When Love Ends: Understanding 'Nai'en' (De Facto Marriage) and Claims for Damages Upon Breakup in Japan - A 1958 Supreme Court Ruling

Date of Judgment: April 11, Showa 33 (1958)

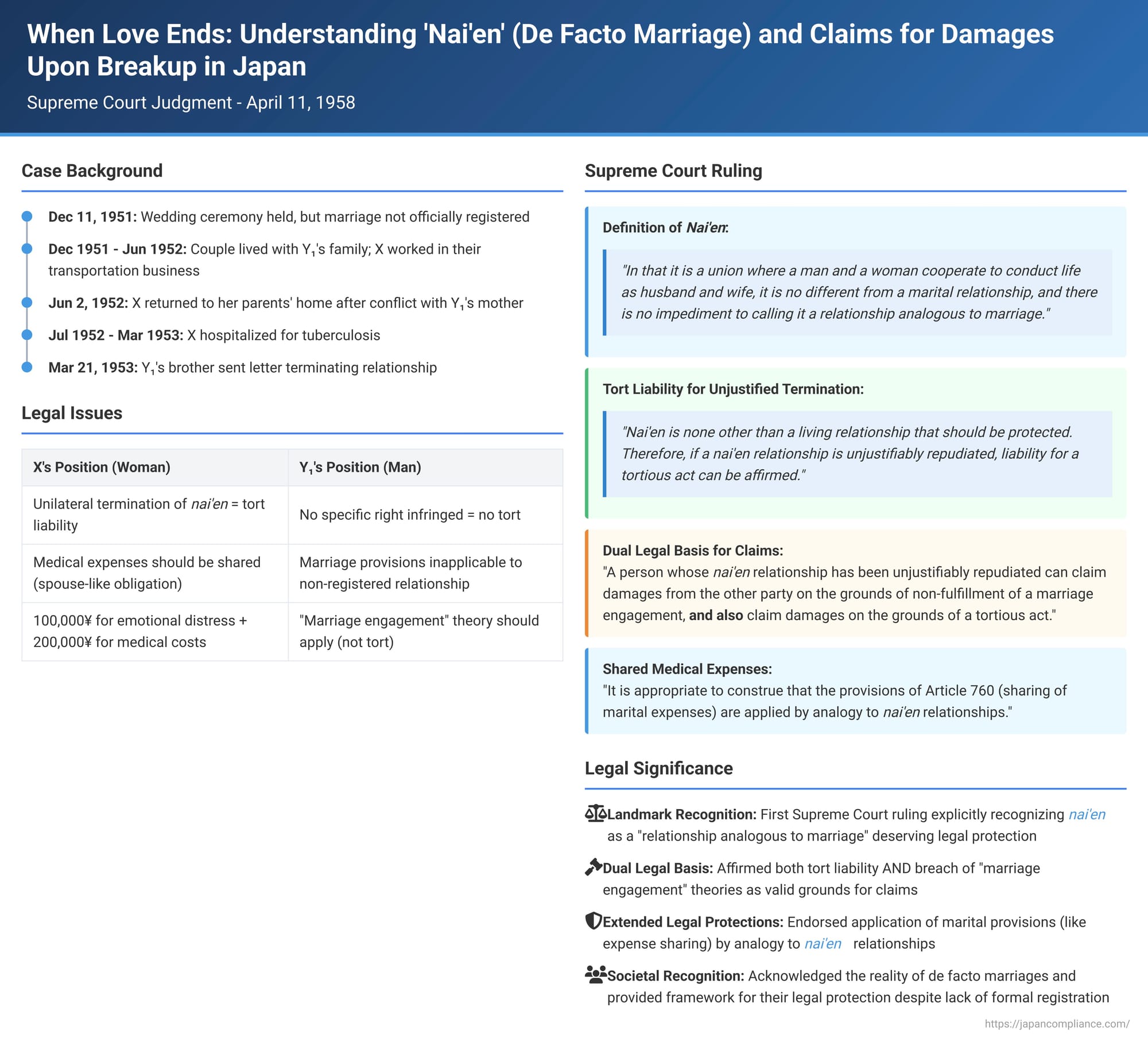

In Japan, while formal marriage requires official registration, many couples live together in relationships that are, for all intents and purposes, marital, but without having filed the necessary legal paperwork. These relationships are often referred to as nai'en (内縁), or de facto marriages. For a long time, the legal status and protections afforded to individuals in nai'en relationships, particularly upon their breakdown, were subjects of evolving judicial interpretation. A pivotal Supreme Court of Japan decision on April 11, 1958 (Showa 32 (O) No. 21) provided significant clarification, particularly regarding a partner's right to claim damages if the nai'en relationship is unilaterally and unjustifiably terminated by the other.

The Facts: A Relationship Formed, A Life Shared, and a Painful End

The case involved X (the woman) and Y₁ (the man). They held a wedding ceremony on December 11, 1951, and began living together at Y₁'s home with his parents and younger brother. However, they did not formally register their marriage. The Y₁ family ran a transportation business, and X worked diligently in this business from early morning until late at night, under the direction of Y₁'s mother, A.

Unfortunately, X's relationship with her mother-in-law, A, was fraught with difficulty. Y₁ consistently sided with his mother, leaving X feeling isolated within the household. On the night of June 2, 1952, after being scolded by A and criticized by Y₁ and others in the family, X contacted her father, B, asking him to come for her. Following discussions between B and Y₁'s family, it was agreed that X would return to her parental home for a period of rest and recuperation.

The day after returning to her parents' home, X developed a fever. A doctor diagnosed her with pulmonary tuberculosis. After consultation with Y₁ and his family, X continued her recuperation at her parents' home, which included a period of hospitalization from July 25, 1952, to March 1953. During this time, Y₁ and his mother, A, occasionally visited X.

However, on March 21, 1953, Y₁'s elder brother, C, sent X a registered letter demanding that she retrieve her belongings from Y₁'s house. This act effectively signaled the termination of X and Y₁'s relationship.

X subsequently filed a lawsuit against Y₁. She argued that Y₁ had unilaterally and unjustifiably broken off their nai'en relationship, causing her significant emotional distress. She sought 100,000 yen in solatium (damages for emotional suffering). Additionally, X claimed that Y₁ had a duty to share the medical expenses she had incurred for her tuberculosis treatment, which totaled over 314,000 yen, and sought 200,000 yen from him for this purpose, bringing her total claim to 300,000 yen.

The first instance court found in favor of X. It determined that the nai'en relationship between X and Y₁ had indeed been unilaterally terminated by Y₁ and that X had suffered immense emotional distress as a result. The court held Y₁ liable for this distress as a tortious act and ordered him to pay 100,000 yen in solatium. Furthermore, regarding the medical expenses, the court ruled that Civil Code Articles 752 (duty of spouses to cohabit, cooperate, and support each other) and 760 (sharing of marital expenses) should be applied by analogy to de facto marital relationships (nai'en). Therefore, it ordered Y₁ to bear 200,000 yen of X's medical costs.

The appellate court upheld the first instance judgment. Y₁ then appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing, among other points, that:

① For a tort to be established, there must be an illegal infringement of a right, which the lower court failed to specify.

② Precedent consistently applied "marriage engagement" theory to the unjust repudiation of nai'en relationships, treating it as a breach of contract, whereas the lower court incorrectly characterized it as a tort, thereby contravening established case law.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Affirming Tort Liability and Analogous Application of Marital Provisions

The Supreme Court dismissed Y₁'s appeal, upholding the lower courts' judgments in favor of X. The Court's reasoning provided crucial clarifications on the legal nature of nai'en and the remedies available upon its breakdown.

The Nature of Nai'en as a Legally Protected Relationship:

The Court began by defining nai'en: "So-called nai'en, because it lacks marriage registration, cannot be called a legal marriage. However, in that it is a union where a man and a woman cooperate to conduct life as husband and wife, it is no different from a marital relationship, and there is no impediment to calling it a relationship analogous to marriage (婚姻に準ずる関係 - kon'in ni junzuru kankei)."

Unjustified Termination of Nai'en as a Tort:

Addressing the core issue of liability, the Court stated: "And, while the 'rights' referred to in Article 709 of the Civil Code [the general provision for tort liability] need not be rights in the strictest sense, it is sufficient if there is an interest that should be legally protected... Nai'en is none other than a living relationship that should be protected. Therefore, if a nai'en relationship is unjustifiably repudiated, liability for a tortious act can be affirmed on the grounds that a right has been infringed intentionally or negligently."

Dual Basis for Claims: Tort and Breach of "Marriage Engagement":

Significantly, the Court did not limit the basis for a claim to tort law. It also acknowledged the pre-existing line of cases that had treated nai'en as a form of "marriage engagement" (kon'in yoyaku), allowing claims for breach of this engagement: "Thus, a person whose nai'en relationship has been unjustifiably repudiated can claim damages from the other party on the grounds of non-fulfillment of a marriage engagement, and can also claim damages on the grounds of a tortious act."

Analogous Application of Marital Expense Provisions to Nai'en:

Regarding X's claim for medical expenses, the Court reasoned: "Given that nai'en should be recognized as a relationship analogous to legal marriage as explained above, it is appropriate to construe that the provisions of Article 760 of the Civil Code [concerning the sharing of expenses arising from marriage] are applied by analogy to nai'en relationships. Therefore, the medical expenses incurred by X in this case, although arising during separation, should still be considered analogous to expenses arising from marriage, and Y₁ should bear a share of them in accordance with the purport of said article." The Court found the lower court's allocation of 200,000 yen to be borne by Y₁ as reasonable after considering all circumstances.

The Significance of the Ruling: Advancing the Legal Protection of De Facto Marriages

This 1958 Supreme Court decision marked a significant step forward in the legal recognition and protection of nai'en relationships in Japan. Its key contributions include:

- Affirmation of Tort Liability for Unjust Repudiation: This was a crucial development. While earlier case law, notably a Daishin'in decision from Taisho 4 (1915), had conceptualized nai'en as a "marriage engagement" and allowed damages for breach of this "contract," it had explicitly stated that such claims should be based on breach of contract, not tort. The 1958 Supreme Court ruling unequivocally opened the door to framing claims for unjust repudiation of nai'en as a tort, recognizing the infringement of a legally protected interest in the continuation of the de facto marital life.

- Continued Recognition of "Marriage Engagement" Theory for Nai'en: While endorsing the tort approach, the Court also explicitly stated that a claim based on non-fulfillment of a "marriage engagement" remained viable. This acknowledged the existing line of precedent while expanding the avenues for redress.

- Explicit Positioning of Nai'en as "Analogous to Marriage": The Court's clear statement that nai'en is a "relationship analogous to marriage" provided a stronger conceptual foundation for applying various marital provisions by analogy to de facto couples. This was a significant endorsement of the "quasi-marriage theory" (jun婚理論 - junkon riron) advocated by many legal scholars who argued that nai'en relationships, which often mirrored formal marriages in all but registration, deserved similar legal protections.

- Application of Marital Expense Sharing (Civil Code Art. 760) to Nai'en: The decision's confirmation that Article 760 (duty to share marital expenses) applies by analogy to nai'en relationships was a concrete example of extending marital protections. This meant that partners in a de facto marriage could be held responsible for sharing necessary living and medical expenses incurred during the relationship, even during periods of separation, provided the nai'en relationship itself was still considered ongoing at the time the expenses were incurred.

The Historical Context: From Non-Recognition to Quasi-Marital Status

Understanding the importance of this 1958 ruling requires a brief look at the historical legal treatment of nai'en in Japan.

- In the Meiji era, when the Civil Code was enacted (requiring official registration for marriage – Article 739), official registration was not always a familiar or immediately adopted practice for all segments of society. Furthermore, social customs (like trial periods before registration) or legal impediments under the old "family system" (ie seido) sometimes led to couples living in marriage-like unions without formal registration. These were termed nai'en.

- Initially, courts, adhering to the legislative emphasis on registered marriage, generally refused to grant any legal effect to nai'en relationships. An exception was occasionally made if the termination of a nai'en relationship also involved defamation, in which case damages for harm to reputation might be awarded.

- A significant shift occurred with the Daishin'in decision of Taisho 4 (January 26, 1915). This ruling conceptualized nai'en relationships as "marriage engagements" – contracts to marry in the future. It declared such engagements valid and held that if one party unjustifiably refused to proceed with the formal marriage, the other could claim damages for breach of this "engagement contract." This was a pivotal change, providing a legal avenue for redress.

- While this "marriage engagement" theory offered some protection, many legal scholars found it an artificial construct. They argued that couples in established nai'en relationships were not merely "engaged" but were already living as de facto spouses. This led to the development of the nai'en junkon riron (theory of nai'en as quasi-marriage), which advocated for applying marital law provisions by analogy to nai'en relationships to the extent possible, and for treating their unjust termination as a tort.

- Over time, case law began to evolve, with some decisions implicitly recognizing the quasi-marital nature of nai'en even before the 1958 Supreme Court ruling. Social legislation in areas like factory law and social security also started to treat nai'en partners similarly to legally married spouses for certain benefits.

Points of Discussion Arising from the Judgment

The 1958 Supreme Court decision, while a landmark, also presented some points for further legal discussion:

- Tort vs. Contractual Liability: By affirming both tortious liability and the possibility of a claim for breach of "marriage engagement" (a contractual concept), the judgment didn't definitively prioritize one over the other or clarify the exact relationship between them. This left open questions about when one basis might be more appropriate than the other, or if they could be pursued concurrently or alternatively. Legal commentary suggests that in practice, the distinction between these two theories for claiming damages upon the breakup of a nai'en relationship might not always be strictly maintained, with many subsequent cases focusing on the tortious aspect, especially when the relationship is clearly established as a nai'en rather than a mere engagement to marry in the future.

- Defining Nai'en for Legal Protection: The judgment describes nai'en as a "union where a man and a woman cooperate to conduct life as husband and wife." The crucial question then becomes what factual elements are necessary to meet this definition and qualify for quasi-marital protection. Factors like a wedding ceremony (as in this case), cohabitation, shared finances, public presentation as a couple, and the intention to marry are all relevant. Later case law has continued to grapple with drawing the line between a preparatory engagement (kon'yaku) and a substantive nai'en relationship, often focusing on the degree of shared life and mutual commitment. More recent discussions and even court decisions have also begun to consider whether similar protections could extend to same-sex couples who live in marriage-like relationships, though this 1958 ruling was framed within the traditional understanding of marriage.

- Scope of Analogous Application: While this judgment applied Article 760 (marital expenses) by analogy, it opened the door for considering the analogous application of other marital provisions to nai'en relationships. Subsequent case law has indeed expanded this, applying provisions related to spousal agency for daily household matters (Article 761) and principles of property ownership (Article 762) to nai'en couples, though generally excluding those rights strictly tied to formal registration, such as automatic inheritance rights as a legal spouse.

Conclusion: A Vital Step Towards Recognizing De Facto Marital Realities

The Supreme Court's decision of April 11, 1958, was a critical milestone in the legal protection of individuals in nai'en (de facto marriage) relationships in Japan. By explicitly recognizing nai'en as a "relationship analogous to marriage" deserving of legal protection and by affirming that its unjust repudiation could give rise to a tort claim for damages, the Court significantly strengthened the legal standing of such unions. Furthermore, its endorsement of the analogical application of provisions like Article 760 (sharing of marital expenses) demonstrated a willingness to look beyond mere legal formalities and address the substantive realities of couples living in committed, marriage-like partnerships. This judgment laid a vital foundation for the subsequent development of case law and academic theory concerning the rights and obligations of partners in nai'en relationships, contributing to a more equitable legal framework for diverse family forms in Japan.