When Justice is Denied: Enforceability of Fraudulently Obtained Judgments in Japan

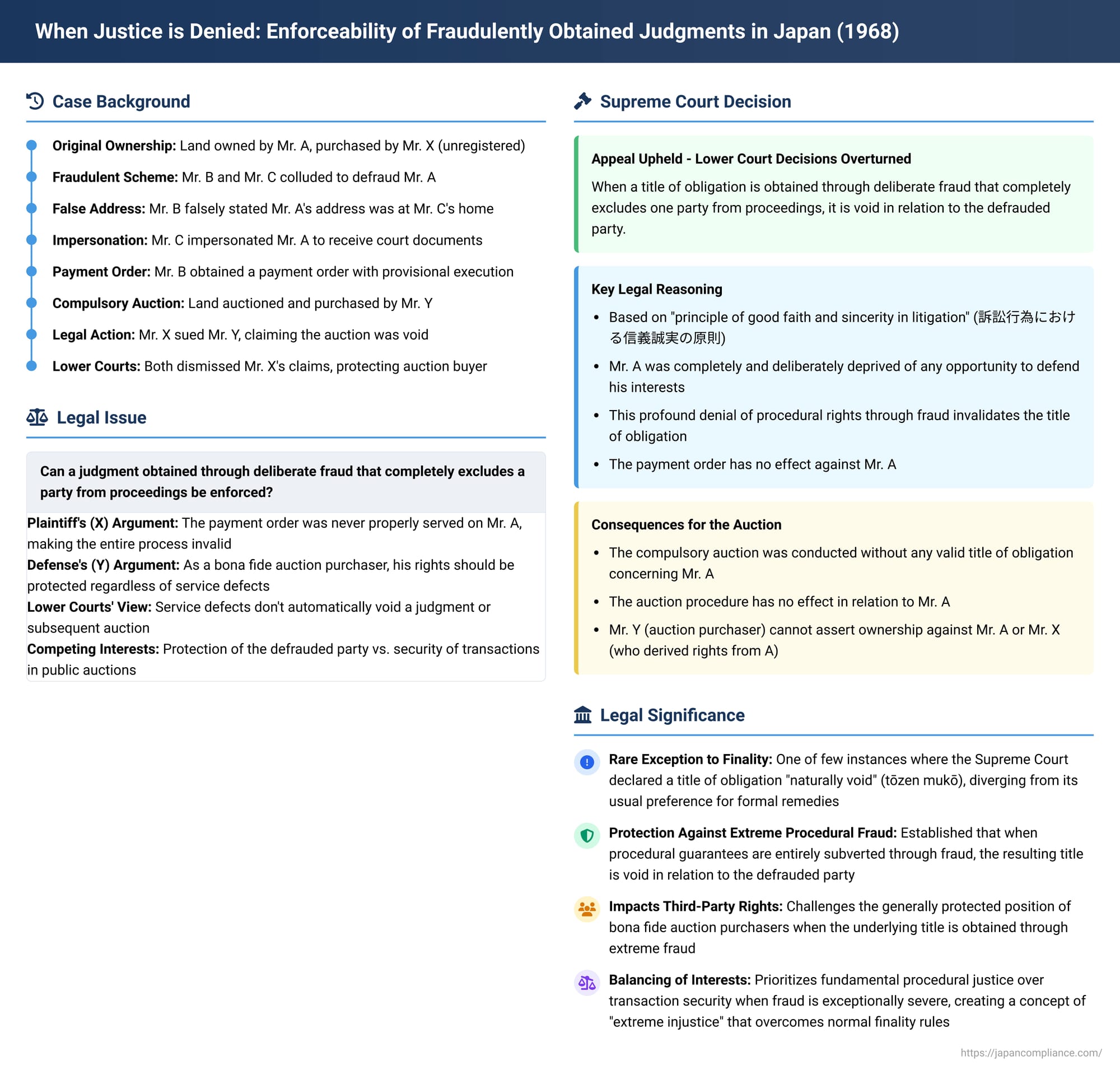

The integrity of the judicial process hinges on fundamental principles of fairness, including the right of all parties to be heard and to defend their interests. In Japan, a "title of obligation" (債務名義 - saimu meigi), such as a final judgment or a payment order with a declaration of provisional execution, is the cornerstone for initiating compulsory execution. But what happens when such a title is obtained not through due process, but through deliberate fraud that completely excludes one party from the proceedings? A landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on February 27, 1968, addressed this critical issue, establishing that a title of obligation procured under such egregious circumstances is void in relation to the defrauded party, rendering subsequent enforcement actions ineffective even against third-party purchasers.

Background of the Dispute

The case involved a parcel of land originally owned by Mr. A. The plaintiff, Mr. X, had purchased this land from Mr. A but had not completed the registration of the title transfer, leaving the land registered in Mr. A's name.

The central issue arose from the actions of Mr. B and Mr. C, who conspired to unlawfully profit from Mr. A's land. Mr. B, falsely claiming that Mr. A owed him money on a promissory note (the endorsement of which was actually forged), initiated legal proceedings against Mr. A. He applied for a payment order and subsequently a payment order with a declaration of provisional execution (a type of title of obligation allowing immediate enforcement).

Crucially, in these court applications, Mr. B deliberately provided a false address for Mr. A, stating Mr. A's residence as being at Mr. C's home. As a result, all court documents, including the payment order and the declaration of provisional execution, were "served" at Mr. C's address. Mr. C, acting in collusion with Mr. B, impersonated Mr. A and received these documents. Mr. A, the actual alleged debtor, remained completely unaware of these proceedings and was thus deprived of any opportunity to object or defend himself.

Armed with this fraudulently obtained payment order with provisional execution, Mr. B initiated compulsory auction proceedings against Mr. A's land. The notice of the auction commencement was also "served" at the false address (Mr. C's home). Subsequently, Mr. Y purchased the land at this auction and proceeded to build a house on it.

Mr. X (who had the unregistered prior claim from Mr. A) then filed a lawsuit against Mr. Y. Mr. X argued that the payment order used as the basis for the auction was not a valid title of obligation because it was never properly served on Mr. A. Therefore, X contended, the compulsory auction was void, and Mr. Y had not acquired valid ownership of the land. Mr. X sought confirmation of his (or A's underlying) ownership, cancellation of Mr. Y's registration, removal of Mr. Y's building, and recovery of the land.

The Maebashi District Court, the court of first instance, dismissed Mr. X's claims. It reasoned that (i) defects in the service of a title of obligation do not automatically render it void, and (ii) in the absence of evidence proving the non-existence of Mr. B’s underlying private law claim against Mr. A, Mr. Y was deemed to have validly acquired ownership through the auction.

Notably, after this first instance ruling, the payment order with provisional execution against Mr. A was retrospectively canceled in a retrial action initiated by Mr. A, and Mr. B's claim against Mr. A was definitively dismissed.

Despite this development, the Tokyo High Court also dismissed Mr. X's appeal. The High Court added that (i) the payment order was not automatically void even with the service defects, (ii) the auction procedure itself, having been conducted by a lawful enforcement agency and concluded without objection at the time, was also not automatically void, and Mr. Y acquired ownership unless the auction commencement decision was formally canceled, and (iii) even though the title of obligation was retroactively nullified by the retrial, this subsequent nullification did not invalidate the rights acquired by a third party (Mr. Y) through the already completed compulsory execution. Mr. X then appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court of Japan overturned the decisions of the lower courts and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Court laid down a crucial principle regarding titles of obligation obtained through such profound procedural fraud:

The Court reasoned that if a party (甲, representing B in this case) conspires with another (乙, representing C) to fraudulently obtain a title of obligation against a third person (丙, representing A) by:

- Falsely stating 丙's address as 乙's residence in court applications (e.g., for a payment order).

- Having the court issue these orders based on this false information.

- Having 乙 impersonate 丙 to receive all court documents, thereby preventing 丙 from making any objections and allowing the orders to become seemingly final.

In such a scenario, the Supreme Court declared that even if 甲 appears to have formally obtained a title of obligation against 丙, the effect of this title of obligation does not extend to 丙, and it is considered void in relation to 丙.

The Court's rationale was grounded in the principle of good faith and sincerity in litigation (訴訟行為における信義誠実の原則 - soshō kōi ni okeru shingi seijitsu no gensoku). It stated that 甲 and 乙, through their deliberate and collusive actions, intentionally concealed the existence of the legal proceedings from 丙. This conduct completely deprived 丙 of the opportunity to engage in any litigation activities or to take any measures to defend their interests. Such a profound denial of procedural rights, orchestrated through fraud, means that 甲 cannot assert the validity or effects of the obtained title of obligation against 丙.

The Supreme Court distinguished this situation from cases where a party might merely fail to participate in proceedings due to other reasons. Here, 丙 (A) was actively and entirely prevented from knowing about or responding to the actions of 甲 (B) and 乙 (C). Given this egregious reality, the Court found it impermissible to conclude that the effects of such a "judgment" could extend to 丙.

Applying this principle to the facts, since Mr. B had colluded with Mr. C to falsify Mr. A's address and had Mr. C impersonate Mr. A to receive court documents, the title of obligation (the payment order with provisional execution) obtained by Mr. B had no effect against Mr. A.

Consequently, if the title of obligation was void in relation to Mr. A, then the compulsory auction of Mr. A's land, which was conducted based on this void title, was effectively an auction carried out without any valid title of obligation concerning Mr. A. Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded, the compulsory auction procedure had no effect in relation to Mr. A, and the auction purchaser (Mr. Y) could not assert the acquisition of ownership against Mr. A (and by extension, against Mr. X, who derived his interest from Mr. A).

Significance and Analysis of the Decision

This 1968 Supreme Court judgment is a landmark decision in Japanese law, particularly for its clear stance on the invalidity of titles of obligation procured through extreme procedural fraud.

1. A Rare Instance of Declaring a Title of Obligation Void

The Supreme Court of Japan is generally very reluctant to declare final judgments or equivalent titles of obligation "naturally void" (tōzen mukō). Even in cases of judgments obtained through collusive lawsuits or based on perjured testimony or forged evidence, the Court often prefers remedies such as a retrial (再審 - saishin) or allowing a separate tort claim for damages against the defrauding party, while still upholding the formal validity (including res judicata and executory force) of the original judgment until it is formally overturned.

This case is remarkable because it deviates from that general trend. The key distinguishing factor was the total and deliberate deprivation of the defendant's (Mr. A's) opportunity to participate in the proceedings. Where procedural guarantees are not merely diminished but entirely subverted through fraud, the very legitimacy of the resulting title is destroyed.

2. The Basis of Invalidity: "Good Faith" vs. "Public Order"

The Supreme Court based its finding of invalidity (specifically, a "relative invalidity" concerning only Mr. A) on the violation of the "principle of good faith and sincerity in litigation". Some legal commentators have noted that while this principle is important for inter-party conduct, it might be a conceptually weaker basis for nullifying the inherent binding force of a court-issued title of obligation compared to, for example, a violation of "public order and good morals" (公序良俗 - kōjo ryōzoku), which has also been proposed as a standard in such cases.

3. Consequences for Compulsory Auction and the Rights of the Auction Purchaser

Generally, under Japanese law, if a compulsory auction is conducted based on a formally valid writ of execution, the title acquired by a bona fide auction purchaser is protected, even if the underlying claim is later found to be non-existent or the title of obligation is subsequently revoked (this is sometimes referred to as the "public trust effect of auction" - 競売の公信的効果 keibai no kōshinteki kōka). The lower courts in this case had initially followed this line of reasoning, protecting Mr. Y.

However, the Supreme Court took a different path. By finding the underlying title of obligation itself void in relation to Mr. A due to the egregious fraud, it reasoned that the auction lacked a fundamental legal basis concerning Mr. A's property. This led to the crucial conclusion that the auction purchaser, Mr. Y, did not acquire valid ownership that could be asserted against Mr. A (or Mr. X). This principle—that a compulsory auction based on a title of obligation deemed void due to such fundamental procedural deprivation does not transfer valid ownership to the purchaser as against the defrauded owner—has been upheld in subsequent Supreme Court jurisprudence, establishing it as a distinct legal doctrine.

This is importantly different from situations where a title of obligation is merely canceled through a retrial after the execution has been completed. In those cases, the auction purchaser's title is generally not affected. The concept of the title being "naturally void" from the outset, as in this case, provides a more direct path to relief for the defrauded party and affects the auction's outcome more profoundly.

4. Balancing the Interests of the Defrauded Party and the Bona Fide Auction Purchaser

The decision also implicitly involves a balancing of interests. Mr. Y, the auction purchaser, was ostensibly a bona fide third party who acquired the land through a seemingly valid public auction. Protecting the original owner (Mr. A, and by extension Mr. X) at the expense of such a purchaser requires the defect in the title of obligation to be exceptionally severe—an element of "extreme injustice" (kyōdo no futōsei). The commentary suggests that the extraordinary and fraudulent circumstances of this case, where Mr. A was completely and deliberately shut out from the legal process, justified prioritizing the protection of Mr. A and Mr. X over Mr. Y, despite Mr. Y's bona fide status.

5. Note on Payment Orders (Historical Context)

The PDF commentary mentions that the title of obligation in this case was a payment order with a declaration of provisional execution, obtained under the old Code of Civil Procedure. Under that old law, such payment orders, if unobjected to, could acquire the same effect as a final and binding judgment, including res judicata. The current Japanese Code of Civil Procedure has a different system for "demands for payment" (shiharai tokusoku), which, even if they become final, do not possess res judicata because they are typically issued by a court clerk rather than a judge after a full hearing. While this legal background of payment orders has changed, the core principle established by this 1968 Supreme Court case concerning titles of obligation obtained through the complete and fraudulent denial of procedural rights remains highly relevant.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1968 decision stands as a powerful affirmation that the Japanese legal system will not tolerate the enforcement of titles of obligation procured through schemes that fundamentally undermine procedural justice by entirely excluding a party from participation. When fraud is so egregious as to render the initial proceedings a complete sham in relation to one party, the resulting title of obligation is considered void concerning that party. This invalidity extends to nullifying subsequent compulsory execution procedures based on that title, even impacting the rights of third parties who may have purchased property at such an auction. This case underscores that the principle of finality of judgments must yield when the very foundation of due process has been deliberately and completely subverted.