or inducements to the private party, motivating them to undertake activities that presuppose long-term policy continuity.

- Frustration of Activity and Affirmative Damages: The policy change must have thwarted the party's intended activities, which were undertaken in reliance on those inducements, causing them to suffer affirmative damages (sekkyokuteki songai – meaning actual, out-of-pocket losses or expenditures) to an extent that cannot be overlooked from a societal perspective. The judgment specifically refers to "affirmative damages," implying a focus on reliance damages (e.g., wasted investments) rather than necessarily lost profits or expectation damages.

- Lack of Compensatory Measures: The local government changes the policy without taking compensatory measures, such as indemnifying the party for the affirmative damages incurred.

- Absence of Unavoidable Objective Circumstances: The policy change is not due to unavoidable objective circumstances (yamu o enai kyakkanteki jijō).

If these conditions are met, the local government's action of changing the policy without providing compensation is considered an unlawful destruction of the trust relationship that had been formed, giving rise to tort liability.

Resident Autonomy is Not an Absolute Shield

The Supreme Court explicitly stated that the principle of resident autonomy does not imply that a local government bears no legal responsibility for its actions, even if those actions are based on the will of the residents. A mere change in the political climate or local leadership that formed the basis of the policy decision does not automatically qualify as "unavoidable objective circumstances" that would justify disregarding the trust placed by the relying party.

Application to Company X's Case

Applying these principles to the facts at hand, the Supreme Court found:

- The former mayor (A), acting with the village council's approval, had not only promised full cooperation but had also consistently and actively encouraged Company X's factory construction project for nearly two years. These actions constituted specific inducements.

- Company X, relying on these inducements, undertook significant steps such as securing and preparing the factory site and ordering machinery—actions that the village leadership had anticipated and indeed hoped for.

- The nature of constructing a paper mill inherently involves a plan for long-term operation and requires substantial capital investment.

- When the new village administration withdrew its cooperation, rendering the factory construction impossible at an early stage, if Company X consequently suffered substantial affirmative damages, then Y Village's refusal to cooperate would be deemed an illegal tortious act against Company X, unless this refusal was based on unavoidable objective circumstances or some form of compensatory measures were provided to offset X's losses.

Remand for Factual Determination

The Supreme Court concluded that the High Court had erred in its interpretation of the law when it rejected Company X's claim based on the argument that the village was free to change its policy without consequence. Therefore, the relevant part of the High Court's judgment was reversed, and the case was remanded (sent back) to the Fukuoka High Court, Naha Branch, for further proceedings. The High Court was instructed to examine:

- Whether Y Village's refusal to cooperate with the factory construction was, in fact, based on "unavoidable objective circumstances".

- The causal relationship between the village's refusal and the impossibility of Company X constructing or operating the factory.

- The nature and extent of the affirmative damages actually suffered by Company X.

Analysis and Implications

This 1981 Supreme Court decision is a landmark in Japanese administrative law, particularly concerning the protection of trust in government-business interactions:

- Establishing Protection of Trust: It was a groundbreaking ruling that clearly established that private entities could, under specific conditions, claim damages if a government entity reversed prior specific inducements that had led to substantial private investment.

- A Delicate Balancing Act: The judgment carefully attempts to balance two competing interests: the government's inherent need for policy flexibility to respond to democratic mandates and evolving societal needs, and the private sector's legitimate need for a degree of predictability and protection when relying on specific government representations and commitments.

- High Threshold for Compensation: While opening the door for such claims, the Supreme Court set a relatively high threshold. A claimant must demonstrate more than just a general policy announcement; there must be individual, specific inducements, reliance on long-term policy continuity for economic viability, the suffering of significant affirmative damages, and a lack of compensatory measures from the government or overriding unavoidable objective circumstances justifying the policy change.

- Focus on "Affirmative Damages": The Court's emphasis on compensating "affirmative damages" suggests a focus on restoring the actual out-of-pocket losses incurred by the relying party (reliance interest), rather than compensating for potential lost profits (expectation interest), which are often more speculative and harder to secure in such administrative law contexts.

- "Unavoidable Objective Circumstances": The precise scope of what constitutes "unavoidable objective circumstances" that might excuse a government from liability was left somewhat open by this decision, to be determined on a case-by-case basis. However, the Court did clarify that a simple change in local political leadership or a shift in resident sentiment, by itself, would not automatically suffice.

- Guidance for Government-Business Interactions: The decision offers crucial lessons for both public and private sector actors. Government entities must be mindful of the nature and specificity of the commitments and inducements they offer to businesses. Conversely, businesses need to carefully assess the nature of government assurances and the potential risks involved, though this case provides a basis for legal recourse when reliance on very specific inducements is unjustly frustrated.

- Theoretical Underpinnings: Legal scholars have discussed various theoretical bases for such liability, including principles analogous to culpa in contrahendo (fault in pre-contractual negotiations) or specific administrative law doctrines like "planning compensation liability" (keikaku tanpo sekinin) or loss compensation (sonshitsu hoshō). The Supreme Court, however, framed its reasoning primarily within tort law, predicated on a breach of the principle of good faith and equity that should govern the close relationship formed between the parties.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1981 ruling in the factory inducement case involving Company X and Y Village represents a significant development in Japanese law regarding the state's responsibility when its policy changes adversely affect private parties who have relied on specific prior inducements. While affirming the government's general right to alter its policies, the Court established that this power is not unfettered. Where specific, long-term reliance has been induced, leading to substantial affirmative loss due to a policy reversal made without unavoidable cause or adequate compensation, the principle of good faith and equity demands protection for the trusting party, potentially giving rise to tort liability for the government entity. This decision underscores the importance of trust and fair dealing as fundamental principles underpinning the relationship between the state and private actors in the economic sphere.