When Piety Meets Profit: Japanese Supreme Court on Taxing a Religious Corporation's Pet Funeral Business

Date of Judgment: September 12, 2008

Case Name: Corporate Tax Assessment Invalidation Lawsuit (平成18年(行ヒ)第177号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

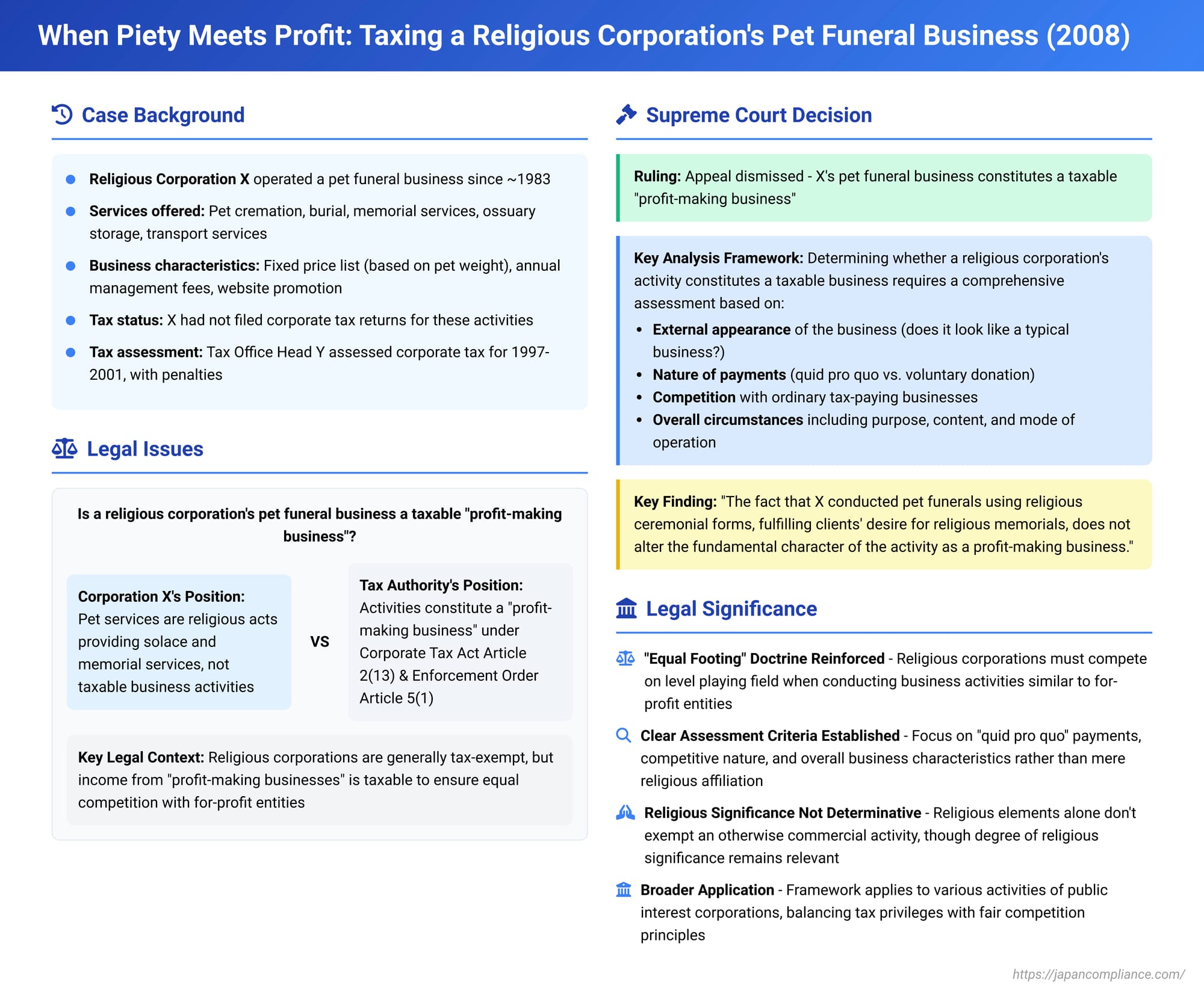

In a notable decision on September 12, 2008, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed the question of when services provided by a religious corporation cross the line from non-taxable religious activities into a "profit-making business" subject to corporate income tax. The case specifically concerned a pet funeral and memorial service operation run by a religious corporation, X, and provides significant guidance on how Japanese tax law views commercial-like activities undertaken by traditionally non-profit entities.

The Factual Landscape: A Religious Corporation's Pet Services

The appellant, X, was a religious corporation that, since around 1983 (Showa 58), had been conducting a business offering funerals, cremations, and memorial services for deceased pets. This "pet funeral business in question" was not a minor sideline; X had established dedicated facilities, including a crematorium and cemetery plots, on its grounds for this purpose.

The services offered by X were quite comprehensive:

- A price list detailed fees for pet funerals and cremations, which varied based on the pet's weight and the chosen type of cremation (e.g., communal, individual unattended, or individual attended).

- For clients opting for individual cremations, X offered interment in an ossuary or individual grave plots for an additional fee. These individual options also came with annual management fees, and a renewal fee was required after a certain period (e.g., at the third 3-year renewal, or 9th year). If these fees remained unpaid for three months or more, or if the usage period was not renewed, the pet's remains would be moved to a communal grave.

- X also sold related items such as tōba (wooden memorial tablets) and ihai (ancestral tablets).

- A paid service was available to transport the deceased pet's body to X's facility. The judgment details that a 3,000 yen fee was charged for this pick-up service.

- Furthermore, X conducted paid memorial services, such as those on the 7th and 49th days after a pet's death, for clients whose pets were interred at its facility.

- X actively promoted these services through brochures with photographs and by maintaining a website, detailing its operations under the name "X Animal Reien (Cemetery)". The price list itself was reportedly created by X's representative director by referencing a price list from a limited liability company engaged in a similar business.

Despite conducting this fairly extensive operation, X had not been filing corporate income tax returns. The head of the competent tax office, Y (the defendant), determined that X's pet funeral business constituted a "profit-making business" (shūeki jigyō) as defined under Article 2, item 13 of the Corporate Tax Act and Article 5, paragraph 1 of the Corporate Tax Act Enforcement Order (the version prior to the 2008 amendment, Order No. 156). Consequently, Y issued a corporate tax assessment for the fiscal years 1997 through 2001 (specifically, April 1, 1996, to March 31, 2001, covering five business years as per the judgment text, though the PDF facts section states Heisei 9-13 which is 1997-2001) and imposed penalties for non-filing.

X challenged this determination, arguing that its activities were essentially religious acts of providing solace and memorial services, and thus should not be subject to corporate income tax. The Nagoya District Court (March 24, 2005) and subsequently the Nagoya High Court (March 7, 2006) both ruled against X. The High Court notably stated that whether an act is religious in nature does not, by itself, immediately determine whether it qualifies as a profit-making business for tax purposes. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

Taxation of Religious Corporations in Japan

Under Japanese law, religious corporations like X are classified as a type of "public interest corporation, etc." (公益法人等 - kōeki hōjin tō). Generally, such corporations are subject to corporate income tax only on the income they derive from specifically enumerated "profit-making businesses". At the time of this case, there were 33 such business categories listed in the Corporate Tax Act Enforcement Order (currently 34). This limited taxation framework is designed, in part, to ensure that when non-profit entities engage in activities that could compete with regular for-profit businesses, they do so on a relatively level playing field regarding tax burdens. Additionally, religious corporations (and other specific domestic corporations listed in Schedule 1 of the Income Tax Act) are not liable for income tax that is typically collected through withholding (e.g., on certain types of income they might receive). Therefore, the scope of income taxation for a religious corporation hinges critically on how these "profit-making businesses" are defined and whether the corporation's activities fall within those definitions.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Defining a "Profit-Making Business"

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of September 12, 2008, dismissed X's appeal, affirming the lower courts' decisions that the pet funeral business was indeed a taxable profit-making business.

The Court laid out a clear analytical framework for this determination:

- External Appearance of the Business: The Court first noted that, viewed externally, X's pet funeral business exhibited the characteristics of business types typically considered profit-making, such as contracting, warehousing, and goods sales, along with ancillary activities related to these.

- Guiding Principle – Equal Footing and Tax Fairness: The Court emphasized the underlying rationale for taxing the profit-making activities of public interest corporations: "to ensure equal conditions of competition with other domestic corporations engaged in similar businesses and to secure fairness in taxation". This is often referred to by commentators as the "equal footing" doctrine (イコール・フッティング論 - ikōru futtingu ron).

- Comprehensive Criteria for Assessment: Based on this principle, the Court stated that determining whether a religious corporation's activity (which has the external form of a listed business like contracting) falls under the definition of a profit-making business requires a comprehensive examination of various factors, viewed through the lens of societal common sense (shakai tsūnen). These factors include:

- Nature of Monetary Transfers: Is the money received by the corporation a payment for services rendered (a quid pro quo), or is it in the nature of a voluntary donation or offering (kisha - 喜捨)?

- Competition: Does the activity compete with similar businesses operated by ordinary corporations that are fully subject to corporate income tax?

- Overall Circumstances: The purpose, content, and mode (manner of operation) of the activity in question.

Applying these criteria to X's pet funeral business, the Supreme Court found:

- Quid Pro Quo Established: X had established price lists, and clients paid fixed amounts for the services they received. This strongly indicated that the payments were consideration for services, not voluntary religious offerings, even if clients may have felt a religious significance in the transactions.

- Competition with Secular Businesses: The Court noted that pet memorial services had become widespread in Japan since the 1970s and 1980s, with numerous providers, including not only Buddhist temples but also warehousing companies, transport companies, real estate firms, stone masonry shops, and animal hospitals. X's business, in its purpose, content, pricing methods, and promotional activities (like its website and brochures), was not fundamentally different from these secular operations and inevitably competed with them.

- Religious Ceremony Does Not Negate Business Nature: Given the clear quid pro quo and the competitive nature of the services, the fact that X conducted the funerals using religious ceremonial forms, fulfilling the clients' desire for a religious memorial for their pets, did not alter the fundamental character of the activity as a profit-making business under the Corporate Tax Act Enforcement Order (specifically items 1 for contracting, 9 for warehousing, and 10 for sales of goods) and thus a "profit-making business" under Article 2, item 13 of the Corporate Tax Act.

The Role of "Religious Significance"

The Supreme Court's framework includes considering the "purpose, content, and mode" of the business, which implicitly allows for the consideration of its religious significance. However, legal commentary has noted that the Court, in this particular judgment, did not delve deeply into an analysis of the degree of religious significance of X's pet funeral services as perceived by society.

This is an important nuance because existing tax administrative practice in Japan (e.g., Corporate Tax Basic Circulars 15-1-10(1) and 15-1-72) often treats the sale of religious items like omamori (amulets), ofuda (talismans), omikuji (fortune slips), or fees for traditional Shinto or Buddhist wedding ceremonies as non-profit-making activities, even though they involve fixed charges (a quid pro quo) and may compete with secular services (e.g., commercial wedding halls). The prevailing understanding, as suggested by commentators, is that these traditional religious activities are deemed by societal common sense to possess such a high degree of inherent religious significance that this characteristic outweighs the commercial aspects, thus excluding them from the "profit-making business" category.

In X's case, the Supreme Court did not explicitly state that the pet funeral business lacked religious significance. However, as the first instance judgment noted, there were instances of similar pet funeral services being operated by for-profit entities, sometimes through religious corporations. This might suggest that, in the eyes of society and therefore the Court, X's pet funeral services, while having a religious component, did not carry the same profound and uniquely religious weight as, for example, the sale of sacred amulets at a historic temple or a traditional religious rite like marriage. One commentator, however, has argued that religious services conducted by religious corporations are inherently different from "religious business" conducted by for-profit entities.

Broader Implications: The "Equal Footing" Principle

The "equal footing" doctrine is the cornerstone of the Supreme Court's reasoning in this case and in the broader context of taxing income from public interest corporations. The logic is that if a non-profit entity engages in activities that directly compete with for-profit businesses, its income from such activities should be taxed to prevent an unfair competitive advantage that would arise from tax exemption.

The analytical criteria set forth by the Supreme Court in this pet funeral case—focusing on the nature of payment (quid pro quo vs. donation) and the existence of competition, alongside a general consideration of the activity's purpose, content, and mode—are seen as having broader applicability. These criteria are likely to be used in assessing whether various other activities undertaken by religious corporations or other types of public interest corporations constitute taxable profit-making businesses. The crucial question is how these factors, particularly the less defined element of "religious significance" as filtered through societal common sense, will be weighed in different contexts.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2008 decision in the pet funeral business case reinforces a pragmatic approach to the taxation of religious corporations in Japan. While acknowledging their special status, the Court made it clear that when such corporations engage in activities that bear the hallmarks of commercial enterprise—fixed fees for services and direct competition with secular businesses—those activities are likely to be deemed "profit-making businesses" subject to corporate income tax. The mere presence of religious ceremony or intent does not automatically shield such operations from taxation. This ruling underscores the importance of the "equal footing" principle in maintaining tax fairness within a mixed economy where non-profit and for-profit entities may offer similar services. The precise impact of an activity's "religious significance" as a countervailing factor remains an area where societal perceptions, as interpreted by the courts, will continue to play a vital, if somewhat nuanced, role.