When Private Lives Become Public Interest: A Landmark Japanese Defamation Ruling

Where does the public's right to know end and an individual's right to privacy begin? Can a newspaper or magazine publish details about a person's private life, especially a sexual scandal, and defend it as a matter of "public interest"? This critical question, which stands at the intersection of freedom of the press and the protection of personal reputation, was the focus of a foundational ruling by the Supreme Court of Japan on April 16, 1981.

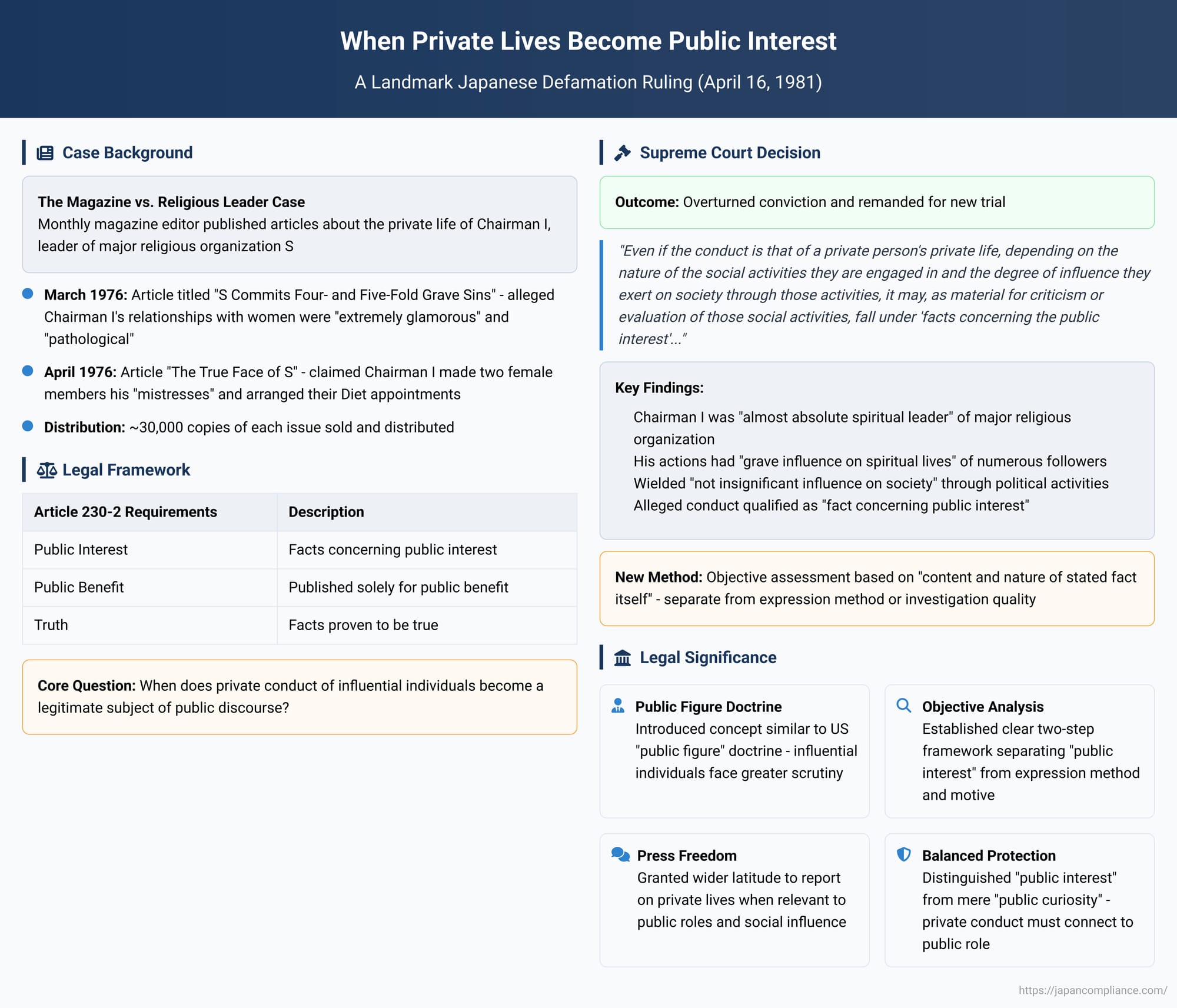

The case involved scathing allegations against the leader of a prominent and powerful religious organization. In its decision, the Supreme Court overturned the convictions of a magazine editor, establishing a landmark test for determining when the private conduct of influential individuals becomes a legitimate subject of public discourse and criticism. This ruling created a framework that continues to shape the balance between free speech and reputation in Japan today.

The Legal Framework: Exemption from Defamation in Japan

In Japan, the crime of defamation, defined in Article 230 of the Penal Code, can be established even if the statements made are true. However, Article 230-2 provides a crucial exemption to protect freedom of speech and the press. For a publisher to be immune from liability for defamation, three conditions must be met:

- The matter must concern facts of public interest.

- The act of publishing must have been done solely for the public benefit.

- The facts stated must be proven to be true.

If all three conditions are satisfied, the act is not punishable. This case centered on the first and most fundamental of these conditions: what qualifies as a "fact of public interest"? Unlike pre-war press laws, the modern Penal Code does not automatically exclude matters of a person's private conduct (shikō) from this category, leaving the door open for the courts to define its boundaries.

The Facts of the Case: The Magazine vs. The Religious Leader

The defendant was the editorial director of a monthly magazine that published a series of critical articles about a major Japanese religious organization, identified as S. As part of this critique, the magazine took aim at the private life of the organization's chairman, I, who was seen as its symbolic leader.

Two articles led to the defamation charges:

- The March 1976 Issue: Under the headline "S Commits Four- and Five-Fold Grave Sins," an article claimed there was "information from influential sources" that Chairman I's relationships with women were "extremely glamorous, and moreover, that the miscellaneous relationships were pathological and even nymphomaniacal".

- The April 1976 Issue: Under the headline "The True Face of S, Committer of Heinous Grave Sins," this article alleged that Chairman I had made two female members, T-ko and M-ko, his "mistresses" and had arranged for both to be sent to the National Diet (Japan's parliament) as members of the K political party.

Approximately 30,000 copies of each magazine issue were sold and distributed. The defendant was prosecuted for defaming Chairman I, the two women T-ko and M-ko, and the religious organization S. The defendant argued for his acquittal under Article 230-2, claiming the publications were in the public interest.

The Lower Courts' Verdict: Private Scandal is Not Public Interest

Both the Tokyo District Court and the Tokyo High Court found the defendant guilty of defamation. They rejected his defense, ruling that the articles did not concern facts of "public interest". Their reasoning was based on a comprehensive assessment of various factors. They noted that the articles detailed scandalous and private sexual misconduct, were written in an insulting and mocking tone, appeared to be based on uncertain rumors, and caused severe damage to the reputations of the individuals involved. Weighing these points, the lower courts concluded that the publications lacked the necessary public utility to qualify for the exemption under Article 230-2.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Reversal

The Supreme Court overturned the lower courts' convictions and remanded the case for a new trial. In its judgment, the Court established a new, authoritative principle for determining when private actions become a matter of public interest.

The Court acknowledged that the articles contained "scandalous matters of relationships with the opposite sex that one would generally hesitate to make public". However, it then articulated its groundbreaking test:

"Even if the conduct is that of a private person's private life, depending on the nature of the social activities they are engaged in and the degree of influence they exert on society through those activities, it may, as material for criticism or evaluation of those social activities, fall under 'facts concerning the public interest'..."

Applying this new principle to the facts, the Court found that Chairman I was far from an ordinary private citizen. He was the "almost absolute spiritual leader" of one of Japan's largest religious organizations, whose words and actions, both public and private, had a "grave influence on the spiritual lives" of his numerous followers. Furthermore, he wielded "not insignificant influence on society in general" through political activities connected to his religious status. The two women involved were also influential, having served as executives in the organization's women's division and as former members of the National Diet.

Given this context, the Court concluded that the alleged conduct of Chairman I and the others was not merely a "private affair within a religious group". Instead, it qualified as a "fact concerning the public interest" because it was relevant for evaluating the character and activities of a highly influential public figure and the organization he led.

A New, Clearer Method of Judgment

Beyond the core principle, the Supreme Court's decision was also revolutionary for the method it prescribed. The lower courts had conflated several issues, mixing the content of the allegations with the insulting tone of the articles and the poor quality of the investigation. The Supreme Court rejected this muddled "comprehensive judgment" approach.

It ruled that the question of whether a fact is of "public interest" must be judged objectively, based on the "content and nature of the stated fact itself". Other factors, such as the "method of expression" (e.g., insulting language) or the "degree of factual investigation," are not relevant to this specific question. Instead, those factors should be considered when assessing the other conditions of Article 230-2, such as whether the publisher's primary motive was for the "public benefit". This separation of concerns brought much-needed clarity and rigor to the legal analysis.

Implications: Public Figures and the Right to Know

This 1981 ruling is often seen as introducing a concept into Japanese law that is functionally similar to the "public figure" doctrine in United States jurisprudence. While the legal mechanics are different, the underlying principle is the same: individuals who occupy positions of significant social influence must accept a greater degree of public scrutiny, and the protection of their reputation may recede when their private actions are relevant to their public roles.

The decision grants the press and other commentators wider latitude to report on the private lives of powerful people, so long as the reporting serves as "material for criticism or evaluation of those social activities". However, this is not a license to publish any and all gossip. The court distinguishes between what is in the "public interest" and what is merely of "public curiosity". The private conduct must have a logical connection to the individual's public role and influence to be considered a matter of legitimate public concern.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1981 decision in the Gekkan Pen case was a watershed moment for Japanese defamation law. It courageously recognized that in a democratic society, the private lives of the powerful are not always off-limits. By establishing a clear two-step analytical framework—first objectively assessing the public interest nature of the topic, then separately considering factors like motive and truth—the Court created a sophisticated and durable test for balancing the fundamental right of free expression against the right of individuals to their reputation. The ruling affirmed that when a person's influence on society is immense, the public has a legitimate interest in knowing whether their private actions align with their public persona.